Philipp Franz von Siebold

The portrait is based on a chalk drawing that Joseph Schmeller made on May 16, 1835 in Weimar.

Philipp Franz Balthasar Siebold , von Siebold from 1801 , (born February 17, 1796 in Würzburg , † October 18, 1866 in Munich ) was a Bavarian doctor , Japan - and natural scientist, ethnologist , botanist and collector . He lived in Japan from 1823 to 1829 and from 1859 to 1862. Siebold is one of the most important witnesses of the isolated Japan of the late Edo period and is also highly revered in today's Japan. He is considered the founder of international research on Japan . Its official botanical author abbreviation is " Siebold "; earlier the abbreviation “ sieve. “Used.

Life

education

Siebold's father was the renowned physician and first Würzburg physiologist (Johann) Georg Christoph Siebold (1767–1798), the founder of a maternity hospital established in the Würzburg Freihaus at Innere Graben 18 on December 17, 1791 (the year of his inaugural lecture) and which existed until 1805 , a grandson of Carl Caspar von Siebold , the founder of modern surgery. His mother was his wife Apollonia, née Lotz. Philipp's parents had married on January 19, 1795 and shortly afterwards they moved into an apartment on Würzburger Marktgasse. He was baptized on the day of his birth in the Würzburg Cathedral . After the early death of the father and after the move in 1805, Appolonia and Philipp moved to Heidingsfeld near Würzburg, from 1809 Franz Joseph Lotz, a brother of Appolonia, who had been transferred to Heidingsfeld as pastor in 1808, took over the upbringing and promotion of the boy . Philipp and his mother lived in his house from 1809 onwards. Philip's uncle tried to reconcile the advantages of Christian social teaching with the achievements of his Enlightenment era.

After the Latin school and the royal grammar school he attended from the age of 13 , Philipp Franz von Siebold studied medicine at the Julius Maximilians University in Würzburg in 1816 - the Siebolds had meanwhile been elevated to the hereditary nobility - where future healers also studied botanicals Knowledge was imparted and where, in addition to medicine, he dealt with natural sciences, geography and ethnology and obtained his medical doctorate in 1820. He became a doctor of medicine, surgery, and childbirth. The precision learned at the university in handling the pencil should prove to be valuable. Since 1816 he was a member of a striking student union , the Corps Moenania Würzburg . He was a member of the Society of German Natural Scientists and Doctors .

Professional background

After receiving his doctorate in 1820, he worked briefly as a general practitioner in Heidingsfeld. Two years later he received an offer from the Dutch military leadership for a medical officer position in East India. He applied with the words: "It was natural history ... that determined me to take such a step into other parts of the world and it will also be the reason for the possibility of effective results from my travels."

Appointment as medical officer

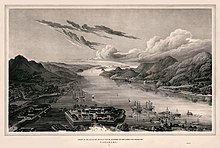

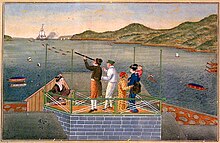

In 1822 he followed the call to The Hague , where he was appointed Chirurgijn-Majoor in the Dutch-Indian army by royal decree on July 21 . He had been given the prospect of doing natural research in the colonies. In 1822 he was elected a member of the Leopoldina . In those years the Dutch carried out a reassessment of their colonial policies and overseas possessions. When he arrived in Batavia , the governor-general Godert van der Capellen offered him a job as a doctor at the Dejima factories , a small artificial island in the bay of Nagasaki , and provided financial means so that Siebold would carry out extensive examinations of the country and its people. Western medicine, science, weapons technology, and mathematics have long been valued in Japan, and educated Europeans were in demand for advice. The doctors on Dejima, who had nothing to do with the trade, were frequently called to see high-ranking Japanese patients, giving them more opportunities than the commercial staff to make friends and gather information and materials. Some of them made a name for themselves as Japanese researchers. Siebold's activities are part of a long tradition of exploring the country by trading doctors from the Dutch East India Company , which began in 1650/51 with the wound surgeon Caspar Schamberger . At the beginning of the 18th century, the doctor Engelbert Kaempfer (1651-1716) set the first major milestone with his book published in 1727 as the "History of Japan". Towards the end of that century, the Swedish doctor Carl Peter Thunberg (1743–1828) caused a sensation with a scientific travel book and a "Flora Japonica", while Siebold's studies of Japanese fauna and flora as well as his vast natural and regional Japanese collection are still valuable today have not lost.

First stay in Japan

Siebold's first stay in Japan lasted from August 11, 1823 to January 2, 1830. Officially, only Dutch people from the “ Western World ” were allowed to step on Japanese soil. Siebold's knowledge of Dutch was poorer than that of the Japanese interpreters at the time of his arrival, but, as in similar cases before, the landing was tacitly accepted.

