Rangaku

As Rangaku ( Jap. 蘭学 , "Holland Customer", "Holland Studies") refers to the exploration of the West through the medium of the Dutch language during the period of so-called Sakoku from 1641 to 1854. Although was the access to Western books, instruments and other Materials initially hampered by various restrictions, but after 1720, when Shôgun Tokugawa Yoshimune completely released the import of foreign books - with the exception of Christian writings - not only the privileged interpreters, personal physicians and scholars were able to evaluate Dutch or books translated into Dutch . At the same time, information was collected from the Europeans in the Dejima trading post and objects brought into the country by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) were studied. Medicine , military technology and agricultural science were of particular interest . In addition, the Dutch had to provide annual reports on events in Europe and other significant events in the world ( fūsetsugaki ).

Thanks to these studies, Japan, despite its limited international relations, was not completely unprepared when in 1853 the so-called black ships under the command of the American Matthew Perry entered the Bay of Edo to force the country to open up. The colonial aspirations of the Western powers in Asia were clear, they knew about their technology and, in dealing with Western know-how, the foundations had been laid for the rapid modernization of the country in the second half of the 19th century.

terminology

The term “Rangaku” is not unencumbered. It was introduced and used by the doctor Sugita Gempaku ( 杉 田 玄 白 ; 1733-1817) and other pioneers of the 18th century. Especially Sugita's age memoirs ( Rangaku koto hajime , dt. "Beginning of Holland Studies") exerted a great influence on his contemporaries and historiography - all the more since this script was propagated by Fukuzawa Yukichi , one of the fathers of modern Japan. Sugita largely ignored the historical pioneering achievements of the interpreters / scholars in Nagasaki and set a monument to himself and his contemporaries as the founder of a new movement. In fact, however, Dutch studies in the late 18th and 19th centuries are based on the achievements of previous generations. Many a 17th century manuscript was used during this time, sometimes with ignorance of its age.

The term Yōgaku ( 洋 学 , dt. "Western Studies") can be found in the conceptual environment of Rangaku . It was initially used to denote the expansion of Japanese studies into other fields of science and technology and the breakaway from the Dutch language in the 19th century. In this sense he still appears occasionally today. During the last decades, the use as a general term for the Japanese preoccupation with the West before the Meiji period spread. This interpretation includes the age of Portuguese-Japanese contacts and is now supported by the majority of authors on the history of Western studies ( yōgakushi ). In Chinese, the term xixue ( 西学 , literally "Western studies") is used for this.

history

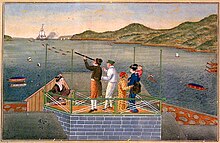

The merchants, trade assistants and doctors of the Dutch East India Company on the artificial island of Dejima in Nagasaki Bay were the only Europeans allowed to land in Nagasaki in 1640. Your stay was carefully monitored. In addition, the head ( opperhoofd ) of the branch ( factorij ) had to move to Edo once a year (from 1790 every four years) to pay his respects to the Shogun . The Japanese learned about the achievements of the industrial and scientific revolution of the West through the "redheads" ( kōmōjin ). After the study of the Dutch language and writing gained momentum outside of Nagasaki's interpreting circles in the 18th century, Japanese scholars acquired and translated western half-timbered works with increasing success. In addition, medical instruments, stills, magnifying glasses, microscopes, telescopes, “weather glasses”, clocks, oil paintings and many other useful or curious rarities have been arriving in the country since the 17th century, stimulating the interest in the West. Electrical phenomena and hot air balloons became known very early on.

In just over two hundred years, numerous books on the Dutch language, Western medicine and technology were printed, which enjoyed great popularity among the population. Thanks to the high level of education (the level of literacy was between 70 and 80 percent) in town and country, the information received about Dejima was disseminated to the regions. Japanese people thirsting for knowledge moved to Nagasaki to study Western texts and objects with nationally known "Holland interpreters" ( 阿蘭 陀 通 詞 / 阿蘭 陀 通事 , oranda tsūji ). Treasures were exhibited at “medicinal product meetings” ( yakuhin'e ) and like-minded people from other regions met. There was no end to the rush of visitors for famous collectors. In metropolitan areas there were also shops that specialized in Western curios. Eventually private schools specializing in Dutch studies ( 蘭 学 塾 , rangaku juku ) emerged.

