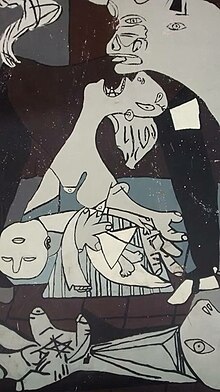

Guernica (picture)

| Guernica |

|---|

| Pablo Picasso , 1937 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 349 × 777 cm |

|

Reina Sofía Museum

Link to the picture |

Together with Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, Guernica is one of Pablo Picasso's most famous paintings . It was created in 1937 as a reaction to the destruction of the Spanish city of Guernica (Basque Gernika ) by the air raid by the German Condor Legion and the Italian Corpo Troop Volontarie , who fought on the side of Francisco Franco during the Spanish Civil War . On July 12, 1937, the picture was presented for the first time in Paris at the World's Fair . Today it is in the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid , along with an extensive collection of sketches .

Story of the picture

The destruction of Gernika

Gernika , the holy city of the Basques, is located east of Bilbao in northern Spain. She became known worldwide when she was attacked on April 26, 1937 by aircraft belonging to the German Condor Legion and the Italian Corpo Troop Volontarie during the Spanish Civil War . Gernika was part of the so-called "iron belt" around Bilbao and was bombed during the Spanish national offensive. After two more days, Spanish national troops from General Aranda marched into Gernika. The Spanish historian Julio Gil of Uned University describes the attack as follows:

“Gernika was one of the first bombings aimed at wiping out the civilian population. There the German Air Force tried the large-scale bombing that it would later use in Poland. Something like that was not known from the First World War . So Gernika was a turning point in the strategic importance of terrorizing the civilian population. "

Picasso's motivation

Picasso commented on his artistic stance as follows:

“It is my wish to remind you that I have always been and still am convinced that an artist who lives and treats spiritual values in the face of a conflict in which the highest values of humanity and civilization arise are at stake, cannot be indifferent. "

As early as 1936 Picasso was commissioned by the Spanish government to paint a picture for the Spanish pavilion at the 1937 World's Fair in Paris. After the attack on Gernika, he rejected his original idea of painting and model .

Since 1900 he was in connection with the left-liberal, anti-clerical and anarchic artist and literary group Els Quatre Gats in Barcelona . In Paris he made friends with the communist Paul Éluard . In addition, through his girlfriend Dora Maar and artists from the Parisian surrealist circle, he kept in touch with other politically active intellectuals, such as the writers André Breton and Louis Aragon . The legitimate government had launched important reforms. These included, for example, the land reform, the expansion of the educational network with public schools and a general liberalization of public and private life. Picasso was a staunch supporter of the Popular Front and its policies.

From 1936 until the end of the war he worked at 7 rue des Grands-Augustins. The studio in which Guernica was created also became his apartment from 1939. Honoré de Balzac already stayed in the former Hôtel de Savoie and the surrealists' meeting places were in the neighborhood.

Remaining of the picture after 1937

After the end of the Paris World Exhibition, the painting went on an extensive journey through Northern Europe and the USA. Oslo, Stockholm, Copenhagen, London, Leeds, Liverpool and New York were the stops where the painting was supposed to advertise the Republican side in the civil war. Picasso donated the income from the entrance fees to a foundation for the victims of the civil war. Since Picasso bequeathed the picture to a future Spanish republic, Guernica was exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art in New York from 1939 to 1981 . For many years Guernica hung there next to Max Beckmann's triptych Departure from 1932/1933 , an early vision of the approaching fascism. After Franco's death and the re-establishment of democracy in Spain, the image was brought to Spain in 1981 despite the reintroduction of the monarchy. It first came to the Prado in Madrid and has been in the Museo Reina Sofía , also in Madrid , since 1992 . It may no longer be borrowed in order to avoid irreparable damage.

