Les Demoiselles d'Avignon

| Les Demoiselles d'Avignon |

|---|

| Pablo Picasso , 1907 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 243.9 x 233.7 cm |

| Museum of Modern Art, New York City

Link to the picture |

Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (oil on canvas, 243.9 × 233.7 cm) is a painting completed by Pablo Picasso in 1907 . It is seen as a turning point in the history of Western painting and at the same time heralded the impending Cubism . The work is owned by the Museum of Modern Art in New York .

Naming

The picture title Les Demoiselles d'Avignon comes from the year 1916 by Picasso's friend, the writer and art critic André Salmon . The word Avignon in the title referred to the Carrer d'Avinyó in Barcelona , which was known for its brothels and which Picasso lived near when he was young. The falsifying title that has become naturalized today refers to jokes that were circulating in Picasso's circle of friends. Picasso was not positive about the title of the picture and later rejected it.

meaning

Starting from the roots, Picasso reconsidered European art tradition and created a new artistic language from its elements. Picasso's concern was not to break with tradition, but to destroy convention. With the Demoiselles he succeeded , like in no other work of European painting, a reflection on painting and the beauty of art. Picasso not only dealt with the works of Uccello , Piero della Francesca , El Greco , Poussins , Ingres and Cézanne , but also with archaic art.

The role of the painting as a key work in modern art history has long been recognized. But for decades this assessment was blatantly disproportionate to the information that was available about its creation. For example, the notion that Picasso, influenced by African art, found a language of deformation here is widespread. The perplexity of his contemporaries towards Picasso's work in this phase of his work is evident in the terms with which they were associated. The Demoiselles Wilhelm Uhde appeared “Assyrian”, while Henri Rousseau called them “Egyptian” . Picasso's creative phase from the summer of 1907 to 1908 was known as the période nègre ( Negro period ) or Iberian period .

| Le bonheur de vivre |

|---|

| Henri Matisse , 1905/06 |

| Oil on canvas |

| 174 × 238 cm |

|

Barnes Foundation , Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Link to the picture |

From the art-historical point of view, the question has been discussed why the demoiselles should be seen as a pioneering image of Cubism and why the work did not lead to neofauvism or superfauvism, not to futurism , to expressionism , to a wild or tame primitivism or to abstraction. The only other possible continuation was Fauvism , but Picasso had already replaced this possible Fauvism with the Demoiselles , overcome it or declared it null and void. He gives the Fauves to understand that they are still too few "savages". He does not deny the pleasant rhythms in Matisse's Le bonheur de vivre , but he says that its picture is still too little rhythmic, that there is a deeper rhythm than this.

description

The painting Les Demoiselles d'Avignon shows five partly scantily clad, partly naked female figures from different angles in front of a background of various bluish tones. The viewer sees them from the front, from the side, crouching and diagonally from the front. A curtain is indicated on both sides, the left one is held by one hand; it has red-brown colors, the right curtain blue-ocher-colored. The foreground shows a still life with fruits on a table in the middle .

The bodies of the figures are shown abstracted in slightly angular shapes. White and bluish pieces of color next to and on the bodies create tension. There is a break between the three female figures on the left side of the picture and the two figures on the right side, who are characterized by mask-like distorted facial features, for which African masks could have served as models. The faces of the outer women are rather dark and shaded with hatching. One of the two women with a mask-like face sits with her back to the viewer, her head twisted in an unnatural way towards the viewer. Picasso used a method of representation that he had already practiced drawing a year earlier in Gósol, and that is able to represent several aspects and views of a body at the same time. The figures on the left, which reveal the influence of Iberian forms, are painted clearer and softer. Two women have raised their arms over their heads and present themselves to the viewer.

Emergence

Picasso worked on Les Demoiselles d'Avignon over nine months, from autumn 1906 to summer 1907. His estate documents 809 preliminary studies. This includes both sketches and large study sheets and other paintings. There is no comparable case in art history in which a single work was prepared with such difficulty.

Picasso's approach can be seen through the chain of preliminary studies. It consisted of two development processes, one formal and one thematic. They ran mentally separated, because most of the sketches reveal either a creative-formal or a thematic focus.

| Study for Les Demoiselles d'Avignon |

|---|

| Pablo Picasso , March 1907 |

| Oil on canvas |

|

Kunstmuseum Basel , Basel

Link to the picture |

After his return from Spain in autumn 1906, Picasso began in Paris, in the Bateau-Lavoir , with concrete preparatory work for the Demoiselles d'Avignon , which he continued throughout the winter. The first overall design from March 1907, today in Basel, shows an interior with seven people: five naked women and two clothed men. According to Picasso, the already clear scene in the Basel design shows the interior of a brothel on Carrer d'Avinyó in Barcelona. In the months that followed, however, Picasso changed the scenery so thoroughly that everything that had to do with the interior of a brothel was dropped. In addition, Picasso had dealt with such a topic earlier with depictions of prostitutes - for example The Harem from the summer of 1906. This picture, albeit in a smaller format, also formulated the idea of five naked women. From the art-historical point of view, it was concluded that the prostitute topic was no longer relevant for Picasso. The figure of a sailor with a skull appearing in another draft also suggests that Picasso had a history painting with an apparently allegorical meaning in mind.

