Engelbert Kaempfer

Engelbert Kaempfer (born September 16, 1651 in Lemgo , † November 2, 1716 in Lieme ) was a German doctor and explorer . Its official botanical author's abbreviation is “ Kaempf. "

In the course of an almost ten-year research trip (1683 to 1693), which took him via Russia and Persia to India , Java , Siam and finally Japan , he gathered a wealth of knowledge on geography, nature, society, religion, politics, administration as well as the sciences and arts of the regions visited. His writings are considered to be important contributions to early modern exploration of the countries of Asia. They also shaped the European image of Japan in the 18th century and served as a reference work for many explorers until the early 19th century.

Life

Engelbert Kaempfer was the second son of Johannes Kemper , pastor at the St. Nicolai Church in Lemgo, and his wife Christina Drepper, the daughter of his predecessor. After the early death of his first wife around 1654, his father married Adelheid Pöppelmann. From 1665 Engelbert first attended the Lemgoer Gymnasium and from 1667 the Latin school in Hameln. At the time, it was common for gifted students to change schools several times in order to broaden their perspective and improve their professional opportunities. Another reason was possibly that in the years 1666 and 1667 his two uncles Bernard Grabbe and Andreas Koch were executed during the Lemgo witch trials . From 1668 to 1673 he attended high schools in Lüneburg and Lübeck as well as the “Athenaeum” in Danzig , where he studied philosophy, history and old and new languages. There he published his first work under the title "De Maiestatis divisione" (On the division of the supreme power). This was followed by a long-term study of philosophy and medicine at the "high schools" in Thorn , Krakow and Königsberg . In 1681 he moved to the Academy in Uppsala .

In the Safavid Empire (1683 to 1685)

At the Swedish court Kaempfer made the acquaintance of Samuel von Pufendorf , who gave him to the Swedish King Karl XI. recommended as a doctor and legation secretary for an embassy under the direction of the Dutch Ludwig Fabritius (1648–1729) to the Russian and Persian courts. During this trip he trained his observation skills and made extensive records of the country and people in the regions visited. The delegation set out from Stockholm on March 20, 1683 and traveled via Finland , Livonia and Moscow to Astrakhan , where they arrived on November 7, 1683 and from where they continued their journey across the Caspian Sea by ship . On 17 December it reached Shemakha , capital of the then still under Iranian standing rule region Shirvan . Kaempfer used the one-month stay there to visit the Fontes Naphta oil wells in Badkubeh (now Baku ), which he was the first European to explore and describe in more detail. Exhibition boards in the Baku Museum still commemorate Kaempfer's visit. On January 14, 1684, the embassy arrived in Rasht in northern Iran and traveled from there via Qazvin , Qom and Kashan to the Safavid capital Isfahan , where they arrived on March 29, 1684, one year after their departure from Stockholm.

Kaempfer stayed in Isfahan for a total of 20 months and thus became one of the most important European witnesses to whom we owe valuable reports about the Iranian capital at that time, the administration of the Safavid state and life at court. Not least by learning Persian and Turkish, he was able to gain deep insights into life in 17th century Iran.

To East Asia

During his stay, Kaempfer learned of the presence of a Dutch trading post in Bandar Abbas and he decided to part with the unsuccessful Swedish embassy and seek a job with the Dutch East India Company (VOC). However, he had to wait a year and a half before he could finally leave for Bandar Abbas. On the way south he visited the ruins of Persepolis and studied the tablets with characters, for which he invented the name cuneiform . He lived for two and a half years in the climatically extremely stressful Bandar Abbas. Here, among other things, his work on the date palm was created . After lengthy trials and many letters of petition, he finally got a job. From 1685 to 1688 Kaempfer was a trading doctor in Bandar Abbas.

On June 30, 1688, he went as a ship's doctor on board the yacht Copelle , which had loaded Persian goods for Ceylon and Batavia . He reached Muscat , the capital of Oman , on July 16, 1688 . Although he only stayed a few days, he kept extensive records of Oman. His notes are now among the most important sources from that time, as he was one of the few European visitors to the country at the time. For around a year he worked as a ship's doctor in the Indian region, which at the time was part of the sphere of influence of the Dutch East India Company.

After arriving in Batavia , the company's administrative headquarters in East Asia, he applied unsuccessfully for a job at the local hospital. Here he met Parvé, the Chancellor of the Exchequer of the Dutch East India Company, with whom he became friends. In dealing with former travelers to Japan and educated people in Batavia, the plan for extensive exploration of the country then matured, which since 1639 had only very limited dealings with the outside world. In preparation he received all kinds of materials as well as a list of books etc. written in Dutch and Chinese that he was supposed to collect in Japan.