Like almost all of his predecessors, he soon enjoyed excellent relationships with Japanese scholars, doctors and some sovereigns interested in the West. Actually, the Europeans who work in the Dejima trading post could only leave this small island once or twice a year for day trips or for the Suwa Shrine festival, which is important for the city . The reasons are not clear, but with the permission of the Nagasaki governor appointed by the central government, Siebold was allowed to set up a kind of school in a small property in front of the city in Narutaki, where he gave weekly classes in Dutch on Western natural history and medicine. The instructions mostly took place during the treatment of the patients, who came from near and far. However, one should not overlook the fact that the young doctor's experience was not always sufficient, which Siebold was well aware:

- “(February 25, 1826) Very early in the morning my students and other doctors from the area came with their sick people and asked me for advice and help. As usual, they were chronic, neglected, and incurable diseases, and the lengthy consultations required a great deal of time and patience. I did everything for the sake of my students, whose good reputation would have suffered if their patients, whom they had put off for me and often brought from distant places, had left with advice and helplessness. So I often had to play the charlatan against my will. ”- Siebold: Nippon. P. 117.

Many of his therapies stayed within the framework created by his predecessors. Siebold tried a vaccination for the first time , which was unsuccessful due to the unusable serum. From the beginning he did not accept any payment for his medical treatment. The patients, socialized in a gift exchange culture, tried to convey their gratitude through gifts. As Siebold's interests soon became known, he received numerous objects for his ethnographic and natural history collection. Since the 17th century, the sale of all Japanese works relating to the administration, topography , history of the country, religion, the arts of war and court life to foreigners has been strictly prohibited. Religious objects, weapons, coins, maps and even miniatures were also confiscated upon departure. Nevertheless, Siebold was able to put together a rich collection. Specially committed hunters roamed the forests, and assistants instructed by him prepared the hides and skeletons of the zoological harvest. Siebold's students had ample opportunity to observe how a European explored the country and its people. They, too, provided valuable help with 'dissertations' on a wide variety of cultural topics, which they wrote in Dutch.

In 1826, the factory manager's court trip to Edo , which was then carried out every four years, was due. Since the 17th century he took the trading doctor and two or three other Europeans with him. With a large group of Japanese escorts, they traveled overland from Nagasaki to Kokura (see Nagasaki Kaidō ) and crossed over to Shimonoseki , from where the journey by ship to Osaka was continued. Then it went over the famous "East Sea Road" Tōkaidō to Edo. The highlight of the stay was the reverence of the factories leader Johan Willem de Sturler at the Shogun Tokugawa Ienari . The “Hofreise” was the only opportunity for the chosen few Europeans to get to know the interior of the country. Like Engelbert Kaempfer and Carl Peter Thunberg , Siebold also used this opportunity as much as possible. At that time there lived in Edo a number of well-educated “Dutch experts ” ( Rangakusha ) with a good knowledge of the Dutch language, who visited the delegation's accommodation, the so-called Nagasaki hostel ( Nagasakiya ). In his work NIPPON , Siebold also describes the visits of high-ranking, inquisitive personalities such as the sovereign of Nakatsu , Okudaira Masataka , and his father, the powerful sovereign of Satsuma , Shimazu Shigehide . Like Kaempfer and other travelers to Japan, Siebold quickly noticed that although there were strict regulations and instructions to prevent contacts and research into the country, these were only followed on a case-by-case basis in everyday life:

- “Exploring the country, researching the state and church constitution, warfare and other political conditions and institutions are strictly forbidden to strangers, and the strictest laws forbid subjects to inform them about it or even to assist them in any way with their research . Our Japanese companions on the journey to court are sworn to observe such ordinances closely, and they may and may not allow us to step beyond the limits of literal law without jeopardizing their own existence. These people, however, who through contact with educated Europeans have widened the range of their political views and have learned only too well to understand the narrow-mindedness of such precautions on the part of their government, in most cases merely adhere to the form of the law and see us where it is is only ever possible through the fingers. Without such indulgence, any scientific research would be impossible for a stranger to Japan, because strictly speaking, any contact with the country and its people is forbidden. ”- Siebold: Nippon. P. 108.

The circle of those Japanese who are now considered direct students consists of 53 people. In addition, there were around 25 Japanese scholars, predominantly fans of Dutch studies ( Rangaku ), several Japanese rulers and not to forget the painter Kawahara Keiga , who had previously worked for Johan Frederik van Overmeer Fisscher and now made a large series of pictures for Siebold.

Japanese partner

Since the landing of European women on Dejima was forbidden, some of the better-off servants entered into temporary liaison with local women from the Maruyama district who had access to the trading post. Siebold established a relationship with Sonogi O-Taki (later Kusumoto Taki, 楠 本 滝 , 1807-1865), after whom he named a hydrangea as Hydrangea Otaksa (today: Hydrangea macrophylla 'Otaksa' ). In 1827 the daughter Ine (O-Ine) was born, who like her mother had to stay in the country according to the Japanese regulations when Siebold started the journey home.

