Saken

The Saks ( Shaka in India , Sakā in Persia ) were (perhaps mainly) Iranian- speaking nomad associations in Central Asia .

In a narrower sense, ancient historical research most likely describes Iranian tribal groups as "Saken" who lived in the 8th – 1st centuries. Century BC Lived in the steppes of eastern Central Asia . In ancient Iranian studies , some authors refer to the “sakā” in the broader sense as all Iranian steppe nomads from the 8th – 1st centuries. Century BC BC. Archeology sees these saks as Central Asian representatives of the Scythian culture .

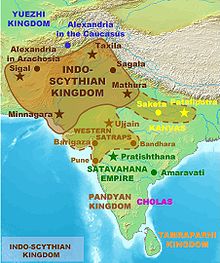

The originally nomadic Saks became partially settled in the western Tarim basin and in the region around the Syr Darja from the 7th / 6th century . With the expansion of the Yuezhi in the 2nd century BC Some Saks emigrated from Syr Darja to the region named after them Sistan and the north Indian region of Gandhara , from where they jointly founded the kingdom of the Indo-Scythians or Indo-Saks (approx. End of the 2nd century BC - Beginning of the 1st century AD), whose regional successor states in western India continued into the 4th century AD. In the Tarim Basin, Saki texts were written until the 10th century AD.

Use of the name "Saken"

After Herodotus, the Scythians were called Saken ( sakā ) by the Persians . As in ancient Europe the collective term "Skythe", in sources of the old Persian Achaemenid Empire the name sakā / "Sake" was often simply a general name for every steppe inhabitant, for example the ancient sub-region Sakasene in the kingdom of Albania in the Caucasus (today's Azerbaijan ) and also the The nearby city of Sheki takes its name from the ancient Persian sakā , although Scythian nomads immigrated to this region from the Black Sea region in ancient times . Following on from these two traditions, ancient historical literature sometimes mentions all the “Scythian” equestrian peoples who were culturally very close to one another around the 8th century BC. Chr. – 1. Century BC Chr./ 3rd century. Chr. Between the lower Danube , Altai , southern Siberia and Oxus ( Amu Darya ) in general terms "Scythians" called in Iranological against it as "Saken" or literature Saka .

In general, however, it is customary to distinguish between the clearly distinguishable groups of the Scythians in the narrower sense (southern Russian-Ukrainian steppes approx. 8th - 3rd century BC), Sarmatians (initially further east, 3rd century BC - 3rd century AD in the former Scythian area), massagers (6th – 3rd century BC around the Aral Sea ) and the Saken in the narrower sense in eastern Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan and in western Xinjiang . In addition, the carriers of the Iron Age Scythian archaeological cultures in southern Siberia and in the Altai ( Aldy-Bel culture , Tagar culture , Sagly-Baschi culture , Pasyryk stage , Tes stage ) are often distinguished from them (sometimes under the collective term " Altai-Scythians "summarized).

It has not yet been clarified which tribal associations and tribal confederations in the area of the Saks in the narrower sense existed (see also ethnogenesis ). Greek authors, especially Herodotus , reproduce myths about the tribes far to the east, including the Melanchlanes (= black coats ), the Hypoerboraeans (= living beyond the north), the Arimaspen (= one-eyed; Herodotus himself does not believe in their existence), the "Gold-guarding griffins" (after the archaeologically often verifiable mythical animal griffin ), the Argippaioi and the Issedonen . The Issedonen are sometimes hypothetically associated with the Wusun or with the Sakic group of Asii mentioned later . All in all, however, these distant narratives are unreliable and too legendary for reliable assignments and localizations. A few centuries later, Strabo mentions other tribal groups in the Sakian area: the Asii , Pasiani (Gasiani) , Tochari (in the 19th and early 20th centuries raised to give their names to the Tocharian languages , which was probably wrong, the established name of these languages is therefore misleading ) and the sacarauli . This information is also uncertain and difficult to localize from a great distance. In spite of numerous hypotheses being formed, it is therefore not possible to clarify the Saki tribal associations with certainty.

