Tilla Tepe

Tilla Tepe ( Persian طلا تپه; also Tillya Tepe or Tillja Tepe , the golden hill) is a hill in northern Afghanistan . In 1978 six graves were found there during excavations, which date to the time around the birth of Christ. They contained more than 20,000 pieces of jewelry, weapons and garments, most of which consist of gold and semi-precious stones. The find is also known as " Bactrian gold ". It is one of the most important archaeological finds of the 20th century. Because of the Afghan war , the treasure was lost. However, it was secured in 2004 and has been preserved in full.

Geographical location

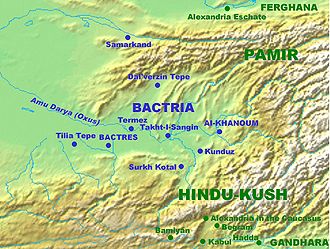

Tilla Tepe is located in the Scheberghan oasis in northern Afghanistan, in the Juzdschan province . To the west is the city of Scheberghan and about 100 kilometers to the east is Baktra , the capital of ancient Bactria. The oasis is irrigated by the Safid-Rud and Siyad-Rud rivers , which enables agriculture. About 500 meters north of Tilla Tepe are the ruins of Yemschi Tepe , a circular city that probably flourished in the first centuries after the birth of Christ, but is probably an older foundation. Tilla Tepe itself is a small hill about three to four meters high with a diameter of about 100 meters, which is the only elevation in the otherwise flat landscape.

History of the region at that time

Until about 135 BC The region of Bactria belonged to the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. Then it came under the rule of the Saken and Yuezhi , who invaded the area as conquerors from southern Siberia and Mongolia. They plundered and destroyed numerous cities and destroyed the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. These nomads, who are counted among the Scythians by some research , eventually settled in Bactria and adopted an urban way of life. In the following time, the area seems to have belonged to the Parthian sphere of influence, although the eastern extent of the Parthian Empire is disputed in research. Little is known about the period after the fall of the Greco-Bactrian Empire, which is why it is considered the dark age of Central Asia. Thereafter, the area came under the control of the Kuschana , a clan of the Yuezhi, who managed to unite the Yuezhi tribes under the empire they founded shortly after the birth of Christ under Kujula Kadphises . The tombs of Tilla Tepe probably date to a time shortly before the emergence of the Kushan Empire, when the Yuezhi or Saks ruled Bactria.

Discovery and history of the finds

Since 1969, a Soviet-Afghan team of archaeologists led by Viktor Ivanovich Sarianidi has been digging at various locations in northern Afghanistan, a region that had been virtually unexplored until then, and was mainly devoted to Bronze Age sites. The oasis culture was discovered.

In 1978, excavations began at the Tilla Tepe hill, located about 500 meters south of the ancient city ruins of Yemschi Tepe, after a brief excavation in 1970. Here a village first came to light that dates back to the third century BC. Dated. A fortified temple was found under this village, probably dating back to shortly before 1000 BC. Is to be dated. A grave came to light in this complex in November 1978, which attracted attention mainly because of its rich gold finds. By February 1979 six graves, all richly decorated with gold, had been uncovered. Because of the troubled political situation, the excavation team had to leave the country, and the excavations at the site could never be continued.

The finds reached the National Museum in Kabul in 1979 , at a time when there was already unrest in Afghanistan. Due to the politically insecure situation in the country, most of the treasures were kept in safe custody in the following years. Only in 1980 and 1991 were small parts of the collection temporarily exhibited. During the Soviet occupation of the Afghanistan conflict, the finds were stored in the museum in Kabul with a one-year break. After the withdrawal of the Soviet armed forces, at the end of 1989 they were deposited together with some other museum holdings in the basement of the central bank located in the presidential palace. The museum itself was severely damaged in the civil war after the Soviet withdrawal in the years that followed, in some cases severely through fighting and was also plundered or vandalized several times. There were rumors that the treasure had been confiscated by the Soviet Union or otherwise stolen. After the fall of the Taliban, many of the country's art treasures were lost in the chaos of war. Even with the finds from Tilla Tepe it was believed that they would probably be gone forever.

It was not until 2003 that the museum holdings stored in the central bank were found again, although, due to bureaucratic delays, it should take until April 2004 before the safes could be opened in the presence of Sarianidi and the finds could be secured. It turned out that the collection, including every single little thing, was complete.

