Richard Wetz

Richard Wetz (born February 26, 1875 in Gliwice ( Upper Silesia ), † January 16, 1935 in Erfurt ) was a German composer , conductor , music teacher and music writer. His music is in a late romantic style and is based on the traditions of the 19th century, which Wetz tried to continue independently. He is considered to be the most important composer of the interwar period in Thuringia , has taught at the newly founded Thuringian Conservatory for Music in Erfurt since 1911 and was an outstanding teacher in the history of the Weimar University of Music from 1916 .

Life

1875–1906: youth and wandering years

Richard Wetz was born in 1875 as the son of the merchant Georg Wetz (1849–1903), who immigrated from Austria, and his wife Klara nee. Mucha (1852–1906) was born in Gleiwitz, Upper Silesia. He had a younger sister, Else (1877–1929), who later spent her life as a religious. Wetz's family owned a piano, but they weren't particularly interested in music. Thus, the young Richard, who was drawn to music at an early age, only received regular piano lessons at the age of eight, but soon tried himself out in composing smaller piano pieces and songs. According to his own statements, he made the decision to devote his life to music after hearing Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's “great G minor symphony” for the first time at the age of 13 .

After passing high school, Wetz went to Leipzig in 1897 to study at the local conservatory , among others with Carl Reinecke and Salomon Jadassohn . After only 6 weeks, however, he broke off his studies out of disappointment about what he thought was too academic lessons and preferred to take private lessons from the former director of the Leipzig Singing Academy , Richard Hofmann , and then from Alfred Apel, a student of Friedrich Kiel to be granted. At the same time he took up studies in philosophy , psychology and literature at Leipzig University . He immersed himself in the works of numerous poets: Friedrich Hölderlin , Heinrich von Kleist , Gottfried Keller , Wilhelm Raabe and especially Johann Wolfgang von Goethe achieved lasting importance for him. He also became a supporter of Arthur Schopenhauer's philosophical ideas . Richard Wetz left Leipzig in autumn 1899 and moved to Munich . There he began to study music one more time and, under the guidance of Ludwig Thuille , mainly practiced counterpoint and fugue .

As early as 1900, Wetz moved to Stralsund , where, with the support of Felix Weingartner, he was given a job as a theater conductor. A few months later he was in the same position in Barmen (today in Wuppertal ), and a short time later (without employment) back in Leipzig. Here he developed his own musical history by studying the scores of classical composers just as diligently as those of modern authors. Anton Bruckner and Franz Liszt were his most important guiding stars for the future .

1906–1935: Work in Erfurt and Weimar

In 1906 Richard Wetz was appointed head of the local music club in Erfurt . He soon found great pleasure in the city and lived there until the end of his life. Of his compositional work, Wetz had so far published almost exclusively piano songs , but had also tried the opera form twice . The composer himself wrote the libretto for the two works Judith op. 13 and Das Ewige Feuer op. 19 . The one-act play The Eternal Fire was performed in Hamburg and Düsseldorf in 1907 , both times with little success. However, Wetz achieved this even more a year later with his Kleist Overture Op. 16, which Arthur Nikisch conducted in Berlin .

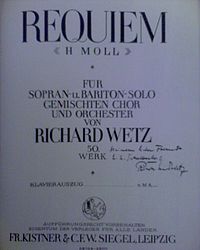

In the following years, in addition to his work in the music association and teaching at the Thuringian State Conservatory in Erfurt (1911–1921, composition and music history), Wetz devoted himself increasingly to conducting various choirs (in addition to the Erfurt Singakademie, in 1914/15 the Riedelschen Gesangverein in Leipzig and since 1918 also the Engelbrecht Madrigal Choir), as well as the composition of choral music, both a cappella and with orchestral accompaniment. Among these are especially the Gesang des Lebens, Op. 29, Hyperion, Op. 32 and a setting of the Third Psalm, Op. 37. However, they represent only the preliminary stage to his later major works: In 1917 Wetz completed his first symphony in C minor, op. 40. The symphonies No. 2 in A major, op. 47 and No. 3 in B minor, op. 48 followed in 1919 and 1922 At the same time, the composer was working on his two string quartets in F minor, Op. 43 and E minor, Op. 49. He then turned back to work on choral music, albeit larger-sized works than before: This is how the Requiem in B minor, Op 50 and the Christmas Oratorio on Old German Poems op. 53, his most important compositions. Wetz also became active as a music writer and wrote monographs on his revered role models Bruckner (1922) and Liszt (1925) as well as the equally highly esteemed Ludwig van Beethoven (1927).