language

Most or all of the Saaks in the narrower sense who lived up to the 2nd century BC When nomads lived between Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and West China, they spoke the Sakian language , which is only well documented in two far eastern dialects in what is now West China, in the west of the Tarim Basin . The Saks had lived there since the 7th century BC. BC settled. The Saks, which have existed since the 2nd century BC When they immigrated to the area between Sistan and Northwest India, foreign languages were used as written language . Traditional idioms, personal names and foreign words reveal a language similar to that of the traditional Sakic language in western China. From the early nomadic period of the Saks, only one script found in the burial mound of Issyk (4th / 3rd century BC), which was not convincingly deciphered despite several attempts at deciphering, is known, the great similarity to later, likewise not deciphered inscriptions in the historical region Bactria has, also its designation as "Sakische script" is controversial, its language and reading is so far unknown (see article Issyk-Baktrien-Schrift ).

Sakic Buddhist and profane texts were found in the area of the ancient kingdom of Hotan in southwestern Tarim, more precisely in Hotan (Khotan) and the surrounding area, therefore the term Khotan-Saken is often used. Other texts come from Tumxuk and the surrounding area in north-western Tarim. In the area around Taxkorgan ( site of the Stone City ), already located southwest in the Pamir , Sakic was spoken in antiquity, where similar Iranian languages are spoken to this day. Whether Sakish was also spoken in the intermediate cities of Kashgar and Yarkant at that time is well conceivable, but cannot be clarified, because the Buddhist texts there were not written in native languages, but in Prakrit , a foreign language from Central India . The texts preserved in the dry desert climate of the Taklamakan date from a relatively late, early medieval period in the 7th – 10th centuries. Century. The use and transcript of Sakian ended because of the Tibetan government Turkic Uyghur settled in the Tarim Basin and regional empires founded, making the Uighur gradually as already established written language and respected language of the upper classes, the Sakan, as well as the regional senior Tocharian languages , repressed and so the Saks and Tochars assimilated into the Uighurs .

The Sakic language is assigned to the south- east Iranian languages, while the languages of the culturally related Scythians and Sarmatians are counted among the north-east Iranian languages. Because Iranian languages were still similar in pre-Christian times, some researchers assume a dialect continuum (i.e. regionally related dialects) between what is now southern Russia / Ukraine up to the 2nd century BC. Scythian nomads and the Saks living in BC, with the younger tribal confederation of the Sarmatians, which started in the 4th century BC. The older Scythians ousted or integrated. In Iranian studies there is a researcher opinion that some south-east Iranian mountain languages in the Pamir , especially the languages Sariqoli and Wakhi spoken by the Tajiks of China in the autonomous district of Taxkorgan , could go back to remnants of Saki , but it is difficult to determine whether they are directly from Saki or related dialects emerged.

Sakian nomad archeology: settlement area and culture

The Saks nomadized in today's Kazak steppe between the Aral Sea , the area on both sides of the Tianshan Mountains and western China, including Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan . In contrast to most Scythians in Europe , who used a headgear similar to the Phrygian hat , some of the Saks wore pointed felt hats , which is why they were called pointed Scythians by many ancient authors .

Archeology associates them with the Issyk-Beschsatyr culture . The nomadic way of life and economy, the cult of the dead in the Kurgan and material culture have a lot in common with other tribes of the Scythian world between Siberia and the Black Sea region. Excavation finds in their context date to the 7th / 6th centuries. Century BC Chr.

While most of the burial rites and archaeological features of the Saks are very similar to other Scythian nomad groups (South Russian-Ukrainian Scythians , Sarmatians , massagers and contemporary archaeological cultures in the Altai and the surrounding area), right down to the common animal style , bronze kettles with a high beach foot used in rituals are obviously a specialty of the Saken and the Altai region. These bronze cauldrons, later spread throughout the steppe region from the time of the Huns , were only very common in the graves of Central Asian saks and the Altai region during the Scythian period, but were virtually unknown in massage-table, Sarmatian and West Scythian graves.