For the general theme "Women who pose for assessment of their physical advantages" there is a traditional pattern of depicting three naked women in front of seated and standing male people: the judgment of Paris . A direct model was a painting by Rubens , whose variant of the Paris judgment is kept in Madrid's Prado and Picasso was well known.

From the point of view of CP Warncke, in the final version, Picasso now alludes to an ancient anecdote by defining the theme to five naked women, which gives the work a thematic and creative-formal unity. The painter Zeuxis was given the task of painting Helena , according to legend, the most beautiful human female figure. Zeuxis took the five most beautiful virgins of the island of Kroton as models in order to create a perfect ideal figure that does not exist in nature by combining their most beautiful bodies. The still life in the work also speaks for this view. All viewers noticed the unmotivated position of the still life in the alleged brothel scene, as well as the stylistic difference between the illusory painted fruits compared to the figures. These represent a further reference to a Zeuxis anecdote, according to which the ancient painter reproduced grapes in one of his paintings so faithfully that the birds were fooled by them and flew to nibble on them. This anecdote is of great importance in the history of painting; Zeuxis is considered to be the founder of illusion painting . In his work, Picasso goes against their rules and their normative aesthetics in a programmatic way.

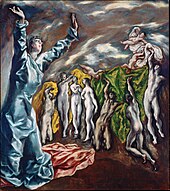

Even El Greco's painting The Fifth Seal of the Apocalypse , which was then the Spanish painter and friend of Picasso, Ignacio Zuloaga was one, has been considered by various art historians as a relevant influence. Picasso had seen the picture in Zuloaga's studio when he was working on the Demoiselles .

First reactions

Work on the painting was completed in July 1907. Picasso asked the German art dealer Wilhelm Uhde , who lives in Paris , to see it. Uhde, in turn, told Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler about his visit and the unusual picture.

The work has now been shown to a close circle of Picasso's friends. Guillaume Apollinaire , Félix Fénéon , André Derain , Georges Braque and Henri Matisse initially rejected the picture. They could neither interpret nor classify it.

First public exhibition in 1916 and current location

| Les Demoiselles d'Avignon by Jacques Doucet |

|---|

| Photograph by Pierre Legrain , 1929 |

|

Link to the picture |

The painting remained in Picasso's studio for a long time and was first presented to the public in July 1916 at the Art Moderne en France exhibition organized by Salmon at the Salon d'Antin in the Barbazanges gallery in Paris.

At the end of 1924, the fashion designer and art collector Jacques Doucet acquired the Demoiselles for his collection directly from Picasso's studio. Picasso had kept it there, facing the wall. The recommendation came from André Breton , who was employed part-time at Doucet as a librarian and artistic advisor and who had taken him to the studio. In April 1925 an illustration appeared in the magazine La Révolution surréaliste , for which Breton was one of the editors.

In 1939 the painting came into the possession of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which it was able to acquire with the help of the legacy of the patroness Lillie P. Bliss (1864–1931).

aftermath

The Spanish doctor and writer Jaime Salmon wrote a play in 2002 that has the same title as the picture. It is about the fictional prehistory and the fictional models of the picture in a brothel on Carrer d'Avinyó in Barcelona, to whose name the picture title refers.

literature

- Marie-Laure Bernadac, Paul de Bouchet: Picasso - Adventure History. Gallimard, Paris 1986.

