Moxibustion

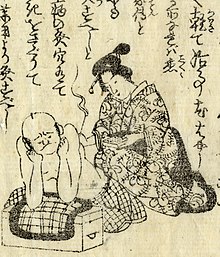

Moxibustion , also called moxa therapy or moxing for short , describes the process of warming up special points on the body. The therapy was developed in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), but has undergone further changes in the surrounding countries, especially in Japan.

General

In China, moxibustion is respected as a therapy on an equal footing with acupuncture when indicated . The generic term zhēn jiǔ ( Chinese 針灸 ), which is often shortened as acupuncture in Western publications, includes not only the needle ( 針 , zhēn ) but also the moxa ( 灸 , jiǔ ) and means something like “needles and burning”. The western word moxibustion is made up of Japanese 艾 mogusa , which denotes the dried and finely grated fibers of mugwort leaves ( Artemisia princeps , Japanese ヨ モ ギ yomogi ), and Latin combustio (“to burn”). The effectiveness of moxa therapy has been the subject of scientific research since the early 20th century.

During moxibustion, small amounts of dried, fine mugwort fibers (moxa) burn up on or above certain therapy points. According to traditional Chinese teachings, the heat acts on the flow of 'Qi in the underlying channels (also meridians ). In addition to these points, which are mainly used for moxibustion, there are other points that are reserved for acupuncture. The mugwort ( Artemisia vulgaris , several varieties are used in East Asia) have long been considered a medicinal and aromatic plant in the East and West. The leaves collected in spring are dried, cleaned, grated and made into a fine cotton wool. A uniform consistency of the fibers as well as their fineness, which determines the firing temperature, is important for even smoldering.

history

As early as the 16th century, Portuguese Jesuits reported from Japan that illnesses were treated there with "fire buttons" ( botoẽs de fogo ). Moxa became generally known in Europe in the second half of the 17th century through a book by the Batavian pastor Hermann Buschoff . Engelbert Kaempfer published in his work Amoenitates Exoticae (1712) an essay with a Japanese mirror of moxibustion points ( 灸 所 鑑 kyūsho kagami ), which lists 60 treatment points. The therapy, which was fiercely discussed in Central Europe in the 17th century, was temporarily given less attention towards the end of the 18th century.

The first modern scientific work on moxibustion was the dissertation of the Japanese doctor Hara Shimetarō in 1929.

Forms of application

Treatment with moxa cones

In the case of indirect burning, the therapist places ginger slices on the relevant therapy points and ignites these small cones made of moxa, which slowly fade away. As soon as the patient feels a sensation of heat, the cone is pushed to the next therapy point. Each point is heated several times until the skin is clearly reddened. In this "indirect moxibustion", the moxa has no contact with the skin. Today the specialist trade also sells finished cones glued to paper discs.

In China and Japan, people still put the cone directly on the skin ("direct moxibustion"). The initially resulting burn blisters as well as small inflammations are intended to stimulate the body's defenses. Later, a small crust will form on the affected area.

Moxa cigar

The therapist lights a moxa cigar (rods of moxa rolled in thin paper) and brings the glowing tip closer to the therapy point to about half a centimeter. If the patient feels a distinct sensation of heat, he briefly removes the tip. The procedure is repeated until the skin at the therapy point is clearly reddened.

Moxa needles

This is an invention of the Japanese therapist Akabane Kōbei / Kōbē (1895–1983) from the 1920s. With special steel needles to which the glowing moxa is attached, the therapist directs the heat in a concentrated manner to the relevant therapy point.

Moxa patch

These are plasters, the adhesive side of which is coated with medicinal herbs. These generate a heat reaction and are stuck to the relevant therapy points.

effect

The moxa contains, among other things, essential oils , including cineole and thuja oil , as well as choline , resins and tannin . In traditional Chinese medicine, moxa stimulates the flow of 'Qi and works against so-called "cold" states. Dr. Hara Shimetar ō , who rejected the conventional meridian system, demonstrated a number of effects in direct moxibustion (increase in white and red blood cells, faster coagulation of the blood, increase in calcium, higher capacity in the production of antibodies, etc.). One theory put forward by Westerners is that the heat stimulates the nerve endings in the skin, which could stimulate the pituitary and adrenal glands to release hormones .

Indications and contraindications

According to its proponents, the main areas of application of moxa therapy are: weakness after chronic diseases and diseases of the respiratory tract such as chronic bronchitis and asthma . Moxa should not be used on the face, head, or near mucous membranes. This technique should also not be used in the event of a fever, acute inflammation, insomnia or during menstruation . During pregnancy, the moxibustion of the zhiyin point is used in the breech position to cause the child to turn into the skull position .

In China and many surrounding countries, moxa is used not only for healing, but also to prevent diseases. There is a saying that one should not undertake a long journey without first stimulating the 'qi through moxa.

Risks

As a result of skin burns caused by moxibustion, scars often remain, which is why some users place a piece of ginger root or garlic on the skin under the moxa as a preventive measure . Corresponding scars in children can be mistaken for the consequences of abuse, for example being burned by cigarettes.