Early explorations (1640-1720)

During the first phase of Rangaku , knowledge transfer took place selectively and with various restrictions. After the expulsion of the last Portuguese ( Nanbanjin ) in 1639 and the suppression of Japanese Christianity , Western and Chinese books with Christian content were strictly banned. Medical, astronomical and other scientific works continued to come into the country with the approval of the authorities. At the same time, influential people around the Shogun, partly out of personal interest, partly for political motives, requested all kinds of instruments, paintings, medicines, seeds, models and other rarities and had them explained to them in addition to specialist books. In this way, the Japanese translators at the Dejima branch, who then had to prepare a report, also got to know a lot of Western things, developed a new nomenclature and acquired considerable specialist knowledge. Some, such as Narabayashi Chinzan ( 楢 林 鎮 山 ; 1648–1711), Nishi Gempo (( 西 玄 甫 ;? -1684)) 、 Motoki Shōzaemon ( 本 木 庄 左衛 門 ; 1767–1822), Yoshio Kogyū (1724–1800) u. am passed their knowledge on to students. As the interpreting office remained in the family, a considerable treasure trove of writings, objects and knowledge was accumulated in these houses.

The Dutch also provided annual written reports on political events in the world. On the occasion of their court trip to Edo , they also had to give a variety of information in conversations with dignitaries, which was recorded and repeatedly checked. After the Leipzig surgeon Caspar Schamberger had impressed influential gentlemen with his therapies during his ten-month stay in Edo in 1650, the doctor was a sought-after discussion partner. At the same time, all sorts of useful and curious things came into the country through so-called private trade. Many of the notes written by the interpreters and doctors were copied by hand until the 19th century and distributed in all parts of the country. The first books on surgery for the "redheads" appeared as early as the 17th century, and later generations also repeatedly reverted to the early pioneering achievements.

Further dissemination of western knowledge (1720–1839)

Until the loosening of import restrictions for foreign books under the eighth Shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune in 1720, the acquisition of the Dutch language and the development of Western texts was the domain of the Japanese interpreters at the Dejima branch, but thanks to Yoshimune's support, Dutch skills were now also spreading among interested people Scholars in other regions.

Nagasaki remained the place where you could get to know people and objects from Asian and Western countries and where a wealth of information could be accumulated in a short time. The interpreters' collections and knowledge continued to be valued. The estate of the interpreter and doctor Yoshio Kōgyū alias Kōsaku with its 'Holland Hall' ( Oranda yashiki ) and foreign plants in the garden was known throughout the country. A study visit to Nagasaki ( 長崎 遊 学 , Nagasaki yūgaku ) can be found in the biography of almost all fans of Dutch studies. In Nagasaki, like-minded people from different regions got to know each other, which contributed to the expansion of horizons and the creation of a nationwide network.

Handwritten copying of records also played an important role in the dissemination of knowledge in the 18th century. But now more printed works appeared, dealing with the technology and science of the West. A well-known writing of this direction is the book "All kinds of conversations about the redheads" ( 紅毛 紅毛 話 , Kōmō zatsuwa ) published by Morishima Chūryō ( 森 嶋 中 良 ; 1754-1808) in 1787 , which introduces western achievements such as the microscope and the hot air balloon , medical Describes therapies, painting techniques, printing with copper plates, building large ships, electrical equipment and updating Japanese geography knowledge.

In the years 1798–1799 the thirteen volumes of the first Dutch-Japanese dictionary Haruma-wage ( 波 留 麻 和解 , "Japanese explanation of Halma") appeared, which was based on François Halma's "Woordenboek der Nederduitsche en Fransche taalen" and comprised 64035 headwords. The huge project was carried out by the doctor and scholar Inamura Sampaku (1758–1811) with the help of Udagawa Genzui ( 宇田 川 玄 隋 ; 1755–1797) and Okada Hosetsu ( 岡田 甫 説 ). All three were students of the doctor and Holland Kundler Ōtsuki Gentaku (1757-1827).

