Marianne von Werefkin

Marianne von Werefkin ( Russian Марианна Владимировна Верёвкина / Marianna Vladimirovna Werjowkina , scientific. Transliteration Marianna Vladimirovna Verevkina ; born August 29 . Jul / 10. September 1860 greg. In Tula , Russian Empire ; † 6 February 1938 in Ascona , Switzerland ) was a Russian painter who did outstanding work for German Expressionism .

Life

In Russia 1860–1896

Marianna Wladimirowna Werjowkina was born as the daughter of Elisabeth, b. Daragan (1834–1885), and Wladimir Nikolajewitsch Werjowkin (1821–1896), the commander of the Ekaterinburg regiment in Tula, the capital of the Russian governorate of the same name. The father was a Russian nobleman whose ancestors came from Moscow . He made a career in the military, became a general and most recently in command of the Peter and Paul Fortress in Saint Petersburg . The mother belonged to an old Cossack princely family . She was a painter who had learned icon painting from Carl Timoleon von Neff .

Werefkin's talent for drawing was discovered in 1874. She immediately received academic drawing lessons. As a teenager, she had a large studio in the Peter and Paul Fortress and a studio house on her family's estate called “Blagodat” (Bliss) in Lithuania . It is located about 7 kilometers northwest of the provincial town of Utena in the Vyžuonėlės Park, which was declared a Lithuanian natural monument in 1958. Werefkin regarded the estate and the landscape there as her real home.

In 1880 she became a private student of Ilya Repin , the most important representative of the Peredwischniki ("traveling painters"), who represented Russian realism . Through Repin, Werefkin got in touch early on with the artist colony of Abramzewo and with Valentin Alexandrowitsch Serow , Repin's second private student. In Moscow since 1883, she studied painting with Illarion Mikhailovich Prjanischnikow and attended lectures by Vladimir Sergeyevich Solovyov . In 1888 Repin created the portrait of Marianne Werefkin , in the same year she suffered a hunting accident in which she accidentally shot her right hand, the painter's hand.

Werefkin's first, artistically important work phase is the time before 1890, when she made a name for herself in realistic painting of the tsarist empire as "Russian Rembrandt". Some works have been preserved, others can only be proven through photos, many have been lost. After 1890, Werefkin modernized her painting style and switched to open-air painting with features of impressionism with Eastern European characteristics. Apparently only two paintings still exist from this period.

In 1892 Werefkin entered into a 27-year relationship with Alexej Jawlensky . She was more advanced in painting than he was and had decided to train and promote the penniless officer, who was five years her junior.

In Germany 1896–1914

In 1896, after the death of her father with a noble tsarist pension, Werefkin moved to Munich with Jawlensky and her maid Helene Nesnakomoff . She rented a comfortable double apartment in the Schwabing district , which she furnished partly with furniture in Empire style and Biedermeier style , which she contrasted with folk art furniture that was made in the workshops of the artist Jelena Dmitrijewna Polenowna (1850–1898) in the Abramzewo artists' colony were. She initially entrusted Jawlensky's further training to the Slovenian Anton Ažbe , while she interrupted her own painting for exactly ten years in order to benefit from his training. Like many women in art , she subordinated her artistic ambitions to the interests of her lover.

Werefkin knew that Jawlensky was a philanderer: "Love is a dangerous thing, especially in the hands of Jawlensky." She refused a marriage, not least because of the tsar's generous pension, which she would have lost as a married woman. But she had made it into her head to promote him as an artist in every way. In her place he was supposed to achieve and realize artistically everything that a “weak woman” was denied anyway.

“Three years passed in tireless care of his mind and heart. I pretended to take everything, everything that he received from me - I pretended to receive everything that I put into him as a gift ... so that he shouldn't be jealous as an artist, I hid my art from him "( Werefkin, quoted in Fäthke 1980: 17). Jawlensky thanked her by assaulting nine-year-old Helene Nesnakomoff, Werefkin's maid's assistant, with whom he already had a relationship.

In 1897, Werefkin founded the brotherhood of Saint Luke in their “pink salon” , whose members understood themselves in the tradition of the Lukasgilde and which was ultimately the nucleus of the New Munich Artists' Association (NKVM) and the Blue Rider .

In 1897 she was in Venice with Ažbe, Jawlensky, Dmitry Kardovsky and Igor Emmanuilowitsch Grabar , initially to visit a Repin exhibition. They then studied painting by old masters in various Upper Italian museums.

In 1902 the maid Helene von Jawlensky had a child, Andreas Nesnakomoff († 1984). In November 1902 Werefkin began to write her Lettres à un Inconnu (letters to a stranger) as a kind of diary, which she finished in 1906. A year later she went to Normandy with the Russian painter Alexander von Salzmann , while Jawlensky stayed in Munich.