"Siebold Affair"

In 1828 Siebold's official service in Japan came to an end. His treasures were loaded more or less concealed, but on August 10, shortly before leaving the port, the Cornelius Houtman was driven ashore by a typhoon and was unable to maneuver. When the cargo was brought ashore to get the ship afloat, it could not be overlooked that Siebold's luggage contained maps and other items whose export was strictly forbidden. This so-called "Siebold Affair" had serious consequences for him and his circle of friends. About fifty people who had been in close contact with him were given harsh punishments, including banishment. The astronomer Takahashi Kageyasu , who had provided Siebold with the latest maps from Ino Tadataka in exchange for Krusenstern's report of his circumnavigation, died in custody. His body was placed in brine until sentenced. Siebold confessed his guilt, but gave no names and at the same time applied for naturalization . After long negotiations, he was exiled from Japan on October 22, 1829 for life. On January 2, 1830, his ship ran out.

Siebold's collection

Siebold's collection was returned to him on departure:

- 187 (200?) Specimens from 35 mammalian species

- 827 (900?) Bellows of 188 bird species

- 540 (750?) Pieces out of 203 species of fish

- 166 (170?) Pieces of 28 reptile species

- over 5,000 invertebrates ( mollusks , crustaceans , insects , etc.)

- 800 live specimens of 500 plants TYPES

- approx. 12,000 dried herbarium specimens of 2,000 plant species

Siebold's ethnographic collection was further expanded in Europe. After incorporating parts of the collections of Jan Cock Blomhoff and Johannes (Jan) Frederik van Overmeer Fisscher and through acquisitions in St. Petersburg, it counted around 5,000 objects, which he arranged in four groups of 10 departments each (books, maps, coins, economic products , Everyday and art objects, tools with raw materials, models of buildings and ships, etc.)

For the first time in more than 100 years, Siebold's second collection (from his second trip to Japan) will be exhibited in the Museum Five Continents in 2019 .

Work and impact in Europe

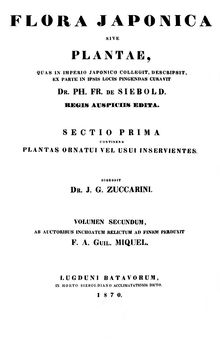

On his return, the Dutch government gave Siebold unlimited leave to organize and evaluate his collections. Moreover, after the results of his research had gradually reached the public, he was given high honors. After he had completed the list of his collections, Siebold devoted himself to the publication of his works. The Fauna Japonica ( Mammalia , Aves , Pisces , Reptilia ) , which was published with the help of Coenraad Jacob Temminck, Hermann Schlegel and Wilhem de Haan, and the Flora Japonica published together with Joseph Gerhard Zuccarini, caused a sensation among naturalists . There was also an atlas of the Japanese Empire and the comprehensive work Nippon. Archive describing Japan , which he published in nine sections between 1832 and 1858. Siebold was awarded the Order of Merit of the Bavarian Crown as early as 1832 .

Many important garden plants such as hydrangea , hosta , bluebell tree and Japanese knotweed , which is now growing wild in Germany as an invasive neophyte , came to Europe through the Siebold Society and Siebold's acclimatization garden in Leiden .

Siebold was neglected for a long time in the history of science in Germany, but his scientific contribution to Japan is quite comparable with the achievements of explorers like Alexander von Humboldt . Today Siebold is considered to be the pioneer of Japanese studies . In Bonn, for example, he was offered a professorship in Japanese Studies, which would have been the first in Europe, but he turned down the position because he did not want to "saddle from horse to donkey". During his time in East Asia, Siebold collected countless objects from art and everyday life, in keeping with his encyclopedic claim. Back in Europe he sold parts of the collections, including a. to the royal and imperial courts in Holland and Vienna . The proceeds made it possible for him to have a pleasant “retirement life”, which he mainly filled out with botanical studies. His objects still form the basis of the Japanese collections of some important museums in Europe (e.g. the ethnological museums in Leiden and Munich ).

In 1845 Siebold married Helene von Gagern (1820–1877). From this marriage three sons and two daughters were born.

