Heidingsfeld

|

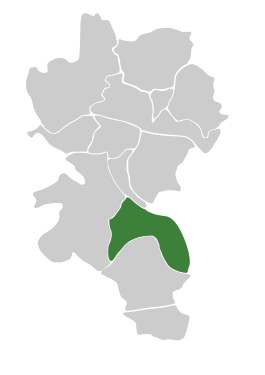

Heidingsfeld district of Würzburg |

|

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 49 ° 45 '46 " N , 9 ° 56' 25" E |

| height | 180 m above sea level NHN |

| surface | 6.90 km² |

| Residents | 10,066 (Dec. 31, 2008) |

| Population density | 1459 inhabitants / km² |

| Incorporation | Jan. 1, 1930 |

| Post Code | 97084 |

| prefix | 0931 |

| Transport links | |

| Federal road |

|

| tram | 3, 5, 504, 505 |

| bus | 16, 31, 33, 34 |

| Source: Würzburg.de | |

Heidingsfeld is a district on the left Main Main and at the same time a district in the south of Würzburg with about 10,200 inhabitants. The former urban area, which existed before the incorporation in 1930, extended from the Steinbachtal to what is now the Heuchelhof district . The locals call their place Hätzfeld in the dialect .

history

Heidingsfeld was mentioned in a document in a market description from 779. Originally, the name should come from "Hedans Feld", the city of the Thuringian Duke Hedan. The place belonged to the Würzburger Mark and has been provable as a royal estate since 849 . Ludwig the German gave the place away to the Fulda monastery , from which it came to the Staufer in the 12th century . In 1297 Heidingsfeld was pledged to the Würzburg monastery by Adolf von Nassau .

In 1273, Bishop Hermann I von Lobdeburg had determined that beguines living in front of the Nikolaustor in Heidingsfeld should found a Benedictine monastery ("Zum Paradies"). In Heidingsfeld on today's Wenzelstrasse, the St. Nikolausspital had existed since the 14th century , a hospital established by Heidingsfeld citizens probably as a foundation for the poor . For the hospital chapel, consecrated to St. Nicholas, the dean of Würzburg Haug Abbey, Conrad Minner, founded a vicarie St. Peter and Paul, confirmed in 1413. In 1516 the hospital was closed. The hospital church was renovated again under Julius Echter. As in neighboring Würzburg and other cities, there were bathing rooms in Heidingsfeld . A bath named “Sygel” for the year 1433 and the bath “Hans Beckman in the blade” one year later are documented.

In 1367 Heidingsfeld was granted city rights. In 1565, Jews expelled from Würzburg settled in Heidingsfeld. Heidingsfeld thus became an important religious center of the Jewish community and was the seat of the chief rabbi of Lower Franconia from the early 18th century until the transfer of the rabbinate to Würzburg in 1814. In the course of this, the Jewish cemetery in Heidingsfeld was inaugurated in 1811 . In the early 19th century, Heidingsfeld had the second largest Jewish community after Fürth in what was then the Kingdom of Bavaria. A Siechenhaus is from about 1321 detected in Heidingsfeld. According to data from the Society for Leprosy in Heidingsfeld, a medieval leprosy can be identified from 1325 .

The Swedes under Gustav Adolf conquered the city in the Thirty Years War .

Heidingsfeld was an independent town from 1367 to 1929 . This is why today's colloquial term "Städtle" (for the Heidingsfelder Altort) is derived, since Heidingsfeld (in 1818 with fewer than 500 families still living there as "City III. Class") represents a small town in the large city of Würzburg. Since 1909 there have been efforts to connect Heidingsfeld to Würzburg. After the Würzburg city council had rejected incorporation with a narrow majority on March 28 and October 28, 1913, Heidingsfeld was replaced on January 1, 1930 under the mayors Hans Löffler (Würzburg) and Max Schnabel (Heidingsfeld) at the request of the citizens after a vote Würzburg incorporated. With this (increased by 5700 inhabitants and 2466 hectares of municipal area) Würzburg became a major city . In 1850 a hospital was built in Heidingsfeld. In 1855 the poor school sisters founded a secondary school for girls and then expanded their care activities in 1857 and 1867 to two further girls' schools and in 1859 to the district orphanage. In 1864 Heidingsfeld received a fire brigade.

In 1892 the Sisters of Mercy founded an urban retirement home in the former Zehnthof of the Würzburg aristocratic secular canon monastery St. Burkard .

The Protestant parish church of St. Paul was built from 1912 to 1913 .

During the Night of the Pogroms in 1938, the synagogue, the central point of reference for the Heidingsfeld Jews, was set on fire at 2:30 a.m. by the National Socialists and destroyed. On March 16, 1945, 85% of the town was badly damaged in the heavy British air raid on Würzburg , including the rectory in which the Heidingsfeld doctor and world-famous Japanese researcher Philipp Franz von Siebold and his mother had lived. On April 2, three days before the surrender of Würzburg, American troops reached Heidingsfeld.