Since October 1916, Wetz has taught music history, counterpoint, instrumentation and composition at the Grand Ducal Music School in Weimar, which is now the Liszt School of Music . In 1920 he was appointed professor there. The numerous students he taught over the years included a. Walter Rein , Werner Trenkner and Michael Schneider .

In October 1923 a four-day “Erfurt Music Festival” took place in Erfurt at the instigation of the large circle of friends of Wetz, at which only works by Wetz were heard, among others. a. his three symphonies. Although he resigned the official management of the Erfurt Musikverein in 1925, he continued to be the most respected figure in the city's musical life. In 1928, at the same time as Igor Stravinsky , Wetz was appointed an external member of the Prussian Academy of the Arts . A short time later he was offered a call to the Berlin Music Academy, which he, meanwhile advanced to one of the most successful composition teachers in Central Germany, turned down in favor of his offices in Erfurt and Weimar. In the 1930s, Wetz was increasingly drawn to work at the Weimar Academy of Music, which had an inhibiting effect on his compositional work. The last major composition he completed is the Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 57, finished in 1933. In the same year he was in discussion when it came to filling the vacant director of the university. Wetz's entry into the NSDAP , dated May 1, 1933, was probably based on the idea of increasing the likelihood of his appointment. However, Felix Oberborbeck was eventually preferred to him. There is no evidence of Wetz's active political activity in the NSDAP.

As part of the cooperation between the German Municipal Association and the Reich Chamber of Music, the city of Erfurt appointed him music commissioner in 1934. In October of that year, Wetz was diagnosed with lung cancer, probably a result of excessive smoking. His last work, the oratorio Love, Life, Eternity, based on texts by Goethe, with which he wanted to commemorate his favorite poet, remained unfinished. Richard Wetz died on January 16, 1935 in Erfurt, not yet 60 years old. His composition student Werner Trenkner declared himself ready to complete the well-developed sketches of the Goethe oratorio, but failed due to the objection of the estate administrator. Only the textbook of the work remained, while the music is considered lost.

Richard Wetz was not married. His grave is in the main cemetery in Erfurt .

reception

Wetz spent most of his life in Erfurt and did not intend to work in one of the great music metropolises, which might have promoted his career as a composer and conductor. Nevertheless, in the 1920s it gradually achieved nationwide recognition, which u. a. also reflected in the appointment as a member of the Prussian Academy of the Arts. He was well appreciated in professional circles, but never achieved the level of fame of Richard Strauss or Hans Pfitzner in the music world . In 1932 he commented on the performance situation of his compositions as follows: “My music is doing strangely: wherever it sounds it is deeply moving; but she is rarely given the opportunity to do so. "

The most important interpreter of Wetz's works was the conductor Peter Raabe , who had premiered all of the composer's symphonies and was appointed chairman of the Reichsmusikkammer shortly after his death in 1935 . Due to its late romantic, conservative style, which did not run counter to the officially desired art ideas, Wetz's music was also held in high regard in the Nazi state . In 1943 Raabe founded a Richard Wetz Society in Gleiwitz, but its activities were severely restricted by the Second World War . In the post-war period, Wetz, like many aesthetically similar composers, was relatively quickly forgotten because the priorities of musical life were now more modern styles.

Up until the 1990s, there were short entries on Richard Wetz in some concert guides, in which the high quality of his compositions was emphasized. Ceremonial events in his honor also took place occasionally, especially in Erfurt and at the Weimar Academy of Music. Overall, however, Wetz sank to a footnote in music history. It is only recently that people have started to become more aware of his work again, which is also reflected in CD recordings. Conductors who made a special contribution to Wetz are Roland Bader , Werner Andreas Albert and George Alexander Albrecht . Erfurt can still be regarded as the center of Wetz care, where several of his works have meanwhile been heard in concerts, including the Requiem in 2003 and the Christmas Oratorio in 2007 and 2010.