Since 2007 the most important grave finds have been on an exhibition tour through Europe, the USA and Canada. In 1985 a volume with many color photographs was published, translated into various languages, presenting the most important finds. In 1989 a scientific publication appeared on the excavations. A complete excavation publication is still pending.

The fortress

A fortress was built shortly before 1000 BC. Built on a small hill. The building stood on a four meter high and 100 meter wide base that was partially embedded in the ground. The fortress was almost square and had four rounded corner towers and semicircular towers. The entrance was in the north. In the middle of the fortress stood a kind of hall, which is also interpreted as a temple. The main find material is ceramics, although there were undecorated vessels, but also those that were painted with geometric patterns. Some of the pottery was made on a potter's wheel. The handmade ceramics are mostly simple consumer goods.

In addition to the ceramics, there are some bronze knives and arrowheads. The place seems to have been inhabited for a long time without it being possible to give exact dates. Culturally, this fortress can be linked to other archaeological sites in Central Asia, with Tilla Tepe being the best-researched site. The culture found here belongs to the time after the fall of the oasis culture of Central Asia. It is known as the period of the Barbarian Occupation .

Burials and burials

After the fortress, perhaps around 800 BC. BC, was abandoned, the place was around 400 BC. Colonized again. A small village emerged, but it was not inhabited for long. Shortly after the birth of Christ, the square was used as a cemetery. The six graves found were pits that were covered with wooden planks and formed a cavity. The dead lay in wooden coffins that had no lids but were probably wrapped in blankets. The buried are buried on their backs in costly robes adorned with gold and with rich jewelry. A few other additions, such as vessels, mirrors or cosmetic utensils, were found in and next to the coffins. There are no indications that there were burial mounds, but the hill of the castle ruins may have served as a burial mound. The burials belong to five women and one man. At the time of her death, the fortress on the hill was already in ruins and the graves were partially dug into the old walls.

Identity of the dead

There is much to suggest that nomads or former nomads were buried here. The type of robes (trousers) and some weapons, such as two bows in the man's burial, are typical of nomadic peoples. A foldable and therefore easily transportable crown (grave 6) can also be seen in this context. However, it was not possible to precisely determine which ethnic group the buried people belonged to. On the one hand, the Yuezhi, who, according to Chinese sources, consisted of various clans and invaded the region, on the other hand, could have been saks who belong to the Scythian culture. They invaded Bactria at about the same time as the Yuezhi, although they tended to settle in the Hindu Kush region further south and in southern Afghanistan. The rich decoration of the tombs with golden plaques on the robes, gilded hoods and many other gold gifts is indeed very similar to other well-known Scythian burials that could be found on the Black Sea, for example.

On the other hand, indications that indicate belonging to the Yuezhi are the discovery of a coin from King Heraios , who is counted among this nomadic people. In addition, many grave goods show stylistic similarities with the work of the Siberian animal style from Siberia and Mongolia, where the Yuezhi came from. The archaeologist Sarianidi therefore even saw the buried as early rulers of the Kushana, who were indeed a Yuezhi clan. Others, on the other hand, see them as saks who were under Parthian rule. The more recent research is more cautious. She tends to classify the buried as saks because of the similarities already described, but at the same time she also wonders whether these popular names from historical works are even relevant for Tilla Tepe. These names come from ancient Chinese and Greco-Roman works, the authors of which were not on site and their information only obtained from second or third hand.

It is noticeable that the man was buried in the middle and the women around him. A local leader may have been buried here, whom his wives followed or had to follow to their death. This ruler may have had his seat in the neighboring city of Yemschi Tepe . It is also possible that they were pure nomads who deliberately allowed themselves to be buried at some distance from the city.

The grave goods

Three groups of finds can be distinguished.

- Imported pieces, including Roman and Parthian coins, an Indian medallion, two Chinese silver mirrors, an Indian ivory comb and Roman glasses. However, only a few such objects have been found.

- Objects that obviously come from the Greco-Bactrian period. These include a cameo with the image of a man, in style very similar to the Bactrian coins, and the gold statuette of a ram from grave 4, the base of which indicates that it originally served a different purpose and was only used as an element of clothing in the grave.