Between 1804 and 1829, the shogunate opened schools across the country through which the new ideas spread. The Europeans on Dejima were still monitored, but there were more contacts with Japanese scholars, even with interested Japanese rulers ( daimyō ) such as Matsura Kiyoshi, Shimazu Shigehide , Okudaira Masataka , Hotta Masayoshi , Nabeshima Naomasa and others. Particularly influential was the German doctor and researcher Philipp Franz von Siebold , who managed to use a property in the hamlet of Narutaki near Nagasaki, where he treated patients and trained Japanese students in Western medicine. In return, these students and many of his contact persons helped him to build up an extensive regional and natural history collection. In teaching western medicine, the young Siebold hardly got above the level of his predecessors. In Narutaki, however, his students had ample opportunity to observe the work and way of thinking of a European scholar in opening up new areas of knowledge. This turned out to be far more significant. Students like Ito Keisuke (1803-1901), Takano Chōei (1804-1850), Ninomiya Keisaku (1804-1862), Mima Junzō (1795-1825) or Taka Ryōsai (1799-1846) later played an important role in the intellectual opening of Japanese science.

Politicization (1839-1854)

With the increasingly heated debate about Japan's relationship to the West, Holland customer also gained political traits. Most scholars of Holland ( rangakusha ) advocated a greater absorption of Western knowledge and the liberalization of foreign trade in order to strengthen the country technologically and at the same time to preserve the Japanese spirit that was considered to be superior. But in 1839 people who dealt with Western knowledge were briefly suppressed when they criticized the edict issued by the Shogunate to expel foreign ships . This law was enacted in 1825 and ordered the eviction of all non-Dutch ships from Japanese waters. Among other things, it was the cause of the Morrison incident of 1837. The controversial regulation was repealed in 1842.

Thanks to Dutch studies, Japan had a rough picture of Western science. With the opening of the country towards the end of the Edo period (1853–1867), this movement embarked on broader, comprehensive modernization activities. After the liberalization of foreign trade in 1854, the country had the theoretical and technological foundations to promote radical and rapid modernization. Students were sent to Europe and America, and Western specialists were invited to Japan as “foreign contractors” ( o-yatoi gaikokujin ) to teach modern science and technology.

Important areas of the Dutch customer

medicine

As early as the 17th century, books on medicine came to the country through the Dutch that were explained to one another, and in the 18th century they could more and more develop and translate them on their own. For a long time, the focus was mainly on surgical therapies (treatment of wounds, tumors, fractures, dislocations, etc.). No special knowledge of Western pathology was required for this. Japanese texts on western anatomy can be found as early as the 17th century, but they played no role in medical practice. Up until the 19th century, not only doctors of the Dutch direction ( 蘭 方 医 , ranpō-i ) proceeded eclectically . The adoption of Western remedies and ideas can also be observed among followers of traditional medicine.

The turn to anatomy and the dissection of corpses was not initiated by a Dutch expert, but by a representative of the Sino-Japanese tradition, Yamawaki Tōyō ( 山 脇 東洋 ; 1706–1762), who had become aware of discrepancies in classical texts and the “nine organs -Concept ”of the Chinese Zhou-Li plant . The results of the one-day dissection carried out on an executed criminal with official approval were published in 1759 under the title Zōshi ( 蔵 志 , dt. "Anatomy"). From today's point of view, the content is poor, but this section and the possibility of an officially tolerated publication caused a great stir. There were sections in many parts of the country. Kawaguchi Shinnin ( 河口 信任 ; 1736–1811) was the first doctor who picked up a knife himself. He and his mentor Ogino Gengai ( 荻 野 元凱 ; 1737–1806), an eclectic traditionalist, relied more than Yamawaki on their own observation, measured organs and recorded their properties. Against Ogino's resistance, who feared confusion in the medical profession and unrest among the population, Kawaguchi published the work Kaishihen ( 解 屍 編 , German "corpse section") in 1774 .

