Roman constitutional law

The Roman constitutional law treats the constitutional bases for action at the highest political offices of the Roman Empire from the 8th century BC. BC and the 7th century AD are primarily affected by the senior officials of the respective epochs, first the kings, then the praetors and consuls, and later the emperors. In addition, the right of the magistrates standing under the consuls , which lie within the official career path, the cursus honorum , is important. Outside of the official career, the Roman Senate and the office of dictator are recorded as constitutional sovereigns . The Senate played a permanently active role in Roman constitutional life, although its initially very high authority was increasingly undermined over time. Other offices arose and went out. The popular assemblies and tribunes were also outside the official career . There was never a written constitution.

Roman constitutional historiography is considered to be very uncertain about the ages of the royal era and, to a large extent, the republic as well. The sources of the records preserved and the way in which they have been used often raise questions of credibility. In the best case scenario, there are ancient reports that have been handed down orally and are basically authentic despite possibly many decorations. In the worst case, fictions are superficially based on actual events, but do not provide any certainty or guarantee. Historians who see the republic as a further development of the monarchy and the consuls as the successor to the kings have either reconstructed the constitutional relationships or taken them from an old tradition that prevails in the popular consciousness, which may have been changed and embellished during the republic, so that it is entirely may be false narratives, which however correctly reflect the old law. The early imperial period is neat, the late imperial period well attested.

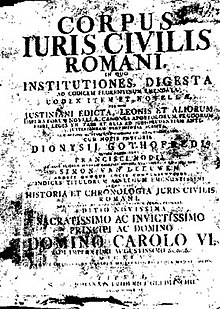

In contrast to Roman civil law, which has an extensive history of reception , Roman constitutional law was only adopted and further developed in the following period when it was compatible with the medieval (in Germany late medieval ) constitutional conditions and did justice to the constitution of offices. The majority of the public law texts of the "work of the corpus iuris ", which was primarily received from the time of the Glossators , were either eliminated due to inconsistencies or the content was completely reinterpreted. The remaining texts were used by the Hohenstaufen universal empire , then the Western European monarchy and finally the German territorial principality to formulate their own imperial claims to sovereignty. In this context, they also called for a monopoly on legislation and jurisdiction. This paved the way for modern official and legal concepts.

Constitutional classifications

According to the prevailing view of legal historians , the Roman sphere of influence is constitutionally divided into four periods. Usually the presentation is based on the sequence of different forms of government as classification criteria. These should be followed. Thereafter represented from 753 to 510/509 BC First, the predominantly legendary Roman royal period, the rulership in Rome. It was followed by the year 509 BC. Chr. Mentioned as the beginning, with the replacement of the monarchical structure the Roman Republic . It was aristocratic and increasingly included democratic features. 27 BC In BC Augustus brought the republic into the age of the principate , which is used synonymously for early and high imperial times. The principate put an end to the decades-long domestic political struggles from which the forces of the aristocratic republic had emerged as losers. Sulla's efforts , later Caesar's , to create orderly conditions within the framework of a comprehensive dictatorship only catalyzed the state emergency because the republic could not be "restored" as desired. The beginning of a system change towards the establishment of the empire is therefore fundamentally undisputed in research. It is then more difficult to determine the end point of the imperial era. A multitude of events theoretically allows for an equally multitude of constitutionally conceivable turning points.

Mostly, the research agreed today that with Diocletian from 284 n. Chr. The period of late antiquity (in the older old historical research as Dominat called) began. The principate and the late imperial era were both monarchical, but the separation is constitutionally based on the different structure of the imperial power. The empire of the early period was - with all power over the subjects - strongly bound to the law, whereas the late antique emperor saw himself as law and was freed from all legal obligations. This found expression in a considerably increasing need for the drafting of imperial constitutions. The determination of the end of late antiquity presents research again with (even greater) difficulties. Mostly the end of late antiquity coincides with the end of the reign of Justinian I. Justinian was the last emperor who made a serious attempt to restore the unity of the empire by, among other things, “collecting” and re- codifying classical law .

The epochal constitutional division is opposed by the following criticisms, which call for a different division.

From a political point of view, it is argued that the royal era and the republic basically shaped a common and continuous development process. A differentiation could be made more sensibly according to formative legal and social events that would have brought about actual changes. From 367 B.C. It becomes clear that an originally patrician aristocratic state has transformed into a patrician- plebeian nobility . The decisive factor for this was the long clashes between patricians and plebeians, which ultimately brought lasting advantages to the latter. This process of change began with the codifications of the Twelve Tables Act / around 450 BC. And the lex Canuleia / 445 BC BC, which was preceded by a secessio plebis . As a result, the plebeians received their first recognition in the civil law area in order to achieve the great breakthrough in 367 BC. With the decisive of all secessiones plebis, with which it was achieved that the leges Liciniae Sextiae could be launched, a package of laws that assured the plebeians that they had access to the most important magistrates, the consulate and the praetur would get and thus direct participation in state affairs. This legal concession, in turn, not only ended the conflict of estates, but also decisively advanced the development of the ensuing constitution.

From the point of view of social and economic history , a distinction is often made between a peasant state and an imperial phase. Until the middle of the 3rd century BC Chr. Rome was a rural communal state only. This state has drawn its regulations from long-tried (longa et invertata consuetudo) and undisputed (consensus omnium) common law , as well as the fathers' holy custom, mos maiorum . He regenerated himself by discarding outdated or not applied legal concepts . This archaic peasant state was joined by imperialism , which was characterized by hegemonic world domination that lasted until around the end of the 3rd century AD.

Differentiation from private law

Compared to the much-noticed Roman private law , which was occasionally codified, constitutional law was largely unwritten law. Legal sources were primarily customary and sacred law practices based on the tried and tested principles of the mos maiorum , traditional, generally recognized and frequently applied. There was also no principle of the separation of powers in ancient Rome , so that constitutive elements of the constitution , administration and jurisdiction appear to be largely “interwoven” in all forms of government.

Like constitutional law, Roman private law is divided in time. An ancient Roman law with a peasant state constitution (Twelve Tables Age and older republic) was followed by a (pre-) classical age following the Punic wars , which produced high-ranking jurisprudence in the younger republic and under the principality . This was followed by late antiquity , in which opposing tendencies established themselves in the greatly simplified, post- Diocletian Vulgar law . Insofar as Vulgar law, which was primarily based on customary law, remained formative in the west of the empire into the Middle Ages, it was overcome in the east by a kind of classical renaissance and culminated in the compiled codification of Justinian .

The constitution of the royal era

Sources

The ancient texts, which provide information about the first centuries of Rome, have long been considered reliable historiography. Gradually, however, it became clear that they suffered from countless inconsistencies. In addition, the assumption arose that the writers of antiquity must have been at least partially aware of this themselves. Today researchers agree that knowledge of the constitution of the Roman kingdom must be viewed as poor. To make matters worse, in the early Roman times only a few written works were created and these were largely created during the conquest of Rome by the Gauls in 390 BC. Were lost. Thus, by the end of the Roman Republic, the available material was scarce.

The working methods of the early historians in no way corresponded to today's demands. References to historical sources were not made at all, or only in passing. Often the descriptions from the sources for further processing were not even mentioned or were randomly spun off. For example, Dionysius of Halicarnassus claims to have studied the literature of Quintus Fabius Pictor . However, the lack of source references make it almost impossible for the attentive reader to gain control over the text, because the author had already given them away due to his way of working. Other authors, such as Titus Livius , for example , renounced a variety of sources and followed - often uncritically - only the preferred source, the validity of which is currently unknown. The critical questions about the sources can only be overcome to the extent that a large number of reports on the same circumstances are suitable for (at least limited) mutual control. A deviation from the tradition, however, remains undetected if the historians repeat themselves consistently.

