Bachelor machine

Bachelor machine (French "Machine Célibataire", English "Bachelor Machine") is a term that Marcel Duchamp used from around 1913 in connection with parts of his work, which he put together from 1915 to 1923 for the large glass . 1954, in The Bachelor Machines (French: Les Machines Celibataires ), Michel Carrouges expanded the term: According to Carrouges, a “Bachelor machine ” is a fantastic image that converts love into a mechanism of death. It consists of two figurative areas, one sexual and one mechanical, both of which are again divided into a male and a female area.

Concept history

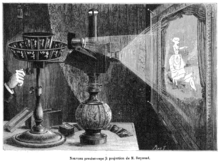

| External illustration |

Duchamp initially referred to the lower part of his work The newlyweds / bride undressed by her bachelors, even (French: La Mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même ), also known as the large glass , expressly as a "bachelor machine". In the lower part of the large glass, the bachelors are on the left, who, with their desire for the bride, start the chocolate grater on the right.

Later, in “Les Machines Celibataires” by Carrouges, the term bachelor machine became the leitmotif of an analysis of the mechanistic ideas about social, erotic-sexual and religious relationships that varied in art and literature between about 1850 and 1925 . The mechanistic worldview of this time had produced fantastic ideas about the mechanical functioning of history, about mechanics in the relationship of the sexes to one another and about the relationship of man to the mechanical dictation of a higher mental authority. Carrouges reveals the structure of a myth of the “bachelor machine” that connects Duchamp's work “Big Glass” and the machine in Franz Kafka's story In the Penal Colony . The myth and its structure also appear in the works of other artists and writers of the time, often as the imagination of erotically charged machines and devices that replace natural reproduction.

“We are with the myth in the time of Freud , the machines, the horror characters, the discovery of the fourth dimension , atheism , the militant bachelorhood of both sexes with the renunciation of procreation . A sexual and erotic connotation is read into inventions of the time , and the technical innovations are used as metaphors for a closed cycle: Alfred Jarry, for example, the bicycle and the electric chair in Surmâle , Duchamp the bicycle, the coffee grinder, the chocolate grater and the optical devices, Kafka the printing press, Villiers de l'Isle-Adam the androids , science fiction literature the computer and the rocket . "

In the climate of social strife in western Europe in the 1970s, ideas about bachelor machines were reinterpreted and expanded. In 1972 , Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, in “ Anti-Oedipus , Capitalism and Schizophrenia”, refer to ideas of a machine unconscious developed by Jacques Lacan , but also to Carrouges' theory and Duchamp's concept.

The major art exhibition “Junggesellenmaschinen / Les Machines Célibataires” curated by Harald Szeemann in 1975 attempts to visualize this myth. She traveled to 9 exhibition venues in Europe, including the Venice Biennale , the Museum of the 20th Century (now the Museum of Modern Art Ludwig Foundation ) in Vienna and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. The exhibition introduced the historical background of technical and social upheavals, which, among other things, continue to have an effect as digitization to this day (see “Cyberspace and Bachelor Machines” in Ars Electronica ARTificial Intelligence & ARTificial ART ). Due to the exhibitions and the reception of the catalog, the term became a well-known code in the cultural scene.

concept

A bachelor machine is a mental machine which, in a simple variant, consists of two levels that can be understood based on Sigmund Freud's subdivision into “ super-ego ” , “me” and “it” . In bachelor machines like the “Big Glass” by Duchamp and the machine in the penal colony of Kafka there is an upper zone with an inscription (a code), remotely comparable to the superego , “which, through a draftsman, transfers the message to a lower zone passes on: with Kafka it is the writing of the judgment in the back of the convicted person using the harrow. ”A third zone, comparable to the Es , a displacement camp , libido reservoir and the last bulwark of the will to live no longer exists in a bachelor machine or is extinguished in it. Only the upper zone has power, which enacts authoritarian regulations, fantasizes about social necessities, draws up inhuman schedules, controls their absolute compliance, and programs and seamlessly monitors the sequence of meaningless future events. "This reduction to two zones explains why the inscriptions or tortures always come from the upper zone and are always successful (...)."

Myth and environment

The myth of the bachelor machine is related to the typical interest in fictional machines at the beginning of science fiction literature among authors such as HG Wells , Jules Verne or George Henry Weiss (pseudonym Francis Flagg) with his story The Heads of Apex .