In 1906 Werefkin traveled to France with Jawlensky, Helene and their son Andreas. First they went to Brittany . From there it went via Paris and Arles to Sausset-les-Pins near Marseille , where her painter friend Pierre-Paul Girieud (1876–1948) lived. There on the Mediterranean Sea, Werefkin resumed her artistic activity.

Her first expressionist paintings were created in 1907 . Stylistically, she followed the theories of Vincent van Gogh , the surface painting of Paul Gauguin , the tone-on-tone painting of Louis Anquetin , the caricatural and striking painting of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and the ideas of the Nabis . In the Friends of Munich she was nicknamed "The French Woman". In terms of iconology and motifs, Werefkin often leaned on works by Edvard Munch , and she brought the artists mentioned back into the picture before her colleagues, such as Wassily Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter , took the first step into Expressionism. Back then, the artists Jan Verkade , Hugo Troendle and Curt Herrmann frequented their salon.

In the spring of 1908 Gauguin's Polish friend, Władysław Ślewiński , visited Werefkin. He convinced Jawlensky to use surface painting. In the summer, the two artist couples Werefkin / Jawlensky and Münter / Kandinsky met to paint together in Murnau am Staffelsee in Upper Bavaria . In the winter of the same year Werefkin, Jawlensky, Adolf Erbslöh and Oscar Wittenstein had the idea of founding the NKVM, of which Kandinsky was appointed first chairman in 1909. The dancer Alexander Sacharoff became a member of the NKVM With Werefkin and Jawlensky he prepared his big performance at the Odeon in Munich.

In 1909, the Swiss painter Cuno Amiet , who was then a member of the Brücke artists' association , was a guest in Werefkin's salon. Later he would become one of their best Swiss friends alongside Paul Klee and his wife Lily . On December 1, 1909, the opening of the first exhibition of the NKVM with 16 artists took place. Werefkin exhibited six paintings, including Schuhplattler , her commitment to Bavarian folk art. The painting Twins was also created in 1909 .

Shortly afterwards Werefkin went to Russian Lithuania to her brother Peter (1861-1946), who was governor in Kaunas . Many drawings and many paintings were created there that winter.

At the end of September 1910, Franz Marc contacted the artists of the NKVM. We learn from himself that it was primarily Werefkin and Jawlensky who opened his eyes to a new art.

From the beginning of May 1911, Pierre Girieud (1875–1940) lived with Werefkin and Jawlensky in Giselastraße, when he and Marc showed his paintings in an exhibition at the Modern Gallery Heinrich Thannhauser . In the summer, Werefkin traveled with Jawlensky to Prerow on the Baltic Sea . At the end of the year they went to Paris, where they met Henri Matisse personally.

Kandinky left the NKVM together with Münter and Marc in December 1911 in order to present the first exhibition of the Der Blaue Reiter editorial team in the winter of 1911/1912 . In 1912, Werefkin and Jawlensky also left the association, which Erbslöh officially took out of the Munich register of associations in 1920. Werefkin also exhibited with the members of the NKVM and the Blauer Reiter together with the artists of the Brücke from November 18, 1911 to January 31, 1912 in the New Secession in Berlin. There she showed her painting Skaters .

In 1913, Werefkin and Jawlensky took part in the exhibition of the Der Blaue Reiter editorial team in the Berlin gallery Der Sturm by Herwarth Walden . In the same year Werefkin intended the final separation from Jawlensky and traveled to Vilnius in Lithuania, where her brother Peter had meanwhile become governor. At the end of July 1914, Werefkin returned to Germany from Lithuania. She arrived in Munich on July 26th.

In Switzerland 1914–1938

When the First World War broke out on August 1, 1914, Werefkin and Jawlensky had to leave Germany within 24 hours and fled to Switzerland with the service staff Maria and Helene Nesnakomoff and their son Andreas. At first they lived in Saint-Prex on Lake Geneva . As a result of the war, Werefkin's pension was cut in half. In 1916 a solo exhibition took place in Zurich , where the couple moved in September / October 1917.

As a result of the Russian October Revolution , Werefkin lost her tsarist pension. This was followed by a participation in Cabaret Voltaire after Werefkin had met its initiators. In 1918 Werefkin and Jawlensky moved to Ascona on Lake Maggiore . In 1919 Werefkin was involved in an exhibition “Painters from Ascona” at the Wolfsberg art salon in Zurich, together with Jawlensky, Robert Genin , Arthur Segal and Otto Niemeyer-Holstein . In 1920 some of her works were shown at the Venice Biennale . Werefkin has always lived as a stateless person in Switzerland , and has had a Nansen passport since 1922 .

