Lee Krasner

Leonore "Lee" Krasner , née Lena Krassner (born October 27, 1908 in Brooklyn , New York , † June 19, 1984 in New York ) was an American painter and collage artist. In the 1940s she belonged to the first generation of abstract expressionists in New York, later she married the action painting painter Jackson Pollock. During Pollock's lifetime and long after his death, Krasner's work stood in the shadow of his husband, whose sole heir and administrator of the estate she was. Only since the 1990s has her work been received as an independent one. She is now partially perceived as a "pioneer of abstract expressionism", her works are exhibited in the most important museums worldwide.

Live and act

childhood

Lee Krasner was the child of Russian-Jewish immigrants from Shpykiv (now Vinnytsia Oblast , Ukraine ). Her father Joseph Krassner fled to the USA in 1905 from the persecution of Jews there. In early 1908 he succeeded in bringing his wife Anna and her five children to New York. Nine months after the family reunited, Lena was born. The family was very religious and lived in modest circumstances in Brooklyn, where Krassner ran a fish stall in Blake Street Market. While Joseph spent a lot of time in the synagogue and was considered aloof and introverted, Anna took care of everyday life with the children. Home was Yiddish , Hebrew , Russian and English spoken.

Youth and education

According to Krasner, he wanted to become an artist at the age of thirteen. She began to copy pictures from fashion advertisements and did a lot of drawing. During this time she began to rebel against the Jewish religion at home and the Christian religion in school. Inspired by the feminist movements of the early 20th century, she dealt with the role of women in society. At about the age of fourteen she turned away from the Jewish religion for good and decided to attend Washington Irving High School , then New York's only school with an art class for girls. From 1922 she called herself instead of Lena Lenore. She later deleted an “s” from her last name Krassner and shortened the first name to Lee .

After graduating from Washington Irving High , she studied from 1926 to 1929 at the Woman's Art School of the Cooper Union . Here she was influenced by her teacher Victor Simon Pérard , who was less concerned with lifelike depiction than with perfect technique. Krasner copied her teacher's style so well that he hired her to draw illustrations for a textbook. The young artist set up her first studio with friends on the corner of 5th Avenue and 15th Street. The sculptor Moses Wainer Dykaar also worked in the same house and Krasner soon sat as a model for the painter. Dykaar suggested that she enroll in the Art Students League because the program there was better and less structured than at the Cooper Union. Krasner enrolled in George Bridgman's drawing class in 1928. Although the teacher and student had little to do with each other, it was here that they learned how to divide figures into geometric bodies, which meant a step towards abstraction. In 1929 she went to the renowned National Academy of Design , where she studied for the first time in a mixed-sex class. Here she enjoyed solid training in drawing, composition and technology. In the conservative environment of the school she stood out as a stubborn "troublemaker".

Self-portrait by Lee Krasner (1929) from the holdings of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Link to the picture

In 1929 Krasner met her fellow student Igor Pantuhoff, a Russian immigrant. Pantuhoff was a fan of modern painting and, together with Krasner, attended numerous related vernissages. Through him she got to know European artists like Arshile Gorky and Willem de Kooning. The pantuhoff, who flirted with his supposedly noble origins, took Krasner to parties and social occasions and was responsible for ensuring that she now dressed and made up more extravagantly. On the other hand, Pantuhoff was an alcoholic, cheated on and treated Krasner badly. She kept looking after him.

For Krasner, visits to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), which opened in 1929, had a lasting influence on her work . Here she saw pictures by Cézanne, Gauguin, Van Gogh, Seurat, Matisse and Picasso. Her works from the following period clearly show the influences of these artists. She herself described getting to know modern painting as “upheaval [...] similar to reading Schopenhauer or Nietzsche . A liberation, [...] a door was opened. "

In order to be admitted to a nude drawing course, Krasner worked on suitable presentation pieces in her parents' holiday home over the coming summer. In the end, she applied with a self-portrait that shows her, looking seriously and critically out of the picture, while painting in the garden. After looking at the oil painting, the chairman of the evaluation committee judged that Krasner had used a “dirty trick” and only pretended to have painted outside. The jurors didn't want to believe that a beginner could be that good. It was only with a lot of persuasion that the artist succeeded in winning participation in the course.

Numerous early works were lost in a fire that destroyed her parents' house in 1931. In 1932 Krasner left the National Academy of Design: Due to the miserable economic situation in the wake of the Great Depression , she was no longer able to pay the tuition fees. She then attended free courses at the City College of New York and began teacher training there. She also worked as a waiter in Greenwich Village , where she met other artists and writers such as B. met Harold Rosenberg . With Rosenberg, who later coined the term “action painting”, Krasner cultivated a lifelong friendship and intellectual exchange.

