Bader

Bader , also called Stübner , Latin balneator or female balneatrix ( bath woman ), is an old job title for the operator or employee of a bathing room . The profession has been known since the Middle Ages . On the one hand, Baders were the " doctors of the common people" who could not afford any advice from the trained doctors. On the other hand, they were important helpers of the academically trained medical profession until the 18th century (see Position and Rights ).

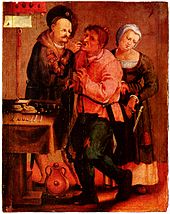

Like the field scissors , they exercised a highly respected, albeit not scientifically accredited, medical profession . It included bathing, body care , cosmetics and sub-areas of surgery , dentistry and ophthalmology, which were still developing . In addition to the bath, a clippers or barber often worked in the bath house , who was responsible for cutting hair and scissors. The craft surgeon , later called surgeon , developed out of these professions, which were sometimes difficult to distinguish .

Position and rights

The social position of the bathers changed over time. Since they touched the sick, wounded and those in need of care, in some places they belonged to the so-called “dishonest” professions that were not allowed to be organized in any guild . In the urban estates of the Middle Ages , children from bathing families were mostly excluded from joining other guilds . It was not until the middle of the 16th century that the imperial laws of 1548 and 1577 gave them the opportunity to learn another craft. The bathing room was generally known as a place of prostitution , which was tolerated by the authorities for sexual chastity despite sometimes eloquent sermons. Cardinals who themselves earned money from prostitution were just as well known as the fact that this human need could not be brought under control with prohibitions. Augustine judged early on: "If you suppress prostitution, reckless lust will spoil society", because it was seen as an outlet for worse escapades from the increasing mass of those who, for reasons of class or guild, had no opportunity to marry.

In some regions and cities, however, they had already been accepted into the guilds, for example in Augsburg and Würzburg in 1373, in Hamburg in 1375, and especially in the southern part of the Holy Roman Empire they became valued members of the bourgeoisie . In Vienna , for example , where the Bader guild can be traced back to the beginning of the 15th century, Baders underwent a craft apprenticeship and formed a stand . In Lübeck, too, the bathing trade was governed by the guild as early as 1350 (Lübecker Baderrolle).

The career path from journeyman to master was explicitly regulated. The apprenticeship with a master lasted three years. Then a three-year wandering and practicing the trade with other masters was required. Only after taking a very expensive master craftsman's examination and an exam at the Vienna Medical Faculty was the Bader allowed to practice independently. In 1548 this professional group received general guild rights in the Holy Roman Empire .

In addition to the few trained doctors, the bathers (or bath women), barbers, clippers, surgeons and midwives made up the majority of healers , especially the poor population in town and country (see also: surgeon ) in the late Middle Ages and early modern times . The Prussian sanitary system developed from the German 'Scherer- und Badertum'.

Since the Council of Tours (1163) forbade clerics to do surgery on the grounds that no clergy could charge "blood guilt" (if the patient had died as a result of the operation), academically trained doctors avoided surgery in the future. Bader, who in addition to the bathhouse, also carried out “minor surgery”, that means, for example, tended small wounds and repaired broken bones, helped to fill the gap in the healthcare system . For example, the bathers were responsible for cutting open and burning out the extremely painful plague bumps .

One of the main tasks of the bathers was the use of bloodletting and cupping . The background to this therapy is the ancient teaching of body fluids . Illness was therefore an outward sign of the disordered body fluids and in particular to be cured by withdrawing blood and restoring the fluid balance. The Bader also extracted teeth and administered enemas . Since the tasks of bathers, surgeons, clippers or barbers overlapped, there were often disputes until the professions were fundamentally separated.

In addition to the clippers or barber and trainees, other historical professions were also part of the other staff in the bathing room. So there was the grinder who dried the bathers and the water extractor who drew the water for the bath from the well. In some places, the Bader had the privilege of keeping donkeys (to transport the water jugs) in the city. The medical assistants were the Lasser (also Lassner, Lässer, Lassmann, Later), who bled the patients, as well as the cupping specialists, whose descendants are called Schrepper (also Schrepfer, Schreppel, Schräpler, Schrepfermann). Bath attendants often helped with the operation of the bathhouse.