Siebold's contribution to the opening of Japan

Siebold was convinced that opening up Japan to other countries would be beneficial for all sides, and he followed the advances of the Western powers with great attention. Although the politician and scholar Shigenobu Okuma (1838–1922) drew attention to his role in the book Kaikoku Taiseishi in 1913 , Siebold's achievements have only recently been documented by relevant sources. At first he made himself useful as an advisor in the Dutch Colonial Ministry. At his suggestion, King Wilhelm II sent a letter to the Shogun in Edo in 1844. Between 1852 and 1855, Siebold was able to help with the preparations for the Russian expedition under Vice-Admiral Evfimi Wassiljewitsch Putjatin with his knowledge of the country. The Russian negotiations in Japan were crowned with the conclusion of the Shimoda Treaty . Three treaties that Japan concluded in 1854 and 1855 with the United States of America ( Treaty of Kanagawa ), Great Britain ( Treaty of Nagasaki ) and Russia opened up Japanese ports and gradually eased restrictions on exchanges with foreign countries.

Second stay in Japan

In 1858 the Japanese government finally allowed Siebold to re-enter. In the meantime he had become famous as a Japan researcher, which was also known in Japan. He had actually hoped to move to Japan as Consul General, but the Dutch East India Company had been re-privatized in 1855, so he left as its “agent”. During this second stay, which lasted from August 4, 1859 to the end of April 1862, he kept a diary. Of course, there were reunions with former students and his daughter Kusumoto Ine. Temporarily he was active as an advisor to the government, but the quarrels and disagreements soon increased, and he also got caught up in the rivalries of the western powers struggling for influence. Siebold left the country on November 24, 1862. A year later, at his own request, he was released from the Dutch civil service.

Siebold's sons

On his second trip to Japan Siebold took his eldest son Alexander George Gustav von Siebold (1846–1911) with him, who quickly learned the Japanese language and was employed by Alcock in the English embassy in 1861. In 1867 he traveled to Europe as an interpreter for a Japanese embassy, and from 1870 to 1911 he was in the diplomatic service of the Japanese government. Heinrich (Henry) v. Siebold (1852–1908) accompanied his brother Alexander in 1869, who returned to Japan that year. He did not have a formal education either, but found a job as a local interpreter at the Austro-Hungarian legation. He developed into an important collector and is today, along with Edward S. Morse, the founder of modern archeology in Japan. Both sons published a new edition of the work Nippon in 1896 on the occasion of the 100th birthday of their father .

tomb

Siebold died in Munich in 1866. His grave is in the Old Southern Cemetery in Munich (Grave field 33 - row 13 - place 5) location .

For the hundredth birthday in Tokyo in 1896 a memorial service was held in the traditional hotel "Ueno Seiyōken".

effect

Although Siebold's catchphrase was circulating for a long time in Japan as the “bearer of modern medicine”, his contribution in this regard is now viewed very cautiously. He exerted a much stronger effect on his students through his broad horizon and exemplified research activity, which included natural sciences as well as ethnology. His botanical activities triggered a significant boost in the modernization of Japanese botanical science through his student Itō Keisuke (1803-1901), who founded the Red Cross in Japan with Siebold's son Alexander. The early modern exploration of the archipelago's flora, initiated by Andreas Cleyer , George Meister and Engelbert Kaempfer and anchored in Linné's taxonomy by Carl Peter Thunberg, culminated in the Flora Japonica written by Siebold and Zuccarini .

Siebold's natural and regional history collections are still not exhausted. Research on Japan still finds a material foundation here for opening up Japan in the early 19th century. At the same time, Siebold was the first among the western travelers to Japan of the Edo period to focus on the neighboring countries and regions of Ryūkyū (today Okinawa Prefecture ), Korea and Ezo (today Hokkaidō ).

Letters from Philipp Franz von Siebold were edited by Genji Kuroda and Herta von Schulz, while Kuroda was the director of the Berlin Institute for Japan.

The Philipp Franz von Siebold Prize was donated in 1978 by the then German Federal President Walter Scheel on the occasion of his state visit to Japan. It is awarded annually to a Japanese scientist who has made special contributions to a better mutual understanding of culture and society in Germany and Japan.

Taxa named after Siebold

Many plant and animal species are named after Philipp Franz von Siebold (for information on the authors, see the list of botanists and zoologists ):

| scientific name | German name | if necessary, references to external descriptions |

|---|---|---|

| Siebold's spring damsel (Japan's largest dragonfly) | in engl. Wikipedia | |

|

Siebold's worm fern or steep worm fern | external and external (there in the middle of the page) |

|

Siebold's Felsflur-Sackträger (a small butterfly) | external |

| White-edged Funkie | ||

|

= Sedum Sieboldii Sweet |

Siebold sedum plant | |

|

Siebold's magnolia or summer magnolia | |

|

= Malus toringo (Siebold) Siebold ex de Vriese |

Toringo apple | in Hortipedia and in Engl. Wikipedia |

| Siebold's crab apple | in Hortipedia | |

|

Siebold's primrose or Siebold's cowslip | |

|

Siebold's cherry | in Hortipedia and externally |

| Knollenziest or Japanese Potato | ||

|

South Japanese hemlock or Araragi hemlock | |

|

Siebold's snowball | in engl. Wikipedia and external (PDF file; 221 kB) |

and a few more.