Image composition and stylistic devices

Composition of the picture

The composition of the picture turned out to be extremely difficult. The colossal dimensions of 349 × 777 cm were determined by the architectural space when the pavilion was planned. In total, Picasso had to work on an area of more than 27 square meters. Another difficulty was the ratio of the horizontal to the vertical: the width is more than twice the height. Such a relationship is particularly suitable for a series of upright motifs, while Picasso wanted to create a scene of destruction with collapsing forms and lying figures.

To solve the difficulties, Picasso resorted to means of representation that he had already tried out in earlier times. Statements about the process of creation of the work, which is lengthy by Picasso's standards and associated with considerable compositional changes, as well as the significance of individual motifs can be made primarily because of the 46 individual studies that have been preserved and the photographic documentation by Dora Maar, eight in the period from May 11 to June 4th shows the conditions that have arisen. In order to understand the self-reflective content, the preliminary project discovered by Werner Spies is important , which refers to a studio scene “painter and model” as a starting point, the elements and structures of which (especially the triangle) can still be found in the final version.

Means of Christian art

Only when the work began on the canvas did motifs appear that were based on the Christian passion iconography . Presumably the exhibition of Catalan art from the 10th to 15th centuries in the Musée du Jeu de Paume , which he helped to prepare, sparked Picasso's interest in Christian art . An influence of the Isenheim Altarpiece by Grünewald , with which Picasso can be shown to have dealt with during this time, can also be assumed.

The following features of the picture allow an assignment to Christian painting: To break the frieze-like length of the picture, Picasso divided the picture into three parts, like a triptych (altar panels). This resulted in two side wings and a larger central field with the main motif, which often shows the crucified on altars. At this point, Picasso brought in a pyramidal scene of destruction, which in some interpretations is associated with an ancient gable, from his own iconography, a symbol of absolute suffering: the dying horse (mare). Above the horse, the ceiling lamp functions as the Eye of God or the Eye of Providence .

The horse's lancet-like wound bores into the animal's body, which has been split into fragments. By using the horse of the Corrida as a passion metaphor, a so-called sacrilization (sanctification) of the profane arose. Originally, Picasso had intended the dying warrior to replace the crucified one. Only fragments of the actual figure remained, which are lined up horizontally next to each other in the lower part of the picture, similar to a relic . In some interpretations, the extremely stretched arms are interpreted as a predella motif, they form the base of the winged altar.

Outside of the pyramidal construction with the dominant main motif, further motifs echoing Christian forms of representation are subordinate to the hierarchy on the side wings. On the left side wing, the crying mother with the dead child recalls the old Christian motif of the Pietà , Mary mourning the dead son. On the right side wing, seven flames symbolize the conflagration that stretched over Guernica at that time. In Christianity , the number seven stands for the apocalypse .

Means of cubism

Similar to the means of Christian iconography, in the history of the development of the picture, the elements from Cubism only appeared in the final stages of the canvas. Before that, the composition had a very linear character. With the clarification of the composition, a cubist plan with light and dark values became more and more popular. The strongest contrast of these values runs exactly through the center of the picture. While on the left of this border the scene with horse, pietà and bull is kept in dark gray tones, the right half with the fire scene and the light bearer in contrast literally shines.

Furthermore, the collage-like pattern of the faceted body of the main motif is an indication that Picasso consciously made use of the means of Cubism. From reports of studio visits we know that he had experimented with collages several times during the creation of the picture, for example the horse's body was covered with newspaper pages in the meantime. The bull and horse figures in particular are strongly reminiscent of Picasso's cubist phase, as they appear to be composed of different side views.

Color or grisaille

In the stairs of the Spanish pavilion was a monumental painting by another famous Spanish painter: Le Faucheur (The Reaper or Catalan Peasant) by Joan Miró , which has no longer survived. In his original concept, Picasso envisaged a color representation of Guernica on a scale similar to that of Miró. Friends advised against it when they visited the studio.

