Edo

Edo ( Japanese 江 戸 ), literally: “River gate, mouth”, also written Jedo , Yedo or Yeddo in older western texts , is the former name of the Japanese capital Tokyo . It was the seat of the Tokugawa shogunate , which ruled Japan from 1603 to 1868, and named this period in Japanese history the Edo period . During this time Edo grew into one of the largest cities in the world.

The town

The beginning

Edo was first mentioned as a field name in 1261. In 1456 Ōta Dōkan , a multi-talented general, built Edo Castle on a hill and made the place the center of his activities. After his violent death in 1486 the castle fell into disrepair.

Edo as a castle town

When Tokugawa Ieyasu took control of the provinces around Tokyo Bay in 1590 as part of an exchange of territory , he decided to make the insignificant Edo his headquarters. He restored the well-located castle and began to expand it. In these troubled times it was important to secure yourself and your family first. The hilly area, on the other hand, was not particularly suitable for the layout of a large city. But as was customary with the castle towns of the time, he settled his followers at the castle , before the craftsmen and traders.

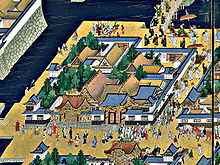

After Ieyasu had defeated the competitors for rule over Japan in the Battle of Sekigahara in 1600 , he was appointed Shogun by the Tennō in 1603 . Edo was now the political center of Japan, Kyoto remained the formal capital of the country as the seat of the Tenno. The large-scale castle, surrounded by the "Inner Ditch" (Uchibori) with its branch ditches and more than 20 gates, was supplemented by the "Outer Ditch" (Sotobori) with 10 gates. The gates were box-shaped (see Fig. Babasakimon): you first entered an inner courtyard through a small gate, which could be locked before the mighty main gate - usually built at right angles to it - was opened.

The city expanded significantly before the Outer Rift and occupied an area that is now enclosed by the Yamanote Line , to which the areas beyond the Sumida were added. "Yamate / Yama-no-te" d. H. "Mountain side" (山 手 / 山 の 手) refers to the hills in the west and north of the city. In this area, the urban structure is determined by the fact that roads were laid along the heights or along the valleys and that these were connected by hillside paths (sakamichi). Many sakamichi had (nick) names, which are remembered today with inscribed wooden pillars.

The plain towards the sea (including the areas extracted from the sea) formed the "lower town" ( 下町 , shitamachi). As with all castle towns, there was no final city wall. Two gates, the “Takanawa Ōkido” (on the Tōkaidō ) and the “Yotsuya Ōkido” (on the Kōshū Kaidō ) marked the approximate beginning of the city, but were not used for defense purposes.

The daimyo and their residences

In order to consolidate power, the " sankin kōtai " law was passed in 1635/42 . This regulation obliged all daimyō (feudal lords) to maintain a permanent residence in Edo and either to be present themselves or to leave parts of their families there as hostages of the Shogun. The residence was surrounded by a high wall, often combined with the dwellings for the simple servants, the nagaya . Opposite the entrance gate was the prince's work and reception area ( goten, omote ), behind which was the supply area ( oku ) managed by the princess . The residence belonged still building for the next employee, usually a garden (some of which have received), often a Noh -Bühne. In size and design, the reflected the income of the daimyo. The construction and operation of the residences brought a lot of capital into the city and attracted traders and craftsmen. Edo grew steadily and the unknown fishing village of 1457 became the largest city in the world - with a million inhabitants.

Temples and shrines

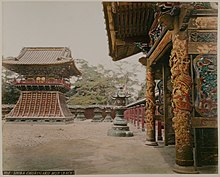

The Sensō-ji traces its foundation back to the year 628, when fishermen found a small golden Kannon figure in their net, and as a result the temple was built in 645 - at that time far outside of later Edo. The Sensō-ji has been able to maintain its closeness to the people to this day. Most of the temples later in Edo were more associated with the sword nobility. For example, when Tokugawa Ieyasu first arrived in Edo in 1590, he visited the Zōjō-ji , whose monks received him so well that he made it a burial temple (bodai-ji) for his family. As the burial temple of the shoguns next to the Zōjō-ji, the Kan'ei-ji, built in 1625, played a special role. Located in the northeast of the city, which was considered a dangerous direction in traditional Onmyōdō ( cosmology / geomancy ), the temple also protected against evil spirits. With the arrival of the samurai and the daimyo becoming resident, many temples were built in all parts of the city. The Sengaku-ji , which was built in 1612 and became the burial place of the 47 samurai and their master in 1701/03, became famous .