Nevertheless, we have the most detailed reports on the Roman royal period Titus Livius in his "Roman History" and the Greek Dionysius of Halicarnassus in his "Roman Archeology", both sources from the second half of the 1st century BC. It can be assumed that the historical facts were mixed with legends long after the events. The sources, on the other hand, consistently report that Rome was originally ruled by seven kings. In addition, the explanations convey facts that allow a list of kings to be drawn up. Even earlier reporters were Quintus Fabius Pictor and Lucius Cincius Alimentus , who are among the oldest historians. Both were senators who wrote in Greek and were listed by Livy as very precise informants. Of secondary importance is literature about the royal period, which Marcus Porcius Cato ( Orgines ) and Lucius Calpurnius Piso as well as Naevius and Ennius left us . Among the "late republicans", for example, Valerius Antias , Licinius Macer and Claudius Quadrigarius dealt with kingship. Remarks by Cassius Dio are largely insignificant, since the books relating to the royal period - apart from a few fragments - have been lost.

Lore about the exaltation of the king

The establishment of Rome as a fortified city left the cultural sphere of influence of the Etruscans in the early 6th century BC. Attributed to BC. According to the legend of Romulus and Remus , the event is dated April 21, 753, in an environment that Martin Schermaier presented in a peaceful manner: “The history of Roman universal law begins in a community whose conditions we can hardly imagine modest enough . “But: 300 BC An unknown Greek author had put together various traditions. According to this, at least the first three kings must have been interpreted as such, Romulus as the city's founder, Numa Pompilius as the priest-king, and Tullus Hostilius as the warrior-king. Functionally, the kings held the highest command of the army and the highest priesthood . Theodor Mommsen also addresses the most original royal function of all, that of the supreme judge within the framework of state jurisdiction.

It is unclear according to which rules the king (rex) gained power. Basically, it is assumed that it was not based on succession, because this reference is made in written documents about the only exception recorded by Livius: Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, who was reaching for power, is said to have been responsible for the death of his predecessor Servius Tullius , for whose “iusta ac legitima regna “To extinguish. The sources are silent on a previous designation. It is possible, however, that the royal dignity was hereditary, because there are indications for this too. For example, King Ancus Marcius is referred to as the grandson of King Numa. According to Livy, his sons are said to have commissioned the murder of the Etruscan L. Tarquinius Priscus in order to know that the "usurper" had been eliminated, because they saw themselves as the legitimate successors of their father. In fact, Servius Tullu's son-in-law becomes his successor. Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, on the other hand, is said to have not only been the son-in-law of Servius Tullus, but also the son or grandson of L. Tarquinius Priscus. Like his two predecessors, L. Tarquinius Superbus was of Etruscan origin , two of them even of Tarquin origin.

Archaic law must be described as genuinely Roman. Connections to Etruscan or Greek law are not proven. It was shaped solely by religiously motivated ritualism. The details are unclear and hypothetical, but for the legal historian Wolfgang Kunkel , the ascension of the king is most likely a mystical act. In the augurium, the priests of the oldest college of priests, the augurs , interpreted the signs of the gods according to special rules. Dionysius of Halicarnassus and Livy unanimously report that Romulus, like Remus, received an augurium, one with twelve vultures, the other with six vultures. Livy also describes the augurium in Numa Pompilius in detail, but then the auspices break off for the time being, because Tullus Hostilius and Ancius Marcius are said not to have received any. They were "determined" or "elected" by the people ( iussit , creavit ) and they were confirmed by the Senate. In the literature of Dionysius of Halicarnassus, it is striking that he always refers to the “signs of the gods”. Only Lucius Tarquinius Priscus and Servius Tullius received an augurium as the insignia of their chosen status. The last king, Tarquinius Superbus, was no longer supported by the will of the gods, to which his overthrow is ultimately attributed. Legend has it that the fall of the Tarquinians did not completely end the monarchy for Rome, because the Etruscan king of Clusium , Lars Porsenna , conquered Rome at short notice, was 503 BC. BC, however, again in the past.

Lore about the exercise of royal power

If the Roman king was in office, he had the religious and magical functions described above in personal union. His office brought with it extensive customary and sacred powers. The king confirmed thaumaturgic powers before the popular assembly ( inauguratio ) , comparable to the Germanic sacral kingship . He was able to obtain the signs of the gods in order to reach a judgment , mostly with the help of the priests' college. The most difficult cases were decided by divine judgment . Since the curial assemblies watched over the cult , they were tasked with smoothing the divine path for their royal leader when he was inaugurated by the augur and with confirming his acquired competence on the basis of the lex curiata de imperio .

The king's political power thus had a sacred origin. While three of the first four kings of the early period performed their functions more or less in the sense of a present-day state presidency , the three rulers who followed Lucius Tarquinius Priscus performed their tasks in a much more absolutist way. It was also Tarquinius Priscus who laid the foundation stone for the centurion , the hundreds of citizens who militarily formed the Roman legion . The central assemblies negotiated on the Field of Mars and thus outside the city limits . These assemblies exercised supreme political power. They elected senior officials who voted on war and peace, had legislative powers, and led criminal capital trials. The Regia , which was traditionally referred to as the seat of government of the second Roman king Numa Pompilius and is considered one of the oldest buildings in Rome in written tradition , was built in the eastern part of the Roman Forum in the early phase of the royal era .

In ancient legal life, the social, moral and questions of origin based on rules were of great importance. They were based extensively on "lived practice" and hardly on "established law". The latter was represented by “royal laws”, the leges regiae . King's law is also said to have been a killing law ( paricidas law) of King Numa Pompilius, today understood as the first trace of an archaic criminal law . This assessment is based on the fact that archaic societies did not in principle have any state criminal law. The members of the kin were responsible for retaliation for criminal offenses . Blood revenge is said to have been banned under Numa Pompilius . According to modern understanding, such a prohibition means a right of defense against everyone . Regarded as unusual from the legal tradition, the ban severely restricted the traditional clan order. Numa was often received as a civilizational innovator, for example with Cicero in De re publica , with Ovid in the 15th Book of Metamorphoses (verses 1–11) , with Virgil in the Aeneid , with Plutarch and Titus Livius. In unison, the authors attested that King Numa had a foresighted and deliberate government action, which gained a high reputation and was therefore called on for arbitration functions.

Social order

The predominantly Roman-Latin inhabitants of Rome were predominantly dominated by the Etruscan noble families. The heads of these aristocratic gentes were allowed to appoint senators, but their political rights did not go beyond advisory activities during the royal period. It is still a matter of dispute whether there was a Senate at all during the royal period. To the extent that it was answered in the affirmative, it is stated that during the imperial era, self-evident core competencies, such as those relating to legislation and the exercise of veto rights, are said to have been denied the Senate during this period. At best, he was given responsibility as a "Privy Councilor", an advisory body to the monarch. In addition to advisory functions in this respect, the senatorship may have provided interrex , a supreme administrator for official business that arose between the reigns of the kings. The “gentes” also made up the people's assembly, which was subdivided into 30 sacred associations, the so-called curiae . These were each recruited from families of common descent. Ten curiae each formed one of the three tribūs , Ramnes , Tities and Luceres . The names of the tribūs are of Etruscan origin, which is why it is assumed that their order scheme is one of the first acts of a state organization in Rome. In the course of the meetings of the Curia, the people's assembly mainly performed religious and ritual tasks.