In 1921 Jawlensky separated from Werefkin and moved to Wiesbaden , where he married Werefkin's housekeeper Helene, the mother of his son Andreas, in 1922. During this difficult time, she made friends with the Zurich painter Willy Fries and his wife Katharina born. Righini (1894-1973). In 12 letters to Zurich between 1921 and 1925 she described her desperate situation, which could not break her courage and her workforce.

In 1924 Werefkin co-founded the artist group Der Große Bär in Ascona together with Walter Helbig , Ernst Frick , Albert Kohler and others. This group of artists had a major exhibition in the Bern art gallery in 1925 , followed by other joint exhibitions, including 1928 in the Berlin gallery Nierendorf together with Christian Rohlfs , Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Robert Genin .

Again and again she earned her living by painting posters and picture postcards or she wrote articles, for example in 1925 for the Neue Zürcher Zeitung , in which her impressions of a trip with Ernst Alfred Aye to Italy were printed.

In 1928 Werefkin wrote and painted her Ascona impressions, which she dedicated to the Zurich art critic Hans Trog (1864–1928). In the same year she met Diego Hagmann (1894–1986) and his wife Carmen (1905–2001), who saved them from major economic hardship.

In the last two years before the First World War in Munich, stylistic changes in Werefkin's pictures that lead into her older work had already made themselves felt, so she developed them further in Switzerland. Her paintings no longer triggered sudden "shocks" in the same way as before. Her works became generally more narrative, more internalized and even more profound than before. In particular, they attracted writers and inspired them to interpret and create their own, such as the poet Yvan Goll or the poet Bruno Goetz .

The typically Russian features in Werefkin's painting, especially in the coloring, which the poet Else Lasker-Schüler in Munich had already noticed, should appear particularly clearly in her late work in Ascona. Even if she transferred them to Ticino motifs, Werefkin's pictures were initially foreign to most Swiss people and were often misunderstood.

When Werefkin died in Ascona on February 6, 1938, she was buried in the local cemetery according to the Russian Orthodox rite, with the participation of almost the entire population.

A large part of her painterly and literary estate is kept in the Fondazione Marianne Werefkin in Ascona. Thanks to donations, their holdings have now grown to almost 100 paintings. She also owns 170 sketchbooks and hundreds of drawings. Part of it is presented in the permanent collection of the Museo communale d'arte moderna in Ascona.

Werefkin and Japonism

In addition to the models of van Gogh , Gauguin and the Nabis , Japanese art played an important role for Werefkin well into old age. Her interest in this was evidently aroused in Russia by one of her great role models, namely James Abbott McNeill Whistler , "the first Japonist" .

In addition to Japanese woodcuts , Werefkin's estate also contained literary evidence that demonstrates her ties to Whistler and East Asian art. From her diaries in March 1905 one learns of her enthusiasm for Japanese art : “The Japanese are so artful, so obsessed with their thirst for culture.” And of relevance to her later painting and Jawlensky's, she reports something remarkable: “Some new impressions of color values ”a visit to the Japanese theater in Munich gave her.

When Werefkin returned to artistic activity in 1906 after ten years of abstinence from painting, she immediately and very directly resorted to Japanese. Through her portrayals of the dancer Alexander Sacharoff with a Japanese make-up mask and in a Mie pose , it has long been known that she had developed a soft spot for Far Eastern culture.

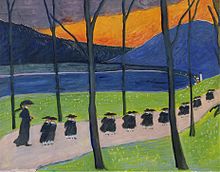

Her landscape paintings were not unaffected either, for example in her painting Autumn (School) she treated the trees as vertical compositional elements in the Japanese way and cut off the crowns with the upper edge of the picture. Werefkin had got to know something similar at the latest in 1902 through the magazine Mir Iskusstwa through the reproduction of a forest path to Utagawa Hiroshige . Other motivic building blocks that Werefkin borrowed from Japanese art included a. the forced perspective, the towing fold , the post as an image divider or drum bridge .

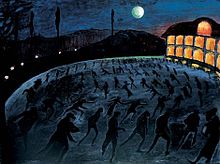

Reflections on Japanese woodcut art can be traced back to Werefkin's older work. In the mid-1920s, for example, cast shadows suddenly came into use again, for example pronounced in the painting L'équipe de nuit from 1924/25 or in her painting Ave Maria from around 1927. They should be a return to models and the like. a. to be explained by Hiroshige. The processional parades of the Way of the Cross I and Way of the Cross II from 1926/28 could not do without Japanese models, for example by Kawanabe Kyōsai (1831–1889). Likewise, the monsters in the picture Der Sieger from 1930 could be based on depictions of monsters from the "Japanese spirit cult" e.g. B. from Utagawa Kuniyoshi , go back.