The people who were more inclined to Shinto visited his shrines. They were more modest than the temples, but famous for their parades. In the Edo period it was mainly the Hie-jinja , called Sannō-matsuri, but also such a festival on the Kanda Myōjin . The shrines of Yushima Tenman-gū and Kameido Tenmangū on the eastern edge of the city were dedicated to the scholar Sugawara Michizane . Ieyasu, who is buried in the distant Nikkō, has two small shrines, Tōshōgū , dedicated in Edo, the one on Ueno Hill having survived all earthquakes, the Boshin War and World War I and is one of the oldest buildings in Tokyo.

The lower town

"Lower town" is to be taken literally: the flat areas facing the sea were mainly inhabited by townspeople - chōnin - ( 町 人 ), but there are also numerous daimyo residences. On the other side of the Yamanote area there were workers and craftsmen who were available for work in the residences (as so-called "goyō-kiki") along the streets and in the narrow valleys. The chōnin's offices were also to the right and left of the access roads .

Areas that were exclusively inhabited by chōnin are mainly Kanda, then the area north to Asakusa, where the old temple Sensō-ji marked the approximate end of the city. Another chōnin area was the former headland in front of the former Hibiya Bay: Ginza and Nihonbashi. The area beyond the Sumida River was crisscrossed with canals and settled by chōnin , but is interspersed with side residences of the daimyo.

Feudalism was evident in the distribution of the living space: according to a study from 1869, it looked like this: the sword nobility owned 69%, the temples and shrines owned 15%, the chōnin the remaining 16% of the area, on which there are 500,000 people huddled together. In the simple “nagaya” family, the poorest had only one sleeping place of 4½ tatami available.

City administration

The chōnin were ruled by two city commissioners ( 町 奉行 machi-bugyō ) who were directly subordinate to the chancellor ( 老 中 rōjū ) of Bakufu. They could make the laws that they would apply. They could speak right too and were so omnipotent. Among the commissioners there were certainly those who were accepted by the people as just and wise, such as B. the city commissioner Ōoka Tadasuke (1677–1751). The commissioners were in their work supports the so-called 25. Yoriki ( 与力 Yoriki ), where 100 Doshin ( 同心 Doshin ) were under, and other personnel, "feeder" spies (tesaki, meakashi, okappi). "City elders " ( 町 年 寄 machi-doshiyori ), who were supported by city "upper citizens " ( 町 名主machi-nanushi ), ensured order in everyday life .

The two city commissioners were on duty day and night every month ( 月 番 tsukiban ). They came from the Hatamoto stand and were rewarded with 3,000 koku . Some held this function until the end of their lives, some were replaced after a year. After the location of their residence they were usually "North Commissioner" ( 北 町 奉行 kita-machibugyō ) and "South Commissioner" ( 南 町 奉行 minami-machibugyō ) called, but they were each responsible for the entire city. Your area of responsibility, d. H. the city's border ( 御府 内 gofunai ) was kept secret so that criminals would not know when they were safe. It was only after 1868 that the boundaries of that time became generally known.

The place of the court hearings was called o-shirazu ( 御 白 洲 ), the big prison (rō-yashiki, also called rōgoku = prison hell) was located in the Kodemmachō district. For Christian missionaries who ended up in Japan after the country was closed and tried to continue their activities, there was a separate small prison in the Koishikawa district . The hillside path "Kirishitan-zaka" still reminds of this today.

The big fires

Edo has been repeatedly ravaged by fires, with the Great Meireki Fire in 1657, which killed an estimated 100,000 people, being the most devastating. The fire led u. a. to the following measures:

- The Gosanke residences were given land outside the "Outer Trench".