Honors and memorials

Shortly after his death in 1873, on the occasion of the world exhibition in Vienna, the plan came up to set up a memorial in Siebold's hometown. In Japan, well-known personalities such as Sano Tsunetami , Ōkuma Shigenobu , Terashima Munenori , Kuroda Nagahiro and Siebold's student Itō Keisuke ( 伊藤 圭介 ) called for donations. Of the 865 yen collected, 600 yen were sent to Europe. The remaining 265 yen were used to erect a memorial stone in Nagasaki in 1879. The inscription written by Ōmori Ichū ( 大 森 惟 中 , 1844–1908) in classical Chinese is a song of praise for Siebold's services to Japan. Among other things, it says there:

“Among the scholars of Europe, Siebold is regarded as the scientific discoverer of Japan, and this reputation is well founded. His name is immortal because of his great deed, that he recognized the noblest of our country and people and conveyed the news of it to the nations. "

Three years later Christoph Roth (1840–1907) completed the sculpture for Würzburg. In 1926 the city of Nagasaki placed a bust on the property in Narutaki where Siebold had once instructed his students and treated patients. Busts were also made in the 20th century, for example in Leiden and Tokyo. The overwhelming majority of the busts and illustrations show Siebold in his later years, depictions of the young Siebold from the years of his first stay in Japan are rare.

Munich

The Five Continents Museum in Munich is keeping the collection that Philipp Franz von Siebold put on during his second stay in Japan. Siebold had brought it to Munich in 1866 and exhibited there, in 1874 it was bought by the Bavarian government for what was then Kgl. Ethnographic Museum bought. There is also a letter in the museum from Siebold to King Ludwig I from 1835, in which he encouraged the king to found an ethnographic museum and presented a plan for the establishment and exhibitions.

Philipp Franz von Siebold's grave in the form of a Buddhist stupa is located in the Old South Cemetery . Furthermore, the name of a street in the Upper Au and notes in the botanical garden are reminiscent of the Japanese explorer.

Wurzburg

The Siebold Museum in Würzburg , which was set up in 1995 in the former management villa of Bürgerbräu AG, has a permanent exhibition on exhibits from the Siebold family and from the Japanese researcher's German and Japanese life. There are also special exhibitions that are specially announced. The Siebold company based here is u. a. publishes a newsletter that informs about the activities in the museum and in society. The Siebold-Gymnasium is named after him and his family. Decided in 1873, the inauguration of a Siebold monument, created by Christian Roth on behalf of the Franconian Horticultural Association, located on Geschwister-Scholl-Platz and financed by Austrian, German, Dutch and Japanese donations, took place in 1882.

Bonn

In 2017, a monument with Siebold's bust was unveiled in the Botanical Garden of the University of Bonn.

Suffer

In Leiden , in a house rented by Siebold for his entire life and used as an exhibition space since 2005, under the name “ Siebold House ”, there is a museum dedicated to the relations between Japan and the Netherlands. Several important pieces collected by Siebold are exhibited there. A part of the museum is also dedicated to Siebold himself. The major part of his collection is, however, in the Leiden Reichsmuseum für Völkerkunde . In the Hortus Botanicus of the University of Leiden there are still a dozen trees and bushes imported from Japan by Siebold himself, as well as a bust of the scientist.

Nagasaki

In Nagasaki , on the property near Narutaki , where Siebold trained his students during his first stay in Japan, a Siebold Memorial Museum was built with a permanent exhibition on Siebold's life and work as well as special exhibitions that also cover the wider area. The exhibits also include many objects owned by Siebold's Japanese descendants. The museum publishes an annual scientific bulletin NARUTAKI KIYO and organizes small special exhibitions on selected aspects and people.

Tokyo

In Tokyo , a bust in recognition of his knowledge to his Japanese colleagues were prepared visit to Edo occasion of his.

Fonts

- GT [!] De Siebold: De historia naturalis in Japonia statu, nec non de augmento emolumentisque in decursu perscrutationum exspectandis dissertatio, cui accedunt spicilegia faunae japonicae. Batavia 1824.

- Nippon. Archive describing Japan and its neighboring and protected countries: Jezo with the southern Kuril Islands, Krafto, Kooraï and the Liukiu Islands, edited from Japanese and European writings and own observations. Issued under the protection of His Majesty the King of the Netherlands. Self-published, Leiden / J. Muller, Amsterdam / CC van der Hoek, Leiden 1832 [–1858]. (7 parts).