One reason for using grisaille , i.e. a technique that uses only graduated shades of gray instead of colors, could be that Picasso wanted to match his painting with the photo documentation of victims of the civil war with their black and white photos, which was exhibited on the second floor of the pavilion . Picasso admired the film Battleship Potemkin by the Russian director Sergei Eisenstein and, like him, wanted to show the devastation, the fear, and death in black and white in his Guernica . Another reason could be that he wanted to set a counterpoint to the concept of the world exhibition with his gloomy picture, because against all signs of the times, the exhibition area was integrated into fantastic light compositions and suggested a happy, peaceful, colorful world.

The architectural context

Josep Lluís Sert , a former Le Corbusier employee , and Luis Lacasa had planned Picasso's Guernica for the most visible place when they planned the Spanish pavilion . Picasso then developed his concept for the painting in close consultation with the architects. Space and image were closely coordinated. Often part of the effect of the picture was lost in other exhibitions because this aspect was not given enough attention.

The visitor entered the pavilion through an entrance to the right of the picture and passed it at a distance of about four meters to get into the large main hall. Contrary to the usual western way of reading a picture from left to right, Picasso therefore placed the reading direction of the picture from right to left so that the visitor path and the figure path could run synchronously.

He also included architectural features of the exhibition space, such as the tile motif and the ceiling spotlight, in the painting. By using these means, the picture got the effect of a stage space and the viewer was integrated into the action.

In 1992, in connection with the Olympic Games in Barcelona, a replica of the Spanish Pavilion was created in Avenida del Cardenal Vidal i Barraquer. Also Guernica was placed at the same place as to the exhibition as a copy.

Image content

Figures from Picasso's own iconography

The horse

As already mentioned, the horse is a symbol often encountered in Picasso for absolute suffering. It appears again and again in his depictions of the bullfight (Corrida) as well as in the Minotauromachy . What is unusual is that, compared to the more common fight in the arena, the opponents are horse and bull and not man and bull. The horse is always the victim, the bull grazes the mare with oral greed, an encrypted sexual act. In the Minotauromachy, a torera also appears in the action. With Guernica, however, it is questionable whether a sexual component is hidden, because compared to the usual corrida depictions, the bull and mare do not interact with each other. They could have their own spectrum of meanings. In many interpretations, the mare is seen as the symbol for the women of Guernica, who had to endure most of the suffering. On the other hand, Becht-Jördens and Wehmeier speak of a “symbiosis of suffering” of the mare and the bull, both of which are to be regarded as representative figures of the artist as well as of the powers with which he wrestles.

The mare is the dominant main motive. The central point in the picture that would have been given to Christ in the traditional triptych , its plastic, collage-like, faceted body that is detached from the surface, all these means ensure that the viewer is primarily interested in this figure.

The bull

The bull is far more difficult to interpret. Picasso had dealt with Freudian psychoanalysis years earlier . For him, the bull or the Minotaur embodies a lot: the force that breaks the boundaries of the irrational, rebelliousness, revolution, instinctuality or brutality. In contrast to the mare, he cannot be clearly assessed as a positive or negative figure. Picasso also adored him for his human nature, vitality and masculinity. Picasso himself gave almost no interpretation. When asked about the interpretation, he is said to have only explained that the bull means brutality, the horse the people.

In some interpretations, the bull is seen as a symbol for Franco or fascism, as it stands rigid and unharmed apart from everything. Others, on the other hand, see the bull as the embodiment of the life forces of Spain , as in Franco's dream and lie etching cycle . Evil is no longer personalized in Guernica. Still others come to the conclusion, based on the preliminary drawings - there the bull had a human head with Picasso's facial features - that the bull with the burning tail stands for the angry and excited Picasso.