The family (familia) was part of the social order of the royal era and the basis of the constitution . The family household consisted of people, animals and things and was entirely in the hands (manus) of the pater familias , who exercised all power on his own responsibility ( patria potestas ) . The wife joining the family and the wives of the sons and grandchildren were also subject to paternal domestic authority.

In public magistrate law, where civil servants were inaugurated, but also in the civil law segment of legal transactions, traits of the ancient Roman religion became visible, for example in the form of the important types of business of manzipation and stipulation . Not only were they ubiquitous, their influence extended well beyond the era of the XII tablets.

The Constitution of the Roman Republic

According to tradition, the time of kings began with the overthrow of the last Etruscan king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus in 510 BC. Ended. The starting point for this is said to have been the “ desecration of Lucretia ”, dismissed as a later invention by ancient historians , celebrated as the founding myth of the republic. The legend, however, emphasizes the authorship through an anti-monarchy aristocratic revolt. After initial turmoil, the nobility established the senate as the dominant arbors because it was composed of representatives of their interests (nobility council). From then on, the Senate determined the praetor maximus every year . This annual magistrate was responsible for the overall function of government affairs.

With the king only the religious functions remained. He officiated as rex sacrorum , which was sometimes referred to as rex sacrificolus , rex sacrificiorum or rex sacerdos . He performed ritual services to Janus . With the advent of the Jupiter priest, its meaning probably waned again, whereby the main focus of the worship cults is disputed in detail. On the other hand, it is undisputed that as a remnant of the royal times, the rex sacrorum - despite the highest rank of priest - was hierarchically subordinate to the pontifex maximus . This was not without reason, because the political elite of the republic and even the imperial era were worried that the royal office might regain strength. In order to prevent the regeneration of royal power, the office was supervised.

The political office of interrex is also a reminder of the royal era . Livy dates the emergence of the service in the sense of this title to the time that immediately followed the first king Romulus: It was unclear who should follow Romulus, which is why ten decuria were formed, which elected a chief who changed every 5 days and with empire and was equipped with a licit escort ("cum insignibus imperii et lictoribus"). At that time it was considered interrex. However, popular discontent led to the election of the second king, Numa Pompilius . The office of interrex later acquired importance for the interregnum between the kings and continued to exist in this form in the republic in the event that both consuls had left their offices prematurely. The last time it happened was 52 BC. Chr.

Many researchers believe that the actual consular constitution was only established later. During the time of the republic it remained formally in force, even until the reorganization by Emperor Diocletian (end of the principate). Royal insignia such as the ivory scepter and the ivory throne, following Dionysius, are said to have played a role even with the first consuls.

General legal developments

On the surface, the constitutions of the royal times and the republic are similar. The offices and functions are basically still called the same. However, a closer look reveals a shift in the importance of the institutions. It is true that political power still rests with the magistrate, partly with expanded functional and partly with reduced competencies. The Senate, which had been given extensive rights in its new composition, had become a serious opponent. He was able to influence government affairs independently. The Volksgemeinde also took up part of the magistrate's loss of competence and was responsible for its own political legal competence.

With the fall of the last king in 510 BC In addition, the College of Pontifices came into the public eye. They were state priests who were primarily committed to cult and rite. They contacted the gods by means of sacrifices, they formulated contracts and set up the rules for the citizens to honor the gods and prosperous life among one another. They all held authority under sacred law (ius) . They arranged for the court days and programs to be set , and provided the formulas for each type of claim. During the “middle republic” the pontifices gradually assumed the leading position in the clergy. The rituals and language that accompanied the drafting of the law and the regulation of the conditions of legal transactions differed considerably from that of the augurs, so that soon there was talk of the “pontifical jurisprudence of the republic”. The laws were interpreted strictly literally. Scope for legal interpretations or even analogies were completely excluded. Because of their indomitable and rigid adherence to these principles, the clergy came to life by the middle of the 2nd century BC. In the reputation of an inflexible "pontifical rigorism".

For foreign affairs, the pater patratus from the priestly college of the fetials became important. He was responsible - the historicity is controversial - the task of concluding conjured agreements ( foedera ) , which served the friendship, alliance or peace settlement.

Increasingly, the increasing Greek influences opposed the rigorous legal system. 156/5 BC An Athenian embassy held lectures in front of the Roman nobility. The metaphysical universal doctrine of the Stoa entered Roman society with it and also rubbed off on late Republican jurisprudence. Some excellent lawyers such as Publius Mucius Scaevola and Publius Rutilius Rufus , who began to combine conventional jurisprudence with what is now scientific standards, should be mentioned as examples. With the newly founded schools of law , an initial legal methodology developed which also redefined traditional technical terms.

Helmut Coing attributes many of the ideas indirectly to Aristotle , because the sharpening and contouring of individual legal institutions as well as their illustration based on the principle of the formation of conceptual contexts refer to this most important pioneer of scientific and state theory . The logic of legal work concentrated on the abstraction of legal sentences and looked for initial and final justifications for chains of thought. This improved the power of argumentation and the legal design economy suddenly. The methodical interpretation of legal norms gained additional effectiveness through the introduction of the dialectical reversal of theorems, for example through the argumentum e contrario and the argumentum a minori ad maius . In sum, they belong to the general argumentation that Aristotle had discussed in his Topik with the aim of drawing conclusions from probable sentences of any content.

In his Topica Cicero presented a whole series of such final forms to a friend (Trebatius) in application to legal problems. He expressly thought of his role model Aristotle.

In particular, the ancient understanding of justice was introduced in law. Previously, the user of the law had limited himself to strict compliance with the law. It was inevitable that a principle of good faith (bona fides) emerged, which was carried over into modern law.

Constitutional elements and legislative powers

A written constitution in the formal sense did not yet exist. It took centuries for the rules of the republic to crystallize. With reference to this, some principles acquired particular significance. So initially the annuity principle applied , all magistrates could only be exercised for a period of one year. The iteration ban was linked to the annuity principle . A second term of office had thus been ruled out in order to revive government business and political renewal. Officials were also forbidden from holding offices in a contiguous manner. With the exception of the office of censor and the dictatorship, all other offices were occupied by at least two people at the same time, that is, collegially . Intercession rights were used for mutual control and every incumbent could prevent, even reverse, decisions made by his colleague. Anyone who had previously assumed the next lower office within the framework of the cursus honorum was legitimized for an office .

The theoretical definition of the republican consular constitution is problematic. Since the principle of the division of powers did not prevail in antiquity, today's observer is amazed at the peculiar confusion of fundamentally different tasks within one and the same magistrate . Civil and public tasks clashed in one function, as did legislative and administrative activities. A constitutionally pure form of rule cannot be determined either. The research therefore most likely assumes a mixed constitution , which is composed of monarchical , aristocratic and democratic elements. Even Polybius characterized republican Rome in his historiography as a complex combination of individual constitutional elements. The principle of monarchy is shown in the consulate, that of the aristocracy in the senate and that of democracy in the popular assembly. It is assumed that the highest possible stability should be achieved with this construct.

Legislative powers and formal competence for legislative procedures lay in different hands in the Roman Republic. The most important form of law was the leges , and the comitia were responsible for enacting them . These were structured in a complicated manner and organized according to fixed procedural rules. At the end of the republic the prominent plebiscites ( plebiscita ) arose , they were decided by the assemblies of the plebs . Leges was the model for the legislative process. The Senate resolutions were not part of the law ; they only entered legal development history in the imperial era. According to the Republican understanding, they were non-binding recommendations, communiqués . Finally, each magistrate was authorized to announce the measures in his area of competence that would become binding during his term of office. Despite their immediate effect in everyday legal practice, these so-called edicts were not laws. They lacked the character of continuity. With the resignation of the magistrate they expired again.

