Matteo Ricci

Matteo Ricci (* 6. October 1552 in Macerata , Papal States ; † 11. May 1610 in Beijing , Chinese 利瑪竇 / 利玛窦 , Pinyin Lì Mǎdòu ) was an Italian priest and member of the Jesuit Order , whose missionary work in China during the Ming Dynasty heralded the beginning of the spread of Christianity in China. He is regarded as one of the greatest missionaries in China and is considered to be the founder of the modern China mission.

To commemorate the 400th anniversary of his death, there were numerous publications, symposia and exhibitions about his life and work in 2010.

Historical environment

At the change from the Middle Ages to the modern era, Europeans and Chinese hardly knew anything about each other. From 1405 the emperors of the Ming dynasty equipped several expeditions of the highest court eunuch and admiral Zheng He , who then set sail with 30 ships to explore the coasts of Southeast Asia, India, the Arabian Peninsula and East Africa more closely. When, in the second half of the 15th century, China faced massive attacks by Japanese pirates from the east and the arrival of the less squeamish and uncompromising Portuguese from the west, especially on religious issues, the Ming rulers again acted more cautiously and tried instead, to isolate the country more and more from the rest of the world. The admiral's discoveries were soon forgotten. The Portuguese's monopoly on trade in the Far East was broken in the early 17th century by the Spanish and Dutch, who also landed in China and set up their trading bases here.

In Europe, too, there were few authentic reports about China, and Marco Polo's one seemed too fairy-tale to be true. The prevailing opinion in the scholarly offices was that there were only two large countries at the other end of the world, Cathay and China, which first appeared on a European map in 1575. With the help of their precise measuring instruments, Portuguese explorers who followed the maxim given by Heinrich the Navigator to explore new overseas routes soon reached Asian waters. There they set up their first branches on the coast, initially only in Macau , China , but 30 years later also in Nagasaki, Japan .

Life

The Portuguese navigators and explorers were soon followed by daring clergymen, in particular the missionaries of the Jesuits, the so-called "Society of Jesus", which was founded in 1540 by Ignatius of Loyola . Matteo Ricci also worked in their environment. After his youth in Macerata he was first sent to Rome in 1568 for training and entered the Jesuit order as a novice in 1571 . Whereby he studied law, philosophy, mathematics, astronomy and cosmography. 1572–1577 he worked as a teacher. In March 1578 the gifted young Ricci was sent to the Portuguese city of Coimbra for further studies . From there he traveled to Goa , the administrative seat for Portuguese India , where he went ashore on September 13, 1578 and was supposed to work mainly as a missionary. 1579–1582 he lived in Goa and Cochin .

Ricci later came from Goa to China by ship , which was not without risk at the time because of numerous pirate attacks and hurricanes. Ricci wanted to settle there permanently in order to spread Christianity, since the previous missionary attempts of the Jesuits had failed. In Macau , where he arrived on August 7, 1582, he first made himself thoroughly familiar with the Chinese language , its script and the culture of the Chinese.

In 1583 he settled in Zhaoqing in Guangdong Province together with his brother and compatriot Michele Ruggieri , to whom he had been assigned as an assistant. Both behaved very cleverly and cautiously in their missionary work, adopted local customs, wore the robes of Buddhist monks and were also viewed as such by the Chinese. Since he apparently managed this process of sinization very quickly, he soon found numerous influential friends in the Middle Kingdom. A friar characterized him with the following words:

"Matteo Ricci, Italian, so similar in everything to the Chinese that he seems to be one of them in the beauty of the face and in the delicacy, and in the gentleness and gentleness that they appreciate so much."

From Zhaoqing, Ricci went on to Shaozhou. His goal, however, was to get to the capital Beijing in order to visit Emperor Wanli as the Pope's ambassador and, if possible, to convert him to the Catholic faith on this occasion. The political conditions at the end of the 16th century did not make his project any easier; In 1592 Japan occupied Korea in the Imjin War , whereupon China put its army on the march. Any stranger in China could now be suspected of spying for Japan; the Jesuits were no exception.

After Ricci arrived in the old capital Nanjing in 1595 , he had to turn back before he could settle there permanently in 1598. In 1601 he finally reached Beijing and there soon also the " Forbidden City ", where he was recognized as the ambassador of the Europeans and received at the imperial court. The gifts he carried were accepted as tribute, and Ricci was allowed to settle in the capital. It had taken him nearly 19 years to get into the heart of the empire. Soon other Jesuits from Europe followed him. There is speculation that his math, geography, and astronomy skills even surpassed Chinese scientists. Therefore, the Emperor Wanli later became aware of him and was impressed by the western achievements. Despite his great merits and impeccable reputation, Ricci was never supposed to get to know the emperor personally.