Although the use of such moxibustion techniques on children is seldom seen as child abuse , it nonetheless raises considerable moral and legal problems. Any bodily harm carries the risk of undesired complications (e.g. infection of the wounds) with potentially dangerous consequences. Scars can potentially be cosmetically disfiguring for life. Only with the informed consent of the child (or the legal representative) and medically correct implementation, such an intervention is not a criminal offense. Since the effectiveness of moxibustion cannot be scientifically proven, according to the prevailing opinion (in Germany) it is impossible to carry it out properly. It is therefore at least doubtful whether parents who have the operation carried out on their child are living up to their parental responsibility.

The incineration also produces substances and dusts or fine dusts that can be inhaled during the treatment. Model calculations show that the smoke exposure resulting from moxibustion is comparable to passive smoking in restaurants and discos.

See also

Web links

- UA Casal: Acupuncture, Cautery and Massage in Japan . (PDF; 1.1 MB) In: Asian Folklore Studies. Vol. 21, 1962, pp. 221-235

Remarks

- ↑ the 'u' is hardly pronounced or not pronounced at all

Individual evidence

- ↑ The Japanese doctor Hara Shimetarō carried out the first scientific studies at the Imperial University of Kyushu. He is also the first to do a doctorate on this subject (1929)

- ↑ Wolfgang Michel: Japan's role in the early communication of acupuncture to Europe. German journal for acupuncture , Vol. 36, No. 2, April 1993, pp. 40-46. Ders .: Early Western observations on acupuncture and moxibustion . In: Sudhoffs Archiv , Volume 77 (2), 1993, pp. 194-222.

- ↑ Wolfgang Michel: Hermann Buschof - The precisely examined and invented Podagra, mediating yourself safely = own recovery and relieving Huelff = means . Haug Verlag, Heidelberg 1993, 148 pp.

- ^ Hermann Buschoff: The gout, more narrowly searcht, and found out; together with the certain cure thereof . London 1676. W Michel, ed. Fukuoka, March 2003, hdl: 2324/2936 (PDF; 10.6 MB)

- ↑ Wolfgang Michel: Engelbert Kaempfer's strange moxa mirror - repeated reading of a German travel book of the Baroque period . In: Dokufutsu Bungaku Kenkyū , No. 33, 1983, pp. 185-238, hdl: 2324/2999 (PDF)

- ^ W. Michel: Far Eastern Medicine in Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Century Germany . hdl: 2324/2878 (PDF; 8 MB)

- ↑ See an English summary of Hara's findings . Next Shinichirō Watanabe; Hiroshi Hakata; Takashi Matsuo; Hiroshi Hara; Shimetaro Hara: Effects of Electronic Moxibustion on Immune Response. Zen Nihon Shinkyu Gakkai zasshi (Journal of the Japan Society of Acupuncture and Moxibustion) Vol. 31, No. 1: 42-50 (1981)

- ↑ See a more recent work: ME Coyle, CA Smith, B. Peat: Cephalic version by moxibustion for breech presentation. In: The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. Number 2, 2005, p. CD003928, ISSN 1469-493X . doi: 10.1002 / 14651858.CD003928.pub2 . PMID 15846688 . (Review).

- ↑ D. Fisman: Unusual skin findings in a patient with liver disease. In: CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association journal = journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. Volume 166, Number 12, June 2002, p. 1567, ISSN 0820-3946 . PMID 12074126 . PMC 113805 (free full text).

- ^ Nhu Chau: Moxibustion burns. In: Journal of Hospital Medicine. 1, 2006, pp. 367-367, doi: 10.1002 / jhm.138 .

- ↑ L. Condé-Salazar, MA González, D. Guimarens, C. Fuente: Burns due to moxibustion . In: Contact Dermatitis , 1991 Nov., 25 (5), pp. 332-333, PMID 1809540

- ^ Margaret M. Lock: Scars of Experience: The Art of Moxibustion in Japanese Medicine and Society. Culture . In: Medicine and Psychiatry , 2, 1978, pp. 151-175

- ↑ a b Kenneth Feldman: Pseudoabusive Burns in Asian Refugees . In: American Journal of Diseases of Children , 138, 1984, pp. 768-769

- ^ Ian A. Canino, Jeanne Spurlock: Culturally Diverse Children and Adolescents. Assessment, Diagnosis, and Treatment . Guilford Press, New York NY 1994

- ↑ B. Herrmann: Medical diagnostics for physical child abuse . In: Pediatrician , 36th year, 2005, No. 2

- ↑ KM Look, RM. Look: Skin scraping, cupping, and moxibustion that may mimic physical abuse . In: J Forensic Sci. , 1997 Jan, 42 (1), pp. 103-105, PMID 8988581

- ^ HC Wong, JK Wong, NY. Wong: Signs of physical abuse or evidence of moxibustion, cupping or coining? In: CMAJ , 1999 Mar 23,160 (6), pp. 785-786, PMID 10189420

- ↑ Udo Eickmann, Matthias Kaul, Quian Zhang, Eberhard Schmidt: Air pollution from pyrolysis products in treatment methods of traditional Chinese medicine. In: Hazardous substances - keeping the air clean , Volume 70, No. 6, 2010, pp. 261–266, ISSN 0949-8036