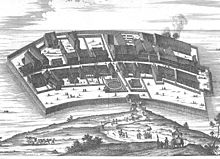

On May 7, 1690 Kaempfer left Batavia on board the Waelstrohm . The first stop was the Dutch settlement in Ayutthaya , where he visited the King of Siam . After a three-week stay, the Waelstrohm set sail again on June 7, 1690 and reached Nagasaki Bay on September 24, 1690 after violent typhoons . The company's headquarters were on the artificially raised island of Dejima (Deshima) in the immediate vicinity of the city. Nagasaki was the only permitted port of call for the East India Company (VOC) because of the so-called closure policy . All Europeans working on Dejima have been registered. Officially, they were considered Dutch. Kaempfer worked here as a ward doctor from 1690 to 1692. Although the Europeans were only allowed to leave the trading post on one or two day trips a year, thanks to the cooperation of Japanese partners such as his young caretaker Imamura Eisei , the interpreters Namura Gonpachi, Narabayashi Chinzan (1648 –1711) and others to collect and evaluate numerous objects, books and information.

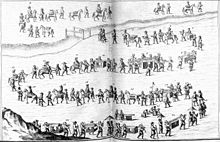

As a doctor, Kaempfer was also allowed to take part in the annual court trip of the Dutch representative (ndl. Opperhoofd ), who had to thank the Shogun in the castle in Edo (today Tokyo) for allowing him to trade with Japan. After crossing the island of Kyushu on the so-called Nagasaki Strait ( Nagasakikaidō ) one sailed on a small ship from Shimonoseki to Osaka and then moved by land over the famous East Sea Strait ( Tōkaidō ) to Edo. These two trips made it possible for him to check the information he had gathered so far, to expand it and to get to know important regions of the country first hand. Fortunately for him, botanizing was allowed, so that he was able to assemble an impressive collection of plant samples and at the same time use this pretext to make route maps. On the way he became aware of the Japanese giant crab , which got its name in modern nomenclature: Macrocheira kaempferi . Both a male and a female specimen can be seen today in his hometown, the old Hanseatic town of Lemgo in Lippe , in the Museum Hexenbürgermeisterhaus .

The reigning shogun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi in Kaempfer's time had a strong interest in the Europeans and, after the official reverence of the Dutch representative, had a kind of audience arranged in another hall of the palace, where all sorts of questions and answers came through the interpreters and Kaempfer among others was coerced into singing and dancing. Although Kaempfer found this "pickled herring dance" to be unreasonable, he still recorded it in detail in his manuscript "Today's Japan".

Return to Europe

On October 6, 1693, Kaempfer reached Amsterdam with the Pampus after a stopover in South Africa . After completing his doctorate at the Reich University in Leiden , where he gave ten medical observations, he returned to Lemgo in August 1694 and moved into the Steinhof in Lieme , which his father had acquired in 1675. Here he began to evaluate his treasures, but the medical practice and especially his duties as personal physician of the discerning Count Friedrich Adolf zur Lippe in Detmold proved to be time and energy consuming. Her unhappy marriage with Sophie Wilstach , who was more than 30 years his junior, in 1700 contributed to the growing exhaustion. In a letter to his Dutch friend Parvé in 1705 he wrote: I lead a restless and extremely arduous life between fields and courtiers.

In 1712 he finally succeeded in publishing the "Amoenitates Exoticae" with Meyer in his native Lemgo. However, a second manuscript, “Today's Japan” was never printed. Engelbert Kaempfer died on November 2, 1716 in the Steinhof at the age of 65. He was buried on November 15, 1716 in the Nicolaikirche in Lemgo. In his will he had decreed that his wife should go away empty-handed, and that his nephew Dr. Johann Hermann Kemper, son of his older brother Joachim, who worked as a syndic in Goslar .

The Heritage

According to Kaempfer's own words, he has not brought anything into his work that has been created from my own imagination, nothing that tastes like the office or smells of the study lamp. I limit myself to writing only what is either new or not thoroughly and completely handed down by others. As an explorer, I had no other aim than to collect observations of things that are nowhere or not sufficiently known to us. (Preface to Amoenitates Exoticae ) The 900-page work is aimed at the European scholarly world and consists of five books: the greater part is dedicated to Persia, the rest relates to Japan.