Ricci was buried in the Jesuit cemetery in 1610. The cemetery was devastated during the Boxer Rebellion and the bones from the graves were burned. However, the grave monument Ricci was preserved and is now on the restored and listed building standing Zhalan Cemetery in Beijing.

Research activity

Writer and mathematician

In Zhaoqing, Ricci and Ruggieri tackled extensive translation work, a Portuguese-Chinese glossary; For the first time, Chinese was translated into a European language. From 1588 Ricci was the sole head of the Catholic Mission in China; he succeeded in building long-lasting and close friendships with high-ranking scholars and officials, to whom he owed his extensive knowledge of the teachings of Confucianism. With their support and help, he translated Euclid's elements and commentaries by Christophorus Clavius (1538–1612), who was Ricci's math teacher, into Chinese in 1591 . This was the first detailed written account of occidental mathematics in the Middle Kingdom. This also gave him a great reputation as a mathematician.

In 1594 Ricci wrote his main missionary work, Tiānzhǔ Shíyì ( Chinese 天主 實 義 ), The True Doctrine of the Lord of Heaven , which not only had a decisive influence on the history of missions, but also on the later spiritual exchange between the West and East Asia. In 1595 his most successful book, Jiāoyǒu lùn ( Chinese 交友 論 ) About friendship appeared , which is based on Cicero's De amicitia about the ideal of friendship and ethics. This book is considered by historians to be one of the most widely read Western books in China during the late Ming period.

From 1599 he devoted himself to mathematical, astronomical and geographical tasks. In 1601 in Beijing he developed the theory that Marco Polo's Cathay was identical to China. This could only be confirmed by the land trip of the Jesuit Benedikt Goës (1602-1607). After his death, the Jesuits and some Chinese converts were commissioned to reform the calendar in 1613. This shows that the increasingly stagnant Chinese science has also been overtaken by the Europeans in the field of celestial science.

His extensive report on the China Mission Della Entrata della Compagnia di Giesù e Christianità nella Cina , which he wrote in Italian between 1609 and 1610 in Beijing, was translated into Latin by his friar Nicolas Trigault after his death and was given the title in Augsburg in 1615 De Christiana Expeditione apud Sinas Suscepta from Societate Jesu. Ex P. Matthaei Riccij eiusdem Societatis Commentarijs Libri V. ad SD N published. He had a great influence on the European view of the Chinese Empire.

cartography

Based on the knowledge of the Zheng He's voyages , the Chinese succeeded in drawing up sea charts - such as B. one from the Indian coast - to make. Although these were very detailed and beautifully executed, in return they did not contain any mathematical information.

At the beginning of the 15th century, the Chinese still imagined the world on their maps as follows: The size of the continents is only very imprecise, Europe and Africa are shown much too small, while China and Korea occupy an excessively large place on them. However, the Chinese maps listed numerous city names and important topographical information. Their European counterparts were not as precise, but had degrees of longitude and latitude that made it much easier for seafarers to orientate themselves.

In addition to his other scientific work, Ricci began to work increasingly in the field of cartography, because he wanted to determine the exact coordinates of China. He first consulted Chinese maps and was impressed by the precision and sense of geography of the Chinese cartographers, who checked every detail carefully before writing it on their maps. In addition, he was also active as a land surveyor to determine the latitude and longitude of the cities he visited on his travels. Ricci later continued his work in Beijing to determine the coordinates of the Middle Kingdom. This is how it determined its position in relation to the equator: between 19 and 42 degrees north latitude and between 112 and 131 degrees east longitude. He also made a city map of Nanjing and drew a round map of the world, a kind of prototype, on which all his future work should be based.

World map

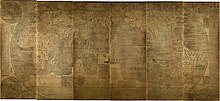

Already at the beginning of his missionary time he found great recognition among the Chinese, because he brought out the first world map on which China, according to their ideas, is shown exactly in the middle of the known world. So far it was also the first of the maps made in China to show the American continent . Since it combined the latest European insights and traditional Chinese knowledge, it was also a novelty in this respect. Ricci's map gave the Chinese for the first time a comprehensive view of the world known at the time. It changed the Chinese view of the world as well as that of the Europeans of China.