During the term of office of Bishop Matthias Ehrenfried (1924 to 1948) the “Werkinghaus”, supported by the association for charitable and social tasks of the Catholic parish of Heidingsfeld , was set up. It is the first church parish hall in what is now the city of Würzburg.

On July 18, 2016, there was an attack on a regional train near Würzburg , which ended in Heidingsfeld with the shooting of the assassin.

The redesign of the Rathausplatz, which has been planned since 1979/1980, began with the groundbreaking on October 11, 2018 and ended with the handover on October 11, 2018. The redesign introduced a new traffic route and larger areas for pedestrians.

Districts

Old town

The Altort is essentially the area within the city wall and is popularly referred to as "Städtle" (in contrast to the "city", which is commonly referred to as the Würzburg city center).

Mud pit settlement

The clay pit settlement is a housing estate on the slope of the "Blosenberg" northeast of the Würzburg – Lauda-Königshofen railway line . There is hardly any retail trade there, but there are good transport links to downtown Würzburg.

History of origin

In the 1930s, the citizens built the first settler houses with a large garden plot on their own. First of all, the houses were built together by everyone and then raffled off among the future residents. This ensured that no one took advantage of themselves when building the houses. In 1932, with the support of a loan from Bernhard Kupsch , the actual settlement construction with six semi-detached houses began in the Heidingsfeld clay pit . The large gardens of the new settlement, formerly known as the Kupsch settlement, were necessary in order to be able to grow enough food, as many residents were impoverished as a result of the global economic crisis . Under Lord Mayor Theo Memmel , the clay pit settlement was expanded from 1933 to 1936. The non-profit building company , of which the city of Würzburg was the main shareholder, built four houses with 24 small apartments on Lehmgrubenweg in 1934. In 1937 the first " Hitler Youth Home" in Würzburg, conceived as a model project, was built in the clay pit settlement. 1957 was the inauguration of the Catholic parish church of the Holy Family . In the 1960s and 1980s, further building areas were opened up and, since the 1990s, building activities began again.

Katzenberg

The district Katzenberg extends east of the railway line Würzburg - Lauda-Königshofen or southwest of the railway line Würzburg - Ansbach on the slopes of the Katzenberg and Kirchberg. Like the clay pit settlement, Katzenberg is a purely residential area.

Attractions

The Heidingsfeld city wall is almost completely preserved.

The legend of "Giemaul", who is said to have shown the besiegers a secret entrance to the city for money during the siege of the city, is remembered with a grimace on the front of the town hall when it opens its mouth every day at 12 noon, to represent treason. Furthermore, the traitor is said to have tried to have the mayor killed by poison. The Catholic parish church from the 12th century was destroyed in the war, except for the tower. The new building (H. Skull) dates from around 1950. A choir arch crucifix and a mount of olives group from the Riemenschneider workshop are worth mentioning.

In 1987 a Banat Museum of Customs and Costumes was opened in Heidingsfeld .

societies

The “Giemaul” is also remembered in the Giemaul carnival guild, because even at the time of the conquest, many Heidingsfeld citizens were of the opinion that a conquest could not be averted. By opening the gate, "Giemaul" did the city a favor to avoid the destruction by the besiegers.

Sons and daughters of the place

- Paulus I. Zeller († 1563), Abbot of Ebrach Monastery

- Georg Franz Wiesner (1731–1797), Catholic theologian and university professor in Würzburg

- Friedrich Julius Stahl (1802–1861), legal philosopher, lawyer, Prussian crown syndic and politician

- Michael Joseph Rossbach (1842-1894), physician (pathologist, pharmacologist and university professor).

- Max Rosenheim (born June 26, 1849 in Heidingsfeld, † September 5, 1911 in Hampstead, London), wine merchant, important collector of Renaissance medals

- Franz Scheiner (1847–1917), publisher of postcards

- Michael Balling (1866–1925), violist and conductor

- Emil Popp (1897–1955), member of the Reichstag, SS brigade leader, district president in Chemnitz and Köslin

- Hubert Frohmüller (1928–2018), urologist

- Kurt Klühspies (* 1952), handball world champion from 1978

- Dirk Nowitzki (* 1978), basketball player

- Carsten Lichtlein (* 1980), national handball goalkeeper, 2007 world champion

literature

- Rainer Leng (ed.): The history of the city of Heidingsfeld. From the beginning to the present . Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2005, ISBN 3-7954-1629-9 .

Web links

- Photos and information from the Heidingsfeld district

- The place Heidingsfeld - a short description . From: Karl Bosl: Handbook of the historical sites in Germany. Volume 7, Alfred Kröner, Stuttgart.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Erhard Nietzschmann: The free in the country. Former German imperial villages and their coats of arms. Melchior, Wolfenbüttel 2013, ISBN 978-3-944289-16-8 , p. 43.

- ^ Peter Kolb: The hospital and health system. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes, Volume I-III / 2 (I: From the beginnings to the outbreak of the Peasant War. 2001, ISBN 3-8062-1465-4 ; II: From the Peasant War 1525 to the transition to the Kingdom of Bavaria 1814. 2004, ISBN 3 -8062-1477-8 ; III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1478-9 ), Theiss, Stuttgart 2001–2007, Volume 1, 2001, p 386-409 and 647-653, here: pp. 394 and 399 f.

