Japanese color woodcut

The Japanese color woodcut is a specific type of printmaking that originated in Japan in the second half of the 18th century and whose traditions, with few exceptions, are continued uninterruptedly by Japanese artists.

Stylistic devices

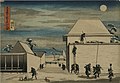

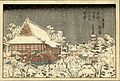

The lack of light and shadow effects is characteristic of the classic Japanese color woodcut. Objects and people are drawn with clear, flowing lines, areas are filled with color or left blank and shapes are often stylized. As in all classical Chinese and Japanese painting , the aim of the representation is not the lifelike reproduction of a subject , but the representation of its essence, its character. The artist only suggests that the picture itself is only composed in the mind of the beholder.

Another characteristic of the color woodcuts (and the painting) is the lack of perspective or the lack of a clear center of the picture. The illusion of spatial depth is achieved by overlapping objects reaching out of the picture and by scenes placed side by side or behind one another.

Japanese artists had known the western perspective representation at least since the middle of the first half of the 18th century. However, this technology was only used in certain contexts, e.g. B. to create the impression of strangeness or to depict the strangeness itself - or, as in the case of the Chūshingura depictions, to relocate the state-forbidden representation of real circumstances that had occurred after 1500 to an apparently distant and alien world rapture.

history

The technique of woodcut has been proven in Japan since the 8th century, as evidenced by texts with depictions of deities. Representations remained limited to religious subjects until the 15th century, and letterpress printing was the monopoly of shrine and temple printers.

The first commercial publishers emerged around 1600 in Kyoto , from 1670 in Osaka and from 1730 in Edo (today's Tokyo ), where the focus from the beginning was on entertainment literature with a high proportion of illustrations. The first individual print images appeared in the second half of the 17th century: initially simple black and white images, then around 1700 the first prints hand-colored with one or a maximum of two colors. Prints with three printing plates (black, pink, green) were found from 1740, and true multi-color printing was in use from around 1765. From then on, the prints were called Nishiki-e ( Japanese錦 絵, brocade pictures ).

Even after the end of the Edo period in 1865, several million woodblock prints were printed. They enjoyed great popularity among the urban upper class and petty bourgeoisie as well as with simple craftsmen, merchants and lower workers. The immense success of the colored woodcuts was based on the fact that they expressed the lifestyle and the experience of the urban population by adopting the style and content of ukiyo-e painting and making them accessible to a wide audience. While paintings were unaffordable and inaccessible for most of the population, as they often cost an annual income, a normal color woodcut was available for the price of a simple meal.

The publishers and artists of the woodblock prints were subject to constant restrictions by state censorship. This concerned the subjects depicted, names of actors or courtesans, restrictions in printing technology, temporary prohibition of all kabuki prints, etc. Violations of these prohibitions were sometimes severely punished, but the official censors were often not too strict about enforcing the state requirements . However, the ban on portraying members of the ruling Tokugawa family and portraying or commenting on real political situations that occurred after 1500 was strictly monitored and sanctioned . This ban was only circumvented immediately before the end of the Tokugawa government.

Utagawa Yoshitora , 1862

Edo was the center of the production of colored woodblock prints. From there, they were brought back as souvenirs or sold by traveling vendors and spread throughout the country. Stars of kabuki theater, brothel women and successful sumo wrestlers had admirers all over Japan.

The second center of production was Osaka, where a population structure similar to that in Edo had developed. Osaka prints were more stylized than Edo prints and were characterized by their better print quality on average.

Prints from Nagasaki , brought along as souvenirs, were supposed to show friends and acquaintances the life of the Dutch and Chinese who frequented there. Similar prints, albeit of poorer quality, were made in Yokohama with the opening of Japan from around 1860 to depict the lives of the Americans and Europeans living there.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, it has been customary in Japan to refer to all woodcuts and colored woodcuts that have appeared up to then as Ukiyo-e hanga (prints of images of the flowing world). However, for some prints, notably Kacho-e and Meisho-e , and artists like Katsushika Hokusai and the artists of the Meiji period , this should be looked at in a more nuanced way.

From 1900 onwards, new forms of Japanese color woodblock print, the Shin hanga and the Sōsaku hanga, emerged .

Manufacturing process

material

For the printing, wooden panels that were sawn to size and carefully smoothed were used, mostly from the wood of the wild cherry tree. Pressure plates made from the wood of the trumpet and book trees were also used occasionally.

The printing was done on Japanese paper made from various types of plants. Most commonly use therein found the from the bast of the mulberry tree produced Kozo-gami . This paper was available in different qualities from very thin and almost transparent to relatively thick and creamy white. What all paper types have in common is their high tear resistance, elasticity and absorbency.