In the same year the “New Treatise on Anatomy” ( 解体 新書 , Kaitaishinsho ), a translation of the “Ontleedkundige Tafelen” (1734), a Dutch edition made by Maeno Ryōtaku , Sugita Gempaku , Nakagawa Jun'an , Katsuragawa Hoshū and other doctors, was published the “Anatomical Tables” (1732) by Johann Adam Kulmus . The illustrations come from Odano Naotake (1749–1780), who was trained in Western painting . In terms of content, this work surpassed everything that had previously been published on anatomy. It stimulated a new view of the human body and at the same time served as an example of how to gain access to high-quality Western knowledge.

On October 13, 1804, the surgeon Hanaoka Seishū (1760–1835 ) performed the world's first general anesthesia for breast cancer surgery ( mastectomy ) . For this he used an anesthetic developed on the basis of Chinese herbs, which first led to insensitivity to pain and then to unconsciousness. This pioneering achievement took place more than forty years before the first Western attempts with diethyl ether (1846) and chloroform (1847) by Crawford Long , Horace Wells and William Morton .

In 1838 Ogata Kōan founded a school of Dutch studies in Osaka , which he called Tekitekisai-juku ( 適 々 斎 塾 , often shortened to Tekijuku ). The most famous students include Fukuzawa Yukichi , the military man and politician Ōtori Keisuke ( 大鳥 圭介 ; 1833–1911), the doctor Nagayo Sensai (1838–1902), the shogunate opponent Hashimoto Sanai ( 橋本 左 内 ; 1834–1859), the Reformer of the army Ōmura Masujirō ( 大村 益 次郎 ; 1824–1869), the politician Sano Netami ( 佐野 常 民 ; 1822 / 23–1902), who played a key role in the later modernization of Japan. Ogata was the author of Byōgakutsūron ( 病 学 通 論 ) published in 1849 , the first Japanese book on pathology .

physics

Some of the earliest Rangaku scholars were busy compiling theories of 17th century physics. Shizuki Tadao (1760–1806) from a family of interpreters in Nagasaki had the greatest influence . After being the first to complete a systematic analysis of Dutch grammar, in 1798 he translated the Dutch edition of "Introductio ad Veram Physicam" by the English author John Keil (1671–1721), which deals with the theories of Isaac Newton . Shizuki coined several basic scientific terms in the Japanese language that are still used today: 重力 ( jūryoku , gravity ), 引力 ( inryoku , tensile force ), 遠 心力 ( enshinryoku , centripetal force ) and 集 点 ( jūten , center of gravity ).

The Confucian scholar Hoashi Banri (1778-1852) published a manual of the physical sciences (title: 窮 理 通 , Kyūri-tsū ) on the basis of thirteen Dutch books in 1810 after he had taught himself the foreign language using a dictionary.

Electrical phenomena

Experiments with electricity were widespread from around 1770. After the invention of the Leiden bottle in 1745, Hiraga Gennai acquired similar types of electrifying machines from the Dutch around 1770. Static electricity was generated by the friction of a gold-coated stick on a glass tube. The Japanese recreated the Leyden bottles and developed them into erekiteru ( エ レ キ テ ル ) devices. As in Europe, these early generators were primarily used for amusement and were offered for sale in curio shops. But attempts were also made to use them in medicine. In the book “All sorts of conversations about the redheads” erekiteru is described as a machine “which allows sparks to be drawn from the human body in order to treat sick parts of the body.” In particular, the physically ambitious inventor Sakuma Shōzan developed further devices on this basis.

Japan's first treatise on electricity, "Principles of the Dutch invented elekiteru " ( 阿蘭 陀 始 制 エ レ キ テ ル 究理 原 ) was published in 1811 by Hashimoto Muneyoshi (1763-1836). Hashimoto describes experiments with electrical generators, the conduction of electrical energy through the human body and the experiments with lightning and numerous other electrical phenomena carried out by Benjamin Franklin around 1750 .

chemistry

In 1840 Udagawa Yōan (1798-1846) published his "Introduction to Chemistry" ( 舎 密 開 宗 , Seimikaisō ), which describes a wide range of scientific findings from the West. Most of the Dutch material he used probably goes back to the "Elements of Experimental Chemistry" published by William Henry in 1799 . Utagawa also wrote a detailed description of the battery invented forty years earlier by Alessandro Volta . In 1831 he rebuilt it and used it in various experiments. He also tried his hand at medicine because, like doctors in Europe, he believed in the therapeutic powers of electricity.