Around 1602, with the help of Abraham Ortelius' world map and his own research, he completed the first complete edition of his world map, which was called Kunyu Wanguo Quantu ("Map of the Countless Countries of the World", Latin Magna Mappa Cosmographica or Large World Map of Ten Thousand Countries ) got known. It consists of 6 woodcut prints applied to rice paper and is up to 4 m long and 2 m high. Africa, Europe, America and China are shown in a reasonable size. Ricci put the Chinese empire in the middle of his map - in deliberate contrast to Eurocentric, western cartography - in order to be able to show the emperor the size of his empire, but also its position in relation to the rest of the world more clearly. This "Sinocentric" representation is still used today on the Chinese editions of the world maps.

Ricci's map is also provided with explanations in Chinese characters as well as geographical and ethnological descriptions that provide information about the world known in Europe in the 16th century and also about the Catholic religion. In the text, next to Italy, the Pope is referred to as the “King of Civilization”, and it can also be read here that Europe consists of over 30 kingdoms, all of which had sworn allegiance to the Pope, without the disastrous ones taking place there at the time Wars of religion are mentioned.

The right part of the map shows America, which was completely unknown to the Chinese at the time. For example, Florida is referred to as the "Land of Flowers" on Ricci's map. In the corners of the map there are scientific illustrations with cartographic and astronomical explanations, such as: a. Notes on the equator and the tropics, longitude and latitude, as well as polar projections . The earth is depicted in the center of the universe, corresponding to the Ptolemaic world view of a spherical sky, which was the predominant doctrine for the Catholic Church. For contemporary Chinese astronomers, it was still a square disk.

Missionary activity

Since Ricci spoke fluent Chinese, he was able to convert some high officials of the state and military administration to Christianity in Beijing. So called z. B. a minister named Xu Guangqi徐光启 henceforth Paul Su. His converts supported him particularly in his cartographic and translation work, especially through their contributions from mathematics and Euclidean geometry. Matteo Ricci personally converted only a few people to the Christian faith; but the result of his work is impressive: in 1584 there were three Christians in China, when Ricci's death his order in Beijing had four mission stations and a congregation with around 2,500 members.

rating

Before the term even existed, Matteo Ricci was a cultural mediator between two opposing cultures. He convinced the Chinese through his excellent knowledge of science and his working methods more than through sermons about the Christian religion, which he was originally supposed to spread here. A large mural in the Millennium Monument in Beijing , inaugurated in 2000, shows - in addition to Marco Polo - Matteo Ricci. Today's China thanks him for his contribution to the peaceful rapprochement of two worlds that had barely touched each other until then.

The lunar crater Riccius is named after him and the astronomer Augustine Ricci .

Works (selection)

- Older editions

- The western ars memorativa (Xiguo Jifa). 1596.

- Assured knowledge of God (Tianzhu Shiyi). 1603.

- The twenty-five words . 1605.

- The first six books by Euclid . 1607.

- The ten paradoxes . 1608.

- Newer editions

- Opere storiche . F. Giorgetti, Macerata 1911/13 (2 vol.).

- China in the sixteenth century. The journals of Matthew Ricci [= De Christiana expeditione apud Sinas suscepta ab Societate Jesu]. Random House, New York 1953.

- Douglas Lancashire (Ed.): The true meaning of the Lord of heaven = T'ien-chu shih-i . Institute of Jesuit Sources, St. Louis 1985, ISBN 0-912422-77-7 .

- The forgotten memory. The Jesuit mnemonic treatise "Xiguo jifa" . Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-515-04564-3 .

- Traité de l'amitié . Éditions Noé, Ermenoville 2006, ISBN 2-916312-00-5 .

- Descrizione della Cina , Macerata: Quodlibet, 2011, ISBN 978-88-7462-327-3 .

See also

literature

German

- Herbert Butz, Renato Cristin: Philosophy and Spirituality with Matteo Ricci . Edition Parerga, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-937262-67-3 .

- Vincent Cronin : The Jesuit as Mandarin ("The Wise Man from the West. Matteo Ricci and his Mission to China"). Goverts Verlag, Stuttgart 1959.

- Walter Demel: Matteo Ricci. In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 8, Bautz, Herzberg 1994, ISBN 3-88309-053-0 , Sp. 181-185.

- Jacques Gernet : Christ came to China. A first encounter and their failure (“Chine et Christianisme”). Artemis, Zurich 1984, ISBN 3-7608-0626-0 (translated by Christine Mäder-Virágh).