- All daimyo created secondary residences.

- The shogunate set up a professional fire brigade with firefighters (jōbikeshi).

The fires could not be avoided: Especially in January there was a great drought due to the weather, so even a small carelessness triggered a fire. In addition to countless small fires, there were ten major fires between 1600 and 1900. They are based on the current annual currency ( Nengō ), e.g. B. Meireki, but are often known by a special name. In 1718, the city commissioner Ōoka organized on the instructions of the Shogun Yoshimune a city fire brigade with part-time workers, which was divided into 64 brigades of different sizes (50-500).

Until there was a splash of water, the activity of the fire brigades was limited to tearing down houses to limit the spread of the fire. Occasionally too much was torn down, which led to the saying: “Fire and strife are the flowers of Edo” ( 火 事 と 喧嘩 は 江 戸 の 花 , Kaji to kenka wa Edo no hana).

In order to discover the fires early, watchtowers or lookouts were erected throughout the city, as can be seen on the Hiroshige print "Nihonbashi". Since the Japanese wooden houses were built in a standard size , due to the tatami , and building materials were kept in stock in large quantities, the houses could be restored quickly.

Water supply

Since wells were soon no longer sufficient, in the Keichō period water was carried from the inland Inokashira Lake via a 20 km long canal to Edo, which was reached in the Koishikawa district. From there it was led over the Sotobori with the help of a bridge and reached Kanda, from which it got its name, "Kanda jōsui" ( 神 田 上水 ). This water supply was in operation until 1903, until today the road bridge Suidōbashi, next to the now disappeared water pipeline bridge, reminds of the system.

Soon Kanda jōsui was no longer enough. In a private initiative, two brothers laboriously measured a canal route that made it possible to bring water from the Tama River to Edo, which was reached in Shinjuku, from a distance of 50 km with little gradient. From Yotsuya the water continued underground. This Tamagawa jōsui ( 玉川 上水 ) was not shut down until 1965. The water supply system was further supplemented by "Kameari jōsui" ( 亀 有 上水 ), "Aoyama jōsui" ( 青山 上水 ), "Mita jōsui" ( 三 田 上水 ) and " Sengawa jōsui "( 千 川 上水 ).

Economy and Transport

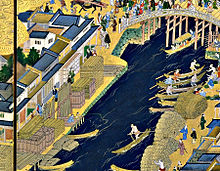

The supply of the city of Edo was taken over by a highly developed system of coastal shipping, which had different types of boats, Tarubune , Bezaisen or Sengokusen . The goods were loaded onto barges in Edo Bay and transported to the large shops that had warehouses, often in the form of fire-proof stores. The Mitsui family was very successful and called their large clothing store "Echigo-ya" ( 越 後 屋 ). An important commercial center of the city was on the Nihon Bridge ( 日本 橋 , Nihon-bashi ), the important bridge over the canal that led from the castle to the sea. The canal was lined with warehouses on both sides.

The state warehouses with the rice stores (see Koku ) of the Shogunate were located on the Sumida , then simply Great River ( 大川 , Ōkawa ) . This area on both sides of the river was called Kuramae ( 蔵 前 , in front of the warehouses ). On the eastern side were also the large stores of timber.

Goods also came to Edo by land, using the "Five Roads" ( Gokaidō ). However, there were restrictions: as a precautionary measure against uprisings, oxcart transports required a special permit, and for the same reason there were usually no bridges over the rivers.

Edo as an educational institution

First of all, the Bakufu educational institution should be mentioned:

- Shōheizaka gakumonjo had emerged from the school of Hayashi Razan . The school used buildings in the Yushima Seidō temple complex on the "Shōheizaka" hillside path, which is dedicated to Confucius .

There were also a number of private schools (juku) including:

- Kenenjuku, founded around 1709 by Ogyū Sorai (1666–1728). This school taught Confucianism and the study of ancient scriptures.

- Tenshinrō, founded around 1769 by Sugita Genpaku (1733–1817). Sugita taught Western medicine and Rangaku in general .

- Otowajuku, founded by Honda Toshiaki (1744–1821). Honda taught arithmetic ( wasan ) and economics.