- However, the majority of the finds seem to come from the culture of those buried here, and these objects show a remarkable synthesis of various stylistic features. Various influences can be observed here:

- A sub-group are works of local tradition, the origins of which can be traced back to the Bactrian Bronze Age. Here is a crown that is made of gold leaf and represents a stylized tree. Such crowns are known from the Scythian area. The Parthian, Greco-Bactrian or Kushana rulers, on the other hand, did not wear crowns, but tiaras . The tree motif is well documented in the Bactrian Bronze Age.

- There are clasps that represent the erots and which one would initially assign to the Hellenistic area. However, they have crescent figures on their foreheads. Lunar symbols were very popular in Bactria and the Middle East.

- There are gold clips with erotes that ride fish (instead of dolphins, as would be common in the Hellenistic art repertoire). A golden sheath is decorated with dragons and shows strong Siberian, Iranian and Indian influence.

- The weapons from the man's burial show a mixture of Bactrian, Siberian, Iranian and Indian style elements. On a scabbard you can find winged griffins, dragons and big cats, which are shown in a row. On a second sheath there are two winged dragons, one of which has bitten into the leg of the other.

- The motifs on two shoe racks that show a man in a car are taken from Mongolia or the Chinese cultural area. The chariot is pulled by a griffin, which again is not known from China, where there are always horses. Griffins are popular motifs from the Bactrian Bronze Age.

- Finger rings with the representations of Greek deities and Greek inscriptions are certainly local works. Some of the figures look a bit clumsy. The accessories of these figures are often not known from the Greek region, for example a Nike is holding a staff or a man is shown with a dolphin.

Clothes and weapons

Gold plating was found on the skeletons, which once adorned the clothing. However, since almost no textiles have survived in the graves, it is often difficult to determine the function of individual objects. Rows of small gold plating were certainly part of clothing. But it is not always certain whether the hems or middle parts were decorated. The dead also wore several pieces of clothing on top of each other, so that it is difficult to assign certain decorations to a costume. With all caution, it can be assumed that the man was wearing a short jacket and a caftan . He wore wide trousers, which are known from Parthian representations and from those of the Kushana rulers.

The robes and especially the jewelry of the women differed considerably. They may therefore belong to different tribes and social classes. It was assumed that the young woman from grave 5 was childless, as it is the poorest of the women's burials. After all, it can be said with certainty that they all wore a robe, namely a tunic over their trousers. This is a garment that is still worn today by women in this area.

The man's weapons (two bows, a long sword, dagger and knife) are typical of nomads. They were placed close to the thighs so as not to obstruct a rider while riding. However, this does not mean that those buried here were actually nomads. It may be nomadic traditions that are reflected in the costume custom, while the buried had long been settled.

Dating

The historical and cultural classification of the graves of Tilla Tepe is difficult, as comparative finds are rare and often cannot be dated, and the chronology of the region generally causes difficulties. It is believed that the graves were all dug around the same time, as the grave goods are similar in style. The main stop for dating is five coins. Three of them belong to the Parthian culture. From grave 3 comes a silver coin from Mithridates II. (123-88 BC) and from grave 6 the copy in gold of a coin from Gotarzes I (95-90 BC). In grave 1 the dead woman was holding a coin from Heraios , who probably ruled in this area shortly after the birth of Christ.

The most recent coin shows the Roman Emperor Tiberius and was minted in Gaul between 16 and 37 AD. It comes from grave 6, where the coin of Gotarzes I was about 100 years older. In general, care should be taken when dating with coins, as these coins could have been in circulation long before they were placed in the graves. The graves were probably dug around these years, which is assumed due to the lack of more recent coinage. The burials therefore date to the time after the fall of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom and the time before the Cushan empire came into being, probably in the first decades after the birth of Christ.

Description of the individual burials

Grave 1

Tomb 1 was on the west side of the hill and was the first to be discovered. A woman around 20 to 30 years old was buried in this burial. It was a 2.5 by 1.3 meter large and 2 meter deep pit in which the woman was placed on her back. Her head was decorated with seven small (4.1 × 2.9 cm) gold plaques depicting a man with serpent legs holding a dolphin around his neck. These plaques may once have been hair ornaments, but they may also have been cushions on a long-forgotten headgear. She was wearing earrings. There were more gold plaques around the shoulder, indicating that the dead woman once wore a scarf. The sleeves of her robe were also richly decorated. There were gold inlaid with turquoise and those made of the same materials that apparently show small groups of leaves. The dead woman held a coin in her hand. A silver cosmetic container was found as a grave gift.