Like Jules Verne, Max Ernst and Francis Picabia, Marcel Duchamp read the richly illustrated magazine La Nature. Revue des sciences et de leurs applications aux arts et à l'industrie (Nature. Journal of the sciences and their applications in the arts and in industry), in which several writers and artists found their inspiration for “metaphorical machines”.

The current meaning is already recognizable in 1940 in the novel "Morel's Invention" by Adolfo Bioy Casares : Morel's invention is a machine that takes in living beings to record a sequence of their lives according to the logic of a bachelor machine as a dead three-dimensional recording, similar to an endlessly repeated film loop, to reproduce. In this picture , characteristics of the digital age functioning as self-archiving are already poetically anticipated.

The work The Myth of the Machine , published in 1967 by Lewis Mumford , does not explicitly refer to bachelor machines , but describes the emergence and development of civilization in a similarly critical sense: as the construction process of a hierarchically structured, technical-cultural mega-machine , which is guided by the power interests of the organizers and functionalized people as part of a militarily organized social machine. Mumford tries to describe interlocking social processes (state machine), together with technical achievements, as civilization in its actual historical development , as in a machine .

In contrast, the bachelor machines devised by artists and writers aim directly at the recipient's imagination . As inhuman as bachelor machines are for their imagined victims, as artistic inventions they are directed against mechanistic models of rule: “Bachelor machines are machines that negate each other. They do not affirm the rule of the technical and the mechanical, but sabotage them, and each of them testifies in its own way to the protest of the individual spirit against mechanical and mechanizing thinking. "

Michel Carrouges' analysis shows that bachelor machines are more than just fantastic images without reference to reality. Manfred Pabst: “When analyzing the psychological functions, Lacan starts from the machine model when he states that even if all people have disappeared from the earth, imaginary images still exist in mirrors.” Pabst quotes Lacan: “One materialistic definition of consciousness therefore provides a consciousness machine of the imaginary, which always comes into being when 'a surface is given in such a way that it can produce what is called an image' . "

In “Anti-Oedipus”, Deleuze and Guattari, in contrast to Lacan, condense the idea of a productively thought machine unconscious into the concept of the dream machine (French: machine désirante, literally translated: desire machine): “In the excessive machine vocabulary of the anti-Œdipe everything becomes a machine: desire, society, language, body, life, economy, literature, painting, imagination, schizophrenia, capitalism. "

Jean Baudrillard remarked in the 1980s: “Am I now a human being or am I a machine? Today there is no longer an answer to this question: real and subjectively, I am human, virtually and practically, I am a machine. ”The global mega-machine of civilization has embraced all people. At the digital interface, the simulated reality becomes virtual reality , and people “prefer to indulge in the acting of thinking than thinking itself”.

Bachelor machine collection

- The machines in the novels by Raymond Roussel , Locus Solus and Impressions from Africa (Impressions d'Afrique)

- The Pit and the Pendulum at Edgar Allan Poe

- The bicycle, the superman and the electric armchair in The Superman (Le Surmâle) by Alfred Jarry .

literature

- Michel Carrouges: Les Machines Célibataires. Arcanes, Paris 1954.

- Michel Carrouges, Marcel Duchamp: Les Machines Célibataires. Editions du Chêne, Paris 1976, ISBN 2-85108-074-1 , ISBN 978-2-85108-074-5 .

- Michel Carrouges: The Bachelor Machines . zero sharp, Berlin 2019, ISBN 978-3-945421-09-3 .

- Adolfo Bioy Casares: Morels Invention , Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-518-41426-7 , ISBN 978-3-518-41426-2 (1940 in the original: La invención de Morel ).

- Jean Clair, Harald Szeemann (eds.): Junggesellenmaschinen / Les machines Célibataires. Exhibition catalog. Alfieri, Venezia 1975.

- Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari: Anti-Oedipus. Capitalism and schizophrenia. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1974 (orig. 1972).

- Heiko Schmid: Metaphysical machines. Techno-imaginative developments and their history in art and culture. transcript Verlag, Bielefeld 2016, ISBN 978-3-8376-3622-2 .

- Marcel Duchamp: Notes and Projects for The Large Glass , A. Schwarz (Ed.). Thames & Hudson, London 1969.