Utagawa's book also introduces the discoveries and theories of Antoine Laurent de Lavoisier for the first time . Some of the translations he created have found their place in modern scientific terminology in Japan: 酸化 ( sanka , oxidation ), 還 元 ( kangen , reduction ), 飽和 ( hōwa , saturation ) or 元素 ( genso , substance ).

optics

Japan's first telescope was a gift from the English captain John Saris to the shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1614 when he was trying to establish trade relations between England and Japan. The first refractor came into Japanese hands only six years after its invention by the Dutchman Hans Lipperhey .

These lens telescopes had been supplied to Japan in considerable numbers by the Dutch East India Company since the 1940s: for example 1640 (4 pieces), 1642 (2 pieces), 1644 (2 pieces), 1645 (20 pieces), 1646 ( 10 pieces), 1647 (10 pieces), 1648 (7 pieces), 1654 (41 pieces), 1658 (3 pieces), 1660 (28 pieces), 1671 (23 pieces), 1676 (19 pieces). Inoue Masashige (1585–1661), who was particularly interested in Western science and technology, knew about Galileo Galileo's observations during those years. In 1647 he ordered "a particularly beautiful long telescope with which one can discover the four satellites of Jupiter, which are otherwise hidden from our eyes, next to other small stars". At the beginning of the 18th century, there were craftsmen in Nagasaki who were able to prepare the telescopes supplied for local use and also to build them.

After the gunsmith and inventor Kunitomo Ikkansai (1778-1840) had spent several months in Edo in 1831 to get to know Dutch objects, he built a Gregory telescope (reflector) in Nagahama (on Lake Biwa ), a European invention the year 1670. Kunitomo's reflector telescope had a magnification of 60 times , which allowed him to make detailed observations of sunspots and the topography of the moon. Four of his telescopes have been preserved.

Light microscopes were invented in Europe in the late 16th century, but it is unclear when they were first used in Japan. For the 17th century, only magnifying glasses can be verified , which were ordered and delivered in considerable numbers. Some Europeans, e.g. For example, the doctor Engelbert Kaempfer carried single-lens microscopes ( Microscopium simplex or Kircher's "Smicroscopium") with them. It is therefore possible that orders from luijsglaesen (louse glasses) are such microscopes. Detailed descriptions of two-lens microscopes can be found in the “Night stories from Nagasaki” ( 長崎 夜話 草 , Nagasaki yawagusa ) printed in 1720 and later in “All sorts of conversations about the redheads” (1787). Just like telescopes, microscopes were also copied with great skill by local craftsmen. Microscopes about ten centimeters high ( 微塵 鏡 , mijinkyō ) were popular souvenirs from Kyoto. As in Europe, the microscopes were used partly for scientific observation and partly for amusement.

The magic lantern was first scientifically described by Athanasius Kircher in 1671 and enjoyed great popularity in Japan from the 18th century. The mechanism of a magic lantern, called "silhouette glass " ( 影 絵 眼鏡 ) in Japan , was explained in the book Tengutsu ( 天狗 通 ) in 1779 using technical drawings.

Lenses for pinhole cameras ( camera obscura ), which project the outside world onto the wall opposite the lens, were delivered to Japan as early as 1645 ( doncker camer glasen ). However, nothing is known about their use.

The first magnifying mirror ( vergrootende mirror ) for Japan appear in the delivery papers of the Dutch East India Company in the year 1637th

technology

Machines and clocks

Karakuri ningyō are mechanical dolls or automatons from the 18th and 19th centuries. The word karakuri (絡 繰 り) means "mechanical device", ningyo stands for "doll". Most of these dolls were for pleasure, their skills ranged from shooting arrows to serving tea. These mechanical toys were forerunners to the machines of the Industrial Revolution and were powered by spring mechanisms.