The colors were produced on a vegetable and mineral basis until around 1860. They are characterized by high brilliance, but have the disadvantage that they fade or become oxidized under the influence of light and / or moisture (in particular orange tones made from mercury compounds that turn dark brown). The only non-fading color was black, which was obtained as an ink from charred blocks of wood or tree resin.

From 1820 onwards, the first artificially produced color Prussian blue was known in Japan , which, due to its luminosity, was increasingly used for printing color woodblock prints from around 1830 onwards.

In 1860, aniline dyes were introduced to Japan, which increasingly replaced the traditional colors in woodblock prints. Many so-called Meiji prints are characterized by the intensive use of red tones.

Employee

A finished woodblock print was produced in several steps. Four people were always involved in the production of a classic Japanese woodcut:

- The publisher

- He commissioned an artist for a theme or motif, ensured the financing of the raw materials (printing plates, paper and inks), coordinated the work of the people involved and was responsible for distribution and sales.

- The artist

- He provided ideas for the design of the theme or motif, possibly made several drafts and then drew the specified draft with ink and brush on thin paper. Details of the image background, clothing and other items could also be added by his students or experienced copyists. The finished design was then converted into a final drawing that was given to the woodcutters as a template.

- The wood cutters

- First a printing plate was made that only contained the contours of the print that would later appear in black. Different wood cutters shared the work. Some were responsible for the rough contours of the buildings, plants and garments, and the person primarily responsible, who was the only one authorized to sign on the print, made the up to a tenth of a millimeter thin lines of the faces, hairstyles and hands.

- The printer

- He initially received the finished contour block, from which he initially only made “black prints”. The artist then drew the outlines and details of the colored areas on these, using a separate print for each color tone. Using these specifications, the wood cutters produced the color printing plates and, if necessary, other plates for special effects such as blind or mica printing. Now the printer finished the full prints. To do this, he had to take great care so that the registration marks of the printing plates matched within a fraction of a millimeter.

Under certain circumstances, the finished prints were subjected to a post-treatment, such as. B. polishing individual color areas. After the Tenpo reforms in 1842, the number of color plates was limited to eight. Before that, ten to twenty printing plates were quite common; the record in 1841 is said to have been 78 plates used for a single print.

Publication way

Color woodblock prints very often appeared as single sheet prints , which are called Ichimai-e regardless of format . This includes all single sheets published for commercial purposes, multi-sheet prints (diptych, triptych etc.), all series and fan prints.

The Ichimai-e do not include the privately published surimono : greeting cards that were given away to friends and acquaintances on various occasions such as New Year or to announce and invite private music and dance events, and which are also available as single sheets, in series and in Multiple prints were produced. They are often characterized by an above-average print quality.

Color woodblock prints (and black and white woodblock prints) were also produced as book illustrations.

Formats

In addition to many other paper formats, the vertical Ōban format was the most common (approx. 24 × 36 cm) for multi- color printing , and the Chūban format (approx. 18 × 27 cm) was also quite common .

For surimono , which initially appeared in different formats, the shikishiban format was used almost exclusively from around 1810 (around 18 × 18 cm).

subjects

Subjects of the individual prints (some with details of special subjects):

- Kabuki-e: Scenes from the plays of popular Japanese kabuki theater

- Yakusha-e: portraits of Kabuki actors in special roles, but also in their free time

- Shini-e: memory images of deceased actors, but also of other personalities

- Bijin-ga : portraits of beautiful women, courtesans, geisha and prostitutes

- Sumo-e: portraits of sumo wrestlers, depictions of famous fights and important tournaments

- Musha-e: Images of warriors, famous battles of the past and portraits of important figures in Chinese and Japanese history

- Chūshingura-e: Description of the vengeance campaign of the 47 abandoned samurai

- Meisho-e: pictures of famous places, landscapes

- Tōkaidō-e: Representation of the stations on the Tōkai trade route between Edo and Kyōto

- Kacho-e: pictures of nature, representation of plants and animals

- Genji-e (approx. From 1840): Scenes from the classic novel Genji Monogatari , in order to be able to depict the life of the rich and beautiful while circumventing the censorship regulations

There were also joke pictures, devotional pictures, board games and accessories, picture prints for children, fairy tale and legend pictures and pictures of the protective and lucky deities.

The subjects of the illustrated books also included the directions listed above. Most of the book publications, however, have been illustrated contemporary popular novels and short stories. An important branch of book production was the Shunga ( spring pictures, erotic drawings with often revealing depictions), the sale of which was officially prohibited, but which nevertheless enjoyed strong demand.

Book dismantling in the west

The numerous illustrated books of the late Edo period were and are often dismantled in the West in order to sell the pages individually. Many, if not most, of the black and white prints and Japanese woodblock prints in smaller formats were originally part of a book.