Grave 2

Grave 2 was behind the north wall of the temple and formed a 3 x 1.6 m pit about 2 m deep. The dead woman was buried in a coffin that was 2.2 m long, had no lid and stood on wooden supports. The discovery of silver and gold round disks suggests that the coffin was once covered with or wrapped in a blanket that was decorated with this. The corpse was facing north. The person buried was a woman in her thirties or forties. She was lying on her back. Numerous plaques suggest that she once wore a high cap. Probably as earrings she wore two pieces of gold jewelry that show a man between two dragons and are richly inlaid with semi-precious stones. Two other tags that were found on the head may have been attached to the cap. The dead woman wore different rings, two of which depict the Greek goddess Athena . A Greek inscription on one of the rings confirms this identification. Two gold bracelets have ends with antelope heads; two leg rings are undecorated and also made of gold. A necklace is made up of large gold pearls, some of which show a pattern in their granulation . The end pieces are conical and again decorated with granulations. Various pieces of gold must have adorned the burial's clothes. There are a couple of erotes riding a fish. The grave goods also include numerous golden rams' heads, golden heart-shaped supports, tiered pyramids and round, flower-like supports. Two belt-like pieces of jewelry probably also adorned the robes of the dead. One of these consists of a series of golden disks held together by double-moon shaped pieces. A comparable piece is decorated with gold disks hanging on it. Amulets in the shape of hands or feet were also found near the dead woman.

Grave 3

The grave pit was 2.6 × 1.5 m in size and oriented north-south, with the burial almost at the highest point of the hill. The chamber was probably covered with a wooden ceiling, which in turn had a leather ceiling, which was decorated with gold discs. These golden discs could also come from a ceiling surrounding the coffin. The floor of the chamber had remains of matting. The coffin placed on top was about 2 m long, 64 cm wide and had a height of 40 to 50 cm. The burial chamber had been disturbed by intruding rodents who had taken many golden grave goods into their own building, so that they were spread over a wide area in the excavation area. Tilla Tepe is also known as the hill of gold , this may be due to the scattered additions from this grave. The buried woman was probably a woman who was buried lying on her back. Her head rested on a gold disc. She once wore a high cap, of which the gold edging was still preserved. The hairstyle also includes two golden hairpins with rosette-shaped heads. Her head was also adorned with a gold pendant with two horses as a motif. A Chinese silver mirror lay on her chest. Various gold work seems to have been part of her garment. Two golden clasps should be mentioned here, each showing a soldier in Hellenistic equipment. Two smaller clasps show erotes riding a stylized dolphin. As jewelry, she wore gold medallions with busts, gold bracelets that were not decorated any further, and a gold crescent moon with stylized pendants. One of two golden cosmetic jars bore a short Greek inscription indicating the weight of the jar (and therefore its value) in Ionic measurements. An ivory comb is an Indian work and is similar in style to the ivory carvings unearthed in Begam . The dead woman wore golden soles. It was accompanied by a gold coin of Tiberius , which is the oldest Roman coin found in Afghanistan. Another coin comes from the Parthian ruler Mithridates II. Other grave goods included a second mirror with a handle - although mirrors of Chinese origin have no handle -, a silver bowl, a silver vessel with a lid and a 39 cm high vessel with two handles.

Grave 4

The grave was in the middle of the western wall of the former temple. It was 2.7 m long, 1.3 m wide and 1.8 m deep. The burial was oriented north-south. The skeletal remains of a horse were found in the grave shaft, which may have been a funeral meal or a sacrifice. The dead man himself lay on his back with his head facing north in a wooden coffin (2.2 × 0.7 × 0.75 m) covered with red leather, which in turn was painted with white and red motifs, as well had gold plaques. The coffin itself stood on a wooden frame about 15 cm high. At the head end there were the remains of a chest with cosmetic utensils. The dead man was about 1.75 to 1.85 m tall, whose head rested on a golden bowl, which in turn rested on a silk pillow. The bowl bore the Greek inscription "CTA MA", which probably indicated its weight in Ionic measurements. The man wore a cap with a golden ram and a golden tree attached to it. He wore a gold chain with a cameo and a gold belt. The latter consisted of a wide, flexible golden ribbon and had nine golden medallions, each of which had a three-dimensional figure riding a panther. The representations are reminiscent of those of Dionysus . The robes of the deceased were richly decorated with gold plating. His shoes also had gold plating, especially two round attachments that show a man in a chariot pulled by a dragon. Both essays are made of gold and turquoise and show Chinese / Mongolian influence. Comparable shoe attachments are known from depictions from Palmyra . To his right the man carried a long iron sword and a dagger with a golden hilt. The sword was in a golden sheath. On his left he carried a golden sheath for three knives, one of which had an ivory handle. In this tomb there was also found a gold medallion depicting a lion and a man with a wheel. The inscriptions are in Kharoshthi . The lion and the wheel play a special role in Buddhism , so that it can be assumed that these are Buddhist motifs.