Participation in programs of the WPA

In 1935 she completed her training as a teacher, only to find that she definitely didn't want to teach, but rather to be an artist. From 1935 to 1943 she took part in the WPA Federal Art Project , which had been launched as a job creation program for artists as part of the New Deal . There she worked out murals that other artists had conceived. It wasn't until 1940 and 1941 that she got the chance to design her own abstract murals. The first project was finished before the design could be implemented. The second project had to leave Krasner before completion to help in the war economy. However, the sketches for both projects have been preserved. They show straight, biomorphic forms in primary colors with black, white and gray in the tradition of Mondrian , Miró and Picasso. Besides working on the murals, Krasner designed posters and decorated shop windows for the WPA.

Studied with Hans Hofmann

From 1937 to 1940 she studied as a scholarship holder at the private art school of the German-born painter Hans Hofmann . Through Hofmann's influence she turned more and more to cubist and free abstraction. Krasner liked Hofmann's analytical Cubism and the way he, who consciously accepted the canvas as two-dimensional space, arranged pictorial spaces. She learned from him how to use the "push & pull" technique to create spatiality from contrasting layers of color. During this time she dealt a lot with the approaches, colors and subjects of European modernism. Krasner, however, suffered from Hofmann's chauvinism. Once he commented on one of her works with the saying: “This is so good that you don't notice that it was painted by a woman.” During class, Hofmann sometimes tore up his students' drawings and pieced them together again to make things clear what should be improved. This may have inspired Krasner to later work on collages.

In the mid to late 1930s, Krasner was influenced by surrealists such as Giorgio de Chirico and the Italian Pittura Metafisica , of which u. a. the works Gansevoort I and II testify. She admired Edgar Allan Poe and Arthur Rimbaud . In 1939 she had a passage from Rimbaud's translation A Season in Hell written on an apartment wall: “To whom shall I hire myself out? What beast must one adore? What holy image attack? What hearts shall I break? What lie must I maintain? ”, The last sentence was highlighted in blue. Krasner's friends suspected that these lines also had something to do with the separation from Pantuhoff, who had moved to Florida without them.

First exhibitions and time with Jackson Pollock

Krasner is said to have met Jackson Pollock as early as 1936 at a loft party organized by the Artists Union . There he stepped on her feet while dancing, according to her own statement. Later she often told a different story about the first encounter: In November 1941, Krasner met the artist and curator John D. Graham and showed him her studio. Graham was so excited that he invited her to an exhibition where he contrasted French and American artists. As she read the list of participants, she came across the unfamiliar name Jackson Pollock . She decided to pay her colleague a visit to the studio. Krasner and Pollock met more often as a result and eventually became a couple. But this story, too, is based primarily on statements by Krasner.

Untitled charcoal drawing (1940) from the holdings of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

Link to the picture

In 1940 Krasner showed her work at the 4th Annual American Abstract Artists (AAA) exhibition in the American Fine Arts Galleries in New York. It was the first time her work had been discussed in the press - in this case by a New York Post critic who poked fun at abstract art.

In 1941 Krasner also took part in a collective exhibition of the AAA - together with Fernand Léger and Mondrian, who had become members of the group on an initiative by Krasner and other artists. Mondrian liked the strong inner rhythm of Krasner's work. He and Krasner had a love for boogie-woogie , the two of them went dancing together a few times. Mondrian later painted Broadway Boogie Woogie , inspired by the genre of music .

In the same year she met Pollock again in the context of the exhibition American and French Paintings at the McMillen Gallery, at which the two with u a. Willem de Kooning , Stuart Davis , Walt Kuhn , Picasso , Matisse , Braque , Bonnard and Modigliani took part. Impressed by Pollock's work, she introduced him to other painters, including de Kooning.

In 1942 she worked on a contract for the War Services Project , the final offshoot of the WPA: She oversaw the design of 19 window displays that were used to advertise civil defense courses at city colleges. Krasner made sure that Pollock was part of her team, which consisted of eight artists. After attending some of these civil defense courses - u. a. on the subject of explosives chemistry - Krasner decided to take photographs of the courses. The result was collages that combined photography , drawing and typography based on the model of the Russian constructivists . Only photographs of the collages have survived.

When Krasner and Pollock became a couple, their work became their top priority. From then on she did everything to support him, tried to control his alcohol consumption, became his secretary and manager. Triggered by Pollock's work, which had left Cubism behind, Krasner himself got into a three-year creative crisis from 1942 on. During this time she produced little more than the so-called “gray slabs”: canvases that were painted over many times, under whose thick, amorphous pigment layer “the picture [...] could not emerge”.