In 1994 the classical label cpo , which specializes in classical music first recordings, recorded its first symphony (Krakauer Philharmonie, Roland Bader), in 1999 its second (Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz, Werner Andreas Albert) and in 2001 its third.

style

Composer on the sidelines

If you look at Richard Wetz's life, it is not surprising that as early as 1929 “ Riemanns Musiklexikon” mentions him as “a loner who is not easy to classify”. He had relatively little contact with other composers and new achievements of his contemporaries, such as Arnold Schönberg , Maurice Ravel or Franz Schreker , either left him completely cold or drove those who were increasingly absorbed by cultural pessimism to polemic against it, sometimes quite violently. Most closely related to Wetz in his intellectual attitude were other keepers of the traditions of the 19th century, such as Hans Pfitzner and Siegmund von Hausegger , with whom he also shared his national German attitude. He also said he had to rely on familiar surroundings when composing: “ I can only compose at home. Neither in a summer vacation nor during longer visits have I ever created anything ”; says the composer about himself. Statements like these explain, for example, why Wetz only began to devote himself more to composing symphonies and larger choral works after the end of his years of traveling in Erfurt, but also why he later turned down all offers for more lucrative jobs.

Compositional development

The isolation from the mainstream of German musical life at the time allowed Wetz to concentrate fully on developing his own personal style:

As already mentioned, the composer wrote almost only songs in his early days. Even in later years of life he remained loyal to this genre, albeit in a quantitatively more limited form, so that by far the largest part of his work is song compositions. Thus Wetz can be considered one of the most important song masters of his generation. Relevant works by Franz Schubert , Liszt, Peter Cornelius and Hugo Wolf were decisive for him in this area . In addition to the songs, he also tried several orchestral works, of which he only accepted the Kleist Overture , a work inspired by the tragic fate of the poet, whom he admired. It later became his most played composition. The composer's first creative period culminated in his two operas, Judith and Das Ewige Feuer , which were influenced by Richard Wagner in their symphonic conception but had little impact on the stage , the first of which was never performed. Wetz broke off work on his third opera, Savitri , which, characteristically, he intended to temporarily turn it into an oratorio, in 1907 after three scenes. After that he did not return to music-dramatic composition.

The focus of work shifted to choral music at the beginning of the Erfurt years. Up until the First World War, only one sonata for violin solo was created among instrumental works. Inspired by Bruckner's sense of clear form structures and organic growth in the music as well as Liszt's harmonic innovations, Wetz's tonal language went through a consolidation process, the preliminary result of which was the symphonies, which were composed relatively quickly one after the other. They confirm a sentence that the composer communicated in a letter as early as 1897: "The old and the new direction fight tremendously in me, the old one will win." So it is not surprising that all three works are more conservative in the late Romantic symphony type then cultivated Embossing correspond. However, in their expression they show a pronounced individual personality, which Wetz does not appear as an epigone, but as an independent heir in dealing with tradition. Although powerful outbursts and humorous twists are not shied away from, a rather introverted mood dominates for a long time. They also provide clues for Wetz's isolation from the rest of the music business: For example, the first symphony ends in the initial key of C minor without (as Bruckner did) dissolving into a light major; an idea that was not exactly typical for the zeitgeist of the time. Overall, the two string quartets are very close to the symphonies, but already point beyond them with their more economical use of compositional means.

In later works Richard Wetz refined his style increasingly. Chromatic harmonies now find their way into his tonal language to an even greater extent, which in places no longer clearly adhere to the boundaries of tonality. Overall, there is also a greater turn to polyphony and the associated greater condensation of the movement, most pronounced in the organ piece Passacaglia and Fugue op. 55 from 1930. In his masterpieces, the Requiem and the Christmas Oratorio , Wetz succeeds in an excellent synthesis Symphonic and vocal music, in which he exaggerates the experiences he has gained. The one-movement violin concerto, which is unique in the composer's oeuvre in its free form, reminiscent of Liszt, seems, similar to the string quartets, to transition seamlessly into a new creative period, but it was never to be fully developed.