- Shirandō, founded in 1786 by Ōtsuki Gentaku (1757–1827). Ōtsuki, a student of Sugita, taught Western medicine and Rangaku in general .

- Keiō gijuku , founded in 1858 by Fukuzawa Yukichi in the district of Teppōzu, the school was given this name after moving to Mita in Keiō 4. University since 1920.

Edo-born scholars and artists (selection)

It is noteworthy that all of the graves (almost all of today's Tokyo) have been preserved. Some are marked as "Historical Traces" ( 史跡 , shiato) at the national level, others at the urban level. (Order of persons according to date of birth.)

- Confucianists: Hayashi Hōkō (1644), Arai Hakuseki (1657), Muro Kyūsō (1658), Ogyū Sorai (1660), Kameda Hōsai (1752), Satō Issai (1772), Terakado Seiken (1796), Shionoya Tōin (1809)

- National doctrine : Katō Chikage (1735), Murata Harumi (1746), Shimizu Hamaomi (1776)

- Western science, medicine: Aoki Konyō (1698), Sugita Gempaku (1733), Katsuragawa Hoschū / Shinra Bonshō (1751), Udagawa Gensui (1755), Ōtsuki Bankei (1808)

- Haiku, Senryū : Sugiyama Sambū (1647), Takarai Kikaku / Enomoto Kikaku (1661), Karai Senryū (1718)

- Joke poems: Akera Kankō (1738), Karagoromo Kisshū (1743), Ōta Namba (1749), Ishikawa Masamochi (1753)

- Humorous stories: Utei Emba (1743), Koikawa Harumachi (1744), Santō Kyōden (1761), Takizawa Bakin / Kyokutei Bakin (1767), Shikitei Samba (1776), Ryūtei Tamehiko (1783), Tamenaga Shunsui (1790), Kanagaki Robun (1829)

- Ukiyoe: Katsukawa Shunshō (1726), Katsushika Hokusai (1760), Utagawa Toyokuni (1771), Keisai Eisen (1790), Utagawa Hiroshige (1797)

- Painter: Shiba Kōkan (1747), Sakai Hōitsu (1761), Tani Bunchō (1763), Watanabe Kazan (1793)

- Other: reconnaissance Hayashi Shihei (1738), Chancellor matsudaira sadanobu (1760), discoverer Kondō Juzo (1771), editor Kariya Ekisai (1775), calligrapher Ichikawa Beian (1779), Kabuki-author Kawatake Mokuami (1816), Rakugoka Sanyutei ENCHO ( 1839)

Popular city culture

The "Three Pleasures" of Edo, exemplified by prominent representatives on the adjacent woodcut, were kabuki , sumo and yoshiwara . All three amusements were under the supervision of the city:

- The Kabuki theaters were grouped towards the end of the Edo period in the northeast of the city in the Saruwaka-chō district.

- Sumō were held in shrines, which - like the temples - were under the supervision of a Bakufu commissioner.

- The Yoshiwara district, originally located on the Nihonbashi, was moved like Kabuki to the edge of the city north of the Sensō-ji in front of the "Nihon Zutsumi" dike. This was planned before the Meireki fire and the "New Yoshiwara Quarter" was opened in 1658.

Hanami at the end of April has always been a pleasure . Famous for their cherry blossom was the Asuakayama in Ōji in the north and the Gotemba in the south off Shinagawa. Further out to the west, the area of Koganei on Tamagawa was known. Not only the people but also the nobility undertook excursions to the Hanami, provided with picnic suitcases.

Edo and its city maps

The urban development of Edo is well documented, as city maps were incessantly produced, either as general plans or as district maps ( Kiri-ezu ). The standard work shows more than 700 cards with all card types and all editions. In terms of content, they are pragmatically adapted to the rectangular shape and thus more or less distorted, but are topologically in order.