The light bearer

In the opinion of the organizers of the Berlin Guernica documentation from 1975, the light bearer is an allegorical figure steeped in tradition , who stands for enlightenment , but also for political liberation - a comparable motif is shown in the New York Statue of Liberty . Critics of this theory criticize the fact that this interpretation is not applicable in Picasso's previous work. In the etching Minotauromachie from 1935, the light bearer is an innocent, virginal being who illuminates the brutal scene of mental and physical destruction. She bears the facial features of Marie-Thérèse Walter , Picasso's young lover at the time. So one could also assume that the figure does not come from images of a general cultural memory, but rather is composed of the artist's very personal contexts of meaning. On the other hand, a very similar light bearer appears - as well as other important motivic elements - in Hans Baldung Grien's woodcut The Bewitched Stallhand . There, too, a female figure with a torch in her hand leans through a window into the room, so that one could assume that Picasso was inspired by the woodcut. Another theory says that the light bearer symbolizes the world public, which looked stunned at the events in Spain. The connection with the world exhibition in which the picture stands speaks for this interpretation. In contrast to many of the other motifs, this figure was laid out in the pictorial concept from the start. The teardrop-shaped head belonging to the outstretched hand shows a plaintive expression and can be seen as a quote from the surrealistic painting Le Sommeil (Sleep) by Salvador Dalí from the same year.

The warrior

The warrior holds the broken sword in his right hand, while in his open left the drawing of the lines of fate stands out strongly. Originally, the fallen warrior with a raised fist with ears of wheat should be the central figure of the picture. His attitude should stand for the unbroken resistance of free Spain and proclaim hope. In the course of the work on the canvas, the figure disintegrates into body fragments and loses its originally intended role. The reason for this could be the May events in Barcelona in May 1937, when Stalinists took up arms against the liberal left, and a civil war within a civil war took place. But it could also have been the World's Fair's imperative to refrain from making political statements that forced Picasso to change his concept. But perhaps he had also come to the conclusion that the expressiveness of pain and agony could affect the viewer emotionally more than that of protest.

"Real" figures

The group of motifs, which symbolizes the real events, is added late in the picture. The incorrectly anatomically correct representation serves to over-accentuate important body parts. In addition, the faces serve as carriers of expression. Models for the representatives of suffering could have been pictures that Picasso saw as a three-year-old during the earthquake in Málaga in 1884. It was then that he suffered a lifelong severe trauma that came out with every sudden bang.

Mother with dead child (pietà)

This figure is reminiscent of the Christian representation of the mourning Mary , the mother of Jesus . It stands for the loss of close relatives that the whole population of Guernica suffered on the night of the bombing, when the lives of most of their families were wiped out.

Fleeing woman

On the right side of the picture a conflagration is raging, symbolized by seven flames. The fleeing woman emerges from the burning houses and into the cone of light generated by the light bearer. In keeping with the figure, Picasso puts emphasis on her musculoskeletal system. The disproportionately enlarged right leg seems like a weight to prevent her from escaping death. This figure could represent fear of death.

Burning woman

The woman burning in the houses behaves in the opposite way. Your head appears greatly enlarged, the rest of the body is optically downgraded. As with the fleeing woman, physiognomy is the central expression of the burning woman. This figure represents the victims and their deaths caused by the attack.

Ceiling lamp

The ceiling lamp is at the position in the picture where originally a sun motif with a halo encircled the fist of the warrior's outstretched arm. With the change in the role of the warrior, the sun motif became an interior prop, like the table on the left of the picture. This gave the picture a stronger stage setting. The ceiling lamp is the only object of our time (electric light). It replaces the light of the altarpieces with its salvation aspect with a "real" light (instead of the spirit eye as the great eye of God). In some interpretations it is therefore seen as the representation of a desolate world without Christian salvation. It points to the bombs dropped by airplanes, which is also indicated by the Spanish word play "la bombilla / la bomba" (bombilla = light bulb). Analogous to the curtain in Renaissance painting , the lamp can also be understood as a symbol for the enlightenment power of the arts.