Kaempfer's Japanese factory

Large parts of the estate were bought in 1723 and 1725 by the personal physician of the English king and passionate collector Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753). He had the unprinted Japanese manuscript edited and translated by the young Swiss doctor and scholar Johann Caspar Scheuchzer and published in 1727 under the title The History of Japan . The systematic work filled a gap because a comprehensive, more recent description had not been available for decades. In addition, Kaempfer succeeded in largely freeing himself from the form of the travel description and spreading his observations in the form of topoi (geography, history, religion, etc.). The first editions of a French and a Dutch translation appeared as early as 1729. After the discovery of a second manuscript in the estate of Kaempfer's niece, the Enlightenment, later State Councilor and archivist Christian Wilhelm Dohm published a German version, which was also published by Meyer from 1777 to 1779 under the title Engelbert Kaempfer's History and Description of Japan . According to his own words, he had only made cautious textual changes , but actually translated entire chapters from The History of Japan that were missing in his manuscript . With one exception, he also adopted the illustrations of the English version selected and edited by Scheuchzer.

In the first half of the 20th century. once the impression arose that posterity had forgotten Kaempfer, but as Peter K. Kapitza shows in extensive studies, his work, especially the French edition, had a strong influence on the European intelligentsia of the Enlightenment . Thanks to the systematic conception and the wealth of information, it was used by future travelers to Japan as well as by European writers, encyclopedists and naturalists.

Kaemper's treatise on the Japanese “closing policy”, which was first published in the Amoemitates Exoticae and widely distributed in the appendix to the History of Japan and the following editions, caused a sensation . His image of a frugal, hardworking and harmoniously cohabiting society under the strict rule of the emperor ( Shogun ), which withdrew from the world for their protection, shaped the European image of Japan well beyond the 18th century. When translating the Dutch version of this treatise, the Japanese interpreter Shizuki Tadao coined the new term sakoku (national qualification), which became a key term in Japanese historiography of the 20th century, due to the complexity of the long Kaempfer's title . should be.

Botanical research

Kaempfer's botanical observations went well beyond those of his predecessors Andreas Cleyer and George Meister . Soon after his arrival, he started collecting plants and information. In addition to his caretaker Imamura, as his notes show, Narabayashi Chinzan and Bada Ichirōbei were particularly helpful here. The Japanese authorities actually tried their best to prevent exploration of the land and people, but as Kaempfer himself wrote, there were no problems with botanizing. In his records we find a number of leaves with records of plants. He got their names partly from his sources, partly they come from the picture dictionary Kinmōzui , which he had explained by Imamura and others. Kaempfer's herbarium was sold to Hans Sloane in London along with the Japan-related materials . During his lifetime, however, he was able to publish descriptions of a considerable number of plants as the 5th part of the Amoenitates Exoticae under the title Flora Japonica . He also added pictures to some. According to George Meister's descriptions in the Oriental-Indian Art and Pleasure Gardener (1692), this was the first scientific publication on the flora of Japan.

In the Flora Japonica we find, among other things, the first detailed western description of the ginkgo , a tree that has long been considered extinct. This was introduced in Japan around 1200 years ago. It still stands today in the area of temples and shrines and is also used to mark property boundaries in the country because of its straight, slim growth. When transliterating the Japanese name ginkyō , Kaempfer made a mistake that was immortalized by Carl von Linné's nomenclature as "Ginkgo". Kaempfer also paid great attention to the camphor tree . The orientalist Herbert de Jager , who gave Kaempfer detailed instructions before he left Batavia, had specifically asked him for plant samples and pictures of this tree. Huge old camphor trees can still be seen in many temples and shrines today. In Kaempfer's time, camphor trees were also cultivated for the production of camphor and camphor oil. Especially in the province of Satsuma (today Kagoshima prefecture ), large quantities of camphor were produced, which the East India Company bought in the 17th century.

Language research

As a result of his short stay, Kaempfer's research on the Japanese language remained far below the level of the grammars and dictionaries published by the Jesuits of the 16th and early 17th centuries. With the expulsion of the Portuguese and Spaniards, research into Japanese collapsed, and apart from a few twisted idioms there were no more observations on the country's language. Kaempfer wrote down an abundance of local names. He did pioneering work with regard to the plant names , which he added to his Flora Japonica along with the Chinese characters taken from the Kinmōzui . His transliterations are of value to language historians. The words and expressions he wrote down in Latin letters as an auditory impression reflect a number of peculiarities of the pronunciation of the time better than the morphologically sound transcription systems of the missionaries.

medicine

Hermann Buschoff introduced the Japanese term moxa in 1674 with a booklet on foot gout . The doctor Willem ten Rhijne coined the term acupuncture after his return from Japan . However, neither achieved a deeper understanding of the physiology and etiology behind these therapies. Kaempfer tried to go beyond their representations, which he succeeded to a certain extent with the description of concrete therapy cases. With regard to the interpretation of the mechanisms of action, however, it largely remained with the terminology and interpretation of its predecessors. In the 17th century, the technical and language skills of Japanese interpreters were not yet sufficient to explain theoretical aspects of medicine. In this way, the Qi of Chinese medicine was (almost inevitably) transformed into winds and vapors ("flatus et vapores"), which build up and cause imbalances in the organism. Kaempfer interpreted the mechanism of action of acupuncture and moxibustion as "revulsive" (revolutionary) :