Little Images (1946-1950)

She was only able to free herself from this blockade in 1945: she and Pollock had married and, with the help of a loan from Peggy Guggenheim, bought a dilapidated house in Springs on Long Island . Krasner believed that country life would cure Pollock's depression and stop him drinking. At first he worked in the bedroom, but later used the house's barn as a studio, which also had space for larger works. Krasner now had the bedroom as a work space. From 1946 she began to paint the “Little Images” there: lively, shimmering abstractions, applied in several layers of oil paint, with repetitive pictorial elements that are reminiscent of Pollock's all-over technique . Initially, smaller formats with a diameter of 50 to 80 cm were created. A characteristic of these pictures is the controlled dripping technique used. Another is that they were not created on the easel, but worked horizontally. In contrast to Pollock, who was dealing with larger areas, Krasner did not work “standing in the picture”, but simply bent over it. Inspired by her husband, she proceeded more intuitively than before and tried to be one with nature instead of depicting it. Krasner, who was interested in characters and systems all her life , spoke of "her hieroglyphs" when referring to the "Little Images". Marcia Tucker later noticed that Krasner was working from right to left here, and related this to the Hebrew Krasner learned as a child.

In the winter of 1947, the cold forced Krasner to work on the first floor of the house near the stove. She created two mosaic tables from old wagon wheels. a. made of shells, pebbles, shards and costume jewelry. One of the tables was exhibited together with the "Little Images" in 1948 in the Bertha Schaefer Gallery in New York. Krasner received unreservedly positive reviews for this.

While Jackson Pollock's career was now meteoric and he was named the “greatest living American artist” in Life Magazine , Krasner remained as “Mrs. Pollock ”in the background. In the 1940s and 50s, she sometimes signed her works with “LK” or not at all in order to hide her identity as a woman.

First collage work (1950–1955)

Krasner had her first solo exhibition in 1951 at the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York. The 14 abstract paintings were largely received positively by the critics, but Krasner was not able to sell a single one. Plagued by self-doubt, she then turned to a series of black and white drawings, which she tore up again in a fit of disgust. When she reentered the studio - a converted smokehouse on the property in Springs - a few weeks later, she began gluing the torn pieces back together. In addition, she cut up old oil paintings and layered the whole thing together with other materials and parts of Pollock's discarded drawings on top of the unsold paintings from the Betty Parsons exhibition. In 1955 she exhibited these “collage paintings” at the New York Stable Gallery .

Prophecy (1956)

In the early 1950s, Pollock started drinking again after two years of abstinence. His condition rapidly deteriorated, which had a negative impact on the marriage and social life of the two artists. Krasner, who tried in vain to curb Pollock's alcohol consumption and at the same time promote his career, got health problems herself. In 1956 she painted a picture that differed from her previous work due to its intertwined, fleshy forms and colors, and which disturbed the artist herself. She named the picture Prophecy . Pollock assured her that it was "a good picture" and that she should "not think about it, just move on". Alfonso Ossorio , a friend and sponsor of the two, bought the picture immediately.

When Pollock finally started a relationship with the young Ruth Kligman, Krasner demanded a decision. She decided to go on a jointly planned trip to Europe on her own. On August 12, 1956, she learned that Pollock had had a fatal accident while intoxicated. His mistress was seriously injured in the car accident and her friend Edith Metzger was killed. Krasner returned to New York the following day.

Time after Pollock's death and other works and exhibitions

Earth Green Series (1956-1958)

Birth (1956) from the collection of the Reynolda House Museum of American Art

Link to the picture

Shortly after Pollock's death, three pictures were created that are seen in connection with Prophecy : Birth , Embrace and Three in Two . The works, which are inspired by Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon , show twitching, entwined, broken, strongly contoured forms in fleshy pink and disembodied eyes in portrait format. In their figuration, they opposed the predominant abstract aesthetic of the New York School . They seem to reflect Krasner's anger, guilt, pain and feelings of loss. When confronted with the question of how she could even paint during the period of mourning, Krasner replied at the time:

“Painting cannot be separated from life. It's one. It's like asking: Do I want to live? My answer is: yes - and I paint. "

These and 14 other pictures from the years 1956–57 form the Earth Green Series, they were honored in a 1958 solo exhibition at the Martha Jackson Gallery. Stuart Preston of the New York Times was impressed by Krasner's daring at the time. Art critic John Russell described the series' The Seasons as "one of the most remarkable pictures of its time".