Olive branch

The olive branch grows out of the warrior's fist. It is the only remaining symbol of hope that the war will soon end.

spear

The spear enters the horse from the top right of the wound. It could therefore stand for the bombs that brought death “from above”.

bird

The bird is a figure from general cultural memory. It could stand for the ancient Greek legend of the phoenix or for the dove of peace that comes from the biblical tradition. In the form of the dying dove, it could not stand for peace, but for annihilation, death, the breach of peace.

New perspective on the role of art in the face of war and violence

With the French Revolution and its social changes, the field of vision of art also changed. Until then, artists were employed by the nobility or the clergy, but now many of them had to eke out their lives in sometimes poor conditions. This also led to a change in the theme of war representations. While traditional painting often staged the war as a giant game with fair losers, the focus now was on the victims. In the spirit of Goya's Desastres de la Guerra , Picasso also took this new path: In Guernica there is no hero, no victory for good, no perpetrators, but the Apocalypse with all its atrocities.

The picture takes sides, but does not serve any political, religious or military interests. It sues against war and destruction. What is special about it is that Picasso does not document the events, but generalizes them and makes them accessible to emotional processing through their "expressive figures" (Imdahl). In this way, art makes it possible to overcome speechless impotence in the face of horror. This is their function of redemption, to which Christian iconography indicates. Guernica is therefore much more than an anti-war image, and certainly more than political propaganda art , it is - "in the guise of a history painting " - an "art-theoretical studio portrait " and as such nothing less than an " Ars Poetica of the visual arts" (Becht-Jördens, Wehmeier).

Picasso achieved a high level of comprehensibility through the use of universal, pictorial elementary forms similar to pictograms . This even goes beyond one's own culture - otherwise it could not be explained that Guernica is one of the most cited images in the world, whether as graffiti , poster , leaf painting or sculpture .

In 1944, a dialogue between the artist and a German soldier took place in Picasso's Paris studio in the Rue des Grands Augustins. The soldier saw a scaled down reproduction of the Guernica and asked: "Did you do that?" Picasso replied: "No, you!"

Simon Schama , a professor of art history, picked up the scene in the studio in his TV documentary Power of Art - Part 3 from 2007 and describes in a haunting way how the dialogue and the creation of the painting as well as the effect of the image created an icon .

reception

The contemporary press largely rejected Guernica. The respected art magazine Cahiers d'Art , which dedicated a double issue to Picasso, made a significant exception .

Paul Éluard, with whom Picasso was a close friend, wrote the poem The Victory of Guernica in 1938 , in which he took up motifs from the picture. Éluard also worked with Alain Resnais to produce his thirteen-minute short film documentary Guernica in 1950 .

A revue Lyrique - Guernica 1937 by the French director and poet Jean Mailland and Anna Prucnal , based on Picasso, tries to keep the memory of the massacre alive. Guernica had a significant influence on abstract expressionism among artists such as Pollock and Motherwell .

Michel Leiris formulates a poetic image of the painting:

" Guernica is the world turned into a furnished room ... and the black and white smells of this dying world ... threaten to represent our lives."

The Spanish painter Antonio Saura published a pamphlet Against the Guernica to transport the painting from New York to Madrid. Each paragraph begins with “I hate the Guernica”, “I hate the Guernica”, “I despise the Guernica”. A distorting mirror that throws light on the cultic veneration of the image. "I hate the Guernica because it is the relic of a betrayed world." - "I despise the Guernica because it demonstrates that some painters think when it is well known that painters should not think but paint."

In his Aesthetics of Resistance, Peter Weiss describes the apocalypse of Saint-Sever as one of the roots in Picasso's Guernica: The miniature of Beatus, from the eleventh century, showed the components of the composition used by Picasso in an as yet undisguised landscape.

The Protestant theologian and philosopher Paul Tillich gave an eulogy for Guernica. He called it a great Protestant work of art : it emphasizes that man is finite, subject to death; Above all, however, that he is alienated from his true being and dominated by demonic forces, forces of self-destruction.