- “According to European judgment, the place closest to the diseased part would be best suited to lure the fumes (and that is the point of burning). However, they ( the Japanese doctors ) often choose distant points which, according to anatomical principles, are only connected to the diseased region by the general body covering ... The scapula ( shoulder blade ) is successfully burned to heal and around the stomach To stimulate the appetite, the spine for pleural problems , the adductors of the thumb for toothache on the same side. Which anatomist can show a vascular connection here? "

His general interpretation of the choice of points for moxibustion (and acupuncture) had no influence on the early acupuncture practice in France (1810–1826), which was limited to needling pain points, instead of - as was common in China and Japan - with one To treat combination of near and far points.

It is different with Kaempfer's description of the treatment of "colic" with acupuncture among the Japanese. It is illustrated (p. 583) by the picture of a woman with 9 points painted in her upper abdomen. Behind this description stands the Japanese suffering Senki , a disruption of the flow of Qi in the abdomen. The therapy he observes follows a Japanese concept that ignores the Chinese meridians and regards the abdomen as the place of diagnosis and therapy.

Since the 15th century, the terms “colic” and “rising of the womb” have been used synonymously in Northern Europe, and since the beginning of the 19th century at the latest, the term “ hysteria ” has been added.

The French doctor Louis Berlioz (1776–1848), father of the composer Hector Berlioz , was the first in Europe to practice acupuncture. The first patient, a 24-year-old whom he treated with acupuncture in 1810, suffered from a "nervous fever" (= paraphrase of "hysteria"). He stabbed the points in the upper abdomen described by Kaempfer without combining them with distant points.

Engelbert Kaempfer dealt with tropical diseases and described the maggot foot (actinomycetoma) and elephantiasis .

reception

Kaempfer's writings were a milestone in the exploration of Japan. Much of the information from his geographical descriptions of Japan was included in the famous Encyclopédie by Diderot and d'Alembert under the respective keyword .

With regard to the assessment of the native religions, Kaempfer remained far more cautious than the Catholic missionaries to Japan of the 16th and early 17th centuries. While Christianity was forbidden and subjected to intense persecution in Kaempfer's time, Shinto , Buddhism and Confucianism coexisted without the antagonisms that shaped interdenominational relationships in the West. Among the representation of the religions of Japan, which is divided into several chapters, Kaemmer's description of the mountain ascetics (Japanese: Yamabushi ) deserves special attention as the first lengthy Western work on the Shugendo religion . Unfortunately, Kaempfer took some of his observations on magical practices, which can be found in the estate, as well as the drawing of a mudra (Japanese in ), i. H. a symbolic, actually secret, hand gesture that the interpreter Narabayashi Chinzan showed him in his book.

With regard to acupuncture and moxibustion, he provided the first concrete therapy and text examples that were received up to the 19th century. With the tapping needle and the guide tube he introduced, without realizing it, Japanese innovations of the 17th century that did not exist in China.

Kaempfer's Flora Japonica inspired the Swedish doctor and naturalist Carl Peter Thunberg to rework the Japanese flora on the basis of the taxonomy of his teacher Carl von Linné. Thunberg's work was then further developed in the 19th century by Philipp Franz von Siebold and Joseph Gerhard Zuccarini .

The emotionally charged description of his “audience” at the court of the shogun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi , adorned with an illustration , was particularly stimulating for European poets. The 'dance in front of the Japanese emperor' established itself in the image of Japan. Although the "pickled herring dance" ended with the death of Tsunayoshi in 1709, Philipp Franz von Siebold , who set out for Edo in 1826, still believed that he had to give similar performances in the Shogun's castle.

Last but not least, Kaempfer's writings served later generations in preparation for their trip to Japan and the authors as a historical reference point. Siebold, who researched Japan for more than a century after Kaempfer, feels obliged in many passages of his influential Nippon to correct, confirm, or expand Kaempfer's descriptions.

Research history on Kaempfer's life and work

Since the estate of Hans Sloane was included in the collection of the British Museum as the founding collection after his death , this part of the Kaempfers holdings was largely saved for posterity. Kaempfer's extensive family library of around 3,500 titles, however, was dispersed in an auction held in 1773. His “family record” and files from his divorce proceedings are in Detmold.