Along the Syrdarja , parts of the Saks were also settled due to sufficient arable land (towns, villages) and left better-developed tombs (e.g. the dome grave of Balandy). Apparently there was a certain coexistence of sedentary people and nomads (see also Pamiris ).

Their immediate neighbors were the north of Jaxartes nomadic Massagetae , the Greek authors were able to meet both strains no significant distinction. Further, by Herodotus the issedones called further the Argippaioi whose localization is problematic. According to Greek tradition, the Scythians of the Black Sea region also came from the east. Furthermore, the settled Bactrians and Gandhians were their southern and eastern settled neighbors.

The Afghan gold treasure from Tilla Tepe is attributed to Sakian nomads, most likely Saks in the narrower sense, perhaps also to Yuezhi .

history

Sakian population in the Tarim Basin

The exact date of the first historically established appearance of Saken in the east, especially in the western parts of the Tarim basin , is controversial, but it can be traced back to the 7th century BC. BC the presence of the Saks in western China, later in their own kingdom of Khotan (1st – 11th centuries AD). The earliest evidence of their presence in the Tarim Basin was unearthed in Jumbulak Kum (Chinese: Yuansha), the oldest Saki graves from the 7th century BC. Come from BC. The presence of the Saks in the wider area has been around since the 8th century BC. Has been proven ( Alagou graves , Ujgarak etc.). In Hotan and Tumxuk, the Saki language developed into the dominant language of the settled and urban populations through settlement, which is why all the surviving Saki texts come from this region.

The Chinese tradition since the 2nd century BC. Chr. Designates the Saks as sai (Old and Middle Chinese pronunciation: sək ).

Saks in Persian and Greek sources from the 6th to 4th centuries. Century BC Chr.

The Massagetae - Confederation and the Saken, most recently Queen Sparetra led battled the expanding empire of the Persian Achaemenids . According to various traditions, Cyrus II is said to have been in a campaign against the massage queen Tomyris around 530 BC. Have been killed. However, the Saks are also represented as Persian auxiliaries and, at the time of Darius I, as tribute-bearers .

Old Persian inscriptions from the 6th – 4th centuries Century name three groups of the Saks:

- the Sakā Paradraya ("Saken Behind-the-Seas") probably identical with the southern Russian-Ukrainian Scythians and Sarmatians by Greek authors north of the Black and Caspian Sea,

- the Sakā Tigraxaudā ("Saken Spitz-Huter" - after the pointed hat), they are localized in research in the Kazak steppes and in the fertile areas of Southeast Kazakhstan ( Seven Rivers ),

- the Sakā Haumawargā (named after the old religious drug Hauma , although the second part of the word has not been clarified beyond doubt), they are localized as nomads and partially settled people in the triangle between Tashkent , Dushanbe and Samarkand , perhaps also as far as Merw .

This subdivision is an external attribution by the Persians according to geographical and conspicuous cultural criteria and does not allow any conclusions to be drawn that these Saki groups understood themselves as uniform tribal associations, according to the numerous tribal lists in Greek sources most likely not.

Saken in Hellenistic times 4. – 1. Century BC Chr.

Alexander the Great had to face difficult battles with the saks and massagers who came to the aid of the Sogder Spitamenes from the steppe (329–327 BC).

The pressure of the Yuezhi , who had been driven out by the Xiongnu , divided the Saks fleeing from them into two groups. One group emigrated around 139 BC. In the border area of today's Afghanistan and Iran . This border region of Sistan got its name from the earlier name Sakastana (= land of the Saks), because it was shaped by the Sakian immigrants until the post-Christian era. The other group apparently fled a few years later via the Pamir and Hindu Kush to Gandhara and Punjab in northwest India. The backward tribal associations of the Sakah steppe nomads in Central Asia were assimilated into younger tribal associations and disappeared from history.

