Nika Uprising

The Nika Rebellion ( Ancient Greek ἡ Στάσις τοῦ Νίκα ) was a popular uprising in Constantinople in 532 during the reign of the Eastern Roman Emperor Justinian . The rebellion is considered the most serious circus riot of late antiquity ; during its course numerous people died and large parts of the city were destroyed.

causes

The trigger for the uprising was Justinian's surprisingly strict course against the circus parties, which stood in stark contrast to his promotion of the "Blue" faction before his rise to the throne .

The background to the unyielding attitude of the emperor, as a farmer's son a social climber, was probably that he saw himself more than his predecessors as a " ruler by the grace of God ". After the Eastern Roman troops were defeated by the Persians at the Battle of Callinicum in the autumn of 531 , Justinian's reputation was damaged and he responded by attempting to consolidate his authority through steadfastness and toughness. However, his idea of empire met with resistance , especially among the senators . And even the common people, in turn, do not seem to have accepted the legitimacy of the Justinian dynasty: 14 years earlier, Justinian 's uncle and predecessor Justin I had surprisingly become emperor, although the deceased Augustus Anastasius had had adult nephews capable of governing, who then died during the uprising in 532 played an important role.

Apparently, Justinian's ambitious plans and the war against Persia prompted him to adopt a rigid tax policy, which affected both the common people and – unlike under his predecessors – the ruling classes. Leading the way was Justinian's powerful praefectus praetorio Orientis , John the Cappadocian , who was therefore met with popular anger and contempt by the ancient elites. However, it is unclear whether these measures, which only took full effect in the years that followed, played a decisive role as early as 532.

course

The description of the course of the uprising is based on the information in the sources, in particular on the report of the eyewitness Prokop , whose report, however, is literary and biased. See the Reception section for interpretation options .

foreplay

In the run-up to the uprising, several troublemakers – partisans of the circus factions – were sentenced to death . After the first executions had been carried out, the gallows or the rope failed several times in the case of two delinquents , which the people present saw as a sign from God . The two men were asked to be pardoned , but this was denied by the responsible authorities. This turned out to be disastrous, since the two convicts were each attributed to the enemy circus parties, which now developed a common interest. In the ensuing uproar, the enraged crowd supported a group of monks who took the condemned to the shelter of a monastery.

riots

Three days later, on January 13, the usual circus games for the Ides were held in the hippodrome in the presence of the emperor . After 22 runs, the circus parties began to demand the release of the two prisoners. When Justinian did not reply after a long time (a very unusual behavior for a late antique emperor), the outrageous acclamation "To the people-loving blue and green many years!" rang out. The warring factions had thus united against the emperor. The word "Nika" (νίκα, "victories!"), which gave the survey its name, was used as a password among each other. As a result, there was an attack on the praetorium of the city prefect on the same day .

Presumably to give an impression of normality and to reassure the people, the January 14 races were not canceled. However, the crowds that gathered in the Hippodrome soon ramped up again, with the wooden benches of the Hippodrome and the arcades of the main street all the way to the Baths of Zeuxippus bursting into flames. In response, the remaining units loyal to the emperor under Mundus , Constantiolus and Basilides took brutal action against the insurgents.

political protest

In the course of the unrest, the first demands of the insurgents became known: the dismissal of the praetorian prefect John , the city prefect Eudamion and the quaestor sacri palatii Tribonianus , the emperor's chief jurist. Justinian complied with these demands and dropped the three high dignitaries for the time being; nevertheless, the riots continued. Thereupon the commander Belisarius , who had just returned from the war with the Persians and who was supposed to answer to Justinian for the defeat at Kallinikon, took action against the rebels with his large bodyguard , but was unable to record any resounding success.