With the opening up and rapid modernization of Japan since the middle of the 19th century. interest in Kaempfer waned. It was not rediscovered until the 20th century, in which Karl Meier-Lemgo in particular made great contributions. The title of his first publication "Engelbert Kaempfer, a great stranger" reflects the situation at the time. In the beginning there was the cataloging of the printed works, after a trip to London the interest in the handwritten notes increased. Among Meier-Lemgo's numerous works, the translation of parts of the Amoenitates Exoticae ("Engelbert Kaempfer: 1651–1716. Strange Asia", 1933) and "Die Reiseagebücher Engelbert Kaempfers" (1968) should be emphasized. The translation of the first book of Amoenitates Exoticae , which the Iranologist Walther Hinz published in 1940 under the title “Engelbert Kaempfer: At the court of the Persian Great King (1684–1685) ”, is considered to be one of the most important German-language sources on Persia in the 17th century. In 2019 a German translation of the 5th book (Flora Japonica) was published with extensive commentary. After Meier-Lemgo's death in 1969, a phase of individual studies followed in the various specialist areas that are addressed in Kaempfer's works. The Engelbert Kaempfer Society, founded in Lemgo in 1971, also played an important role here.

After two international conferences in Lemgo and Tokyo on the occasion of the 300th anniversary of Kaempfer's landing in Japan, there was a renewed upswing in research on Kaemmer's life and writings. Thanks to the long-term cooperation of researchers from various disciplines, large parts of the legacy in the British Library , which were previously considered barely legible, were cataloged and made accessible in a critical edition (2001 to 2003). Among other things, there were considerable differences between the English print edition “The History of Japan” and Kaempfer's German manuscript “Today's Japan”. It was also shown that the fair copy of the manuscript in London was only partly made by Kaempfer, but also partly by his nephew and other scribes. Further volumes with Kaemmer's materials on Japanese plants, Siam, India and Russia followed.

In this context, several extensive publications emerged, including a biography of Detlef Haberland and anthologies in German and English. An English new translation made by B. Bodart-Bailey on the basis of the London manuscript ("Kaempfer's Japan: Tokugawa Culture Observed, 1999") expanded the international readership considerably.

In Japan, Tadashi Imai Kaempfer's work made known to the general public with his 1973 translation of Dohm's "History and Description of Japan". Hideaki Imamura contributed with a biography of Kaemmer's carpenters Imamura Eisei ( Imamura Eisei den , 2010) and the translation of extensive excerpts from the service diary of the Dejima trading office ( Oranda Shōkan Nisshi to Imamura Eisei, Imamura Meisei , 2007) to clarify the life and merits of his famous ancestors.

The analysis of the published writings and the estate, which has now lasted for over a century, shows the impressive breadth and depth of the research work of the Lemgo doctor, who is rightly one of the most outstanding explorers of the 17th century.

Honors

Carl von Linné named the genus Kaempferia of the ginger family (Zingiberaceae) in his honor . Other species named after Engelbert Kaempfer are the Japanese giant crab , Macrocheira kaempferi ( Temminck , 1836), and the Japanese larch , Larix kaempferi ( Lamb. ) Carrière .

The Engelbert-Kaempfer-Gymnasium in his hometown Lemgo is named after Engelbert Kaempfer .

In Lemgo there is the Engelbert Kaempfer monument on the wall. It was initiated, financed and inaugurated in 1867 by German naturalists and doctors. Gauleiter Alfred Meyer, under the patronage of Reichsleiter Alfred Rosenberg, put a memorial plaque on Kaempfer's birthplace - the current parish hall of the Church of St. Nicolai - in 1937. In 1991, the Engelbert-Kaempfer-Gesellschaft in Lemgo- Lieme put a board at the entrance of the former Kaempfer house. In 2009, Carolin Engels created an Engelbert Kaempfer memorial stone. He is in the Church of St. Nicolai near his now identified grave site.

Works

- Exercitatio politica de Majestatis divisione in realem et personalem, quam […] in celeberr. Gedanensium Athenaei Auditorio Maximo Valedictionis loco publice ventilendam proponit Engelbertus Kämpffer Lemgovia-Westphalus Anno MDCLXXIII d. June 8th mat. Dantisci [= Danzig], Impr. David Fridericus Rhetius.

- Disputatio Medica Inauguralis Exhibens Decadem Observationum Exoticarum, quam […] pro gradu doctoratus […] publico examini subject Engelbert Kempfer, LL Westph. ad diem April 22 […] Lugduni Batavorum [Leiden], apud Abrahanum Elzevier, Academiae Typographum. MDCXCIV.

- Amoenitatum exoticarum politico-physico-medicarum fasciculi v, quibus continentur variae relationes, observationes & descriptiones rerum Persicarum & ulterioris Asiae, multâ attentione, in peregrinationibus per universum Orientum, collecta, from auctore Engelberto Kaempfero. Lemgoviae, Typis & impensis HW Meyeri, 1712. ( diglib.hab.de ).