Lantern clocks made of brass or iron with a spindle escapement came into the country in the 16th century via the Jesuit missionaries and since the 17th century via the Dutch East India Company. Local craftsmen soon developed the first Japanese clocks (wadokei; German "Japanese timepieces"). Since the length of the six time units of the day in summer differed from that in winter, they had to develop a clockwork that could do justice to this difference. The complex Japanese technology reached its climax in 1850 in the 10,000-year-old clock ( mannen-tokei ) of the gifted inventor Tanaka Hisashige , who later founded the Toshiba group.

pump

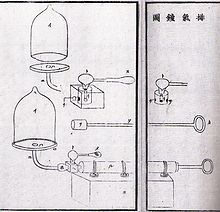

After the experiments of Robert Boyle , air pumps spread throughout Europe from around 1660. In Japan the first description of a vacuum pump appeared in 1825 in "Observation of the Atmosphere" ( 気 海 観 瀾 ) by Aoji Rinso . Nine years later, Utagawa Genshin described both pressure pumps and vacuum pumps in "Admirable Things from the Far West" ( 遠 西医 方 名 物 考 補遺 ).

There were also developed a number of practical equipment, such as air guns of Kunitomo Ikkansai . He had repaired the mechanism of some air rifles that the Dutch had given the Shogun. Based on the mechanics of the air rifle, he also developed a constantly burning oil lamp in which the oil was ignited by continuously pumping compressed air. In agriculture, Kunitomo's invention was used for large irrigation pumps.

Aviation experiments

With a delay of less than four years, the Dutch reported the first flight of a hot air balloon by the Montgolfier brothers in Dejima in 1783 . This event was described in 1787 in "All sorts of conversations about the redheads".

In 1805, barely twenty years later, the German scientists Johann Caspar Horner and Georg Heinrich von Langsdorff (both members of the Krusenstern expedition) built a hot air balloon out of Japanese paper and demonstrated the new technology in the presence of 30 Japanese delegates. Hot air balloons were used for experimental purposes or entertainment until the development of military balloons during the early Meiji period .

Steam engines

Knowledge of the steam engine spread to Japan in the first half of the 19th century. The first machine of this type was not designed by Hisashige Tanaka until 1853 after he had attended a demonstration by Evfimi Putyatin in the Russian embassy .

The oral remarks of the Rangaku scholar Kawamoto Kōmin recorded by Tanaka Tsunanori in 1845 under the title "Surprising Machines of the West" ( 遠 西奇 器 述 , Ensei kikijutsu ) were published in 1854. At that time it had become generally clear that Western knowledge had to be disseminated more quickly after the country was forced to open up. The book contains detailed descriptions of steam engines and steam ships.

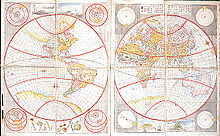

geography

Modern cartographic knowledge of the world was imparted to the Japanese during the 17th century through maps and globes brought into the country by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) - in many cases on the basis of orders from high-ranking personalities. The Chinese map of the world ( 坤 輿 万 国 全 図 ), which the Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci published in Beijing in 1602 , also had a great influence .

Thanks to this information, the knowledge of Japan was roughly equivalent to that of the European countries. On this basis, Shibukawa Harumi made the first Japanese globe in 1690 .

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the land was measured and topographically mapped using Western techniques. Particularly famous are the maps created by Inō Tadataka at the beginning of the 19th century, which, with their accuracy of up to 1/1000 degrees, were still of great use in the Meiji period.

biology

The description of nature made great strides, largely influenced by the work of the encyclopedists and by Philipp Franz von Siebold , a German doctor who served the Dutch on Dejima. Ito Keisuke wrote numerous books with descriptions of animal species on the Japanese islands, with drawings of almost photographic quality. Also of great interest pushed the entomology after the use had enforced by microscopes.

Occasionally there was also a Western takeover of Japanese research, for example in the case of silkworm breeding. Von Siebold brought the “Secret Treatise on the Silkworms” ( 養蚕 秘録 , Yosan hiroku ), published by Uegaki Morikuni in 1802 , to Europe, where it was translated into French by the Japanese scientist J. Hoffmann ( Yo-san-fi-rok - l'art d ' elever les vers a soie au Japon , 1848) and was later translated into Italian. While Japan had to import large amounts of raw silk and silk fabrics in the 17th century, it developed into the world's largest silk exporter at times in the 19th century.