Legislation should help to deal with problems in a targeted manner and to control social life. This was already intended in the XII Plates, because they did not represent a learned epistemological legal record, they expressed political goals. The recording itself is used to maintain legal peace. Political influence in the legislative acts became even clearer in the "Gracchian reform legislation" or in the "Augustan marriage laws" of the early imperial era. And it was still the intention to overcome an emergency when Diocletian initiated the economically motivated price regulations at the beginning of late antiquity. The measures resulted in the individual law . Often the laws were defensive attempts by creating circumvention facts.

Monarchical elements

Basics

In the beginning the praetor maximus is said to have stood. As the only senior official, possibly the bearer of old royal authority, he could have emerged from the royal era. Possibly based on him, the consulate was established through the Leges Liciniae Sextiae . It is debatable whether the consulate had already existed when the last king was overthrown. The legend emphasizes that the first consul was Lucius Junius Brutus . During the republic the office became the highest state power. This went from the 4th century BC. From two consuls. In a functionally modified form, the praetor maximus seems to have initially preceded the consuls within a college of three. The sources throw no clear light on the history of the development of the relationship between the consuls and the praetor. No later than 367 BC. In any case, the consuls were given the task of working together as colleagues. They held imperium maius , which meant unlimited authority. The entire civil and military administration, judicial and legal sovereignty, the right to appoint senators and the authority to convene the Senate and the People's Assembly were subject to their supervision.

Reservations, Limitations, and Rights of Intervention

In order to effectively counter potential abuse of law and power by the consuls, foreign and financial policy was assigned to the Senate. The tribunes were given veto rights and were considered sacrosanct , i.e. inviolable. The praetur was given the jurisdiction of the ordinary jurisdiction (iurisdictio) . At the beginning of a year in office, the praetor laid down the principles of the application of law and the promise of legal protection (lawsuits, objections and objections). From 366 B.C. The fiscal affairs and the organization of the army were passed on to the censor , who from 312 BC. In addition, instead of the consuls, the right to appoint senators was given.

As the collega minor of the consuls, the praetor had imperial powers. He could consuls in times of war or due to any other absence represented . Around 242 BC In the 3rd century BC the city praetor ( praetor urbanus ) was assigned a foreign praetor ( praetor peregrinus ). This led the processes of non-citizens . From 227 B.C. Further praetors were appointed to administer newly acquired provinces . The city praetor was able to use his authority to issue orders to further develop legal regulations. The prominent XII panels were increasingly subject to current interpretability. This increasingly triggered "magistrate creation of law". Iulianus , a recognized lawyer during the reign of Emperor Hadrian , formulated a final version of the praetoric edict, the edictum perpetuum , in 130 AD . This was no longer a praetoric certificate of omnipotence in legal matters, because the development of the law was already in the hands of the emperor and his legal advisers at that time.

Another organ of order were the lictors . Outside the city limits, they were equipped with the official symbol of the highest rulers, the lictors' bundle . Within the city limits, Roman citizens had the right to provoke the people's assembly if they felt they were affected by the violence of state magistrates. Aediles , tribunes and quaestors had no empire. They exercised objectively defined and subordinate official powers, aediles in the context of care as grain supervisors, organizers of public games and the police, quaestors as supervisors of the state treasury.

The consuls had veto rights (iura intercedendi) which they could assert against praetoric orders. In times of crisis, the college of consuls was allowed to dissolve in order to be able to transfer the official duties to the dictator. That in turn was not subject to any restrictive measures, because he was a super powerful extraordinary civil servant, solely committed to the task.

The royal office degenerated into the rex sacrorum ; his dignity was exhausted in the powers of the religious sacrificial king. This office was allowed to exist because certain sacred tasks were still to be performed by a "king" (a person with this title).

Aristocratic elements

The control and legislative body of the Roman Senate represented a classically aristocratic body . Kunkel spoke of him appreciatively as the “dormant pole of Roman state life.” In the time of the king, he only belonged to members of patrician noble families who were “born” into the relatively insignificant office. During the republic the senate became very important, the senators were first from the consuls, from 312 BC onwards. Appointed "for life" by the censors . To emphasize the importance, initially only former magistrates with imperium were considered, i.e. former praetors and consuls. Later, subordinate officials could also be promoted to the senatorial nobility if they had completed the cursus honorum. From the end of the 3rd century BC The office was even open to curular aediles, from the end of the 2nd century BC. People's tribunes and plebeian aediles, from 81 BC BC Quaestors. The Senate List (lectio senatus) was drawn up regularly every five years in the “high republic”, which is why it could take a long time for a senator to officially join it (qui in senatu sunt) . Under the dictator Sulla, the number of senate members was doubled from 300 to 600 people due to the weakening of personnel as a result of the civil war. Under Caesar the number rose temporarily to around 900 to 1000 senators. Senate resolutions required a total of 100 votes. The most important meeting place was the Curia Hostilia on the eastern edge of the (today's) Roman Forum , after which it was destroyed in 52 BC. BC, Iulia Curia . Occasionally the Senate avoided its meetings in temple complexes, such as the temple of the Capitoline Iuppiter or the Dioskurentempel .

The Senate was convened by an imperial carrier as soon as the advice was needed. The Senate could only give advice de jure , but de facto it made politically important decisions. Not legally restricted by annuity or collegiality obligations, he was able to work with a high degree of continuity and at the latest in the times of the "late republic" acted as the actual governing body of the res publica.

Whether the Senate should be understood as a legislative and executive body in the constitution of the republic was a particularly controversial issue in the 19th and 20th centuries. While the ancient historians Theodor Mommsen and Joseph Rubino understood the Senate merely as a “strengthening of the magistrate”, which makes it appear as an accessory component of overall political decision-making and moreover comes close to a “basic monarchical idea”, this view is now considered outdated. If one follows the legal historian Wolfgang Kunkel , the Senate created constitutional law. Representing large parts of constitutional research, he even assumes that the Senate - at least in the late Republic - was the dominant constitutional government body. In addition, Kunkel refers to a Ciceronian speaking office which emphasizes that all office holders (magistrates) were subordinate to the will of the Senate. This in turn continued a tradition that Romulus had already felt in the tradition . The state-theoretical work of Cicero, De re publica , contains the evidence that Romulus' powers (auspicia) were limited by an equal senate, which was placed at his side (... et senatus) . He does not see the Senate in such a way that it was primarily the legislative body (legislature) and, in addition, in the area of the executive it was a mere supervisory body, but rather that it represents the executive in cooperation with the magistrate itself. that it draws a parallel to the administrative work and sovereignty of the German municipal council (at the municipal level). According to Romanist Max Kaser , there were two independent legitimators in Rome's popular order: on the one hand, a legal order, and on the other, a law-free order of power. In his opinion, the Senate “existed alongside the law”.

Senate resolutions were subject to the auctoritas senatus . Although not constitutionally binding, they were regularly implemented by the magistrates. The high level of identification with the Senate is expressed in the national emblem S.PQR , senatus populusque romanus ("Senate and People of Rome"). By means of the senatus consultum ultimum , the Senate was able to declare a state of emergency and delegate dictatorial powers to the consuls. Part of the history of the Senate of this time is that Julius Caesar rose against him, disempowered him and, accompanied by the ongoing civil war, had himself appointed “dictator for life”.