- Nippon. Archive describing Japan and its neighboring and protected countries Jezo with the southern Kuril Islands, Sakhalin, Korea and the Liukiu Islands. Edited by his sons. 2 volumes. Leo Woerl, Würzburg / Leipzig 1897. (2nd, modified and expanded edition)

- Philipp Franz von Siebold, Joseph Gerhard Zuccarini: Flora Japonica sive Plantae quas in imperio Japanico coll., Descripsit, ex parte in ipsis locis pendingas curavit: [Lugduni Batavorum apud auctorem 1835-1870].

- Philipp Franz von Siebold among others: Bibliotheca japonica, sive Selecta quaedam opera sinico-japonica in usum eorum, qui literis japonicis vacant in lapide exarata a ... Ko Tsching Dschang. Lugduni Batavorum: ex officina editoris, 1833-1841. (Vol. I, "Sin zoo zi lin gjök ben"; Vol. II, "Wa kan won seki. Sio gen zi ko"; Vol. III, "Tsiàn dsü wên"; Vol. IV, "Lui Hŏ"; Vol . V, "Nippon jo tsi ro tei sen tsu"; Vol. VI, "Wa nen kéi")

- Ph. Fr. von Siebold, CJ Temminck, H. Schlegel, WD Haan: Fauna Japonica sive Descriptio animalium, quae in itinere per Japoniam jussu et auspiciis superiorum, qui summum in India Batava Imperium tenent, suspecto, annis 1823-1830 collegit, notis , observationibus, et adumbrationibus illustravit. Lugduni Batavorum, 1833-1850.

literature

- Edgar Franz: German physicians in Japan - a contribution to knowledge transfer in the Edo period . In: Japan Studies - Yearbook of the German Institute for Japanese Studies. Volume 17, Iudicium, Munich 2005, pp. 31-56.

- Edgar Franz: Philipp Franz Von Siebold and Russian Policy and Action on Opening Japan to the West in the Middle of the Nineteenth Century . University of Applied Sciences, Munich 2005.

- Eberhard Friese : Philipp Franz von Siebold as an early exponent of East Asian studies. In: Berlin contributions to social and economic research on Japan. Vol. 15. Bochum 1983, ISBN 3-88339-315-0 .

- Werner E. Gerabek : Siebold, Philipp Franz Balthasar. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 24, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-428-11205-0 , p. 329 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Sybille Girmond: Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold. Doctor, Japanese and natural scientist, ethnologist, botanist and collector . In: Markus Mergenthaler (Ed. On behalf of the Knauf Museum Iphofen): Forays through ancient Japan. Philipp Franz von Siebold, Wilhelm Heine. Röll, Dettelbach 2013, ISBN 978-3-89754-426-0 , pp. 34–51.

- Morinosuke Kajima: History of Japanese Foreign Relations. Volume 1: From the opening of the country to the Meiji restoration . Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1976, ISBN 3-515-02554-5 .

- Toshinori Kanokogi, Gregor Paul (ed.): A contribution to the history of medicine - Philipp Franz von Siebold's diary from 1861. In: Bulleting of the Institute of Constitutional Medicine. Kumamoto University, Vol. 31, No.3, 1981, pp. 297-379.

- Hans Körner: The Würzburger Siebold. A family of scholars from the 18th and 19th centuries (= German Family Archives. A genealogical collection. Volume 34/35). Neustadt an der Aisch 1967 (= sources and contributions to the history of the University of Würzburg. Volume 3), p. 481 ff.

- Josef Kreiner (Ed.): 200 Years Siebold - The Japan Collections Philipp Franz and Heinrich von Siebold. German Institute for Japanese Studies, Tokyo 1996.

- Michael Henker among others: Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796–1866). A Bavarian as a mediator between Japan and Europe (= publications on Bavarian history and culture. Volume 25). 1993, ISBN 3-927233-30-7 .

- Peter Noever (Ed.): The old Japan. Traces and objects of Siebold's journeys. Prestel, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-7913-1850-0 .

- Herbert Plutschow: Philipp Franz von Siebold and the Opening of Japan - A Re-evaluation. Global Oriental, Folkestone / Kent 2007, ISBN 978-1-905246-20-5 .

- Bruno J. Richtsfeld: Philipp Franz von Siebold's Japan Collection in the State Museum of Ethnology in Munich. In: Miscellanea of the Philipp Franz von Siebold Foundation. 12, 1996, pp. 34-54.

- Bruno J. Richtsfeld: Philipp Franz von Siebold's Japan Collection in the State Museum of Ethnology in Munich. In: Josef Kreiner (Ed.): 200 years Siebold. Tokyo 1996, pp. 202-204.

- Bruno J. Richtsfeld: The Siebold Collection in the State Museum of Ethnology, Munich. In: Peter Noever (Ed.): The old Japan. Traces and objects of Siebold's journeys. Munich 1997, p. 209 f.

- Bruno J. Richtsfeld: Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796–1866). Japan researcher, collector and museum theorist . In: From the heart of Japan. Arts and crafts along three rivers in Gifu. Published by the Museum of East Asian Art in Cologne and the State Museum of Ethnology in Munich. Cologne, Munich 2004, pp. 97-102.