- Engelbert Kaempfer: 1651-1716. Strange Asia (Amoenitates Exoticae). Translated to a selection by Karl Meier-Lemgo, Detmold 1933.

- Engelbert Kaempfer: At the court of the Persian Great King (1684–1685) Ed. Walther Hinz, Tübingen 1977 and Stuttgart 1984.

- The History of Japan, giving an Account of the ancient and present State and Government of that Empire; of Its Temples, Palaces, Castles and other Buildings; of its Metals, Minerals, Trees, Plants, Animals, Birds and Fishes; of The Chronology and Succession of the Emperors, Ecclesiastical and Secular; of The Original Descent, Religions, Customs, and Manufactures of the Natives, and of thier Trade and Commerce with the Dutch and Chinese. Together with a Description of the Kingdom of Siam. Written in High-Dutch by Engelbertus Kaempfer, MD Physician to the Dutch Embassy to the Emperor's Court; and translated from his original manuscript, never before printed, by JG Scheuchzer, FRS and a member of the College of Physicians, London. With the Life of the Author, and an Introduction. Illustrated with many copperplates. Vol. I / II. London: Printed for the Translator, MDCCXXVII.

- Engelbert Kaempfers Weyl. DM and Hochgräfl. Lippischen Leibmedikus History and Description of Japan. Edited by Christian Wilhelm Dohm from the author's original manuscripts. First volume. With coppers and charts. Lemgo, published by Meyerschen Buchhandlung, 1777 ( digitized and full text in the German Text Archive ); Second and last volume. With coppers and charts. Lemgo, published by Meyerschen Buchhandlung, 1779. ( Digitized in the Bavarian State Library ).

- Dito. Reprint, with an introduction by H. Beck, 2 volumes, Stuttgart 1964 (= sources and research on the history of geography and travel. Volume 2).

-

Engelbert Kaempfer, works. Critical edition in individual volumes. Edited by Detlef Haberland , Wolfgang Michel , Elisabeth Gössmann .

- (Vol. 1/1, 1/2) Today's Japan. Munich: Iudicium Verl., 2001 (Wolfgang Michel / Barend Terwiel ed .; text volume and commentary volume). ISBN 3-89129-931-1

- (Vol. 2) Letters 1683-1715. Munich: Iudicium Verl., 2001. (Detlef Haberland ed.) ISBN 3-89129-932-X

- (Vol. 3) Drawings of Japanese plants. Munich: Iudicum Verl., 2003. (Brigitte Hoppe ed.) ISBN 3-89129-933-8

- (Vol. 4) Engelbert Kaempfer in Siam. Munich: Iudicum Verl., 2003. (Barend Terwiel) ISBN 3-89129-934-6

- (Vol. 5) Notitiae Malabaricae. Munich: Iudicum Verl., 2003. (Albertine Gaur ed.) ISBN 3-89129-935-4

- (Vol. 6) Russia diary 1683. Munich: Iudicum Verl., 2003. (Michael Schippan ed.) ISBN 3-89129-936-2

- Engelbert Kaempfer: The 5th fascicle of the "Amoenitates Exoticae" - Japanese botany. Edited and commented by Brigitte Hoppe and Wolfgang Michel-Zaitsu. Hildesheim / Zuerich / New York: Olms-Weidmann, 2019. ISBN 978-3-615-00436-6

literature

- Karl Meier-Lemgo: Kaempfer, Engelbert. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 10, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1974, ISBN 3-428-00191-5 , p. 729 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Beatrice M. Bodart-Bailey: Engelbert Kaempfer. World traveler of the 17th century , Detmold 2010.

- Gerhard Bonn: Engelbert Kaempfer (1651–1716): the traveler and his influence on the European awareness of Asia. With an escort by Josef Kreiner. (Additional dissertation at the University of Münster 2002). Lang, Frankfurt am Main among others 2003

- JZ Bowers, RW Carrubba: The doctoral thesis of Engelbert Kaempfer on tropical diseases, oriental medecine and exotic natural phenomen. In: Journal of the history of medecine and allied sciences. Vol. XXV 1970, No. 3, pp. 270-311.

- Heinrich Clemen: Engelbert fighters. In memory of his fellow citizens and compatriots. Lemgo 1862 ( digitized version )

- Andreas W. Daum : German Naturalists in the Pacific around 1800. Entanglement, Autonomy, and a Transnational Culture of Expertise. In: Hartmut Berghoff, Frank Biess, Ulrike Strasser (ed.): Exploration and entanglements: Germans in Pacific Worlds from the Early Modern Period to World War I . Berghahn Books, New York 2019, pp. 79-102 (English).