Umber Series (1959-62)

After Pollock's death, Krasner had started to use his former studio, as it was the largest work space with the best lighting conditions. She was suffering from insomnia at the time. After her mother died in 1959, she suffered from depression. Now a series of large-format paintings was created, which are called “Night Journeys” or “Umber Series”: Since Krasner only wanted to work with colors in daylight, she limited herself to umber tones and white for these nighttime pictures. Thematically, she deals with birth , death and spirituality . In contrast to the subdued colors, the execution looks unusually raw and explosive. Krasner, who was only 1.60 meters tall, painted here with enormous physical effort and sometimes jumped up with the long-handled paintbrush to reach the furthest corners of the picture. She dragged and drew the brush across the canvas, using thick paint that dripped and splattered onto the surface. Although this dramatic work did not go down well with critics like Clement Greenberg, Krasner continued. The connection to Pollock is palpable in the images in the series, but Krasner tries to overcome his influence. The series includes 24 paintings.

Murals on Broadway

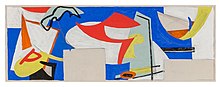

In 1958 Krasner was commissioned to design two murals for a corporate headquarters on Broadway . On this assignment, she worked with her nephew Ronald Stein. For the murals - the larger one is 26 m wide - irregularly broken Italian glass stones were used. You can see abstract, irregular, jagged shapes in rich red, black, blue and light green, which contrast with the rectangular, monotonous office buildings.

Primary Series (1960s)

At the beginning of the 1960s, Krasner broke his arm and began to paint with his left hand: She pressed the paint straight from the tube onto the picture and guided the movements of her left hand with the fingertips of her right. This more careful work, in which parts of the canvas remained white, is z. B. the pictures Through Blue and Icarus , which are counted in the Primary Series . Krasner now painted more with color again, with a relaxed, calligraphic gesture and bolder forms. The pictures appear flowery and exuberant. In 1965 a retrospective was dedicated to her at the Whitechapel Gallery in London: her first museum exhibition, which was shown in several British cities and in New York and met with a positive response.

At the same time, a number of abstract gouache drawings were made on handmade paper : Krasner experimented with just one or two unmixed colors and the structure of the paper - according to her own statement, because she enjoyed it and made it easy.

In 1968 Krasner exhibited at the Marlborough-Gerson Gallery: Lee Krasner: Recent Paintings was her first exhibition that was extensively discussed in the context of the feminist movement.

Further experimentation (1970s)

Krasner was reluctant to be associated with a recognizable style, she was constantly experimenting in the studio. At the beginning of the 1970s, the soft, corporeal structures in her paintings disappeared, making way for abstract shapes with hard edges in bright colors. The critic Robert Hughes described the pictures as "hot drums on the eyeball from 50 paces away [d]". They were, among other works, in 1973 in the Lee Krasner show. Large Paintings shown at the Whitney Museum of American Art . It was her most prominent retrospective to date, and it was enthusiastically received by critics.

The year before, Krasner had joined the group "Women in the Arts" and had demonstrated with around 300 other participants against the lack of attention given by women artists. Together with u. a. Louise Bourgeois and Chryssa , she campaigned for works by women to be shown in New York's major museums.

Eleven large-format collages by Krasner were shown in 1977 at the Pace Gallery in New York. The curator Bryan Robertson discovered old charcoal drawings from the 1930s in Krasner's studio. The artist cut up the drawings and processed the snippets in the new works.

In 1978, works by Krasner from the 1930s and 1940s were shown in the exhibition Abstract Expressionism: The Formative Years . Here she was honored for the first time as an abstract expressionist from the very beginning. The documentary Lee Krasner: The Long View by art historian Barbara Rose was shown at the Whitney Museum on the occasion of the exhibition .

Rose, a friend of Krasner's, curated the Krasner / Pollock exhibition three years later . A Working Relationship shown in East Hampton and New York. Krasner initially feared that the exhibition might turn out to be a “terrible stumbling block for [her] as an artist”. In fact, the New York Times spoke of a "symbiotic relationship" between the two artists on an equal footing. One reviewer was of the opinion that a “complete reassessment of the Krasner-Pollock connection” was necessary.

Lee Krasner died in New York Hospital in Manhattan in 1984 at the age of 75. She was buried next to her husband in the Springs cemetery. At a memorial service in her honor at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, u. a. Susan Sontag and Edward Albee . After her death, her property, the Pollock-Krasner House and Studio in Springs, East Hampton , was opened to the public. The Pollock-Krasner Foundation , established posthumously in 1985 at Krasner's will, supports artists and art institutions. 599 works are known of her.

Lee Krasner and Jackson Pollock

At the beginning of their relationship, Krasner brought Pollock, who was three years younger, into contact with European art and introduced him to other artists and people who were influential for him. She got him earning opportunities, organized his exhibitions and put her own ambitions aside. Krasner described Pollock as the artist who influenced her most besides Matisse and Picasso. Pollock encouraged Krasner when she had doubts about her work. In the last few years of his life, Pollock's growing alcohol problem marked their marriage. After his death, Krasner was Pollock's sole heir and became his estate administrator. Harold Rosenberg described her as a powerful artist widow who managed to drive up prices for contemporary American abstract art. According to BH Friedman, she was reluctant to sell Pollock's paintings out of business acumen but because she was very attached to them.