Open Uprising

In the meantime, the unrest had turned into an open uprising, the outcome of which was still completely open. On the night of January 14 to January 15, the Chalke, the Senate Curia, the quarters of the palace guards of the scholarii , protectores and candidati , the Imperial Forum ( Augusteum ) and the predecessor church of Hagia Sophia were set on fire in the palace quarter . The fronts had hardened and the Emperor is said to have thought of fleeing. It is possible that a speech by Empress Theodora I , handed down by Procopius , of very questionable authenticity, calling on Justinian to be strong and persevere, fell into this phase.

In this phase at the latest, the rebels began to toy with the idea of a new emperor. Thus, on January 15, a crowd marched to the house of Probus, a nephew of the former Emperor Anastasius , and, shouting "Probus, Emperor for Rome!", demanded arms for the rebels. When there was no answer, they set the house on fire. On January 16, insurgents vandalized the Praetorium archives, probably to destroy incriminating criminal files. The fire which they set spread through an unfavorable wind and burned the church of Hagia Eirene , the baths of Alexander, two imperial villas, the basilica of Illus and the hospice of Samson and Eubulus.

Since the Palace Guard troops remained neutral, Justinian had apparently summoned more troops from the nearby garrisons of Hebdomon, Rhegio, Athyras and Calabria, who clashed with the insurgents on January 17. In the process, parts of the building called the Octagon , the Porticus of the Silversmiths, the House of Symmachus, the Churches of St. Aquilian and St. Theodore, and an arch on the Forum of Constantine burned . In another action, Liburnon and Magnaura were set on fire. The result of the ensuing street and house fighting was a draw. At the latest since the new troops were in the city, it was probably only a matter of time before the uprising was crushed.

On the morning of January 18, Justinian summoned the people to the hippodrome and offered those involved in the uprising immunity. At first the people seemed to agree, but then the mood changed when the rumor spread that Justinian had already fled the city, and Hypatius , another nephew of Anastasius, was proclaimed anti-emperor at the Forum of Constantine with the participation of several senators.

crackdown

The role of Hypatius cannot be definitively clarified. According to Procopius, after his insurrection, he tried to secretly contact Justinian and submit to his mercy, but then the false news that Justinian had fled on a boat was the decisive factor in Hypatius finally accepting his (tragic) role. It is more likely, however, that Hypatius, as a candidate for the senatorial opposition, deliberately wanted to use the uprising to gain power, and that Procopius tried in his report to protect the usurper afterwards.

In the meantime, however, the court chamberlain Narses had succeeded in bribing parts of the Blues in favor of Justinian. confusion broke out. The troops loyal to the emperor under Belisar, Mundus and Constantiolus then entered the hippodrome at several points at the same time and began a massacre that probably killed 30,000 people, as thousands were trampled during the panic that broke out. The following day, Hypatius and Pompey , who had been arrested with him, were executed and their bodies thrown into the Sea of Marmara . Justinian later had the surviving rebel leaders paraded in a victory parade at the Hippodrome. Only some time later did he show clemency and returned the property that had been confiscated to the family of Pompeius and Hypatius.

Follow

All in all, the rigorous crackdown on the insurgents strengthened the Kaiser and disempowered the already very weak senatorial opposition. On the other hand, Justinian remained hated by the urban population and parts of the Senate for a long time. The influence of Belisarius , Narses and above all Theodora was obviously strengthened, and they became particularly prominent politically in the period that followed. Belisarius, previously disgraced by his defeat at the hands of the Sassanids , regained Justinian's favor for his loyalty to the emperor, and was put in charge of the military expedition against the Vandals the following year . Narses, his rival, also remained highly influential in the decades that followed.

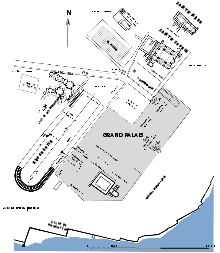

The destruction caused by the uprising in Constantinople also offered Justinian the opportunity for ambitious building projects in the capital, in the course of which the devastated and burned Hagia Sophia in particular was rebuilt. After the events of the Nika Uprising, chariot races were initially no longer held in the hippodrome in the years that followed.

reception

Despite or precisely because of the relatively dense source material on the Nika uprising provided by the eyewitnesses Prokop and (perhaps) Johannes Malalas , there are several interpretations among historians. While Alan Cameron , at least in the initial phase, saw a typical late antique unrest emanating from the circus parties, historians in the former Eastern bloc mostly assumed a purely spontaneous popular uprising. Recently, it has been repeatedly suggested that some senators can be identified as the driving force behind the insurgents from the outset, as the eyewitness Marcellinus Comes also expressly reports; however, Marcellinus thus reflects the official reading of the events.