The Japanese color woodcut in Europe

The French painter and graphic artist Felix Bracquemond boasted that he was the first to discover Japanese woodblock prints in Europe in 1856 - in the form of crumpled packaging material in boxes of art objects. In fact, however, the first Japanese woodcuts and printed books came to Europe as early as the end of the 17th century via the Dutch trading post Deshima , located outside Nagasaki , and by the end of the 18th century individual prints and illustrated books could be found in museums in London, Paris and Stockholm.

The German doctor Philipp Franz von Siebold brought an extensive collection of Japanese woodblock prints and books to Leiden in the Netherlands in 1830, some of which were on public display from 1837. These exhibits went unnoticed by the public, as did the colored woodcuts brought back from Japan as souvenirs by American, English and French sailors from 1853 onwards.

It was not until the two world exhibitions in London in 1862 and in Paris in 1867, at which current woodblock prints were presented alongside other products from Japanese handicrafts, that art lovers became aware of the appeal of Japanese products. Artists, critics and collectors are deeply impressed by the quality of the craftsmanship and the artistic expressiveness of the exotic Far Eastern works.

When Japanese handicrafts such as metal, lacquer and bamboo work from around 1870 onwards led to a wave of Japonism , especially in Parisian salons, Japanese woodblock prints began to be collected. Bracquemond and the Goncourt brothers were the first important collectors of Japanese woodblock prints in Paris, and imitators soon found themselves, including the painters Édouard Manet , Claude Monet , Edgar Degas and Vincent van Gogh as well as the writers Charles Baudelaire and Émile Zola . The passion for collecting was soon served by specialized dealers such as Siegfried Bing (1838–1905) or Tadamasa Hayashi (1853–1906).

Influence on European art

The influence of Japanese woodcuts on Vincent van Gogh is evident and evident . At first he tried his hand at japonized images, such as B. his well-known iron geisha or two oil paintings based on motifs by Utagawa Hiroshige . Then he consistently implemented the essential elements of the Japanese color woodcut (clear lines, stylized forms and colored areas) in the technique of western oil painting. Other congenial artists such as Paul Gauguin and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec took up aspects of this technique in their painting. Among other things, Edvard Munch also created woodblock prints by Japanese models.

Art Nouveau poster painting , the painting of the Vienna Secession and many expressionists such as James Ensor , Paula Modersohn-Becker , Marianne von Werefkin and Alexej Jawlensky were also influenced by stylistic elements of the Japanese color woodcut.

Masters of the classic Japanese woodblock print (selection)

|

|

Shin hanga

At the beginning of the 20th century, artists were growing tired of the highly formalized depictions of ukiyo-e. At the same time, more and more European influences came to Japan, especially Impressionism had a strong impact on Japanese artists. The stylistic language of the classic Japanese woodcut was basically retained, but people were now depicted more individually and played with light and shadow. Such images are known as shin hanga ( new prints ).

The publisher Shōzaburō Watanabe (1885–1962), who had numerous artists work for himself and also pursued export intentions, played a major role in the spread of the new art direction . Outside of Japan, a market for shin-hanga graphics developed, particularly in the United States, especially when American occupation soldiers brought the images back home with them after World War II. This is how some large shin hanga collections came into being in the USA.

Masters of Shin Hanga Woodblock Prints (selection)

- Shinsui Itō (1898–1972)

- Hasui Kawase (1883–1957)

- Hiroshi Yoshida (1876–1950)

- Shikō Munakata (1903-1975)

See also

List of technical terms used in Japanese woodblock prints

Katsukawa School

Utagawa School

Block Printing

literature

For beginners and those interested:

- Ellis Tinios: Japanese Prints . London, 2010, ISBN 978-0-7141-2453-7 (English).

Technical literature:

- Julius Kurth : History of the Japanese woodcut . 3 volumes, Leipzig, 1925–1929.

- Richard Lane: Images from the Floating World . Friborg, 1978, ISBN 0-88168-889-4 (English).

- Friedrich B. Schwan: Handbook of Japanese woodcut . Munich, 2003, ISBN 3-8912-9749-1 .

- Amy Reigle Newland (Ed.): The Hotei Encyclopedia of Japanese Woodblock Prints . 2 volumes, Amsterdam, 2005, ISBN 90-74822-65-7 (English).

- Andreas Marks: Japanese Woodblock Prints. Artists, Publishers and Masterworks 1680-1900 . North-Clarendon, 2010, ISBN 978-4-8053-1055-7 (English).

- Hendrick Lühl: The treasures of the Kamigata. Japanese woodblock prints from Osaka 1780–1880 . Nünnerich-Asmus Verlag, Mainz 2012, ISBN 978-3-943904-16-1 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Marianne Werefkin , Munich 2001, p. 133 ff.

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Jawlensky and his companions in a new light , Munich 2004, pp. 127–138

Web links

- Viewing Japanese Prints (English)

- A Guide to the Ukiyo-e sites of the Internet (English)

- Japanese Woodblock Print Search (English)