Grave 5

The grave was 2.05 × 2.10 × 0.8 meters in size and dug into a Persian clay ramp. There were no signs of a coffin, which was probably made of wood without metal parts. There were numerous silver plaques around the body, which are round or in the shape of grape leaves. Maybe they belonged to a cloth that was wrapped around the coffin. The dead woman was a young woman, no more than 20 years old. She was lying on her back with her head facing west. The most notable find was a collar made of gold and various semi-precious stones. The dead woman wore simple gold bracelets and leg rings. Gems, one with a griffin, the other with a Nike, were deposited next to the corpse. The grave goods included a mirror with a handle, two silver vessels and a bronze bell.

Grave 6

Grave 6 was in the western part of the fortress ruins. It was 3 x 2.5 m in size and about 2.5 m deep. A wooden coffin had once stood on brick supports. The coffin, like the others, probably had no lid, but was covered by a cloth that was decorated with gold plating. Next to the coffin was a depot with grave goods. The corpse is about a 20-year-old woman who was once about 1.52 m tall. It is noteworthy that her skull was deliberately deformed, a custom that can also be observed in other parts of Central Asia. Her head lay on a silver bowl and was adorned with an elaborate golden crown, which consists of five parts and was therefore collapsible and easier to transport. Various pieces of gold adorned the hair. Two pendants show the mistress of the animals , a woman standing between two mythical animals. The golden fasteners of her robe lay on her chest. They each show Dionysus and Ariadne riding on a griffin. A Nike flies behind them while the griffin kicks an enemy. The so-called Aphrodite of Bactria was probably also attached to the robe . It is a 5 cm high figure of a winged woman with a bare chest. Although the work is certainly Hellenistic in influence, the figure shows unhellenistic elements: the wings are relatively small, she wears bracelets and has a center parting. The dead woman wore a golden chain decorated with a flower motif, which is inlaid in turquoise. There were two pairs of gold arm and leg bracelets. The leg bracelets are plain and largely undecorated, the bracelets have lion heads. A gold coin that copied the Parthian coins from Gotarzes I should be mentioned as an addition . In the tomb there was also a Chinese silver mirror and another mirror with an ivory handle, a heavily worn Parthian silver coin, two Roman glasses, a ceramic vessel and two silver vessels. Some of these grave goods were outside the coffin.

Art historical significance

The pieces of jewelry from Tilla Tepe show a surprising variety of influences and style elements. There are Hellenistic motifs, but also other elements such as those from Siberia or the Mongolian region. Despite this cultural diversity, a large part of the jewelry from Tilla Tepe was produced in local Bactrian workshops, which suggests comparable gold work from Taxila .

The Hellenistic influence on the region was known for a long time through coinage, as found coins are shaped according to Hellenistic models and bear Greek inscriptions. Alexander the Great , when he was born in 329 and 328 BC Greeks settled in Bactria, imported Hellenism into the region, so to speak. The art of the subsequent Greek-Bactrian kingdom was largely Hellenistic, as the excavations in Ai Khanoum have shown. Around 135 BC This kingdom went under during the invasion of nomads. In the Hindu Kush and in Gandhara there were some Greco-Indian kings for more than a hundred years , but little is known about them apart from coin finds. The political history and art of Bactria in the following centuries is also largely uncertain, and this period is therefore referred to as the Dark Age .

The finds by Tilla Tepe, dated to the first decades after the birth of Christ, close an archaeological and art-historical research gap in the history of Central Asia. They form a link between the Greek art of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom and the Buddhist art of the later Kushana, which shows many Hellenistic features, and are therefore of particular importance. The gold work from Tilla Tepe in particular shows that there were workshops in Bactria that worked in the Hellenistic tradition after the fall of the Greco-Bactrian Empire.