Another, but very controversial theory even sees Justinian himself as the originator, who wanted to use the uprising to be able to eliminate the unloved opposition : Contrary to Geoffrey B. Greatrex 's assessment , Mischa Meier assumes that the catastrophe was not caused by a "snaking course ", that is, an insecure communication strategy of the emperor, but by a targeted escalation: Justinian found his enemies through the provocation of the circus parties, the intrigue around Hypatius, Anastasius' nephew, and the false news of the emperor's flight want to tempt him to come out of cover and expose himself, because in this way he wanted to get rid of his opponents in the upper class. However, Meier's hypothesis has so far not been able to establish itself in research.

In addition, the so-called Akta diá Kalopódion are a point of contention for historians. In this description of a dispute between the circus parties and Justinian in the hippodrome near Theophanes , it is disputed whether a connection with the Nika rebellion can really be established.

sources

- Procopius of Caesarea , " Wars ", 1:24; " Secret History ", chap. 7.

- Johannes Malalas : " World Chronicle ", 18, 473ff.

- Marcellinus Comes : ad annum 532

- Anonymous: " Chronron Paschal ", Olympiad 327.

- Theophanes : "Universal Chronicle", 181.24-186.2.

literature

- Joanna Ayaita: Justinian and the People in the Nica Rebellion . Dissertation, Heidelberg 2015.

- Hans-Georg Beck : Empress Theodora and Prokop. The historian and his victim (= Piper 5221). Piper, Munich et al. 1986, ISBN 3-492-05221-5 , pp. 35-40 [In line with his topic, Beck emphasizes Theodora's alleged increase in power after the uprising].

- John B Bury : The Nika Riot. In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies . Vol. 17, 1897, pp. 92–119, doi:10.2307/623820 , online – Internet Archive [This article, written 100 years before Greatrex, is still worth reading and recommendable due to its comparison of sources].

- Alan Cameron : Circusfactions. Blues and Greens at Rome and Byzantium. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1976, ISBN 0-19-814804-6 [Cameron's book serves as a basis for analyzing events involving the circus parties. In the chapter "Two special cases" (pp. 278-281) he goes into more detail about the Nika uprising. At least at the beginning he classifies it as a typical uprising of the circus parties].

- James AS Evans: The 'Nika' Rebellion and the Empress Theodora. In: Byzantium. Vol. 54, 1984, ISSN 0378-2506 , pp. 380-382.

- Geoffrey B Greatrex : The Nika Riot: A Reappraisal. In: The Journal of Hellenic Studies. Vol. 117, 1997, pp. 60-86, doi:10.2307/632550 [Greatrex examines in great detail, in particular, the changing dynamics during the course of the uprising].

- Mischa Meier : The staging of a catastrophe: Justinian and the Nika uprising. In: Journal of Papyrology and Epigraphy . Vol. 142, 2003, pp. 273-300 [Meier's theses are controversial in research. He sees the uprising as an act deliberately staged by the emperor, through which Justinian stabilized his rule and got rid of unwelcome competition].

- Franz H. Tinnefeld : The early Byzantine society. Structure - opposites - tensions (= critical information. Vol. 67). Fink, Munich 1977, ISBN 3-7705-1495-5 , pp. 83-85 and pp. 194-199 [Tinnefeld thinks that the secret opposition from Senate circles came to light in the Nika uprising].

web links

- Procopius' account of the Nika uprising

- The Akta diá Kalopódion (English)