- Bruno J. Richtsfeld: Philipp Franz von Siebold as a pioneer of museology according to the written documents in the State Museum of Ethnology in Munich. In: Markus Mergenthaler (Ed. On behalf of the Knauf Museum Iphofen): Forays through ancient Japan. Philipp Franz von Siebold, Wilhelm Heine. Röll, Dettelbach 2013, ISBN 978-3-89754-426-0 , pp. 52-73.

- Alexander v. Siebold: Philipp Franz von Siebold. A biographical sketch . In: Ph. F. v. Siebold: Nippon. Archive describing Japan… . 2 volumes, 2nd, modified and supplemented edition. ed. of his sons. Leo Woerl, Würzburg / Leipzig 1897. Vol. 1, pp. Xiii – xxxiii.

- Juliana von Stockhausen : The man in the crescent moon. From the life of Philipp Franz von Siebold. DVA, Stuttgart 1970, ISBN 3-421-01545-7 .

- Shūzō Kure, Hartmut Walravens (Ed.): Philipp Franz von Siebold. Life and work . (Tokyo 1926) German, significantly enlarged and expanded edition, edited by Friedrich M. Trautz. Iudicium, Munich 1996, ISBN 3-89129-497-2 .

- Markus Mergenthaler: Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold; Doctor, Japan researcher and collector. In Siebolds Netsuke (edited on behalf of the Knauf Museum Iphofen), Dettelbach 2016, ISBN 978-3-89754-486-4 .

- Wolfgang Michel, Torii Yumiko, Kawashima Mabito: Kyūshū no rangaku - ekkyô to kôryû. ( ヴ ォ ル フ ガ ン グ ・ ミ ヒ ェ ル ・ 鳥 井 裕美子 ・ 川 嶌 眞 人 共 編 『九州 の 蘭 学 ー 越境 と 交流』 , Dutch customer in Kyushu - border crossing and exchange). Shibunkaku Shuppan, Kyōto 2009, ISBN 978-4-7842-1410-5 .

- Arnulf Thiede , Alexander Wierlemann, Wolfgang Klein-Langner, Eberhard Deltz: The life and times of Philipp Franz von Siebold . In: Surgery Today. 39 (2009), pp. 275-280, doi : 10.1007 / s00595-008-3888-2

- Andrea Hirner: The blue and the red side of life - What Dr. Philipp Franz von Siebold learned from Master Hokusai . 2013, Kindel eBook. Paperback edition Neopubli Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3737548335 .

- Andrea Hirner, Bruno J. Richtsfeld, Jürgen Betten: Philipp Franz von Siebold and Munich , commemorative publication of the German-Japanese Society in Bavaria eV on the 150th anniversary of death, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-00-052253-6 .

- Andrea Hirner: Philipp Franz von Siebold's Flora Japonica and her Munich artists. Ed .: German-Japanese Society in Bavaria eV, Munich 2020, ISBN 978-3-00-065021-5 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Philipp Franz von Siebold in the catalog of the German National Library

- Author entry and list of the plant names described for Philipp Franz von Siebold at the IPNI

- Siebold Archive of the Ruhr University Bochum

- Siebolds Nippon (PDF, 930 KB) Text excerpts in complete chapters.

- Siebold's Fauna Japonica (pictures), Kyoto University

- Siebold's Flora Japonica (illustrations), Kyoto University

- Siebold's Collection of Japanese Plant Pictures, Kyushu University Museum ( Memento from December 18, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )

- Flora Japonica (text volume 1) , Flora Japonica (text volume 2) and Flora Japonica (table volume) (Latin), as well as Fauna Japonica (French text) at BioLib.

- Siebold's first collection from Japan 1823–1829 (website of the "Sieboldhaus", Siebold's apartment in Leiden, which is now used as a museum)

- Siebold Museum in Würzburg

- Siebold Memorial Museum in Nagasaki ( Memento from March 4, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- Philip Franz von Siebold and Emile Guimet, two Europeans on a journey of discovery to Japan. ( Memento of March 16, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Rencontres , October 15, 2007.

- Philipp Franz von Siebold Prize

- Leo Hoffmann: Philipp Franz von Siebold - founder of Japan research Bavaria 2 radio knowledge . Broadcast on March 9, 2020 (podcast)

- Ingrid Brunner: Philipp Franz von Siebold - Bavarian long nose with a Dutch passport Süddeutsche Zeitung from January 4, 2017 in the series Adventurers from Bavaria

Individual evidence

- ↑ 第 215 回 展示 「慶 應 義 塾 に 見 る シ ー ボ ル ト」 展 ( Memento from September 8, 2012 in the web archive archive.today )

- ↑ Werner E. Gerabek : The Würzburg doctor and natural scientist Philipp Franz von Siebold. The founder of modern research on Japan. In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 14, 1996, pp. 153-160.