Democratic constitutional elements

Basics

| Constitutional body: |

state-theoretical classification: |

| Consulate | monarchical element |

| senate | aristocratic element |

| Roman people | democratic element |

The popular assemblies, on the other hand, were democratically structured and organized in tripartite terms. As part of the comitia , the people as a whole (populus Romanus) expressed their political will. The meetings of the Curia , which still existed towards the end of the republic, but were no longer a real assembly of the people , were brought over from the royal era . Their function was exhausted in the formal confirmation of office of imperial holders and the participation in two classic private legal acts , the adrogatio (adoption in lieu of sons, adoptive law) and the testamentum calatis comitis (questions of inheritance). The central assemblies , originally army assemblies, elected the censors, consuls, praetors and the highest guardian of the ancient Roman gods, the pontifex maximus . The latter was in charge of all sacred affairs. In the legislative people's assembly, however, politically important decisions about war and peace were made, laws passed and crimes were negotiated. In a third popular assembly, the urban tribal assembly , which was divided into 35 tribūs during the middle republic , aediles, quaestors and the vigintisexviri were elected. The latter were simple judges or civil servants (magistrati minores) , who usually held court hearings before they entered the senatorial office. The first 21 tribūs of the Roman national territory allegedly emerged as early as 495 BC. After the creation of another 14 tribūs in the 4th and 3rd centuries BC. Were in 241 BC. Decorated in BC Velina and Quirina . With the odd number of tribūs, the comitia tributa wanted to prevent stalemates from arising during votes.

In the legal arbors of the “ concilium plebis ”, the people conducted their special negotiations to the exclusion of further public. The body was organized in a similar way to tribal assemblies and met in the comitium . There the tribunes and the plebeian aediles were elected. The concilium plebis was not bound by the recommendations and guidelines of the Senate.

Historical development of the plebiscite

The election of the highest civil servants, including the consuls, was thus placed in the hands of the “comitia centuriata”. Since the Leges Liciniae Sextae , this office has also been open to plebeians, first practiced in 342 BC. The people's tribunate, which emerged from the internal ruling class of the “plebs”, elected in its meetings (concilia plebis) initially two and later ten permanent representatives of the political interests of the aristocratic-patrician government, the tribuni plebis . They were provided with property rights of their class (ius auxilii) and rights of intervention (ius intercedendi) . How new law could be established and the state changed is illustrated by the emergence of the tribunician power of the people's assembly that emerged from the disputes . The "plebs" demanded access to the higher administrative offices, because so far a career beyond the office of aedile was denied him. The plebeians moved out of the city to the Aventine to put pressure on their demand for equality. A city extract (secessio plebis) was understood in Rome as a "strike measure" and condemned as an illegal act of violence. Nevertheless, the patrician opposing side tacitly tolerated him, as there was a fear that the plebeians would intensify their rebellions. In fact, this meant the introduction of the people's tribunate , because the patriciate began to accept toleration as a factual legal status. The “plebs” directed their inviolable right of intercession against any office, the patricians were limited to the popular assembly. An illegally established panel had legalized itself. Ultimately, the tribunes were integrated into the cursus honorum. The lex Ogulnia 300 BC. BC allowed plebeians to exercise pontificate and augurate. Even in the late phase of the republic, under Sulla, the tribunate was again extracted from the cursus .

Laws also strengthened the "plebs". The lex Hortensia (287 BC) made decisions legally binding. Plebiscites were binding on the entire state beyond the borders of Rome. From then on, plebiscita were called leges . The lex Aquilia (286 BC?) Regulated claims for damages and came about through the first plebiscite , one of the last plebiscites was the lex Falcidia . The lex Claudia de nave senatorum was even enforced against the resistance of the Senate.

Development, crisis and fall of the republic

After the end of the class conflicts and the domestic peace treaty in 367 BC BC (leges Liciniae Sextiae), the now consolidated Rome aimed for dominance in Latium . She achieved this in 338 BC. Until 275 BC. All of Italy was subjugated. Rome rose to become a great power, which sparked covetousness with Carthage , which ruled the western Mediterranean. With the First Punic War , Rome annexed itself in 241 BC. His first overseas province with Sicilia . The empire continued to expand during the Second Punic War in 201 BC. BC Hispania . By means of cleverly forged alliances, otherwise true to the motto “divide et impera” (“divide and rule”), Rome brought up to 168 BC. BC large parts of the Hellenistic-oriented east of the Mediterranean under control. Some of the areas conquered in this way were granted graduated rights of self-government, and others were transformed into Roman provinces . This is how Africa , Achaea and Asia came into being . Roman governors were installed in the provinces and Roman people were settled in the hope of consolidating their direct influence in the region.

However, it turned out that those constitutional mechanisms that had functioned perfectly during the internal Roman class conflicts were unsuitable for an unassailable world empire. Envy, resentment, corruption, blackmail and excessive thirst for power characterized the conservative-patrician and senate-loyal Roman nobility as well as the patrician-plebeian money aristocracy. Then the Gracchian Reform ( leges Semproniae and lex Sempronia agraria ), a land and social reform package to restore the once free peasant state, failed . Especially the Marxist research emphasizes that elements of decay lay in the faulty management of the means of production , in particular the increasing loss of common property and the brutal ancient slavery should be mentioned in this sense . Late republican imperial Rome experienced a profound change in economic relations in the Mediterranean, where it exercised its predominance. Imperialism and a society based on slavery led Rome into a mode of crisis that escalated in the middle of the 2nd century, drove the republic to the abyss and brought about the transition to the imperial era.

Sulla was one of the most influential witnesses of the Gracchian reform efforts . He saw the beginning of a story of constitutional violations and acts of violence. So he noticed that the Senate was simply bypassed in bills and also registered that the people's tribunes were curtailed of their rights, because they could no longer put forward intercessions against bills. Property rights were unlawfully interfered with, as well as senatorial sovereignty, such as financial administration (heir of King Attalus of Pergamon ). This prompted the Senate to declare a state of emergency. When the dead were to be lamented, a real crisis arose. At the center of the struggle for power were the camps of the optimates , who defended the conservative ideals and domination of the nobility and the senate, and the populars , representatives of the people . In times of war it became apparent that the commandant's word of power made the soldier more capable than identification with the republican state. An open civil war soon raged . Constitutional dimensions also adopted the Social War in a battle of Italic tribes to Roman citizenship. Ultimately, Sulla claimed dictatorial means to regain republican supremacy. The necessary legitimation was provided to him in 82 BC. The Lex Valeria . After Sulla up to 79 BC. Chr. Had initiated a large number of laws for the reorganization and restoration of the republic, he resigned his offices and resigned.

Soon, however, the call for a "strong man" was again loud. Julius Caesar heard this. Caesar also became a dictator with many extraordinary powers. He planned far-reaching legal measures. He also wanted to rewrite parts of the constitution, included in the leges Iuliae . He intended to make the special powers a constitutive element of the new constitution. Caesar anticipated elements that were to assert themselves in the ensuing principate as the emperor's claim to sovereignty, without the need for the dictatorship itself. Caesar himself was, however, 44 BC. Murdered, in turn avenged by the implementation of the Lex Pedia issued in the following year .

Mark Antony observed what was going on. The dictatorship's exceptional magistrate's office was often perceived as a driving force behind abusive interference with traditional and tried-and-tested republican values. That is why Antonius quickly brought the Lex Antonia into the Senate, because he wanted the office to be abolished. But it was less the controversial authority of the law that ultimately overturned it. After all, the Senate offered Octavian as early as 22 BC. Chr. Again dictatorial powers, which he simply refused, the decisive factor was Octavian's understanding of power, which he communicated openly. The right to place competences and supervisory oversight over those of the extra-magistrate offices (since Sulla this was the people's tribunate and next to it the Senate), he derived from the power of his imperial office, so that no further extraordinary office was required.

