Zeuxippus thermal baths

The Baths of Zeuxippus were public baths in the Byzantine city of Constantinople . They were built in the 2nd century AD, destroyed during the Nika uprising in 532, and rebuilt a few years later. The thermal baths were built around 450 meters south of the older baths of Achilles in the Acropolis of Byzantion . The subjects were best known for their many statues depicting famous people. In the 7th century the thermal baths were then used for military purposes.

location

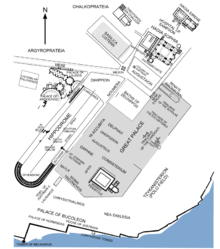

The baths of Zeuxippus were located north of the Great Palace of Constantinople between Augustaion and the northeast corner of the Hippodrome. The Byzantine historian Johannes Zonaras told in the 12th century how Septimius Severus built the baths on the foundation walls of a Jupiter temple and connected it to the hippodrome . The theologian Leontios of Jerusalem , whose descriptions were considered more accurate and appeared before Zonaras' writings, claimed, however, that the baths were not built on the hippodrome, but were located nearby.

Surname

The origin of the name of the topics is unclear. The bathhouse is said to get its name from the place where it was built, where originally there was a cult site for Helios, who was often equated with Zeus . There could also have been a statue of Zeus or paintings by the Greek painter Zeuxis of Herakleia (also Zeuxippus of Herakleia ).

History and description

The baths were built by Septimius Severus in the 2nd century AD and expanded and decorated under Constantine the Great in 330. Numerous mosaics, paintings and more than 80 statues were installed, most of them depicting important historical figures such as Homer , Hesiod , Plato , Aristotle and Julius Caesar . These statues were brought in from all over Asia Minor, Rome and Greece . The baths thus followed a contemporary architectural trend: buildings such as the Senate Palace, the Forum, the Lausus Palace were all adorned with similar statues of mythological heroes, historical figures and important personalities. The Zeuxippos thermal baths were richly encrusted with colored marble, Kroke stone , Rosso Africano and Giallo Africano. A frieze with dolphins and nereids in proconnesian marble refers to a decoration with marine motifs.

For a very small fee, anyone could use the bath complex. While the area was obviously primarily used as a public bathing establishment, there were also other opportunities for recreation. In addition to the actual thermal bath building, there was a large open peristyle that belonged to a grammar school . So it was probably gymnasium thermal baths: vaulted rooms alternated with open rectangular areas for exercises.

Bath attendants monitored the complex, took care of opening times and compliance with the rules. Women and men were not allowed to bathe together. They were either housed in different parts of the building or bathed at different times.

The Zeuxippus thermal baths were well known among the citizens, although at that time there were some bath houses in the city and so there was great competition. Even clergymen and monks were seen there, although their superiors scourged the baths as places of ungodly behavior.

During the Nika uprising in 532, large parts of the city were destroyed and thousands of people died. The baths of Zeuxippus were also destroyed by fire. Emperor Justinian I rebuilt the themes, but the ancient statues were destroyed and were never put back up.

At the beginning of the 7th century, public bathing changed from an everyday ritual to a rare luxury due to extreme military and political pressures on the Byzantine Empire. Many public facilities and venues have been converted for military purposes. The thermal baths of Zeuxippus were last mentioned as a bath house in 713 before being remodeled for other purposes: part of the building became the prison known as Noumera , while another part served as a silk workshop .

In 1556, the Ottoman architect Sinan built the Haseki Hürrem Sultan Hamamı on the same site. In 1927/28 excavations were carried out on this site and many historical relics such as earthenware and glazed ceramics were recovered. This enabled insights into the architecture, but also into the social interests of the people and the culture of Constantinople. A special find were two statues that were inscribed with the words Hekabe and Aeschenes [sic!] On their bases.