Believe

Krasner's parents were Jewish Orthodox , as a child Krasner was a believer and regularly attended church services. She admired her father's elaborately designed religious books and was fascinated by the Hebrew script. Little by little she lost her faith, which on the one hand had to do with reading Nietzsche and Schopenhauer . On the other hand, she didn't like the fact that in Orthodox Judaism women were considered inferior to men. According to her own admission, one day as a teenager, she announced to her parents that she had had enough of religion. Since then she has refused to practice it, but still saw herself as a Jewish woman.

Reception in film and literature

- In 1978 the 30-minute documentary Lee Krasner: The Long View by Barbara Rose was released

- In the biopic Pollock (2000) by and with Ed Harris , the artist was portrayed by Marcia Gay Harden . For her portrait of the “strong-willed, emancipated Lee Krasner” , Gay Harden received the award for Best Supporting Actress at the 2001 Academy Awards .

- The main character in John Updike's novel Seek My Face is u. a. Modeled after Lee Krasner.

Exhibitions (selection)

- 1951: first solo exhibition at the Betty Parsons Gallery in New York

- 1951: 9th Street Art Exhibition , New York

- 1955: Stable Gallery , New York

- 1958: Lee Krasner Recent Paintings , Martha Jackson Gallery , New York

- 1960: Recent Paintings by Lee Krasner at the Howard Wise Gallery , New York

- 1965: Lee Krasner. Paintings, Drawings and Collages at the Whitechapel Art Gallery , London

- 1973: Lee Krasner. Large Paintings in the Whitney Museum of Modern Art , New York

- 1977: Eleven Ways To Use the Words to See at Pace Gallery , New York

- 1978: Abstract Expressionism: The Formative Years at the Herbert F. Johnson Museum , the Seibu Museum, and the Whitney .

- 1979: Lee Krasner. Paintings 1959–1962 in the Pace Gallery , New York

- Since 1981 represented by the Robert Miller Gallery , New York

- 1981: Lee Krasner. Paintings 1956–1971 at the Janie C. Lee Gallery , Houston

- 1981: Krasner / Pollock. A Working Relationship at Guild Hall, Easthampton and the Gray Art Gallery and Study Center at New York University

- 1983: Lee Krasner. A retrospective at the Museum of Fine Arts , Houston

- 1984: Lee Krasner. A retrospective at the Museum Of Modern Art , New York

- 2019: Lee Krasner: Living Color at the Barbican Center, London

- 2019/2020: Lee Krasner. Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt , October 11, 2019 to January 12, 2020

- 2020: Lee Krasner. Living Color. Zentrum Paul Klee , Bern, February 7 to May 10, 2020 (extended to August 16, 2020)

Awards

- Outstanding Achievement in the Visual Arts , an award from the Women's Caucus for Art (1980)

- Distinguished Contributions to Higher Education , an award from the Stony Brook Foundation (1980)

- Chevalier de l'Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (1982)

- Honorary Doctorate in Fine Arts from the State University of New York, Stony Brook (1984)

List of the most important works

- 1929: Self Portrait, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- 1934: Gansevoort, Number 1, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- 1938: Still Life, Museum of Modern Art

- 1940: Seated Nude, Museum of Modern Art

- 1949: Composition , Philadelphia Museum of Art

- 1949: Untitled , Museum of Modern Art

- 1951: Number 3 (Untitled), Museum of Modern Art

- 1953: Untitled, National Gallery of Australia

- 1955: Milkweed , Albright-Knox Gallery

- 1961: Polar Stampede, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

- 1964: Untitled , Museum of Modern Art

- 1965: Night Creatures, Metropolitan Museum of Art

- 1966: Gaea , Metropolitan Museum of Art

- 1969: Gold Stone, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

- 1970: Comet , Robert Miller Gallery

- 1972: Rising Green , Metropolitan Museum of Art

- 1976: Imperative , National Gallery of Art

bibliography

Exhibition catalogs, monographs

- Marcia Tucker , Lee Krasner: Lee Krasner: Large Paintings . 1973.

- Barbara Rose , Lee Krasner: Lee Krasner: A Retrospective . Museum of Fine Arts, Houston / Museum of Modern Art New York 1983, ISBN 978-0-87070-415-4 .

- Bryan Robertson: Lee Krasner: Collages . Robert Miller Gallery, 1986, ISBN 0-944680-16-X .

- Sandor Kuthy, Ellen G. Landau: Lee Krasner - Jackson Pollock. Artist couples - artist friends / Dialogues d'artistes - résonances. Kunstmuseum Bern / Musée des Beaux-Arts de Berne 1989/1990.