Numerous plants have been imported from Asia since ancient times. American plants such as tobacco and potatoes then also came into the country via the Portuguese. The deliveries of seeds and saplings continued even in the age of the Japanese-Dutch exchange. Among other things, white cabbage and tomatoes were introduced .

However, Japanese agriculture and horticulture had reached a level that could not be exceeded in Europe either. The wealth of Japanese ornamental plant breeding has already been described by travelers such as Andreas Cleyer, Georg Meister and Engelbert Kaempfer. Especially after the opening of the country, western plant hunters rushed to Japan and brought all kinds of plants to Europe and America ( ginkgo , hydrangeas , magnolias , Japanese maples, biwa, kaki , kinkan, camellia, bush peonies, virgin vines, wisteria, etc.).

Aftermath

Replica of the "black ships"

When Commodore Matthew Perry , the Convention of Kanagawa negotiated, he delivered the Japanese negotiators also numerous technical gifts. Among them were a small telegraph, and a small steam engine , together with rails. These gifts were also immediately examined more closely.

The Bakufu, who saw the arrival of Western ships as a threat and a factor of destabilization, ordered the construction of warships according to Western methods. These ships, including the Hōō Maru , the Shōhei Maru and the Asahi Maru , were built within two years according to the descriptions in Dutch books. Research also took place in the field of steam engines. Hisashige Tanaka , who created the "10,000 Years Clock", built the first Japanese steam engine based on the technical drawings from the Netherlands and on observations of a Russian steamship that was anchored in Nagasaki in 1853. The first Japanese steamship, the Unkōmaru ( 雲 行 丸 ) , was built in the Satsuma fief in 1855 . The Dutch naval officer Willem Huyssen van Kattendijke commented in 1858:

- "There are a few imperfections in the details, but I take my hat off to the ingenuity of the people who could build ships like this without seeing the machine and relying only on simple drawings."

Last phase of the "Holland customer"

After the forced opening of Japan by Commodore Perry, the Dutch continued to play a key role in the transfer of Western knowledge for several years. Japan relied heavily on their know-how to introduce modern shipbuilding methods. The Nagasaki Naval Training Center ( 長崎 海軍 伝 習 所 ) was established in 1855 on the instructions of the Shogun to enable smooth cooperation with the Dutch. Dutch naval officers taught here from 1855 to 1859 until the center was relocated to Tsukiji in Tokyo , where British teachers dominated.

The center's equipment included the Kankō Maru steamship , which was handed over to Japan by the Dutch government in 1855. Some gifted students in the training center, including the future Admiral Enomoto Takeaki , were sent to the Netherlands for five years (1862–1867) to deepen their knowledge of the art of sea warfare.

Persistent influence of the Dutch customer

Numerous Dutch scholars played a key role in the modernization of Japan. Scientists such as Fukuzawa Yukichi , Otori Keisuke , Yoshida Shōin , Katsu Kaishu and Sakamoto Ryōma expanded the knowledge they had acquired during the isolation of Japan and made it the language of research towards the end of the Edo period and in the following decades English and German (medicine, law, forestry, etc.) replaced Dutch.

These scholars advocated a move towards western science and technology in the final stages of Tokugawa rule. In doing so, however, they encountered resistance from isolationist groups such as the Samurai militia Shinsengumi (German: "New Chosen Association") fighting for the preservation of the shogunate . Some were murdered, such as Sakuma Shozan in 1864 and Sakamoto Ryōma three years later.

swell

- ↑ Contrary to popular belief, there was no general ban on importing books. On October 31, 1641, a communication to the East India Company expressly excluded works on medicine, astronomy and nautical science. The company's trading papers since 1651 also show numerous book orders by high-ranking personalities. Michel (2010)

- ↑ Further information on the people at Kotobank (Japan.)

- ↑ When the Dutch East India Company was informed of the conditions of use for the Dejima branch in 1641, the question of books also arose, to which the office diary of the head of the factories recorded the following message from Reich inspector Inoue Masashige: “Oock dat egeene printed books different from van de medicijnen, chirurgie end pilotagie tracterende, sea in Japan en able te brengen end dat sulcx all aen sijn Edht (om Battavia comende) delivered te adverteren, ”. See Michel (2011), p. 78f.