The constitution of the principate

With the year 27 BC In the history of the Roman Empire, the beginning of a new form of government is linked, the principate . Julius Caesar's great-nephew and adopted son Octavian had defeated his opponent Marcus Antonius, former co-member of the Triumvirate, and with him the Egyptian Queen Cleopatra . This fulfilled the main concern of the legitimation law of the Second Triumvirate , the Lex Titia . With him the turmoil of the civil war and with it the state of emergency should be overcome. The triumvirate, meanwhile capricious only in Octavian, ended by the latter by giving back sovereignty to the Senate and the people of Rome (“restitutio rei publicae”). Ultimately, this was based on far-sighted tactical calculation, because it aimed at sole rule in the empire. All he had to do was convince the Senate that his claim to sole power was closely linked to the establishment of the republican traditions, which were recognizable for everyone, in order to receive the placet for his supremacy and with it the establishment of the Julio-Claudian imperial dynasty .

Post-Republican Ideology and Constitutional Reality in the Empire

Oktavian's basic concern was to legitimize the tyranny he had established during the civil war in order to gain the acceptance among the elites that he needed to exercise his rule. For this reason he first had to formally restore the republic. On January 13, 27 BC He therefore gave all extraordinary powers back to the Senate and the people. Whether Octavian had special powers - similar to Gaius Iulius Caesar - is a matter of controversy. In any case, foreseeing that the Senate would contradict this gesture of the recusatio imperii and the related abdication, he was satisfied that he was given general imperium proconsulare , which granted him the supreme command of all armed forces. The Senate awarded him the sacred honorary title Augustus ("the sublime"; actually: "the one endowed with magical power", derived from augur ), which Octavian now bore like a name. Soon afterwards he received the tribunicia potestas (people's tribune power) for life and an equally lifelong empire "in place of a consul", which he had been doing since 19 BC. BC held. (Empire proconsulare majus) .

The republican offices were de facto devalued. Officially declared as the "restoration of the republic", in reality he had pursued its permanent transformation into a monarchy with sole rule. Characteristically, this happened in such a way that partial powers and individual rights were outsourced from the offices and extended to the emperor. So he derived from the consular authority (consularis potestas) the right to examine the suitability of candidates for office, the right of nomination (nominatio) . On top of that. He also asserted the right to recommend the candidates he had selected to the senatorial electoral body (commendatio) . Since the emperor's advice and recommendation were always accepted due to its political importance, he was able to get his way through this. Another example is the law of relations which he incorporated into himself. He was allowed to report to the Senate and, more importantly, to make motions (relationes) ; they grew into law, as it were, because a Senate resolution was no longer required. The imperial speech (oratio principis) was the legal basis . Later, a quaestoric reading out in the personal absence of the emperor was sufficient. What actually turned the spirit of the republic inside out, Augustus argued as the restoration of the republic: he, the emperor, did not assume any wrong, because he had no more legal power than the respective magistrate. What at first glance even seems plausible, because as the holder of special rights to a consular partial power, he could hardly commit an official violation of authority, is ultimately inaccurate. For what may apply to the exercise of the individual office does not apply to the exercise of the sum of all offices. The emperor could not invoke the restoration of the republic insofar as his actions were not covered by any legal basis. Rather, he ostentatiously violated the two republican bans, bans that were directed against the principle of the accumulation of offices (accumulation) and that of collegiality (no colleague). The changes in content and structure therefore only allow the conclusion that Augustus had created a different, new legal order.

The concept of the principle is derived from the Latin “ princeps ” (“the first”). Augustus led the state as the “first citizen” of civil society (princeps civium) without taking up an ordinary office. Until 23 BC After all, he was still consul. The office of the princeeps was not prescribed by the constitution, but meant sole rule. The “constitutional concept” in ancient Rome is not identical to the modern one. In this context, the research first raises the question of how he is to be defined in imperial times and how an emperor can then place himself outside the constitution.

A conceptual derivation from the context of constitutionalism of the 19th century is inadequate, as is the use of the term “constitutional law” of the present, because in both cases the demonstrable existence of a (qualified) legal system would have to be assumed, i.e. a normative construct that contains a regulates the political system at its highest decision-making level. In the absence of this correlating regulatory aspect, it must ultimately be conceded that the Roman concept of the constitution did not need this legal reference. This also means that the second formative component of the modern constitutional concept of the constitution, “legitimation”, is no longer applicable. According to today's understanding, it forms the justification for any system of rule. Since the constitution of the principate knew neither the legal definition nor the justification of the imperial apparatus, Octavian did not have to justify his tyranny legally, but only socially, when he first played back the "violence" he had taken up to the senate and the people for the purpose of retransfer.

Building on this, it is no longer astonishing that Theodor Mommsen already summarized the Augustan principate that “there has probably never been a regiment that would have so completely lost the concept of legitimacy…”.

Max Weber concludes from this that there can be at least some norms of the constitution defined in this way that enjoy no legal quality, nor any other general recognition, although guaranteed and rule-compliant political violence is exercised behind them. Such a constitutional order can incorporate different government concepts within the framework of the respective power relationships; only in undisputed areas does the character of a solid tradition work.

Finally, the historian Egon Flaig put forward the thesis that in the principality there was and could not exist any “constitutional law”. With this, he wants to give the legal guild in particular the advice that they should not try to (constitutionally) capture the political system of the early and high imperial era. The provocation in the thesis is understood by the jurists among the legal historians as a fruitful criticism of the prevailing doctrines in their circles, but it is just as decidedly contradicted. For example, it is countered that Flaig distorted the concept of constitutional law when he called for consistent competency delimitations and legitimacy for state action for his definition. Conceptually, constitutional law is sufficient for legal research as a mere legal concept of order. It is characterized by the “organization of state exercise of power in the broadest sense”, supported by a social consensus on which rules of the game should be observed. There is agreement among lawyers on this point, especially if it is taken into account that the outstandingly prominent private law of the high imperial era could hardly have developed to the extent that it was if it had encountered a legally insecure environment of state order, which ultimately inevitably lacked economic incentives would have.

Nevertheless: Augustus always presented himself as a “private man” outside of all statehood. He gave the impression that he had set himself up selflessly to protect the public order of Rome in trust. Augustus therefore derived his powers not so much from the official powers of the empire and the potestas, but more from highly personal auctoritas , as he made known in his deed, the res gestae divi Augusti .

method

Not a few political tricks accompanied Augustus on his way to sole rule. So he took over in 19 BC The office of consul, already in deviation from the constitutional doctrine of the republic, because it was there until 23 BC. Annually resumed. In order to preserve the annuity fiction, he expressly repeated the power of attorney annually, which of course was subject to pure automatism. He opposed the official proclamation of the “restoration of the republic” (“restitutio rei publicae”) with a “military empire”, which he practically perceived for an unlimited period, as he repeatedly extended it after ten years of stipulation. The same thing secured him his position of power in foreign policy. 23 BC Although he resigned the office of consul in the 3rd century BC, he had the tribunicia potestas, the authority of the tribunes, transferred for life, which allowed him all influence over the people and the Senate and his position of power in the Domestic politics strengthened.

He derived the political legitimation of the power of the tribunes from the sacrosanctitas , the ius subselli and the ius auxilii . In order to be able to claim ius auxilii for himself, he had to separate office and power. Augustus cut off the plebeian office (tribuni plebis) from the official authority (tribunicia potestas) and allowed himself only the legal authority (potestas), whereby he held official authority without having to perform the duties of the office himself. The additional release of this official authority from any time limit (tribunicia potestas annua et perpetua) meant that he held the first of the two core powers sought.

