Augustaion

The Augustaion (Greek Αὐγουσταῖον , Latin Augusteum or Augusteion ) was a place in Constantinople , which existed from its construction during the reign of Emperor Septimius Severus (193–211 AD) to its demolition in the 16th century. Originally the place was known as Opsopoleion (gr. Όψοπωλεῖον ) or as Tetrastoon (gr. Τετράστοον ). The first mention of the name Augusteum comes from a regional directory at the beginning of the 5th century. He refers by name (in Latin augustus , emperor or imperial) to statues of the emperors Constantine the Great and Theodosius I.

location

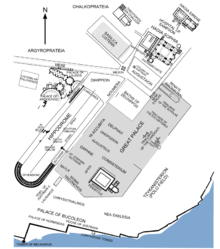

The square adjoins the Hagia Sophia to the southwest and is known for the Justinian column that used to stand there . In Roman times, the Augustaion was originally outside the city walls.

history

The square was built during the rebuilding of Byzantium during the reign of Septimius Severus. In the 4th century the square was clearly delimited by the Mese running south , the main street of Constantinople, by the construction of the temples of Tyche and Rhea in the west and the construction of the Senate building in the east and the Church of St. Sophia in the north. Emperor Constantine the Great had a statue of his mother Helena , which was titled Augusta , and Emperor Theodosius I put up a silver statue of himself in the square .

During the tenure of City Prefect Theodosios (459) the Augustaion was expanded and the colonnades surrounding the square were probably built. At the time of Emperor Justinian I , the neighboring buildings were destroyed by fires during the Nika uprising (532). In addition to the nearby Hagia Sophia , Emperor Justinian also had the Augustaion renovated and expanded: he had the square paved with slabs, surrounded by two-story hall buildings and the statue of Thesodosius I replaced by the 35-meter-high Justinian column . In the 7th century an official building of the Patriarch of Constantinople was built on the southeast side, which existed until the 16th century. Around 1200 the gates of the Augustaion were destroyed during the revolt of the opposing emperor Johannes Komnenos . In the 13th century the Augustaion was plundered and largely devastated in the course of the sacking of Constantinople (1204) in the Fourth Crusade by the Crusaders. After Constantinople was recaptured in 1261 , the Augustaion was incorporated as the forecourt of Hagia Sophia. After a storm in 1316, Emperor Andronikos II ordered a restoration of the square and the Justinian column.

In the last few years of the Byzantine Empire , the place was pretty rundown. After the conquest of Constantinople in 1453 , the head of the last emperor Constantine XI is said to be on the Augustaion on the Justinian column . have been issued. During the Ottoman period, the statues were removed in the course of the 15th and 16th centuries and the square was built with a cistern and doorways from Ottoman sultans. So the use as a plaza ended.

function

The square originally served as the economic center of Byzantion. Later, the square played an important role as a place of public life in Constantinople, making it the center of the city for a long time thanks to its location between the Imperial Palace, Hagia Sophia, the Zeuxippos Baths and its proximity to the hippodrome . Prokopios of Caesarea calls the Augustaion the Agora , which indicates that in the time of Justinian I the square was still the central festival, market and meeting place. After the Augustaion was walled during the restoration work after the Nika uprising, the Augustaion was increasingly closed to the public. In the post-Justinian period, the square was mainly used as an imperial and ecclesiastical place to hold ceremonies. After the reconquest of Constantinople in 1261, the Augustaion only served as the forecourt of Hagia Sophia, but was a central venue for festivities until its end.

literature

- Franz Alto Bauer : town, square and monument in late antiquity. Investigations into the furnishing of public spaces in the late antique cities of Rome, Constantinople and Ephesus . Mainz 1996, ISBN 3-8053-1842-1 .

- Peter Schreiner : Constantinople. History and archeology (= CH Beck Wissen , Volume 2364). CH Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-50864-6 .

- Otto Veh : Buildings (= Prokopios of Caesarea: Works , Volume 5). Heimeran, Munich 1977, ISBN 3776521090 .

- Wolfgang Müller-Wiener : Pictorial dictionary on the topography of Istanbul. Byzantium - Constantinople - Istanbul until the beginning of the 17th century . Wasmuth, Tübingen 1977, ISBN 3-8030-1022-5 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Wolfgang Müller-Wiener: Pictorial dictionary on the topography of Istanbul . Tübingen 1977, p. 249f.

- ^ Franz Alto Bauer, City, Square and Monument in Late Antiquity . Mainz 1996, p. 148.

- ↑ Wolfgang Müller-Wiener: Pictorial dictionary on the topography of Istanbul . Tübingen 1977, p. 248.

- ^ Prok., Aed., I, 10.

Coordinates: 41 ° 0 ′ N , 28 ° 59 ′ E