The art of the Kushana, which appeared from around 50 AD, also shows many Hellenistic influences. Their empire was the center of Graeco Buddhism . The art and culture of this period are well known through extensive finds, even if there are still difficulties in dating certain monuments. The origin of these Hellenistic influences is however controversially discussed in research. Basically there were two views, namely on the one hand that their art was influenced by the art of the Roman Empire at that time, on the other hand one wondered whether Hellenistic traditions on site survived after the fall of the Greco-Bactrian Empire. A third possibility is to combine both theories. Graeco-Buddhist art had its origins in Greco-Bactrian art, but was also influenced by Roman art when trade relations with the Mediterranean were intensified in the Cushan Empire. The finds from Tilla Tepe, however, clearly show how strongly Hellenistic traditions were already alive in the region before the Kushana.

literature

- Viktor Iwanowich Sarianidi : Bactrian gold - from the excavations of the necropolis of Tillja-Tepe in northern Afghanistan . Leningrad 1985.

- Viktor Iwanowich Sarianidi: Bactrian Gold, from the Excavations of the Tillya-Tepe Necropolis in Northern Afghanistan. Leningrad 1985.

- Viktor Ivanovich Sarianidi: On the culture of the early Kusana . In: Jokob Ozols, Volker Thewalt (ed.): From the East of the Alexander Empire, peoples and cultures between Orient and Occident, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India . Cologne 1984, ISBN 3-7701-1571-6 , pp. 98-109.

- Viktor Ivanovich Sarianidi: The Art of Ancient Afghanistan. Leipzig 1986, ISBN 3-527-17561-X .

- VI Sarianidi, V. Schiltz: Ancient Bactria's Golden Hoard . In: Friedrik Hiebert, Pierre Cambon (Ed.). Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures from the National Museum, Kabul. National Geographic , Washington, DC 2008, ISBN 978-1-4262-0295-7 , pp. 211-293. (Book accompanying a special exhibition in the USA on ancient art from Afghanistan)

- Viktor Ivanovich Sarianidi: Khram i nekropolʹ Tilli︠a︡tepe. Moskva 1989, ISBN 5-02-009438-2 . (Summary in Russian with a detailed description of the temple and its finds; there are plans and drawings of the graves)

Web links

- Afghanistan - Hidden Treasures - Slide shows with audio commentary about Tilla Tepe, among others, on National Geographic Online (English)

- Afghanistan - Hidden Treasures - Burial sites - Additional data for Google Earth to be able to view Tilla Tepe in detail

- The Bactrian Gold I.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Elena Neva: Ancient Jewelry from Afghanistan. on artwis.com, March 12, 2008 ( Memento from February 18, 2015 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Viktor Sarianidi: The Art of Ancient Afghanistan. P. 326f.

- ↑ Marek J. Obrycht, In: Josef Wiesehöfer : The Parthian Empire and its testimonies. Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-515-07331-0 , pp. 26-27.

- ^ Willem Vogelsang: The Afghans. Oxford 2002, ISBN 0-631-19841-5 , pp. 141-142.

- ^ A b Carla Grissmann: The Kabul Museum: It's Turbulent Years. In: Juliette van Krieken-Pieters (Ed.): Art and Archeology of Afghanistan - Its Fall and Survival. Brill Academic Publishers, Leiden 2006, ISBN 90-04-15182-6 , pp. 63-71. ( Handbook of Oriental Studies. Section 8 Uralic & Central Asian Studies , Volume 14)

- ^ War confusion in Kabul - The Disappearance of the Treasure , on: ZDF website , broadcast on July 18, 2004, accessed on November 24, 2009

- ↑ Elena E. Kuz'mina; JP Mallory: The origin of the Indo-Iranians. Leiden, Boston 2007, ISBN 978-90-04-16054-5 , pp. 423-25.

- ↑ so Sarianidi: The Art of Ancient Afghanistan. 301

- ^ A b V. Schiltz: Ancient Bactria's Golden Hoard . In: Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures from the National Museum, Kabul , p. 231.

- ↑ a b c Sarianidi: On the culture of the early Kusana . In: Jokob Ozols, Volker Thewalt (ed.): From the East of the Alexander Empire, peoples and cultures between Orient and Occident, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India . Pp. 98-109.