- Alfred Jarry: The Superman 1969 (Original edition: Le Surmâle, Paris 1902).

- Franz Kafka: In the penal colony. Kurt Wolff, Leipzig 1919.

- Hans Ulrich Reck, Harald Szeemann (Ed.): Bachelor machines , extended new edition. Vienna, Springer Verlag, 1999

- Annette Runte (ed.): Literary 'bachelor machines' and the aesthetics of neutralization / Machine littéraire, machine célibataire et 'genre neutre'. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2011, ISBN 978-3-8260-4107-5 .

Individual evidence

- ^ Marcel Duchamp: Notes and Projects for The Large Glass . Ed .: A. Schwarz. Thames & Hudson, London 1969, pp. 209 (note 140).

- ↑ Michel Carrouges: Instructions for use: Bachelor machines / Les machines Célibataires . Ed .: Jean Clair, Harald Szeemann. Alfieri, Venezia 1975, p. 21.1 ff .

- ^ Harald Szeemann: Bachelor machines : Junggesellenmaschinen / Les machines Célibataires . Ed .: Jean Clair, Harald Szeemann. Alfieri, Venezia 1975, p. 5.1 .

- ^ Harald Szeemann: Bachelor machines : Junggesellenmaschinen / Les machines Célibataires . Ed .: Jean Clair, Harald Szeemann. Alfieri, Venezia 1975, p. 5.2 f .

- ^ Harald Szeemann: Bachelor machines : Junggesellenmaschinen / Les machines Célibataires . Ed .: Jean Clair, Harald Szeemann. Alfieri, Venezia 1975, p. 7.2 f .

- ↑ Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari: Anti-Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia I . Suhrkamp, Frankfurt aM 1974, p. 25.1 f . (First edition: 1972).

- ^ Harald Szeemann: Junggesellenmaschinen / Les machines Célibataires . Ed .: Jean Clair, Harald Szeemann. Alfieri, Venezia 1975, p. 4.3 .

- ↑ Florian Brody , Mario Veitl: ARTificial Intelligence & ARTificial ART in: Digitale Träume Virtuelle Welten, Volume 02. Ars Electronica Archive, accessed on March 16, 2009 .

- ↑ See Harald Szeemann: Junggesellenmaschinen: Junggesellenmaschinen / Les machines Célibataires . Ed .: Jean Clair, Harald Szeemann. Alfieri, Venezia 1975, p. 5.3-7.2 .

- ↑ See Harald Szeemann: Junggesellenmaschinen: Junggesellenmaschinen / Les machines Célibataires . Ed .: Jean Clair, Harald Szeemann. Alfieri, Venezia 1975, p. 7.1 .

- ^ Francis Flagg: The Heads of Apex. In: Project Gutenberg. October 1931, accessed March 19, 2010 .

- ↑ Manuel Chemineau: La Nature . A picture essay. In: Brigitte Felderer (Hrsg.): Catalog for the exhibition "Wunschmaschine Welterfindung" . Springer, Vienna 1996.

- ^ Jean Clair: The last machine: Bachelor machines / Les machines Célibataires . Ed .: Jean Clair, Harald Szeemann. Alfieri, Venezia 1975, p. 180 ff .

- ↑ compare Lewis Mumford: Myth of the Machine . Culture, technology and power. Europa Verlags-AG, Vienna 1974, ISBN 3-203-50491-X , p. 23.2–24.1 (English: The Myth of the Machine . Translated by Liesl Nürenberger, Arpad Hälbig, 855 pages).

- ^ Rita Bischof: Teleskopagen, optional . In: The West . tape 29 . Vittorio Klostermann, 2001, ISBN 978-3-465-03157-4 , p. 234.2 (442 pages).

- ↑ Manfred Pabst: Image, language, subject: dream texts and discourse effects in Freud, Lacan, Derrida, Beckett and Deleuze / Guattari . Königshausen & Neumann, 2004, ISBN 3-8260-2670-5 , p. 252.2 + 252.4 .

- ↑ Henning Schmidgen: The unconscious of the machines. Conceptions of the psychic in Guattari, Deleuze and Lacan. Fink, Munich 1997, p. 10 .

- ↑ Jean Baudrillard: Video world and fractal subject . In: Ars Electronica (Ed.): Art of the scene . Linz 1988 (French, 90.146.8.18 [accessed February 9, 2010]).