Illness and death caused the further development of the composer Richard Wetz to be interrupted prematurely, nevertheless he remains "one of the great and unmistakable talents of the German late romanticism" (Reinhold Sietz in Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart , 1968).

Works (selection)

Richard Wetz's catalog raisonné includes 58 opus numbers. In addition there are a small number of compositions published without numbering. Op. 1–4 and op. 6 are no longer traceable; the composer later declared some other early works with opus numbers to be invalid.

Operas

- Judith op.13 (1903, 3 acts; libretto: Richard Wetz)

- The Eternal Fire op.19 (1904, 1 act; libretto: Richard Wetz)

- Savitri (1907, unfinished; libretto: Richard Wetz)

Choral works

-

Dream Summer Night op.14 for women's choir and orchestra (1904)

(recording: Chamber Choir of the Augsburg University of Music, State Philharmonic of Rhineland-Palatinate, Werner Andreas Albert , 2004, cpo ) -

Gesang des Lebens op.29 for boys' choir and orchestra (1908)

(recording: State Philharmonic and State Youth Choir Rhineland-Palatinate, Werner Andreas Albert, 2001, cpo) - Choral song from Oedipus on Colonos "Not born is the best" op. 31 for mixed choir and orchestra (after Sophocles , 1901)

-

Hyperion op.32 for baritone, mixed choir and orchestra (based on Hölderlin , 1912)

(Recording: Markus Köhler, Chamber Choir of the Augsburg University of Music, State Philharmonic of Rhineland-Palatinate, Werner Andreas Albert, 2004, cpo) - The Third Psalm op.37 for baritone, mixed choir and orchestra (1914)

- Four sacred chants (Kyrie, Et incarnatus est, Crucifixus, Agnus Dei) for mixed choir a cappella op.44 (1918)

- Four old German sacred poems for mixed choir a cappella op.46 (1924), including:

- Kreuzfahrerlied op. 46/4 (after Hartmann von Aue in New High German poetry by Will Vesper .)

- Requiem in B minor op.50 for soprano, baritone, mixed choir and orchestra (1927)

(recording: Marietta Zumbält, Mario Hoff, Dombergchor Erfurt, Philharmonischer Chor Weimar, Thuringian Chamber Orchestra Weimar, George Alexander Albrecht, 2003, cpo) - Nacht und Morgen , song cycle for mixed choir a cappella op.51 (after Eichendorff , 1926)

-

A Christmas Oratorio on Old German Poems op.53 for soprano, baritone, mixed choir and orchestra (1929)

(recording: Marietta Zumbält, Máté Sólyom-Nagy, Dombergchor Erfurt, Philharmonic Choir Erfurt , Thuringian State Orchestra Weimar, George Alexander Albrecht, 2011, cpo) - Love, life, eternity , unfinished oratorio (after Goethe , lost)

Orchestral works

-

Kleist Overture in D minor, Op. 16 (1903)

(Recording: State Philharmonic Rhineland-Palatinate, Werner Andreas Albert, 1999, cpo) - Symphony No. 1 in C minor, Op. 40 (1916)

(recording: Philharmonic Orchestra Krakau, Roland Bader, 1994, cpo) -

Symphony No. 2 in A major op.47 (1920)

(Recording: State Philharmonic of Rhineland-Palatinate, Werner Andreas Albert, 1999, cpo) - Symphony No. 3 in B flat minor op. 48 (1922, notated in B flat major and referred to by the composer as " B flat major symphony ")

(recording: Berlin SO, Erich Peter, 1981, Sterling)

(recording: Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland- Pfalz, Werner Andreas Albert, 2001, cpo) -

Violin Concerto in B minor, Op. 57 (1932)

(recording: Ulf Wallin (violin), State Philharmonic of Rhineland-Palatinate, Werner Andreas Albert, 2004, cpo)

Chamber music

- Sonata for solo violin in G major op.33 (1911)

- String Quartet No. 1 in F minor op.43 (1916)