- ↑ a b Sarianidi: The Art of Ancient Afghanistan. 301; Georgina Hermann, Joe Cribb (Eds.): After Alexander: Central Asia before Islam . Oxford 2007, ISBN 978-0-19-726384-6 , p. 55.

- ↑ Marek J. Obrycht, In: Josef Wiesehöfer (Ed.): The Parthian Empire and its Testimonies , Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-515-07331-0 , pp. 26-27.

- ↑ a b picture ( memento of April 7, 2010 in the Internet Archive ), accessed on November 18, 2009.

- ^ V. Schiltz: Coins and Dating the Tombs . In: Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures from the National Museum, Kabul . Pp. 225-227.

- ↑ V. Schiltz: Tillya Tepe, tomb I . In: Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures from the National Museum, Kabul . Pp. 232-240; Sarianidi: Bactrian Gold. Pp. 226-230; Sarianidi: Khram i nekropolʹ Tilli︠a︡tepe. Pp. 49-53.

- ↑ image , accessed on November 16, 2009.

- ↑ V. Schiltz: Tillya Tepe, tomb II . In: Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures from the National Museum, Kabul . Pp. 241-253; Sarianidi: Bactrian Gold. Pp. 230-236; Sarianidi: Khram i nekropolʹ Tilli︠a︡tepe. Pp. 53-66.

- ↑ V. Schiltz: Tillya Tepe, tomb III . In: Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures from the National Museum, Kabul . Pp. 254-264; Sarianidi: Bactrian Gold. Pp. 236-246; Sarianidi: Khram i nekropolʹ Tilli︠a︡tepe. Pp. 67-84.

- ↑ image , accessed on November 8, 2009

- ↑ Vesta Sarkhosh Curtis, Robert Hillenbrand, JM Rogers (ed.): The art and archeology of ancient Persia: new light on the Parthian and Sasanian empires . London 1998, ISBN 1-86064-045-1 , p. 23.

- ↑ V. Schiltz: Tillya Tepe, tomb IV , in: Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures from the National Museum, Kabul . Pp. 265-279; Sarianidi: Bactrian Gold. Pp. 246-251; Sarianidi: Khram i nekropolʹ Tilli︠a︡tepe. Pp. 84-110.

- ↑ V. Schiltz: Tillya Tepe, tomb V . In: Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures from the National Museum, Kabul . Pp. 280-283; Sarianidi: Bactrian Gold. Pp. 252-253; Sarianidi: Khram i nekropolʹ Tilli︠a︡tepe. Pp. 110-114.

- ↑ V. Schiltz: Tillya Tepe, Tomb VI . In: Afghanistan: Hidden Treasures from the National Museum, Kabul . 2008, pp. 284-293; Sarianidi: Bactrian Gold. Pp. 254-259; Sarianidi: Khram i nekropolʹ Tilli︠a︡tepe. Pp. 114-131.

- ^ John Boardman: The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity. London 1994, ISBN 0-500-23696-8 , pp. 118-119; see. the golden figures in Hellenistic style from Taxila, which are very similar to those from Tilla Tepe: John Marshall : Taxila III. Cambridge 1951, plate 191, pp. 96-98.

- ↑ K. Enoki, GA Koshelenko, Z. Haidary (ed.): The dark ages , In: János Harmatta: History of civilizations of Central Asia, Vol. 2; The development of sedentary and nomadic civilizations: 700 BC to AD 250. Delhi 1999, ISBN 81-208-1408-8 , pp. 185-189.

- ↑ Sarianidi: On the culture of the early Kusana . In: Jokob Ozols, Volker Thewalt (ed.): From the East of the Alexander Empire, peoples and cultures between Orient and Occident, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India . P. 98.

- ^ John Boardman: The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity . London 1994, ISBN 0-500-23696-8 , p. 128; see. M. Taddei: New Research Evidence on Gandhara Iconography . In: Jokob Ozols, Volker Thewalt (ed.): From the East of the Alexander Empire, peoples and cultures between Orient and Occident, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India . Cologne 1984, ISBN 3-7701-1571-6 , pp. 154-175.

- ^ Benjamin Rowland: Zentralasien, Kunst der Welt , Baden-Baden 1970, pp. 23–24, ISBN 3-87355-193-4 .

Coordinates: 36 ° 41 ′ 40 ″ N , 65 ° 47 ′ 21 ″ E