- ↑ Morishima was also known as Shinrabanshō / Shinramanzō ( 森蘭 万象 )

- ↑ Utopian surgery - Early arguments against anesthesia in surgery, dentistry and childbirth

- ↑ The name goes back to an author name Tekitekisai used by him.

- ↑ Shizuki Tadao also wrote the first translation of Engelbert Kaempfer's treatise on Japanese graduation policy, for which he coined the term sakoku ( 鎖 国 , "state graduation ") in 1801 . For the history of the reception of this new term, see Ōshima (2009).

- ↑ Yoshida Tadashi: Hoashi Banri. In: Michel / Torii / Kawashima (2009), pp. 128-132

- ↑ a b c d More in Michel (2004).

- ↑ The name mijin comes from Buddhism and describes the smallest particles of matter, similar to the Greek átomos

- ↑ literally something like "move intricately"

literature

- Sugita Gempaku: Rangaku kotohajime ( Eng . "The beginnings of the Holland customer"). Translated by Kōichi Mori. Sophia University, Tokyo 1942.

- Numata Jirō: Western learning. a short history of the study of western science in early modern Japan . Translated by RCJ Bachofner, Japan-Netherlands Institute, Tokyo 1992.

- Carmen Blacker: The Japanese Enlightment. A study of the writings of Fukuzawa Yukichi . Cambridge 1964.

- Marius B. Jansen: Rangaku and Westernization. In: Modern Asian Studies . Cambridge Univ. Press, Vol. 18, Oct. 1984, pp. 541-553.

- Kazuyoshi Suzuki ( 鈴木 一 義 ): Mite tanoshimu Edo no tekunorojii ( 見 て 楽 し む 江 戸 の テ ク ノ ロ ジ ー , roughly equivalent to “Entertaining considerations of edo-age technology”. Sūken Shuppan, Tokyo 2006 ( ISBN 4-410-13886-3 )

- Timon Screech: Edo no shisō-kūkan ( 江 戸 の 思想 空間 , dt. "The intellectual world of Edo"). Seidosha, Tokyo 1998 ( ISBN 4-7917-5690-8 )

- Wolfgang Michel: Departure into “inner landscapes”. On the reception of western body concepts in medicine of the Edo period . MINIKOMI, No. 62 (Vienna, 2001/4), pp. 13–24. ( PDF file, Kyushu University Repository )

- Wolfgang Michel: Japanese imports of optical instruments in the early Edo period . In: Yōgaku - Annals of the History of Western Learning in Japan , Vol. 12 (2004), pp. 119-164 (in Japanese). ( PDF file, Kyushu University Repository )

- Wolfgang Michel, Torii Yumiko, Kawashima Mabito: Kyûshû no rangaku - ekkyô to kôryû ( ヴ ォ ル フ ガ ン グ ・ ミ ヒ ェ ル ・ 鳥 井 裕美子 ・ 川 嶌 眞 人 共 編 『九州 の』 蘭 と学 ー 越境 Crossing the border - customer crossing in Kyush and と学 ー 越境 . Shibunkaku Shuppan, Kyôto, 2009. ( ISBN 978-4-7842-1410-5 )

- Wolfgang Michel: Medicine, remedies and herbalism in the Euro-Japanese cultural exchange of the 17th century. In: Hōrin - Comparative Studies on Japanese Culture, No. 16, 2010, pp. 19-34.

- Wolfgang Michel: Glimpses of medicine in early Japanese-German intercourse. In: International Medical Society of Japan (ed.): The Dawn of Modern Japanese Medicine and Pharmaceuticals -The 150th Anniversary Edition of Japan-German Exchange. Tokyo: International Medical Society of Japan (IMSJ), 2011, pp. 72-94. ( ISBN 978-4-9903313-1-3 )

- Akihide Ōshima: Sakoku to iu gensetsu (“ State Degree ” as Discours). Minerva Shobō, Kyoto 2009 ( 大 島 明 秀 『鎖 国 と い う 言 説 - ケ ン ペ ル 著 ・ 志 筑 忠雄 訳『 鎖 国 国 論 』の 受 容 史』 ミ ネ ル ヴ ァ 書房 、 2009 年 )