Maues

Maues ( handed down on coins as genitive ΜΑΥΟΥ Mauou , in Kharoshthi as Moasa) was an Indo-Scythian king who lived around 120–85 BC. BC (according to other investigations 85-60 BC) ruled.

Around 145 BC BC peoples who are referred to by ancient sources as Scythians invaded Bactria (in the north of present-day Afghanistan ) and India. They destroyed the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom and represented a threat to the Indo-Greek Kingdom (in the north of what is now Pakistan ). After a few decades, an empire of its own was founded. Maues is considered the founder and most important ruler of this Indo-Scythian dynasty.

Dating

The exact chronological classification of Maues is not certain, but it seems that the first quarter of the first century BC Most likely. There are some dated inscriptions that mention Maues. There is a copper plaque from Taxila from a certain Patika that relates to Buddhist relics. This inscription is dated to the year 78, the fifth day of the Macedonian month of Panemus , and names the Great King, the great Moga . The date is problematic as it is not certain which era it refers to. It is often assumed that it was an era founded by Maues, which is only attested here. The identification of Maues (in Greek inscriptions) with the Moga of the inscription on the copper plate (in Kharoshthi) is not entirely undisputed in research. Other dated inscriptions on the Mau state the dates 58, 60 and 68. Maues minted the coins of some other rulers. The coins of the Indo-Greek king Apollodotus II , who was probably the predecessor of Maues in Taxila, deserve mention here.

Rule and family

The assumption of power by the Wall has not yet been clarified with absolute certainty. The sites and mints of his coins give an indication of his territory, which included Hazara, Kashmir , Gandhara with the capital Taxila and parts of Afghanistan. It is also attested by an inscription at Chilas ( Gilgit-Baltistan , in the far north of Pakistan). This inscription also names the satrap Ghoshamitra. A second inscription names the ruler in connection with the construction of a building and names the satrap Sidhalaka. It can be assumed that he conquered parts of the Indo-Greek Empire and led an aggressive policy of conquest. However, the events remain largely in the dark. Attempts at reconstruction are largely based on coins.

After the coinage, Taxila may have been its capital. Perhaps he took over the title of King of Kings directly from the Parthians . The title is attested on his later coinage. It has therefore also been assumed that he was of Parthian descent. Names and deities (mostly Greek) on the coins indicate a marriage policy with the Indo-Greeks. A woman named Machene , who may have come from Taxila, appears on some coins . Her position is controversial, mostly she is seen as the wife of the Maues, others see her as his mother. King Artemidoros describes himself on some coins as the son of the Maues. He may have been either a birth son or a vassal . Before these coins of Artemidoros became known, the latter was generally regarded as the Indo-Greek king.

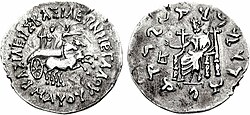

The coins of the Maues

The coins of the Mau never show the head of the ruler, but are generally based on Indo-Greek coins, such as that of Apollodotus II. Legends in Kharoshthi can be found on the reverse, while the obverse has Greek inscriptions.

From the area of Hazara and Kashmir come coins with a city goddess on one side and Zeus on the other. There are also coins from Kashmir that show the ruler on a horse or with non-Greek deities.

Silver coins showing Zeus and Nike come from Taxila. Animals such as bulls and elephants, as well as Greek deities appear on bronze coins. Copies of coins from Demetrios I were also issued here.

In the northwest region there are silver coins with an Artemis and a chariot with Zeus. Some drachmas are square and depict Zeus, Nike, or a moon deity. Finally, there are imprints with motifs that have been interpreted as Buddhist. Coins with a seated figure that resembles later representations of the Buddha should be mentioned here. In the absence of clear legends, however, this interpretation is uncertain.

literature

- Baij N. Puri: The Sakas and Indo-Parthians. In: János Harmatta, Baij N. Puri, GF Etemadi (ed.): History of civilizations of Central Asia. Volume 2: The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 BC to AD 250. UNESCO, Paris 1994, ISBN 92-3-102846-4 , pp. 191-207.

- Robert C. Senior: Indo-Scythian Dynasty . In: Ehsan Yarshater (Ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica , as of: July 20, 2005, accessed on June 5, 2011 (English, including references)

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Baij N. Puri: The Sakas and Indo-Parthians. In: Harmatta et al. (Ed.): History of civilizations of Central Asia. Volume 2. 1994, pp. 191-207, here p. 193.

- ^ William W. Tarn : The Greeks in Bactria & India. 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1951, pp. 494-502.

- ↑ The Minor Indo-Parthian Eras on kushan.org, accessed June 5, 2011 (English)

- ^ William W. Tarn: The Greeks in Bactria & India. 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1951, p. 496, n.4.

- ↑ Ahmad Hasan Dani: Chilas. The City of Nanga Parvat (Dyamar). Ahmad Hasan Dani, Islamabad 1983, pp. 99, 100, 102.

- ↑ Ahmad Hasan Dani: Chilas. The City of Nanga Parvat (Dyamar). Ahmad Hasan Dani, Islamabad 1983, pp. 109, 110.

- ↑ Baij N. Puri: The Sakas and Indo-Parthians. In: Harmatta et al. (Ed.): History of civilizations of Central Asia. Volume 2. 1994, pp. 191-207, here p. 194

- ^ Robert C. Senior: Indo-Scythian Coins and History. Volume 1: An Analysis of the Coinage. Chameleon Press, London et al. 2001, ISBN 0-9636738-8-2 , 27-28.

- ^ A b c Robert C. Senior: Indo-Scythian Dynasty . In: Ehsan Yarshater (Ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica , as of: July 20, 2005, accessed on June 5, 2011 (English, including references)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Maues |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Moasa (kharoshthi) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Indian king |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 2nd century BC Chr. |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1st century BC Chr. |