Under the Greek rule of the Greco-Bactrian Empire and later through contact in India in the 4th – 1st centuries. Century BC Many Saaks also adopted Hellenistic cultural elements. Among the numerous Hellenistic remains in the Central Asian regions of Bactria and Sogdia , for example, the gold treasure of Tilla Tepe , which, among other elements, also includes depictions of several Greek deities ( Aphrodite , Eros , Athene , Ariane , Dionysus ), undoubtedly does not belong to the long-established, settled population , but assigned to the nomads, the Saken or Yuezhi. From the 1st century BC In India, numerous representations of Greek gods on coins of Sak rulers and reliefs of Saks in Hellenistic cults point to the establishment of Hellenism.

Indo – Sakian (Indo – Scythian) Empire 2./1. Century BC Chr.–1./4. Century AD

Due to poor sources, the history of the Indo-Sakian Empire (also often called the Indo-Scythian Empire in Western ancient historical literature) is only limited based on the evaluation and circulation of its ruler coins, some inscriptions and archaeological remains and information in outer, mostly Greek and neighboring Indian ones Sources can be reconstructed. The dating of the rulers in particular remains controversial.

The Indo-Sakian Empire, like the Indo-Greek Empire that it had replaced , was not a centralized state. In some regions the rule of regional partial kings was tolerated, referred to in Persian and Greek inscriptions as satrap (governor), in inscriptions in Indian languages simultaneously as raino or raja (king), at the head of which was the Saki "king of kings". Due to some common coins and inscriptions of the king and the partial kings, it is certain that they (in many cases) were not independent or rebellious rulers. Among these partial kings in Punjab , East Kashmir and Rajasthan were rulers of Indo-Greek origin (in Indian sources yona or yavana , from Old Persian yauna = Greek / Ionian ) from the previous Indo-Greek empire. The two most important partial kings of the empire, however, were also of Sakian origin ( śaka in Indian sources , Anglicized shaka = Saken): the Northern Satraps , who ruled parts of Punjab and the Upper Ganges Valley, with the residence in Mathura and the Western Satraps , the parts of today's Gujarat , Rajasthan, Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh , with residence in Ujjain . In later centuries, yona / yavana and śaka families increasingly bore Indian names and culturally integrated into the regional Indian kshatriyas , the caste of warriors and rulers.

The first Indo-Sakian king Maues (reigned after an uncertain date perhaps 120–85 / 80 BC) was the leader of the Gandhara Saks. According to evidence - an inscription about the immigration of the Saks with his name in the Gilgit area and the mention of a sai king north of the Pamir with a similar name in Chinese sources - he might have led the escape of these Saks and had been a Sake king in the north . In some cases, in cooperation with Indo-Greek regional kings, he extended his domain from Hazara to Kashmir and resided in Taxila .

The Sakastana / Sistan came at the same time under the suzerainty of the Parthian Empire under Mithridates II (ruled 123-88 BC), with whom they allied. Under this influence, their leaders, the Vonones and Spalahores brothers (ruled perhaps 85-65 BC) and the son of the second, Spalagdames, bore Parthian names. They resided in Sigal in Sistan, but seem to have shaken off Parthian sovereignty and expanded their domain to the east, but how far is difficult to clarify due to the appearance of several other regional kings in the east. It is possible that Azes I (approx. 58 / 50–35 / 27 BC) from the Vonones family united the empire from Sistan to the Ganges and the coast, which he led to the zenith of his power, a new era in the empire (the "Vicrama era", beginning 58/57 or 43 BC) and moved the capital from Sigal back to Taxila. According to the Indian historical work Yuga Purāna , a few decades after the Indo-Greeks, the Indo-Saks also conquered large parts of the Ganges Valley and made Pataliputra the new capital, which is confirmed by inscriptions. It is not clear when this campaign took place, nor when parts of western India fell to the Saks. The western satraps are only detectable there a few years before the turn of the ages in the decay of the empire. Greek sources ( Periplus Maris Erythraei , Isidoros von Charax and Claudius Ptolemy ) also describe another capital of the Indian "Scythians", Minnagara , which was probably (but not yet identified) in the Sindh region on the lower Indus it is clear whether it was a temporary capital of the central empire, the western satraps, or some other part of the empire.