(recording as part of the International Music Score Library Project by Steve Jones via playback, 2011) - String Quartet No. 2 in E minor, Op. 49 (1923)

(Recording: "String Quartets of the 20th Century", Mannheim String Quartet, 1995, MDG )

Organ music

- Passacaglia and Fugue in D minor op. 55 (1930)

(recording: "Wake up, call us the voice", Silvius von Kessel plays symphonic organ music, 2000, motet)

(recording: "Orgelland Niederlausitz Vol.1", Lothar Knappe, 2003, H'ART) - Little Toccata in E minor (1918)

Piano music

- Romantic variations on a theme of their own, op.42 (1916)

- Five Piano Pieces op.54 (1929)

Songs

- approx. 100 piano songs (mostly composed between 1897 and 1918), including:

- Six songs for medium voice and piano op.5

- Five chants for medium voice and piano op.9

- Five songs for a high voice and piano op.10

- Five chants for medium voice and piano op.20

- Three poems by Ernst Ludwig Schellenberg for voice and piano op.30

- Two chants for medium voice and small orchestra op.52 (1926)

Fonts

- Anton Bruckner. His life and work , 1922

- Franz Liszt , 1925

- Beethoven. The spiritual foundations of his work , 1927

Honors

- “Wetzstraße” in Erfurt: so named in the year Wetz died in 1935

- "Richard-Wetz-Saal" at Domstrasse 9 in Erfurt: 2005 so named. Rehearsal hall of the Erfurt Cathedral Choir

- "German Richard Wetz Society", founded in 1948

literature

- George Armin: The songs of Richard Wetz , Leipzig 1911. - Short brochure.

- Ernst Ludwig Schellenberg: Richard Wetz , Leipzig 1911. - Short brochure.

- Hans Polack: Richard Wetz. His work and the intellectual foundations of his work , Leipzig 1935. - Monograph with detailed work analyzes, written by one of the composer's pupils.

- Erich Peter (Ed.), With collabor. v. Alfons Perlick : Richard Wetz as man and artist of his time (= publication by the Research Center for East Central Europe; A 28), Dortmund 1975. - Extensive, illustrated collection of sources with reports from contemporary witnesses and personal testimonies.

- Helmut Loos: Richard Wetz, a German symphonist . In: Music history between Eastern and Western Europe. Symphonics - music collections. Conference report Chemnitz 1995 , ed. by Helmut Loos (= German Music in the East 10). Sankt Augustin 1997, pp. 135-145.

- Erik Levy: Richard Wetz (1875-1935): a Brucknerian composer . In: Crawford Howie, Paul Hawkshaw and Timothy Jackson, Farnham et al. a. (Ed.): Perspectives on Anton Bruckner . 2001, pp. 363-394.

- Wolfram Huschke: Future Music. A history of the Liszt School of Music Weimar . Weimar 2006. - Wetz's activity as a composition teacher is mentioned in detail.

- Rudolf Benl (ed.): Richard Wetz (1875–1935). A composer from Erfurt (= Publications of the Erfurt City Archives 3), Erfurt 2010. - Anthology with contributions to life and work, letters from Wetz, as well as an overview of archival sources.

Web links

- Works by and about Richard Wetz in the catalog of the German National Library

- Sheet music and audio files by Richard Wetz in the International Music Score Library Project

- Digitization of a manuscript of the Five Piano Pieces op. 54 brahms-institut.de

- Brief introduction of the composer with pictures and catalog raisonné klassika.info

- Hans-J. Winterhoff: Wetz, Richard . In: East German Biography (Kulturportal West-Ost)

- Eric Schissel: Richard Wetz as composer . musicweb.uk.net (English)

- Brief introduction to Richard Wetz erfurt.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ jpc.de

- ↑ jpc.de

- ↑ jpc.de

- ^ Hartmann von Aue: songs. Poor Heinrich. New German by Will Vesper (= statues of German culture. Volume II). CH Beck, Munich 1906, p. 16 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Wetz, Richard |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German composer, conductor and music teacher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 26, 1875 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Gliwice , Silesia |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 16, 1935 |

| Place of death | Erfurt |