José Luis Alcaine creates a connection between Guernica and the Hollywood film A Farewell to Arms (German: In Another Land ) by Frank Borzage . His profound knowledge of film history enabled him to demonstrate a series of similarities between Picasso's work of art and numerous shots that can be seen in a sequence. The screenplay for In Another Land was based on the novel of the same name by Ernest Hemingway , with whom Picasso was friends. Alcaine is certain that Picasso saw the film back then. The anti-war film opened in Paris in 1933 and was still shown in cinemas there in 1937 when it was painting Guernica. Gernika was destroyed by day. In contrast, the painting shows a nocturnal scene, as does the sequence in the Borzage film. Guernica reads from right to left, just like the movements in the film.

Reception in music

In 1937 the composer Paul Dessau composed a nearly 6-minute piece for piano solo with the title Guernica (after Picasso), which the picture served as a model. The work is based on a twelve-tone series and is dedicated to René Leibowitz .

Topicality

A tapestry-shaped copy of the painting, donated by Nelson Rockefeller in 1985 , hangs in the vestibule of the UN Security Council meeting room in the main UN building in New York City . It was imposed with the blue flag of the Security Council on February 4, 2003 at the request of the US government. The reason for this was a presentation scheduled for the following day by Colin Powell , then Secretary of State of the United States , which was supposed to prove the efforts of Iraq under Saddam Hussein for weapons of mass destruction . This was intended to achieve the approval of the Security Council and the world public for the Iraq war . In response to inquiries from the US media, diplomats said that the image was imposed with consideration for the public broadcast of the Security Council meeting.

The Berliner Zeitung commented on this process as follows:

“What does this little scene from the great reality testify to? Does it bear witness to the well-known - the weakness of art, its foolish and luxury existence? Politics, capital, public morality, they adorn themselves with it and ennoble their spaces and intentions - but only as long and as they please. Or does it not, on the contrary, show the power that images can emanate and of which one is obviously afraid?

Art can very well change the reality in the mind, and to change the thinking in the minds of the opponents of war, Colin Powell had come. On Wednesday in New York there was picture against picture: The CIA's slide show in the Security Council, photographed from the bird's-eye view from which the bombs will soon fall - and below in the foyer the frog's-eye view of the victims, a reminder of the shocking first bomb attack on a European city. The fact that Picasso's picture had to be covered only proves that the power of the espionage recordings was seen as jeopardized. Obviously you don't really trust your own pictures. The mural and the satellite photo are in direct competition. You can still remember the recordings marked 'Censored by US censors' from the first Gulf War. Now, with the blue cloth over 'Guernica', the next Gulf War, but the next censorship, has already begun.

The Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung ruled:

"In the pre-war media, politicians still fear the power of images beyond their control ... It was, according to a diplomat, not an 'appropriate backdrop' for Powell or the United States Ambassador to the United Nations, John Negroponte talking about war while being surrounded by screaming women, children and animals showing the suffering caused by bombing.

The decision to cover up Picasso's pictorial outcry […] is a symbolic act. It not only damages the memory that Picasso's picture of the event evokes, it also damages the human gift, in the clear awareness of suffering and in the face of the victims - be they too just painted - to argue about war or peace. "

The great-granddaughter of Henri Matisse , Sophie Matisse , completed Final Guernica in 2003 , a duplicate in almost identical canvas size of the monumental painting, which is not in gray-blue-black like the original in Madrid, but in bright colors.

In 1990 a Bundeswehr advertisement appeared in which Picasso's anti-war image was shown. Underneath it read "Enemy images are the fathers of war." This created a connection between the Picasso image and enemy images. The role of Germany was not discussed in the ad. The Lord Mayor of Pforzheim , a twin town of Gernika, Joachim Becker , complained to Defense Minister Gerhard Stoltenberg about the “completely falsifying way” in which the image was misused and expressed in writing his “deeply felt indignation”. Günter Grass published an appeal to Richard von Weizsäcker under the title “Das Geschändete Bild” in ZEIT with the request to ask the Federal Minister of Defense to apologize to the citizens of Guernica. Both initiatives had no consequences.