In the bathhouse , it was often not just about personal hygiene and hygiene , but also about the pleasure of bathing . Bathhouses were social meeting places. Food was served and stories were exchanged. Sometimes they were matchmakers or brothels , the poor hygienic conditions in some cases led to the spread of sexually transmitted diseases.

In Bavaria there were still bathing schools in the 19th century , including in Würzburg and Landshut . From 1899, for example, these "bathers of the new order" were allowed to work as dentists and to pull teeth.

Further development

After the Thirty Years War (1618–1648), many bathing rooms were closed by ordinance of the sovereigns or cities. As a result, the job profile changed again, as the bathers who continued to work now, like barbers and other professions, carried out their work outdoors or “driving”. With the establishment of hospitals for the poor or even the needy, which began to take off in the 18th century, the importance of the bathers in the field of medicine declined; the scientifically trained university doctors took over an ever larger part of what was previously reserved for bathers. But also village bathers such as Franz Georg Nonnen (Bader in the Rentamt Burghausen von Prutting ) published their knowledge. In Prussia , on the other hand, the medical system was developed from the bathing system and thus professionalized. For this purpose, special training institutions were founded, around 1710 the Charité in Berlin. There were also interrelationships or complementary activities elsewhere. In some communities, the bathhouse and hospital were at times opposite each other in terms of space and division of labor. The profession of bathers was practiced in Germany until the 1950s and was regulated by law. Today, parts of the work spectrum of the former bathers are (co-) taken over by various professions, such as orthopedists , physiotherapists , masseurs , manicures , beauticians or alternative practitioners .

Protection cartridge

The holy twin brothers Cosmas and Damian are, among other things, patron saints of bathers due to their medical profession .

literature

- Erik Hahn: Medical legislation in Saxony. Ärzteblatt Sachsen 2007, ISSN 0938-8478 , pp. 525-527, 569-572.

- Susanne Stolz: The handicrafts of the body. Bader, barber, wig maker, hairdresser. Consequence and expression of historical understanding of the body. Jonas Verlag, Marburg 1992, ISBN 3-89445-133-5 (also: Marburg, Univ., Diss., 1992).

- Birgit Tuchen: Public bath houses in Germany and Switzerland in the Middle Ages and early modern times. Michael-Imhof-Verlag, Petersberg 2003, ISBN 3-935590-72-5 (also: Tübingen, Univ., Diss., 1999).

- Gustav Adolf Wehrli: The bathers, barbers and surgeons in old Zurich. Zurich 1927 (= communications from the Antiquarian Society in Zurich , XXX, 3).

- Martin Widmann, Christoph Mörgeli : Bader and surgeon, medical craft in the past few days. Medical History Institute and Museum of the University of Zurich, Zurich 1998.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Jost Schneider: Social history of reading: on the historical development and social differentiation of literary communication in Germany . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2004, p. 154. ISBN 3-11-017816-8

- ↑ German Encyclopedia or General Real Dictionary of All Arts and Sciences . Volume 18, Varrentrapp and Wenner, Frankfurt am Main 1794, p. 277

- ↑ Stolz, p. 104 ff, p. 108

- ↑ Pride, p. 108

- ↑ Stolz, p. 109

- ^ Ralf Bröer: Medical legislation / medical law. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin and New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , pp. 942-950; here: p. 942 f. ( Health professions ).

- ^ Gertrud Wagner: The trade of bathers and barbers in the German Middle Ages. (Phil. Dissertation Freiburg im Breisgau 1918) Zell i. W. (Buchdruckerei F. Bauer) 1917.

- ^ See also Gustav Adolf Wehrli: Die Wundärzte und Bader as a proper organization. History of the Society for the Black Garden [...]. Zurich 1931 (= notification from the Antiquarian Society in Zurich , XXX, 8).

- ↑ Georges: balneatrix

- ^ The bathing schools in Bavaria (1840)

- ↑ Hans-Carossa-Gymnasium Landshut (2004)

- ↑ Dominik Groß : Between aspiration and reality: The importance of dental treatment measures in the early days of statutory health insurance (1883-1919). In: Würzburger medical history reports 17, 1998, pp. 31–46; here: p. 40.

- ↑ Franz Georg Nonner: The honest village baths or medical-surgical manual for quick and safe use in diseases and emergencies in the country. Johann Michael Daisenberger (Imprimatur: Munich 1791) Stadtamhof 1799