- Pierre Daix , Joan Rosselet: Picasso - The Cubist Years 1907–1916. Thames and Hudson, London 1979, from the French Le Cubisme de Picasso, Catalog raisonné de l'œuvre translated by Dorothy S. Blair, ISBN 0-500-09134-X

- Siegfried Gohr : Pablo Picasso, life and work. "I don't search, I find" . DuMont, Cologne 2006, ISBN 978-3-8321-7743-0

- Klaus Herding : Pablo Picasso: Les Demoiselles d'Avignon. The challenge of the avant-garde. Frankfurt 1992 ISBN 3-596-10953-1

- Josep Palau i Fabre : Picasso - Cubism . (From the Catalan by Wolfgang J. Wegscheider), Könemann, Cologne 1998, ISBN 3-8290-1450-3

- Patricia Leighton: The White Peril and L'Art nègre; Picasso, Primitivism, and Anticolonialism. In: Kymberly N. Pinder, editor: Race-ing Art History . Routledge, New York 2002. ISBN 0-415-92760-9

- William Rubin : Picasso and Braque. The birth of cubism . (Original edition: Picasso and Braque, Pioneering Cubism , Museum of Modern Art, New York, September 24, 1989 to January 16, 1990, translated from English by Magda Moses and Bram Opstelten), Prestel, Munich 1990 ISBN 3-7913-1046 -1

- Carsten-Peter Warncke, Ingo F. Walther (Eds.): Pablo Picasso , Taschen, Cologne 2007, 2 volumes, ISBN 978-3-8228-3811-2

- Carsten-Peter Warncke: Picasso's “Les Demoiselles d´Avignon”. Construction of a legend. In: Karl Möseneder , Ed .: Dispute over pictures. From Byzantium to Duchamp . Reimer, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-496-01169-6 , pp. 201-220.

- different version: revolution and tradition. Picasso's “Les Demoiselles d´Avignon”, in: Ulrich Mölk (ed.), European turn of the century. Sciences, literature and art around 1900. Wallstein, Göttingen 1999, ISBN 3-89244-371-8 , pp. 92–112

Web links

- The painting on the website of the Museum of Modern Art

- Hanging in the Museum of Modern Art

- Christopher Green (PDF; 618 kB): Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (English)

- Karl-Konrad Seufert: Les Demoiselles D'Avignon by Pablo Picasso. Recent research on the artistic process. http://web.archive.org/web/20070611113422/http://web.uni-bamberg.de/~ba2kp3/text/demoiselles.htm

Individual evidence

- ↑ Learn to Paint: Cubism - History, Features, and Famous Artists. In: The information portal for all painting techniques. January 12, 2019, accessed on January 28, 2020 (German).

- ↑ a b c Jane Fluegel, William Rubin (ed.): Pablo Picasso - Retrospective in the Museum of Modern Art, New York , Prestel Verlag, Munich 1980, pp. 87-88.

- ↑ a b Carsten-Peter Warncke: Pablo Picasso , Volume 1, p. 160

- ↑ a b c d Carsten-Peter Warncke: Pablo Picasso , Volume 1, pp. 161–163

- ↑ Carsten-Peter Warncke: Pablo Picasso , 1991, vol. 1, pp. 143-145

- ↑ Patrick O'Brian: Pablo Picasso - A Biography . Ullstein, Frankfurt / M. - Berlin - Vienna 1982, pp. 216-217

- ^ A b c Carsten-Peter Warncke: Pablo Picasso , Volume 1, pp. 145–146

- ^ Carsten-Peter Warncke, Ingo F. Walther (Ed.): Pablo Picasso . Taschen Verlag, Cologne 2007, ISBN 978-3-8228-3811-2 , Volume 1, p. 176

- ↑ Josep Palau i Fabre : Picasso - Der Kubismus , 1998, p. 39

- ^ Josep Palau i Fabre : Picasso - Der Kubismus , 1998, p. 45

- ↑ Werner Spies , Die Weltgeschichte im Atelier , in: Werner Spies (Hrsg.): Picasso - To the hundredth birthday , Prestel, Munich, 3rd edition, 1981, ISBN 3-7913-0523-9 , p. 23 ff

- ^ Carsten-Peter Warncke: Pablo Picasso , Volume 1, p. 148

- ↑ Günter Metken , 3 de Mayo 1905 , in: Werner Spies (ed.): Picasso - For the hundredth birthday , Prestel, Munich, 3. Edition, 1981, ISBN 3-7913-0523-9 , p. 40

- ↑ With further references: John Golding: Visions of the Modern . University of California Press, Berkeley, 1994, pp. 105 f.

- ↑ Carter B. Horsley: The Shock of the Old . The City Review, 2003, accessed January 20, 2012

- ^ Judith Cousins, Comparative Biographical Chronology of Picasso and Braque in: William Rubin, Picasso and Braque , Prestel. Munich, 1990, ISBN 3-7913-1046-1 , p. 338

- ↑ Calvin Tomkins: Marcel Duchamp. A biography. Hanser, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-446-20110-6 , p. 296 f.

- ↑ Siegfried Gohr : I'm not looking, I find , p. 64 f

Illustrations

- ↑ Pablo Picasso: The Harem , summer 1906, oil on canvas, 163 × 120 cm, Cleveland Museum of Art