- Michael Eyl: Sino-Japanese acupuncture in France (1810-1826) and its theoretical basis (1683-1825). Diss. Med. Zurich 1978.

- Rudolf Falkmann: Fighter, Engelbert . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 15, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1882, pp. 62-64.

- Detlef Haberland (ed.): Engelbert Kaempfer - work and effect. Lectures at the symposia in Lemgo (September 19-22, 1990) and Tokyo (December 15-18, 1990). Franz Steiner, Stuttgart 1993.

- Detlef Haberland (ed.): Engelbert Kaempfer (1651–1716): a learned life between tradition and innovation. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2005. ISBN 3-447-05128-0

- Johann Barthold Haccius: The best journey of a Christian fighter to the heavenly Orient ... (funeral sermon). Lemgo 1716 ( LLB Detmold )

- Theodor Heuss : Engelbert fighters. In: Ders .: Shadow conjuring. Figures on the margins of history . Wunderlich, Stuttgart / Tübingen 1947; Klöpfer and Meyer, Tübingen 1999, ISBN 3-931402-52-5

- Engelbert Kaempfer on his 330th birthday. Collected contributions to Engelbert Kaempfer research and the early days of Asian research in Europe , ed. in connection with the Engelbert-Kaempfer-Gesellschaft Lemgo e. V. German-Japanese Circle of Friends, compiled and edited. by Hans Hüls and Hans Hoppe (= Lippische Studien, Vol. 9), Lemgo 1982.

- Peter Kapitza : Engelbert Kaempfer and the European Enlightenment. In memory of the Lemgo traveler on the occasion of his 350th birthday on September 16, 2001. Iudicum Verlag, Munich, ISBN 3-89129-991-5

- Sabine Klocke-Daffe, Jürgen Scheffler, Gisela Wilbertz (eds.): Engelbert Kaempfer (1651–1716) and the cultural encounter between Europe and Asia (= Lippische Studien, Vol. 18), Lemgo 2003.

- Wolfgang Michel : Prostratio and pickled herring dance - Engelbert Kaempfer's experiences in the castle of Edo and their background . Japanese Society for German Studies (Hrsg.): Asiatic Germanist Conference in Fukuoka 1999 Documentation. Tōkyō: Sanshūsha, 2000, pp. 124-134. ISBN 4-384-040-18-0 C3848 ( digitized version )

- Wolfgang Michel, Torii Yumiko, Kawashima Mabito: Kyushu no rangaku - ekkyō to Koryu ( ヴォルフガング·ミヒェル·鳥井裕美子·川嶌眞人共編「九州の蘭学ー越境と交流」 , dt Holland customer in Kyushu - border crossing and exchange.) . Shibunkaku Shuppan, Kyōto, 2009. ISBN 978-4-7842-1410-5

- Wolfgang Michel: Medicine, remedies and herbalism in the Euro-Japanese cultural exchange of the 17th century. In: HORIN - Comparative Studies on Japanese Culture, No. 16, 2009, pp. 19-34

- Lothar Weiss: The exotic delicacies of Engelbert Kaempfer . Publishing house for regional history, Bielefeld 2012

- Wolfmar Zacken: The fighter prints . Edition Galerie Zacke 1982

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Gisela Wilbertz: Engelbert Kaempfer and his family . In: Heimatland Lippe . Issue 12/2004.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Herbert Stöver: Engelbert Kaempfer's journey around half the world . In: Heimatland Lippe . Issue 12/1990.

- ↑ See on this Josef Wiesehöfer: A me igitur ... Figurarum verum auctorem ... nemo desideret - Engelbert Kaempfer and the old Iran. In: Haberland (1993), pp. 105-132.

- ↑ Kaempfer's cuneiform inscription with translation can be found in Weiß (2012), pp. 130f.

- ^ Detlef Haberland : Kaempfer, Engelbert. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 713.

- ↑ See the Notitiae Malabaricae (Kaempfer, Critical Edition, Volume 5)

- ↑ On Kaempfer's Japanese helpers see Wolfgang Michel: Zur Erforschung Japans durch Engelbert Kaempfer . In: Engelbert Kaempfer, Werke, Vol. 1/2 (Today's Japan), pp. 76–89

- ↑ For the background to this tolerance of plant studies, see Michel (2009).

- ↑ On these audiences and their background, see Michel (2000)

- ↑ A detailed analysis of the work can be found in Wei (2012)

- ↑ On Scheuchzer and the History of Japan see Wolfgang Michel: Johann Caspar Scheuchzer (1702-1729) and the publication of the History of Japan. In: Asiatische Studien / Études Asiatiques, Vol. LXIV, 1/2010, pp. 101-137.