But that's not all: Augustus had a lifelong imperium proconsulare maius transferred to him by law, which pacified and administered the provinces, also in civil administration, from the Senate (since 28 BC Augustus himself was already princeps senatus there ) made possible. He now had the second core power of attorney. As pontifex maximus, Augustus was also the chief overseer of the Roman cults. In the sum of his titles he was: Imperator , Caesar , Divi filius , Augustus , pontifex maximus , consul XIII , tribunicia potestate XXXVII, imperator XXI, pater patriae and after his death deified by Augustales himself . Since the people thirsted for legal security after the turmoil of the civil wars, there was no resistance to Augustus' claims to power. He was venerated by the vast majority of Romans, and his constitutional work was even transfigured as Pax Augusta .

Magistrates, Senate and People's Assembly in principle

The magistrates continued to exist. The election of the magistrates, under Augustus still the task of the people's assemblies and since Tiberius the power of the senate, was from now on supervised by the emperor. He had both the right to propose binding candidates (commendatio) and merely to recommend them (suffragatio) . Consul became a mere honorary title for deserving officials. In order to be able to grant this recognition to as many officials as possible, pairs of consuls were appointed annually, sometimes every two months. In some cases they were given responsibility for the judiciary, which, however, largely remained with the praetor. The aediles retained their market-regulating functions, whereas the quaestors were deprived of the administration of the state treasury in order to transfer them to imperial officials. The republican treasury (aerarium) lost its importance, that of the emperor (fiscus) was actively used. The imperial success of the empire produced many civil servant positions.

The legal status of the Senate, its members were included in the prosopographia Imperii Romani , changed permanently during the Principate, because it lost all political powers to the Prinzeps. But the legislative powers also changed. The popular assemblies thus largely lost their legislative powers, because leges and plebiscita were hardly ever used with Augustus and his successors. The Lex de imperio Vespasiani is probably the last plebiscite (and thus also lex ) . In their place came the senatorial resolutions, the senatus consulta and increasingly the imperial constitutions. The Senate was monitored by an "imperial government institution" newly established by Augustus, for which the term consilium principis has become established in research . The Historia Augusta reports that since Hadrian, lawyers have been increasingly included in the imperial consilium, with Neratius Priscus , Julian and Celsus mentioned by name . This move professionalized the judicature. The aristocratic and democratic constitutional elements, which were highly praised during the republic, showed themselves to be decisively weakened during the imperial era. To save democratic legislation, a transition from an “immediate” to a “representative” procedural structure would have been necessary.

The political powers of the Senate given to the Prinzeps also represented a reversal of the path of political will-formation compared to the time of the Republic. Insofar as the Senate had previously directed its recommendations to the magistrates in important political matters, the Prinzeps now addressed his wishes Senate, which implemented the formulated projects as senatus consultum . This always supported the view that Senate resolutions have the same effect as the law. In fact, however, the Senate proceeded to form its own political will; it only supported that of the Princeeps. The decisive step was the oratio , the “throne message” of the princeps, which was read out initially in his absence and later in his presence in the Senate. Until the reign of Claudius , the Senate had mostly not referred to the Prinzeps. Now he only read out the principal manuscripts during the meeting and made them official as imperial legislation after reading them. In a certain way, the Senate's resolution lay between two imperial acts of will, the constitutional oratio (principis in senatu habita) and the final confirmatio confirming the service of the Senate .

Already in the 2nd century, the high-class legal Gaius noticed that the senatus consulta was merely a superficial upgrade. Obviously, the emperors made active use of this legal medium, because the first two centuries of imperial law were shaped by decisions by the Senate. The main focus was on status, family and public order law. For example, the Senatus consultum Velleianum forbade the courts to allow proceedings against bailing wives, the Senatus consultum Macedonianum forbade the granting of loans to house sons , and the Senatus consultum Silanianum allowed the torture of slaves in the event of the unexplained death of their landlord. The imperial handwritings ( orationes ) on which the senatus consulta was based found their way into the late antique Codices Theodosianus and Iustinianus . Otherwise, the Senate had been assigned the role of a court since the early imperial era, particularly in the field of criminal law; this in addition to the jury courts of the ordo iudiciorum publicorum and the extraordinary courts of the city prefect , the praefectus vigilum .

The comitia and the concilium plebis also lost their importance in principle. Their powers were gradually transferred to the Senate. The comitia under Augustus still regularly exercised legislative functions, for example to confirm the Augustan marriage laws . The last known law of the comitia is a lex agraria from Nerva's reign. Likewise, the election of the magistrates initially remained with the people's assemblies. This right was restricted in the year 5 AD by the lex Valeria Cornelia , when the candidates for the consulate and praetur were predetermined by a body of senators and knights. Tiberius finally entrusted the election of the magistrates to the Senate in AD 14, although the popular assemblies met until the Severan period to attend the proclamation (renuntiatio) of the election results.

The principate among Augustus' successors

The emperors who followed Augustus, beginning with Tiberius ( proconsular empire), kept this constitutional form until the end of the 3rd century AD, despite a critical legal situation. De jure, however, even after Augustus, the imperial dignity was never hereditary. The well-known heyday of the Roman Empire under the adoptive emperors ( Nerva , Trajan , Hadrian , Antoninus Pius , Mark Aurel and Lucius Verus ) was certainly based on Augustus' foundation. The same applies to the Severan era and the early soldier emperors , despite further modifications .

After Domitian's death , the respected lawyer Nerva seemed to be able to restore the republic. He enriched the principate with attractive elements of freedom (principatum ac libertatem) . Due to further research (cf. Karl Christ ) it turned out, however, that both the Senate and the people, represented by the People's Assembly, had forgotten how to determine themselves politically within a past centennium. The erasure of Domitian's memory did nothing to change that.

Trajan, whose leadership style embodied ancient cardinal virtues , was able to consolidate the principate, even though the emperors of the second four- imperial year 193 AD and the six-imperial year 238 AD suggested through murders, civil war and structural crises that the Augustan principate had got into a crisis. The principate ended at the latest in AD 284 when Diocletian introduced the tetrarchy against autocracy and put together a package of basic administrative, economic and social reforms.

The Imperial Administration of the Imperial Era

The establishment of a powerful Reich administration is to be emphasized as an achievement of importance. It consisted of adequately paid professional civil servants who came primarily from the senatorial and knighthood (eques romanus) . The provincial governors performed the duties of their offices under imperial central administration. The central authorities of the princeps were mostly occupied by reliable and educated imperial freedmen and slaves , from Hadrian onwards by members of the equestrian order. Correspondence was still conducted by the imperial chancelleries a memoria (personnel office, appointment decrees ), ab epistulis ( inquiries from officials) and a libellis (entries from private individuals). The tax administration was basically split into the imperial fiscus and the aerarium administered by the senate . For the most important offices of the city prefect and the Praetorian prefect , only senators or knights came into consideration a priori.

Position on Christianity

The Christian was that for decades by the Romans considered Jewish sect (to about 130 n. Chr.), Initially up to localized persecution tolerated meantime even legally protected. Since Caesar, the Jews enjoyed religious freedom in principle .

From the middle of the 3rd century onwards, however, the persecution of Christians as a whole began, which reached its peak under Diocletian between AD 303 and AD 311. According to the Four Emperor Regiment , state and religion were inseparable and Christianity's claim to exclusivity (“Christ is Lord”) was incompatible with the state imperial cult. After the edict against the revealed religion of the Manichaeans (probably before 302 AD), an edict was issued in 303 AD that barred Christians from access to public offices, forbade their worship services, ordered the destruction of their houses of worship and their holy scriptures (see Martyrs of the Holy Books ) and ultimately voided their civil rights.