The overall plans show the main streets, bridges, the residences of the Tokugawa and the daimyo with their respective coats of arms and names; they also show the temples with their religious orientation and were therefore quite suitable for an initial orientation. Around 1800, Kiri-ezu district maps appeared in six-color printing , which, with their scale, were better suited to finding one's way. The cut-outs were chosen pragmatically and then distorted to a rectangular format. On these district maps, in addition to the main daimyō residences, the secondary residences and the Hatamoto residences are also entered. The chōnin, even the richest, remained nameless in the gray-shaded urban areas. A look at these colorful cards shows how mixed nobility, priests and citizens lived side by side in Edo.

From Edo to Tokyo

After the shogunate was dissolved in 1868, the new government renamed the city Tokyo ("eastern capital") and moved the seat of the Tenno in 1869 (he was 16 years old at the time) there. This relocation is not formally sealed either by law or by imperial decree. The city was badly damaged by the Kantō earthquake (1923) and almost completely destroyed in the Second World War (→ air raids on Tokyo ). When it was rebuilt twice, the city structure was changed by new streets, but if you look carefully you can still see the old Edo under today's Tokyo.

panorama

View from Atago Hill to the east. In the middle of the panorama you can see the Makino-Han (Echigo) secondary residence in the foreground.

See also

- Edo castle

- Edokko (residents of Edo)

- 100 famous views of Edo

Individual evidence

- ↑ 大 辞 林 第三版 at kotobank.jp. Retrieved January 26, 2013 (Japanese).

- ↑ These spellings reflect a weak i in the initial sound of the syllable e, which has now disappeared. Lutz Walter (Ed.): Japan seen through the eyes of the West . Prestel, Munich / New York 1994, p. 49.

- ↑ a b George Sansom: A History of Japan: 1615-1867 . Stanford University Press, Stanford 1963, p. 114.

- ↑ T. Ōhama, K. Yoshiwara: Edo Tōkyō nenpyō. Shogakukan, 1993, ISBN 4-09-387066-7 .

- ^ Andrew Gordon: A Modern History of Japan from Tokugawa Times to the Present. Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-19-511061-7 , p. 23.

- ↑ a b c d e f Kazuo Hanasaki (ed.): Ōedo. Monoshiri zukan. Shufu-no-Seikatsusha, 2000. ISBN 4-391-12386-X .

- ↑ a b Tokyoto rekishi kyoiku kenkyukai (ed.): Tokyoto no rekishi sanpo (jo) . Yamakawa shuppansha, 2001, ISBN 4-634-29130-4 , p. 122.

- ^ R. Iida, M. Tawara: Edo-zu no rekishi . Chikuchi shokan, 1988, ISBN 4-8067-5651-2 .

- ↑ Gotō Kazuo, Matsumoto Itsuya: Yomigaeru Bakumatsu. Asahi Shimbunsha, 1987, OCLC 475155769 , p. 8.

Remarks

- ↑ There is also the opinion that the two characters only reflect the sound value of this old field name. The name may come from the Ainu language . See entry "Edo" in the Konversationslexikon Kōjien ( 広 辞 苑 ).

- ↑ The best-known is perhaps the "Tora-no-mon" ("Tiger Gate"), which has only survived as the name of an intersection and subway station.

- ↑ Received is u. a. the Ōte-mon in this form.

- ↑ After the fire in 1657, the residences were rebuilt more modestly.

- ↑ The border was marked on maps as the "red line" ( 朱 引 き , shubiki). It mainly included outside temple areas, as their surroundings were used as hiding places.

- ↑ The Mitsukoshi ( 三越 ) department store is a direct successor. The name is made up of the first character of Mitsui and the first character of Echigoya, read here koshi.

- ↑ The woodcut ( 江 戸 の 三 幅 對 , Edo san fukutsui) shows: Kabuki - Ichikawa Danjūrō V. (1741–1806), Sumo - Tanikaze Kajinosuke II. (1750–1795) and Yoshiwara - Hana-ōgi des Ōgiya.

- ↑ In this area on the outskirts there was also a small quarter of the Eta , people who had "unclean" jobs such as the disposal of animal carcasses and tannery and who were therefore considered to be "in" outside of society.

- ↑ Many of these city maps are readily available as reprints.

Web links

- Left Edo screen ( Memento from September 4, 2012 in the Internet Archive )