- Richard Howard, John Cheim, Lee Krasner: Lee Krasner: Umber Paintings . Robert Miller Gallery, 1993, ISBN 0-944680-43-7 .

- Annette Reich, Svenja Kriebel: Abstract Expressionism in America. Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning , Hedda Sterne , Joan Mitchell , Helen Frankenthaler . Pfalzgalerie Kaiserslautern , 2001, ISBN 3-89422-114-3 .

- Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 .

- Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann (Eds.): Lee Krasner. With a joint foreword by the directors of the Barbican , the Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt , the Zentrum Paul Klee and the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao as well as texts by Eleanor Nairne, Katy Siegel, John Yau , Suzanne Hudson and an interview by Gail Levin with Lee Krasner . Hirmer Verlag , Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 .

literature

- Ralf Leisner: Lee Krasner - Jackson Pollock. A studio community 1942–1956 . scaneg Verlag, 1995, ISBN 3-89235-105-8 .

- Ines Janet Engelmann: Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner . Prestel, 2007, ISBN 978-3-7913-3881-1 .

Web links

- Lee Krasner's estate in the Archives of American Art

- Literature by and about Lee Krasner in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Lee Krasner in the German Digital Library

- The Pollock-Krasner Foundation (English)

- Pollock-Krasner House & Study Center (English)

- Lee Krasner. In: FemBio. Women's biography research (with references and citations).

Individual evidence

- ^ Doris Berger: Projected Art History. Myths and Images in the Biographies of Jackson Pollock and Jean-Michel Basquiat . transcript, Bielefeld 2009, ISBN 978-3-8376-1082-6 , p. 106 f., 119 .

- ↑ Lee Krasner. In: Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt. October 11, 2019, accessed May 28, 2020 .

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 4 .

- ↑ Steven Naifeh, Gregory White Smith: Jackson Pollock - An American Saga . Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1989, ISBN 0-517-56084-4 , pp. 367 .

- ↑ Bülent Gündüz: Jackson Pollock: The Biography . Parthas Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-86964-068-6 , p. 146

- ↑ Bülent Gündüz: Jackson Pollock - The Biography . Parthas Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-86964-068-6 , pp. 147 .

- ↑ Steven Naifeh, Gregory White Smith: Jackson Pollock - An American Saga . Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1989, ISBN 0-517-56084-4 , pp. 370-372 .

- ↑ Reframing Lee Krasner, the artist formerly known as Mrs Pollock , theguardian.com, May 12, 2019

- ↑ Bülent Gündüz: Jackson Pollock - The Biography . Parthas Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-86964-068-6 , pp. 148 .

- ↑ Barbara Rose: Lee Krasner: A Retrospective . Ed .: Houston Museum of Fine Arts, New York Museum of Modern Art. 1983, ISBN 0-87070-415-X , p. 18 .

- ↑ Barbara Rose: Lee Krasner: A Retrospective . Ed .: Houston Museum of Fine Arts, New York Museum of Modern Art. 1983, ISBN 0-87070-415-X , p. 15 .

- ↑ Bülent Gündüz: Jackson Pollock - The Biography . Parthas Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-86964-068-6 , pp. 148 f .

- ↑ Steven Naifeh, Gregory White Smith: Jackson Pollock - An American Saga . Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1989, ISBN 0-517-56084-4 , pp. 378-381 .

- ↑ Bülent Gündüz: Jackson Pollock - The Biography . Parthas Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-86964-068-6 , pp. 150 f .

- ↑ Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann (ed.): Lee Krasner . 1st edition. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 , pp. 190 .

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 66-68 .

- ↑ Bülent Gündüz: Jackson Pollock - The Biography . Parthas Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-86964-068-6 , pp. 149 f .

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 72-74 .

- ↑ Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann: Lee Krasner . 1st edition. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 , pp. 57, 190 .

- ↑ Rosenberg, Harold. In: Dictionary of Art Historians . February 21, 2018, accessed April 1, 2020 .

- ↑ a b Uta Grosenick, Ilka Becker (Ed.): Women Artists in the 20th and 21st Century . Taschen, 2001, ISBN 3-8228-5854-4 , pp. 276 .

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 75 .

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 133, 148 .

- ^ Frank N. Magill (Ed.): The 20th Century Go-N: Dictionary of World Biography . tape 8 . Routledge, London and New York 1999, ISBN 1-57958-047-5 , pp. 2023 .

- ↑ a b Lee Krasner - US Department of State. In: Art In Embassies. US Department of State, accessed February 13, 2020 (American English).

- ↑ Bülent Gündüz: Jackson Pollock - The Biography . Parthas Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-86964-068-6 , pp. 152 f .