After Azes I, the empire seems to have got into crisis. Azilises's successor was probably initially a part-king in the Hazara region or co-regent of Azes, who later could probably only extend his rule to the central Indus. His successor Azes II. (Approx. 35-12 BC) lost areas on the lower Indus, but expanded in the Hindu Kush area. After that, several partial kings and the western and northern satraps seem to have made themselves independent. A new king of Sistan, Gondophares (ruled from approx. 19–45 AD) and his descendants used the rivalries to expand into the Indus Valley, but not beyond. Despite its origins from Sistan, this dynasty is distinguished in more recent literature as the Indo-Parthian Kingdom from the Indo-Sakan dynasties for three reasons : 1. Their coins and architectural remains followed the Parthian style, while the Indo-Saqs particularly adhered to their core regions Hellenistic models oriented, even relief images of the Indo-Parthian upper class have Parthian clothing, 2. the evaluation of an inscription from Gondophares by Ernst Herzfeld showed that the founder of the dynasty did not come from a Sakian family, but from the House of the Suras , one of the Parthian princely families , which is why 3. It is unclear whether the Indo-Parthian Empire could have been a vassal state of the Parthian Empire because of the relationship between the Suras and the Parthian royal house of the Arsacids . Shortly after the Indo-Parthian expansion under Gondophares, a victory inscription of the central Indian Satavahana empire prides itself on having conquered the royal city of Pataliputra from the śaka .

After this end of the central empire, there were several Indo-Greek (the last under Straton II until approx. 10 AD in Punjab) and Indo-Sakan empires in the area between the Indo-Parthian and Satavahana empires , some of which were temporary sought supremacy over the others, such as the Apracha rajas in western Gandhara with their center in Bajaur (Vijayamitra and successor), the Sakian satraps of Kashmir and Taxila with the neighboring region of Chukhsa to the west ( Liaka Kusulaka , his likely successor Zeionises (Jihonika) and others ) and after the Indo-Parthian conquest of the two countries, the northern satraps (Rajuvula, his son Sodasa and others) in Mathura. The expansion of the Kushana empire , which emerged from the Central Asian Yuezhi, led to the conquest of the Indo-Parthian and Indo-Saki empires in northern India at the end of the 1st / beginning of the 2nd century AD. Some of them continued to exist for a few decades as vassals of the Kushana Empire, but then disappeared from history.

Only the empire of the Saki Western Satraps with capital Ujjain (end of 1st century BC / beginning of 1st century AD – end of 4th century AD) remained, possibly initially as vassals of Kushana, but what is controversial, but later independent. This realm was involved in undecided existential conflicts with the Satavahana realm for a long time (beginning of the 1st century – beginning of the 3rd century), in which the western satraps finally asserted themselves and conquered large northwestern core regions from the Satavahana realm, which then disintegrated. Like the early Indo-Saks and Indo-Greeks, the 27 traditional western satrap rulers also tended to Buddhism, later satraps also promoted Brahmanic Hinduism. Obviously parts of the North Indian Indo-Sakian and Indo-Greek ruling class emigrated to the realm of the western satraps after the Kushana conquest. In addition to the all-Indian Brahmi script , the Kharoshthi script, which was widespread in Gandhara and East Central Asia, and a corrupt Greek script were used in the empire , but only to write Indian languages ( Sanskrit and Prakrit languages, especially Pali ). Several dedicatory inscriptions on Buddhist and Hindu temples come from private individuals who refer to themselves as yavana or śaka . However, because they only had Indian names and were written in Indian languages, these self-designations probably only came from family and social origins, especially in later times, and there is no evidence that Sakian or Greek was still spoken in the West Indies in the late satrap period. The fact that the western satraps, like the northern satraps in the upper Ganges region before, were the first to establish the Graeco-Buddhist Gandhara art in the West Indian Deccan region also speaks for a more numerous immigration from the north , followed by the later Hephthalites ("White Huns", in Indian sources hunas ). In sources from neighboring Indian empires, the western satrap empire is referred to as the "empire of the śaka" and its reign is considered in western Indian historiography to this day as the Śaka epoch / Śaka era, which begins here in the 1st century AD. Ultimately, the empire of the western satraps was conquered around 397 by the ruler of the neighboring Gupta empire , Chandragupta II , ending the last political legacy of the Indo-Scythian (Indo-Sakian) epoch.