Status

The condition of the picture is extremely worrying. The structure of the picture has suffered so much through frequent rolling up, transporting and stretching that it is nowadays neglected to hang it around in a museum, let alone lend it out. In 1974 an unknown perpetrator sprayed paint on the picture. In the 1980s, attempts were made to strengthen the structure with a waxy layer on the back, but the added weight did the opposite. On the 75th anniversary of its completion in 2012, a robot checked the condition of the painting.

literature

- Gijs van Hensbergen: Guernica. Biography of an image , Siedler, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-88680-866-3 .

- Gereon Becht-Jördens: Picasso's Guernica as an art-theoretical program . In: Gereon Becht-Jördens, Peter M. Wehmeier: Picasso and Christian Iconography , Berlin 2003, pp. 209–237.

- Max Imdahl : On Picasso's picture “Guernica” . Incoherence and coherence as aspects of modern imagery. In: Imdahl: Gesammelte Schriften , Volume 1, Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1996. pp. 398–459, ISBN 3-518-58213-5 .

- Max Imdahl : Picasso's Guernica. An art monograph . Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-458-32506-9 .

- Annemarie Zeiller: Guernica and the audience . Reimer, Berlin 1996, ISBN 3-496-01155-6 .

- Ludwig Ullmann: Picasso and the war . Kerber, Bielefeld 1993, ISBN 3-924639-24-8 .

- Carlo Ginzburg : The sword and the lightbulb - Picasso's Guernica . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1999, ISBN 3-518-12103-0 .

- Juan Marin: Guernica ou le rapt des Ménines , Paris 1994.

- Siegfried P. Neumann: Pablo Picasso, Guernica and Art - The Image of the End of Barbarism . Lang, Frankfurt am Main 1992, ISBN 3-631-44325-0 .

- Ellen Oppler (Ed.): Picasso's Guernica , New York 1988.

- Werner Spies : Guernica and the 1937 World's Fair . In: Werner Spies: Kontinent Picasso , Prestel, Munich 1988, pp. 63–99, ISBN 978-3-7913-2952-9 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Paul Assall: 07/12/1937: Pablo Picasso presents his painting "Guernica". SWR2, July 12, 2017, accessed July 12, 2017 .

- ↑ Ulrich Baron: The story of Picasso's "Guernica". In: The world . April 22, 2007, accessed June 14, 2015 .

- ^ Gijs van Hensbergen: Guernica . Munich, 2007

- ↑ Michael Cario Klepsch: Picasso and National Socialism. Patmos, Düsseldorf 2007, p. 109.

- ↑ Michael Cario Klepsch: Picasso and National Socialism. Patmos, Düsseldorf 2007, p. 110.

- ↑ Max Beckmann returns. Sacha Verna on Deutschlandradio October 23, 2016

- ↑ When "Guernica" returned: Picasso's furious accusation against the war , Salzburger Nachrichten , September 7, 2016, accessed on September 7, 2016.

- ↑ See Herschel Chipp, Alan Wofsy (Ed.): Picasso's Watercolors, Drawings and Sculpture. A Comprehensive Illustrated Catalog 1885-1973. Spanish Civil War 1937-1939. The Picasso Project. Alan Wofsy, San Francisco 1997, nos. 37-102 to 37-147 (studies); 37-148 to 37-155 (states)

- ↑ See Picasso Project 37-074 to 37-087

- ↑ [1] 500 years of the Isenheim Altarpiece. badish newspaper

- ^ Exhibition in Berlin: "Picasso - the time after Guernica (1937-1973)": The most unsystematic person in the world. By Petra Kipphoff in ZEIT on December 18, 1992

- ↑ Cf. Becht-Jördens, Wehmeier, see below Literature, pp. 159–180, esp. 168f .; Pp. 209-237, esp. Pp. 228-235. For this interpretation see below in the chapter New View on the Role of Art in the Face of War and Violence.