- ^ Wolfgang Michel: Christian Wilhelm Dohm's documents. In: Engelbert Kaempfer, Werke, Vol. 1/2 (Today's Japan), pp. 53–72

- ↑ A comprehensive new edition of the studies promoted during the 80s and 90s appeared in 2001. Kapitza: Engelbert Kaempfer and the European Enlightenment.

- ↑ Reinard Zöllner: Locked against knowledge - What Japan learned about itself from Kaempfer. In: Sabine Klocke-Daffa; Jürgen Scheffler; Gisela Wilbertz (ed.) Engelbert Kaempfer (1651–1716) and the cultural encounter between Europe and Asia. Akihide OSHIMA: Sakoku to iu gensetsu ( Sakoku as Discours). Minerva, Kyoto, 2009

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Michel: On the Background of Engelbert Kaempfer's Studies of Japanese Herbs and Drugs. Nihon Ishigaku Zasshi - Journal of the Japan Society of Medical History , 48 (4), 2002, pp. 692-720.

- ↑ See Wolfgang Michel: On Engelbert Kaempfer's "Ginkgo" ( digitized version )

- ↑ More from Wolfgang Michel: Engelbert Kaempfers preoccupation with the Japanese language. In: Haberland (1993), pp. 194-221.

- ↑ a b c d Wolfgang Michel: Engelbert Kaempfer and medicine in Japan. In: Haberland (1993), pp. 248-293.

- ↑ In contrast to “derivative” (derived). See under Willem ten Rhijne .

- ↑ Translated from the Lemgo edition 1712 Amoenitatum exoticarum politico physico medicarum fasciculi V. , p. 598.

- ↑ Kaempfer 1712, p. 587.

- ↑ Kaempfer 1712, pp. 582-589.

- ↑ Eyl 1978, pp. 28-31

- ^ Ralf Bröer: Engelbert Kaempfer. In: Wolfgang U. Eckart , Christoph Gradmann (Hrsg.): Ärztelexikon. From antiquity to the present. 3. Edition. Springer Verlag, Heidelberg / Berlin / New York 2006, p. 188 f. Medical glossary 2006 , doi : 10.1007 / 978-3-540-29585-3 .

- ↑ Kaempfer interpreted the component bushi as a soldier and explains yamabushi as a "mountain soldier". In fact, it is another homophonic word meaning to hide, to prostrate oneself, which alludes to ascetic practices. In this respect, Yamabushi are people who prostrate themselves in the mountains, hiding.

- ↑ Kapitza (2001)

- ↑ Michel (2000)

- ↑ a b Stefanie Lux-Althoff: The research trips of Engelbert Kaempfer . In: Heimatland Lippe . Issue 6/7 2001.

- ↑ The auction catalog is in the Lemgo City Archives, signature A 989

- ^ The register in the Lippische Landesbibliothek Detmold, the divorce process in the Landesarchiv NRW department Ostwestfalen-Lippe, Detmold location

- ↑ See Engelbert Kaempfer, Werke. Critical edition in individual volumes

- ↑ For this translation see W. Michel: His Story of Japan - Engelbert Kaempfer's Manuscript in a New Translation . Monumenta Nipponica, 55 (1), 2000, pp. 109-120. ( Digitized version )

- ^ Carl von Linné: Critica Botanica . Leiden 1737, p. 93

- ↑ Carl von Linné: Genera Plantarum . Leiden 1742, p. 4

- ↑ From the Pyleren in front of the castles - Engelbert-Kämper-Ehrung, FL Wagener Lemgo, Lemgo, 1938, p. 4.

- ↑ Scheffler, Jürgen: Karl Meier, Engelbert Kaempfer and the culture of remembrance in Lemgo 1933 to 1945. In: Klocke-Daffa, Sabine, Scheffler, Jürgen, Wilbertz, Gisela (eds.) Engelbert Kaempfer (1651-1716) and the cultural encounter between Europe and Asia, Lippe Studies Vol. 18, Landesverband Lippe, Lemgo 2003, p. 320.

- ^ Engelbert Kaempfer Society

Web links

- Literature by and about Engelbert Kaempfer in the catalog of the German National Library

- Author entry and list of the described plant names for Engelbert Kaempfer at the IPNI

- Kaempfer project at the University of Bonn

- Engelbert Kaempfer Society Lemgo eV

- Wolfgang Michel about Engelbert Kaempfer: life, works, reception, bibliography, script samples (German, English and Japanese)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Kaempfer, Engelbert |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German scholar and explorer (Russia, Persia, India, Siam, Japan) |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 16, 1651 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Lemgo , Germany |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 2, 1716 |

| Place of death | Lieme |