- Gisela Gottschalk : China's great emperor. Their history, their culture, their achievements . Weltbild, Augsburg 1992, ISBN 3-89350-354-4 .

- Rita Haub , Paul Oberholzer: Matteo Ricci and the Emperor of China. Jesuit mission in the Middle Kingdom . Echter-Verlag, Würzburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-429-03226-5 .

- Johann Hoffmann-Herreros: Matteo Ricci. The Chinese are Chinese; a missionary seeks new ways . Matthias Grünewald Verlag, Mainz 1990, ISBN 3-7867-1512-2 .

- Nina Jocher: About friendship (Dell 'amicizia). Quodlibet, Macerata 2005, ISBN 978-88-7462-047-0 .

- Michael Lackner (ed.): The forgotten memory. The Jesuit Mnemonic Treatises . Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-515-04564-3 .

- Werner Stürmer: The Wise Man from Far West (Matteo Ricci). St. Benno-Verlag , Leipzig 1983.

- Sven Trakulhun: Culture change through adaptation? Matteo Ricci and the Jesuit Mission in China . In zeitenblicke 11/1 (2012), http://www.zeitenblicke.de/2012/1/Trakulhun (accessed on September 12, 2013).

- Li Wenchao: The Christian China Mission in the 17th Century. Understanding, incomprehension, misunderstanding (Studia Leibnitiana: Supplementa; Vol. 32). Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-515-07452-X (plus habilitation thesis, FU Berlin 1996).

English

- Jonathan Spence : The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci . Faber Press, London 1986, ISBN 0-571-13239-1 .

- Kim Sangkeun: Strange Names of God. The missionary translation of the divine name and the chinese response to Matteo Ricci's Shangti in Late Ming China, 1583-1644 . Lang Press, New York 2004, ISBN 0-8204-7130-5 (also dissertation, Princeton University 2001).

- Louis J. Gallagher (Ed.): China in the 16th Century: The Journals of Matthew Ricci: 1583 - 1610 . (Translated from the Latin by Louis J. Gallagher) New York: Random House 1953.

French

- Jacques Bésineau: Matteo Ricci. Serviteur du maître du ciel . Desclée de Brouwer, Paris 2003, ISBN 2-220-05257-5 .

- Vincent Cronin: Matteo Ricci, le sage venu de l'Occident . Editions Albin Michel, Paris 2010.

- Paul Dreyfus: Mattèo Ricci. Le jésuite qui voulait convertir la Chine . Édition du Jubilé-Asie, Paris 2004, ISBN 2-86679-380-3 .

- Jean-Claude Martzloff : De Matteo Ricci a l'histoire des mathématiques en Chine . In: Bulletin de la Société Franco-Japonaise des Sciences Pures et Appliquées , Vol. 42 (1986), pp. 6-19.

- Michel Masson: Matteo Ricci. Un jesuite en Chine; Les savoirs en partage au XVII siecle, avec bait lettres de Matteo Ricci . Edition Facultés Jésuites de Paris, Paris 2009, ISBN 978-2-84847-022-1 .

- Vito Avarello: L'oeuvre italienne de Matteo Ricci: anatomie d'une rencontre chinoise. Paris, Classiques Garnier, 2014, 738p. ISBN 978-2-8124-3107-4 .

Italian

- Michela Fontana: Matteo Ricci. Un gesuita alla corte dei Ming . Mondadori, Milano 2005, ISBN 88-04-53953-4 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Matteo Ricci in the catalog of the German National Library

- Publications by and about Matteo Ricci in VD 17 .

- Matteo Ricci, border crosser between cultures

- Music of the time of Matteo Ricci

- Andrea Kath: October 6th, 1552 - Birthday of the Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci WDR ZeitZeichen (podcast).

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i François Angelier: Dictionnaire des Voyageurs et Explorateurs occidentaux du XIIIe au XXe siècle. Pygmalion (Éditions Flammarion), Paris 2011, ISBN 978-2-7564-0156-0 , p. 587 f .

- ↑ Wolfgang Franke: China and the West . Göttingen 1962, p. 21.

- ↑ Gianni Criveller. A Reflection on Zhalan, a cemetery in Beijing where illustrious Italians rest. Retrieved February 15

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Ricci, Matteo |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Italian Jesuit and China missionary |

| DATE OF BIRTH | October 6, 1552 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Macerata , Papal States |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 11, 1610 |

| Place of death | Beijing , China |