The persecutions did not end until 313 AD with the Milan Agreement between Constantine the Great ( Western Emperor ) and Licinius ( Eastern Emperor ). The Constantinian turning point led to the abolition of the imperial cult. But it was only Theodosius the Great who finally ensured the recognition of Christianity as the state religion in the form of the " orthodox " imperial church with his term of office (380–391 AD) .

Special features relevant to constitutional law and politics during the principate

A variety of laws were created during the imperial era. For the simple legal order of life, Augustus took up the catalog of laws of his great-uncle Caesar, the leges Iuliae . In particular, he added family and penal regulations. The lex iudiciorum publicorum et privatorum regulated procedural, criminal and private law provisions, including functional jurisdiction. Sanctions for breaches of marriage and marriages outside of professional ethics were regulated with the lex de adulteriis coërcendis and the lex de maritandis ordinibus . Since Augustus was particularly concerned with family law, he decreed the leges Iulia and Papia Poppaea , which he used to fight marriage and childlessness. Around the turn of the ages, slave law regulations for the regulation of releases followed , such as the lex Fufia Caninia and, based on this, the lex Aelia Sentia . The authorship of the lex Petronia is unclear, the slave protection regulation was introduced during the 1st century. The Roman jurists had not developed a theory of customary law, which is why a legal sentence describes its historical origin, but not the current reason for validity. The “given” law, as it were , had to be further developed through interpretatio .

During Tiberius' term of office there are a total of 60 majesty trials. A sudden increase was due to the extensive judicial practice of the indefinite legal term "laesa maiestas" ("injured sublimity").

Caligula's successor, Claudius, was interested in law and justice. With doubtful success, however, he was happy to preside over litigation himself. Up to 20 ordinances were passed back to him daily, including medical and moral advice. His relationship with the Senate sometimes assumed conspiracy-like features.

Nero first made a name for himself as a sovereign judge who picked up on Augustus' traditions. For a long time he maintained a good relationship with the Senate, whose independence he supported in the case law. Ultimately, however, this turned out to be bad.

Galba , emperor of the first four emperors , led the army to discipline with iron measures. In the case of violations, sanctions could be imposed solely on the basis of his imperial authority. But despite the severity associated with his regime, this was the first time since the end of the republic that uniform penalties were administered, which is why soldiers in the Roman army could enjoy a certain degree of legal security. The military jurisprudence had previously been based solely on freely interpretable and unwritten customary law.

The cautious and modest founder of the Flavian dynasty, Vespasian , pursued internal (fiscal) security policy with his pax Flavia . Under him, Hispania received Latin citizenship (ius Latii) , a preliminary stage to Roman citizenship. His inauguration law of 69 AD, the lex de imperio Vespasiani , is considered to be an important legacy. His position of power manifested itself in the imperium proconsulare maius and in the tribunicia potestas , special powers already held by Augustus, Tiberius and Claudius. Like his father Vespasian, Titus was a celebrated ruler. The Jewish war was his dynastic legitimation .

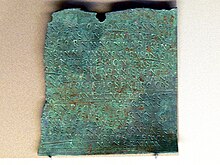

In Domitian's era, the bronze tablets of the leges Salpensana , Irnitana and Malacitana , which perpetuated Hispanic city rights, fall . Domestically, he vigorously fought corruption, ensured more efficient administration and consolidated state finances, but also made a name for himself through his reign of terror.

Hadrian fixed the edictum perpetuum and thus gave the judiciary an important impetus. The regulations in the Roman Forum in front of the praetor's official residence at the beginning of his term of office were published on white wooden boards .

Marcus Aurelius paid special attention to the weak and disadvantaged in Roman society. He tried to ease the situation for the slaves, women and children. Most of the legislative acts of the “philosopher on the imperial throne” aimed to improve the legal position of the weak. In accordance with his concerns in the legislative initiative act, he acted as the highest judicial body, an office that he exercised meticulously and with stoic composure.

Under Septimius Severus the signs of an economic crisis increased, so that the question arises as to whether he delayed the "Imperial Crisis of the 3rd Century" or rather helped to trigger it. Domestically, he operated the elimination of the Senate because he relied on the knighthood in administration and the military.

According to current research, 427 ordinances (constitutiones) can be traced back to Severus Alexander , contained in the Codex Iustinianus . In his legislation, especially in the years 223/4, he reflected on the emphasis on moral principles and stricter sanctions law in the event of breaches of the rules, with which he corrected the sometimes despotic legal practice of his Severan predecessors.

Maximinus Thrax is considered the first soldier emperor of the High Imperial Era , because he relied on the military, which completely marginalized the Senate.

The Principate's heyday and decline

The principate ensured a peaceful domestic existence ( Pax Romana ) and a significant cultural boom for the Roman Empire for two and a half centuries . Since the economy also grew moderately on average , bottlenecks occurring in some places of the expanding empire could be absorbed. The imperial government certainly did not pursue any economic policy, but it set a regulatory framework for free market interests through state budget policy and tax collection. Very different findings have been made in research on this. In 212 AD, Emperor Caracalla granted all free inhabitants of the empire Roman citizenship based on the decree of the Constitutio Antoniniana . Citizenship entitles them to both active and passive suffrage in popular assemblies. Cassius Dio insinuated Caracalla, however, that he had issued the regulation for the collection of higher taxes. Ulpian , previously Gaius, emphasized that constitutiones , which were mostly edicts (throughout the Julio-Claudian dynasty), decrees or rescripts (increasingly since Vespasian), were the central form of legislation in addition to the senate resolutions in the imperial era. The bourgeois legal inquiries were mostly processed by the imperial secretariats “ a libellis ” and “ab epistulis”, occasionally lawyers legitimized by the emperor answered .

The republican constitutional tradition did not allow the imperial office to be tied to a succession, which led to problems in determining successors. The principate's emperors made use of a trick. Suitable candidates were chosen during their lifetime and immediately appointed co-regents. If there were no descendants, or if the descendants were deemed unsuitable for entrusting government affairs, they were ousted by adoptives . Legally elected emperor as a child, Trajan , Hadrian , Antoninus Pius and Marc Aurel ascended the imperial throne ("Age of the Good Emperors"). In parallel with this procedure, the Senate was deprived of its influence on succession regulations. Dynasty founder Septimius Severus , in a certain sense the first military dictator, was able to stabilize the empire again with the help of legionary discipline . The army men, however, often had to be made compliant with gifts in order to prevent them from not enforcing their own ideas of political responsibility. The successor emperors succeeded less and less and there was a growing loss of control over the troops.

From 235 AD the empire fell into a crisis that quickly grew and lasted for over half a century. The crisis was triggered economically insofar as the money for a productive warfare ran out at all politically relevant borders. This was clearly noticeable during the clashes with the Parthians and the Teutons . Looting campaigns, revolts and devastation were the order of the day. The crisis was also a political one, because the emperors stayed with their troops on a regular basis, while Rome, the head of the empire, was orphaned and increasingly lost its importance. War generals seized the opportunity and vied for imperial dignity. Ultimately, the crisis was also of a legal cultural nature, because the regulatory framework that was owed to classical jurisprudence came to a standstill. There were no longer any courageous representatives of the once predominant schools of law . The intellectual quality of the early and high-class lawyers was sorely missed. Even the late classical attempts to exert a decisive influence on the legal system by emphasizing the citing lawyers threatened to come to a standstill. Ultimately, the vulgar legal compilations of late antiquity protected the regulatory framework insofar as the massive legal problems of understanding could be remedied at least to some extent. Today, however, research puts many aspects of the criticism of vulgar literature into perspective.

The constitution of late antiquity