aftermath

The Scythian and Parthian tribes represent the heroes of the Iranians in Firdausi's Shāhnāme , in particular the Indo-Parthian Rostam and Princess Rudabeh from Kabulistan are praised in the work.

See also

literature

- Gavin Hambly (Ed.): Central Asia (= Fischer Weltgeschichte . Volume 16). Fischer paperback, Frankfurt am Main 1966.

- Hermann Parzinger : The Scythians. CH Beck Wissen, CH Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-50842-1 .

- RC Senior: Indo-Scythian Dynasty . In: Ehsan Yarshater (Ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica , as of: July 20, 2005, accessed on June 5, 2011 (English, including references)

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ Jürgen Paul : New Fischer World History. 2012. Volume 10: Central Asia, pp. 57–58: "The fact that many of them spoke Iranian languages should not go unmentioned, but it is certain that the cultural characteristics are also represented by other ethnic-linguistic groups. It is not It is very clear whether the Scythian Confederation did not also include groups ... which, for example, did not speak an Iranian language. "

- ↑ Yu Taishan: The Name “Sakā”. in: Sino-Platonic Papers. No. 251 (Aug 2014), Philadelphia.

- ^ Victor Mair & Prods Oktor Skjævø: Chinese Turkestan II. In Pre-Islamic Times . in: Encyclopædia Iranica , eighth paragraph.

- ↑ James Patrick Mallory : Bronze Age Languages of the Tarim Basin , p. 46.

- ^ Victor Mair & Prods Oktor Skjævø: Chinese Turkestan II. In Pre-Islamic Times . in: Encyclopædia Iranica , eighth paragraph; James Patrick Mallory : Bronze Age Languages of the Tarim Basin.

- ^ Hermann Parzinger : The early peoples of Eurasia: from the Neolithic to the Middle Ages. Munich 2006, pp. 660-661.

- ^ Victor Mair & Prods Oktor Skjævø: Chinese Turkestan II. In Pre-Islamic Times . in: Encyclopædia Iranica , Chapter: Iranians in the Tarim basin .

- ↑ Hiroshi Kumamoto: Khotan II. Pre-Islamic History . in: Encyclopædia Iranica .

- ↑ Prods Oktor Skjærvø: Khotan . in: Encyclopædia Iranica .

- ↑ Rüdiger Schmitt : HAUMAVARGĀ . In: Ehsan Yarshater (Ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica , as of December 15, 2003, accessed on June 5, 2011 (English, including references)

- ^ Laurianne Martinez-Sève: Hellenism in: Encyclopædia Iranica , section The Greco-Bactrians and their succcessors.

- ↑ Osmund Bopearachchi: Indo-Greek Dynasty in: Encyclopædia Iranica .

- ^ RC Senior: Indo-Scythian Dynasty . in: Encyclopædia Iranica , 1. – 13. Paragraph.

- ↑ Pierfrancesco Callieri: Sakas: In Afghanistan . in: Encyclopædia Iranica .

- ^ RC Senior: Indo-Scythian Dynasty . in: Encyclopædia Iranica , 13. – 16. Paragraph.

- ↑ Cf. DW Mac Dowell: Azes in: Encyclopædia Iranica .

- ^ ADH Bivar: Gondophares in: Encyclopædia Iranica .

- ↑ Osmund Bopearachchi: Jihoņika in: Encyclopædia Iranica .

- ^ Pia Brancaccio: The Buddhist Caves of Aurangabad. Transformation in Art and Religion. Leiden 2011, pp. 106-107 (with footnote 77).