- ↑ Monika Czernin , Melissa Müller : Picassos Friseur, Fischer, 2002, page 42. The thought is preceded by the comment in the book: “The result initially shocked some, the others - including his clients - missed the powerful statement. Picasso mastered it all his life to get rid of annoying questions with simplistic explanations. ”In the book it goes on:“ Even if the picture does not follow a simple symbolic interpretation, everyone soon understood that Picasso had created a prophecy of the coming catastrophes - fundamentally, powerful, timeless. "

- ↑ Yvonne Strüwing, 2002, Picasso - Dream and Lie Franco, Munich, GRIN Verlag. 2.4 "Guernica" and "Franco's dream and lie"

- ↑ 70 years of the social revolution in Spain: Graswurzel 2006

- ^ Wilhelm Fabry Museum Hilden

- ↑ Holger Liebs: Picasso's “Guernica” turns 70 - the invisible enemy. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung . May 19, 2010, accessed June 14, 2015 .

- ↑ Barry Stoner: ... the Spanish Pavilion. Guernica: Testimony of War. PBS.org, accessed February 20, 2019 .

- ↑ Monika Borgmann: Love to the last, before you go under. DIE ZEIT, May 2, 1997, accessed on March 31, 2017 .

- ↑ PAUL INGENDAAY: Look at this painting of horror between art and propaganda! Discussion on Gijs van Hensbergen: "Guernica". Biography of a picture . Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, June 4, 2007, accessed on March 31, 2017 .

- ↑ Philipp Greifenstein: About Picasso's “Guernica” - Paul Tillich. Video with interview. theologiestudierende.de, September 2, 2014, accessed on February 21, 2019 .

- ↑ RTVE.es: Días de cine: José Luis Alcaine cree que Picasso se inspiró en 'Adiós a las armas' para el Guernica (Spanish TV with sequences). dias-de-cine, December 9, 2011, accessed February 26, 2019 .

- ↑ Twelve-tone series on Guernica after Picasso by Paul Dessau

- ↑ Andreas Mertin: Truth and Lies. An image and its power. Magazine for Theology and Aesthetics, 2003, accessed February 21, 2019 .

- ↑ Andreas Schäfer: Picture against picture. In: Berliner Zeitung . March 7, 2003, accessed June 14, 2015 .

- ↑ Thomas Wagner: Victims undesirable. In: FAZ. February 10, 2003, accessed June 14, 2015 .

- ↑ Hella Boschmann: “Guernica” in strong colors. In: The world . February 15, 2003, accessed June 14, 2015 .

- ^ Sophie Matisse: Final Guernica (2003) , francisnaumann.com, accessed December 27, 2010.

- ^ Spiegel: Joachim Becker. Der Spiegel, October 1, 1990, accessed on March 27, 2017 .

- ↑ Koldehoff, Stefan, Koldehoff, Nora: To whom did van Gogh give his ear? Eichborn Verlag, Berlin, 2007, p. 333.

- ↑ Robot checks the condition of Picasso's “Guernica” , nachrichten.t-online.de, February 24, 2012, accessed on July 12, 2012.

Web links

- Repensando Guernica (an online offer from the Museo Reina Sofía , including a gigapixel photo of the painting)

- Guernica www.artchive.com

- Wiltrud Wößner: Interpretation with photographs (presented on June 15/16, 1994)

- Kai Artinger: Review by Gijs van Hensbergen: Guernica. The Biography of a Twentieth-Century Icon. Bloomsbury Publishing, London 2004, ISBN 1-58234-124-9 .

- Idsteiner Wednesday Society Compilation from: Max Imdahl (1925–1988): Picassos Guernica. Art monograph, Insel Taschenbuch , Gijs van Hensbergen: Guernica - Biography of a picture and Wiltrud Wössner, art historian: Interpretation of the picture Guernica

- Full text of Peter Weiss: The Aesthetics of Resistance Thorough analysis of the picture from p. 386 by Peter Weiss