- ↑ Cindy Nemser: Art Talk: Conversations with Twelve Women Artists . New York 1975, pp. 80-112.

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 122-128 .

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 139 .

- ^ Robert Hobbs: Lee Krasner's Skepticism and Her Emergent Postmodernism . In: Old City Publishing, Inc. (Ed.): Woman's Art Journal . tape 28 , 2007, pp. 3-10 , JSTOR : 2035812 .

- ↑ Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann (ed.): Lee Krasner . 1st edition. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 , pp. 195 .

- ↑ Bülent Gündüz: Jackson Pollock - The Biography . Parthas Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-86964-068-6 , pp. 155 .

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner. A biography . William Morrow / HarperCollins Publishers, New York 2011, ISBN 978-0-06-184525-3 , p. 102

- ↑ Bülent Gündüz: Jackson Pollock - The Biography . Parthas Verlag, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-86964-068-6 , pp. 157-160 .

- ↑ Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann (ed.): Lee Krasner . 1st edition. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 , pp. 196 .

- ↑ Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann (ed.): Lee Krasner . 1st edition. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 , pp. 197 .

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 190, 194 .

- ↑ Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann (ed.): Lee Krasner . 1st edition. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 , pp. 69 .

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 190 ff., 208, 225 .

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 219 f .

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 232 ff .

- ↑ Evelyn Toynton: Jackson Pollock . Yale University Press, New Haven & London 2012, ISBN 978-0-300-16325-4 , pp. 42 .

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 236 ff .

- ↑ Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann (ed.): Lee Krasner . 1st edition. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 , pp. 14-15, 198 .

- ^ Robert Hobbs: Lee Krasner: A Retrospective by Barbara Rose . In: Woman's Art Inc. (Ed.): Woman's Art Journal . tape 8 , no. 1 , 187, pp. 43-45 .

- ↑ Lee Krasner. In: House of Art. Retrieved April 11, 2020 .

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 241 ff .

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 245 .

- ↑ a b Gail Levin: Beyond The Pale . Ed .: Woman's Art Journal. tape 28 , no. 2 . Old City Publishing, Inc., 2007, p. 28-34 , JSTOR : 20358128 .

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 250, 254 f .

- ↑ Ben Cosgrove: Jackson Pollock: Rare Early Photos of the Action Painter at Work. In: Life Magazine. January 27, 2014, accessed April 11, 2020 (American English).

- ^ A b Susanne Kippenberger: The artist Lee Krasner: Die Unbeirrbare. Der Tagesspiegel, October 21, 2019, accessed on January 10, 2020 .

- ^ Anne Wagner: Lee Krasner as LK In: The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History. New York 1992

- ↑ Lilias Wigan: In Focus: The Bald Eagle, America's symbol, 'torn apart, deranged and fragmented' by Lee Krasner. In: Country Life. TI Media ltd., June 28, 2019, accessed on April 13, 2020 (English).

- ↑ Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann (ed.): Lee Krasner . 1st edition. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 , pp. 15, 44, 97, 205-206 .

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 266-308 .

- ↑ Kirk Varnedoe , Pepe Karmel: Jackson Pollock: Essays, Chronology, and Bibliography. Exhibition catalog. Museum of Modern Art , New York 1988, ISBN 0-87070-069-3 , p. 328: Chronology.

- ↑ a b Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann (ed.): Lee Krasner . 1st edition. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 , pp. 111 .

- ^ Jackie Wullschläger: Lee Krasner retrospective: the forgotten genius of Abstract Expressionism. In: Financial Times. May 30, 2019, accessed April 12, 2020 .

- ↑ Barbara Rose: Lee Krasner: A Retrospective . Ed .: Houston Museum of Fine Arts, New York Museum of Modern Art. 1983, ISBN 978-0-87070-415-4 , pp. 97 .

- ↑ Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann (ed.): Lee Krasner . 1st edition. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 , pp. 209 .

- ^ Property from an important private American Collection - Lee Krasner Sun Woman I. In: Sotheby's. Retrieved April 17, 2020 (English).

- ↑ Michael Lloyd and Michael Desmond,: Abstract Expressionism - Lee Krasner, Cool white. In: National Gallery Of Australia. Retrieved April 14, 2020 (English).

- ↑ Meredith Mendelsohn: The Emotionally Charged Paintings Lee Krasner Created after Pollock's Death. In: Artsy. November 13, 2017, accessed January 12, 2020 .

- ^ Lee Krasner The Umber Paintings, 1959-1962. In: Kasmin Gallery. Retrieved April 17, 2020 .

- ^ Caroline Hannah: Crafting Manhattan. In: American Craft Council. September 19, 2011, accessed April 14, 2020 .

- ↑ Lee Krasner in New York IV: Giant Mosaic on Broadway. In: Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt. December 19, 2019, accessed April 14, 2020 .