- ^ Johann Christiab Stark : Biography of the late Professor DG Chr. Siebold's in Würzburg. In: New archive for obstetrics, women's and children's diseases Jena. Volume 1, No. 1, 1798, pp. 186-196.

- ^ Hans Körner: Die Würzburger Siebold. A family of scholars from the 18th and 19th centuries. Johann Ambrosius Barth, Leipzig 1967 (= portrayals of the life of German naturalists , 13), Neudruck, Degener & Co., Neustadt ad Aisch 1967, pp. 98–112.

- ^ Johann Georg Christoph Siebold: Super recentiorum quorumdam sententia, qua fieri neonati a matribus syphilitici dicuntur [...]. Rienner, Würzburg 1791.

- ↑ Ute Felbor: Racial Biology and Hereditary Science in the Medical Faculty of the University of Würzburg 1937–1945. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1995 (= Würzburg medical historical research. Supplement 3; also dissertation Würzburg 1995), ISBN 3-88479-932-0 , pp. 16-19.

- ^ Bruno Rottenbach: Würzburg street names. Volume 1, Franconian Company Printing Office, Würzburg 1967, p. 83 ( Innerer Graben ).

- ↑ Werner E. Gerabek: The Würzburg doctor and natural scientist Philipp Franz von Siebold. The founder of modern research on Japan. In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 14, 1996, pp. 153-160; here: p. 153.

- ↑ Kösener Corps Lists 1910, 141 , 21

- ↑ Members of the Society of German Natural Scientists and Doctors 1857

- ↑ See Friese (1983).

- ↑ Wolfgang Michel: "The East Indian and neighboring kingdoms, brief explanation of the most distinguished rarities": New finds on the life and work of the Leipzig surgeon and trader Caspar Schamberger (1623–1706). Kyushu University, The Faculty of Languages and Cultures Library, No 1. Fukuoka: Hana-Shoin, 2010, ISBN 978-4-903554-71-6 .

- ↑ Dutch treatises by Siebold's Japanese students シ ー ボ ル ト 門 人 に よ る オ ラ ン ダ 語 論文 ( Memento from October 22, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ ( Page no longer available , search in web archives: Wolfgang Michel: Okudaira Masataka and the Europeans. Nakatsu Sōsho (in Japanese) )

- ^ Philipp Franz von Siebold: Flora Japonica . P. 105, description and illustration

- ^ D. Keene: The Japanese Discovery of Europe, 1720-1830. Stanford University Press, 1969, p. 152.

- ↑ Siebold ²1897, p. Xxv; Noever 1997, p. 12; Kreiner 2006, p. 16.

- ^ Collecting Japan. Philipp Franz von Siebold's vision of the Far East (Museum Five Continents)

- ↑ 1897 in compressed format and reprinted slightly expanded

- ↑ See Franz (2005) and Plutschow (2007)

- ^ Franz (2005), p. 42.

- ↑ See Commodore Matthew Perry .

- ↑ Kajima (1976), Franz (2005), Plutschow (2007)

- ^ The diary for 1861 was published by Kanokogi and G. Paul.

- ↑ Ine, who trained in medicine, made a name for herself as the first female doctor in the country's history.

- ↑ Ōhama & Yoshiwara (eds.): Edo-Tokyō nenpyō . Shogakukan, 1993, ISBN 4-09-387066-7 .

- ↑ Constantin v. Brandenstein: News about the Würzburg Siebold monument. In: Tempora mutantur et nos? Festschrift for Walter M. Brod on his 95th birthday. With contributions from friends, companions and contemporaries. Edited by Andreas Mettenleiter , Akamedon, Pfaffenhofen 2007 (= From Würzburg's City and University History , 2), ISBN 3-940072-01-X , pp. 129–131, here: p. 129

- ↑ Constantin v. Brandenstein: News about the Würzburg Siebold Monument - A list of donations from the 1870s. In: Tempora mutantur et nos? Festschrift for Walter M. Brod on his 95th birthday. With contributions from friends, companions and contemporaries. Edited by Andreas Mettenleiter , Akamedon, Pfaffenhofen 2007 (= From Würzburg's City and University History , 2), ISBN 3-940072-01-X , pp. 129–133

- ↑ http://www.freunde.botgart.uni-bonn.de/wuerzburg.php

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Siebold, Philipp Franz von |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Siebold, Philipp Franz Balthasar von (full name); Siebold, Philipp Franz; Shīboruto-san |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Bavarian doctor, Japanese and natural scientist, ethnologist and plant collector |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 17, 1796 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Wurzburg |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 18, 1866 |

| Place of death | Munich |