- ^ Sybille Grübel: Timeline of the history of the city from 1814-2006. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes, Volume I-III / 2, Theiss, Stuttgart 2001-2007; III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. Volume 2, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1478-9 , pp. 1225-1247; here: p. 1225.

- ^ Peter Kolb: The hospital and health system. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes, Volume I-III / 2 (I: From the beginnings to the outbreak of the Peasant War. 2001, ISBN 3-8062-1465-4 ; II: From the Peasant War 1525 to the transition to the Kingdom of Bavaria 1814. 2004, ISBN 3 -8062-1477-8 ; III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1478-9 ), Theiss, Stuttgart 2001–2007, Volume 1, 2001, p 386-409 and 647-653, here: p. 398.

- ↑ Medieval Leprosoria in Today's Bavaria, Society for Leprosy, Münster 1995, accessed January 6, 2017 ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Sybille Grübel: Timeline of the history of the city from 1814-2006. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes, Volume I-III / 2, Theiss, Stuttgart 2001-2007; III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. Volume 2, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1478-9 , pp. 1225-1247; here: p. 1226 and 1236.

- ^ Matthias Stickler : New Beginning and Continuity: Würzburg in the Weimar Republic. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. Volume III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1478-9 ), Theiss, Stuttgart 2001-2007, pp. 177-195 and 1268-1271; here: p. 190 f.

- ^ Harm-Hinrich Brandt : Würzburg municipal policy 1869-1918. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes; Volume III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1478-9 ), pp. 64-166 and 1254-1267; here: pp. 157–161.

- ^ Wilhelm Volkert (ed.): Handbook of Bavarian offices, communities and courts 1799–1980 . CH Beck, Munich 1983, ISBN 3-406-09669-7 , p. 597 .

- ^ Horst-Günter Wagner : The urban development of Würzburg 1814-2000. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes, Volume I-III / 2, Theiss, Stuttgart 2001-2007; III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1478-9 , pp. 396-426, here: p. 414.

- ^ Matthias Stickler : New Beginning and Continuity: Würzburg in the Weimar Republic. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. Volume III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1478-9 ), Theiss, Stuttgart 2001-2007, pp. 177-195 and 1268-1271; here: p. 177.

- ^ Sybille Grübel: Timeline of the history of the city from 1814-2006. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes, Volume I-III / 2, Theiss, Stuttgart 2001-2007; III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. Volume 2, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1478-9 , pp. 1225-1247; here: pp. 1228–1230.

- ↑ Alfred Wendehorst: The Benedictine abbey and the aristocratic secular canon monastery St. Burkard in Würzburg. De Gruyter, Berlin 2001, ISBN 978-3-1101-7075-7 .

- ^ Sybille Grübel: Timeline of the history of the city from 1814-2006. 2007, p. 1233.

- ^ Roland Flade: The Würzburg Jews from 1919 to the present. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes, Theiss, Stuttgart 2001–2007, Volume III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1478-9 , pp. 529-545 and 1308, here: pp. 537 and 539.

- ↑ Werner E. Gerabek : The Würzburg doctor and natural scientist Philipp Franz von Siebold. The founder of modern research on Japan. In: Würzburg medical history reports. Volume 14, 1996, pp. 153-160, here: pp. 153 f.

- ↑ Klaus Witt City: church and state in the 20th century. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes, Volume I-III / 2, Theiss, Stuttgart 2001-2007; III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1478-9 , pp. 453–478 and 1304 f., Here: pp. 458–463: The era of the people's and resistance bishop Matthias Ehrenfried (1924–1948). P. 460.

- ↑ Patrick Wötzel: After decades: Groundbreaking at Rathausplatz Heidingsfeld. In: Main-Post. October 11, 2018.

- ↑ Patrick Wötzel: Heidingsfeld: Rathausplatz in the Städtle handed over to the citizens. In: Main-Post. December 11, 2019.

- ^ Sybille Grübel: Timeline of the history of the city from 1814-2006. 2007, p. 1238.

- ↑ Main-Post: Photos are reminiscent of the Kupsch settlement .

- ↑ Peter Weidisch: Würzburg in the "Third Reich". In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes, Volume I-III / 2, Theiss, Stuttgart 2001-2007; III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1478-9 , pp. 196-289 and 1271-1290; here: pp. 246–248 and 251 f.

- ↑ Wolfgang Mainka: Würzburg Gässli and Strässli . 2nd edition 2010, Würzburger Nachtwächter GmbH. ISBN 978-3-00-025890-9 , pp. 59-61.

- ↑ Homepage about the 'Städtle' with a current calendar of events

- ^ Karl Borchardt: Heidingsfeld in Bavarian times until incorporation in 1930. In: Ulrich Wagner (Hrsg.): History of the city of Würzburg. 4 volumes, Volume I-III / 2, Theiss, Stuttgart 2001-2007; III / 1–2: From the transition to Bavaria to the 21st century. Volume 2, 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-1478-9 , p. 1364, note 82.