- ↑ Ornament and Obsolescence: Lee Krasner's Mosaics for Wall Street. In: The Courtauld Institute Of Art. Retrieved April 14, 2020 .

- ↑ Barbara Rose: Lee Krasner: A Retrospective . Ed .: Houston Museum of Fine Arts, New York Museum of Modern Art. 1983, ISBN 0-87070-415-X , p. 130 .

- ↑ Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann (ed.): Lee Krasner . 1st edition. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 , pp. 129 .

- ↑ Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann (ed.): Lee Krasner . 1st edition. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 , pp. 213 .

- ↑ Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann (ed.): Lee Krasner . 1st edition. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 , pp. 157 .

- ↑ Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann (ed.): Lee Krasner . 1st edition. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 , pp. 214 .

- ↑ Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann (ed.): Lee Krasner . 1st edition. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 , pp. 163 .

- ↑ Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann (ed.): Lee Krasner . 1st edition. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 , pp. 217 .

- ↑ Helen A. Harrison: Art; Krasner-Pollock Show Traces a Partnership. In: The New York Times. September 6, 1981, accessed February 4, 2020 .

- ↑ Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann (ed.): Lee Krasner . 1st edition. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 , pp. 218 .

- ↑ Eleanor Nairne, Ilka Voermann (ed.): Lee Krasner . 1st edition. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3296-0 , pp. 220 .

- ↑ History | Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center. In: Stony Brook University. Retrieved March 5, 2020 .

- ↑ About. In: The Pollock Krasner Foundation. Retrieved March 5, 2020 (American English).

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 173, 188, 190, 204, 208 .

- ^ Anne Middleton Wagner: Three Artists (three women) . University of California Press, Berkeley 1997, ISBN 0-520-20608-8 , pp. 142 .

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 209, 305 .

- ^ Gail Levin: Lee Krasner - A biography . Thames & Hudson, London 2019, ISBN 978-0-500-29528-1 , pp. 289 ff .

- ^ Anne Middleton Wagner: Three Artists (three women) . University of California Press, Berkeley 1997, ISBN 0-520-20608-8 , pp. 127 .

- ↑ Barbara Rose: Lee Krasner: the long view. American Federation of Arts, 1978, accessed February 4, 2020 .

- ^ Ulrich Kriest: Pollock. In: film service . 12/2002

- ^ The beauty of being oneself. In: The Guardian. April 19, 2003, accessed March 3, 2020 .

- ^ Exhibition Lee Krasner. In: schirn.de. Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt am Main GmbH, October 11, 2019, accessed on December 30, 2019 .

- ↑ Past Honorees | Women's Caucus for Art. Retrieved February 4, 2020 (American English).

- ↑ Self-Portrait approx. 1929. In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed March 8, 2020 (English).

- ↑ Gansevoort, Number 1 1934. In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed March 8, 2020 (English).

- ↑ Lee Krasner. Still life. 1938. In: The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved March 8, 2020 .

- ↑ Lee Krasner. Seated nude. 1940. In: The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved March 8, 2020 .

- ^ Collections Object: Composition. In: Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved March 8, 2020 .

- ↑ Lee Krasner. Untitled. 1949. In: The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved March 8, 2020 (English).

- ↑ Lee Krasner. Number 3 (Untitled). 1951. In: The Museum of Modern Art. Accessed March 8, 2020 .

- ↑ Abstract Expressionism - Learn More | Lee Krasner | Untitled. In: National Gallery Of Australia. Retrieved March 8, 2020 .

- ↑ Milkweed. In: Albright-Knox Art Gallery. Retrieved March 8, 2020 .

- ↑ Lee Krasner, Polar Stampede, 1960. In: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved March 8, 2020 (English).

- ↑ Lee Krasner. Untitled. 1964. In: The Museum of Modern Art. Accessed March 8, 2020 .

- ^ Night Creatures. In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed March 8, 2020 .

- ↑ Lee Krasner. Gaea. 1966. In: The Museum of Modern Art. Accessed March 8, 2020 .

- ^ Gold Stone, from the Primary Series - Lee Krasner. In: Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. September 20, 2017, accessed March 8, 2020 .

- ↑ Lee Krasner in 'Abstraction' at Robert Miller Gallery - new york art tours. In: newyorkarttours.com. Retrieved March 8, 2020 .

- ^ Rising Green 1972. In: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed March 8, 2020 (English).

- ↑ Artist Info. In: National Gallery of Art. Accessed March 8, 2020 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Krasner, Lee |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Krasner, Leonore; Krassner, Lena (maiden name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American painter and collage artist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 27, 1908 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Brooklyn , New York |

| DATE OF DEATH | June 19, 1984 |

| Place of death | new York |