Reception in literature

The late antique poet Christodoros wrote a 416 line long poem in hexameters , which was inspired by the magnificent statues of the thermal baths. It consisted of six short epigrams , each of which referred to a small group of the statues. It has been suggested that the epigrams of Christodorus were inscribed on the bases of the statues, but this is unlikely due to the descriptive language and the use of the past tense.

literature

- Carlos A. Martins de Jesus: The statuary collection held at the baths of Zeuxippus (Ap 2) and the search for Constantine's museological intentions . Synthesis, Vol. 21, 2014 ( digitized version )

Web links

- Reconstruction , Byzantium 1200 project

Individual evidence

- ^ A b c Bryan Ward-Perkins: The Cambridge Ancient History: Empire and Successors, AD 425-600 . Cambridge University Press, 2000, p. 935

- ↑ Pero Tafur: Travels and Adventures 1435-1439 . Routledge, 2004. p. 225

- ^ A b Pierre Gilles : The Antiquities of Constantinople . Italica Press, Incorporated 1998, ISBN 0-934977-01-1 , p. 70

- ↑ Alessandra Bravi: Old sculptures in a new urban space for Konstantin . In: Greek works of art in the political life of Rome and Constantinople . (= Volume 21, KLIO - New Series Contributions to Ancient History), April 2014, p. 250

- ↑ Alessandra Bravi: Kaiser, Volk and Oikumene: from the thermal baths of Zeuxippos to the hippodrome . In: Greek works of art in the political life of Rome and Constantinople . (= Volume 21, KLIO - New Series Contributions to Ancient History), April 2014, p. 270

- ^ A b c John Bagnell Bury: A History of the Later Roman Empire from Arcadius to Irene (395 AD - 800 AD) . Adamant Media Corporation, 2005, ISBN 1-4021-8369-0 , p. 55

- ↑ Alessandra Bravi: Kaiser, Volk and Oikumene: from the thermal baths of Zeuxippos to the Hippodrome In: Greek works of art in the political life of Rome and Constantinople . (= Volume 21, KLIO - New Series Contributions to Ancient History), April 2014, p. 269

- ↑ Stephan Busch: VERSUS BALNEARUM. The ancient poetry about baths and bathing in the Roman Empire . De Gruyter, Oldenbourg 1999, p. 314

- ↑ James Allan Stewart Evans : The Age of Justinian: The Circumstances of Imperial Power . Routledge, 1996, ISBN 0-415-02209-6 , p. 30

- ^ Ferdinand Gregorovius, Annie Hamilton: History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages . P. 80

- ↑ Alessandra Bravi: Kaiser, Volk and Oikumene: from the thermal baths of Zeuxippos to the hippodrome . In: Greek works of art in the political life of Rome and Constantinople . (= Volume 21, KLIO - New Series Contributions to Ancient History), April 2014, p. 271

- ↑ Alessandra Bravi: Kaiser, Volk and Oikumene: from the thermal baths of Zeuxippos to the hippodrome . In: Greek works of art in the political life of Rome and Constantinople . (= Volume 21, KLIO - New Series Contributions to Ancient History), April 2014, p. 270

- ^ A b c Marcus Louis Rautman: Daily Life in the Byzantine Empire . Greenwood Press, 2006, ISBN 0-313-32437-9 , p. 77

- ^ William Matthews: An historical and scientific description of the mode of supplying London with water . 1841, p. 230

- ^ Edward Gibbon: The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire . Penguin Classics, 1995, ISBN 0-14-043394-5 , p. 950

- ↑ a b c Alexander Kazhdan : Zeuxippos, Baths of . In: Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium . Oxford University Press, 1991, ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6 , p. 2226

- ↑ Demetra Papanikola-Bakirtzis: Zeuxippus Ware: Some Minor Observations . In: British School at Athens Studies , Vol. 8, MOSAIC: Festschrift for AHS Megaw (2001), pp. 131-134

- ^ A b Scott Fitzgerald Johnson: Greek Literature in Late Antiquity: Dynamism Didacticism Classicism . Ashgate Publishing, 2006, ISBN 0-7546-5683-7 , p. 170

- ↑ Glen Warren Bowersock , Peter Brown, Oleg Grabar: Late Antiquity A Guide to the Postclassical World . Harvard University Press, p. 6

Coordinates: 41 ° 0 ′ 23 " N , 28 ° 58 ′ 33" E