Honors

The artist is the namesake of the " Marianne Werefkin Prize ", which has been awarded since 1990 by the Association of Berliner Künstlerinnen 1867 e. V. is awarded to contemporary female artists every two years.

Collections

Significant works by Werefkin in the art collections:

- Fondazione Marianne Werefkin , Ascona

- Municipal gallery in the Lenbachhaus , Munich

- Wiesbaden Museum , Wiesbaden

Works (selection)

Painting with your own article:

- Portrait of Vera Repin , 1881

- Self-portrait in a sailor's blouse , 1893

- Portrait of Alexej Jawlensky , 1896

- Beer garden , 1907

- The stone pit , 1907

- Tempête , 1907/08

- Sunday afternoon , 1908

- In the café , 1909

- Jawlensky in the Chambre séparée , around 1909

- Sacharoff , 1909

- Helene , around 1909

- Madame , around 1909

- Female figurine , around 1909

- Tragic mood , 1909

- Twins , 1909

- Circus (before the performance) , 1910

- City in Lithuania , 1910

- The red tree , 1910

- Into the night , 1910

- Summer stage , 1910

- Shingle factory , 1910

- Self-Portrait I , 1910

- The Ice Skaters , 1911

- The steep coast of Ahrenshoop , 1911

- Corpus Christi , around 1911

- Factory town , 1912

- Église St. Anne , 1914

- Poste de police à Vilnius , 1914

- Snow vortex , 1916

- Le Chiffonier , 1917

- The Way of the Cross II , 1926/27

- Ave Maria , 1927

- Ernst Alfred Aye , 1927

- After the storm , 1932

Exhibitions (selection)

- 1914 Baltiska Utstallnigen . Malmö Baltic Exhibition

- 1959 Marianne von Werefkin - memorial exhibition 1860-1938 . Municipal gallery in the Lenbachhaus and Kunstbau Munich

- 1980 Marianne Werefkin, paintings and sketches . Wiesbaden Museum

- 2014: Marianne Werefkin: From the Blue Rider to the Big Bear . Municipal Gallery Bietigheim-Bissingen and Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum , Bremen

- 2015: Sturm-Frauen - female artists of the avant-garde in Berlin 1910–1932 . Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt

- 2019: Lebensmenschen: Alexej von Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin . Municipal gallery in the Lenbachhaus and Kunstbau Munich

Movie

- Dietmar N. Schmidt: Marianne Werefkin, painter and muse. Hessen 3, 1990.

- Angelika Lizius: Russians in Bavaria - The painter Marianne von Werefkin. Documentary film. Bayerischer Rundfunk, 2007.

- Stella Tinbergen: ... because this is where modernity begins. Documentary about Marianne von Werefkin. 3sat, 2008.

- Stella Tinbergen: Marianne von Werefkin, I only live by the eye documentary. 3sat, 2009.

- Ralph Goertz: Lebensmenschen - Alexej von Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin , Production: IKS - Institute for Art Documentation 2019, © Lenbachhaus Munich / Museum Wiesbaden / IKS - Media Archive.

radio play

- Ute Mings: Kandinsky, Münter, Jawlensky, Werefkin and Co., Die Neue Künstlervereinigung München (1909–1912). Bayerischer Rundfunk 2, 2009.

literature

- Bernd Fäthke : Marianne Werefkin, Life and Work 1860–1938. Prestel, Munich 1988;

- Bernd Fäthke: Securing evidence for the Blue Rider in Lithuania. 6. Announcement from the Association of Berlin Artists V., Berlin 1995; Marianne Werefkin and Wassily Kandinsky. In: Der Blaue Reiter and its artists. Exhibition catalog. Brücke-Museum, Berlin 1998, p. 93 ff;

- Bernd Fäthke: 1911, The Blue Rider with Jawlensky in Ahrenshoop, Prerow and Zingst, Blue Rider in Munich and Berlin. 8. Announcement by the Association of Berlin Women Artists, Berlin 1998;

- Bernd Fäthke: Werefkin and Jawlensky and Werefkin with son Andreas in the "Murnau period". In: 1908–2008, 100 Years Ago, Kandinsky, Münter, Jawlensky, Werefkin in Murnau. Exhibition catalog. Murnau 2008, p. 31 ff; Marianne Werefkin. Hirmer-Verlag, Munich 2001;

- Bernd Fäthke: Marianne von Werefkin. In: Expressionismus auf dem Darß, Aufbruch 1911, Erich Heckel, Marianne von Werefkin, Alexej Jawlensky. Exhibition catalog. Fischerhude 2011, p. 38 ff;

- Bernd Fäthke: Marianne Werefkin - “the blue rider”. In: Marianne Werefkin, From the Blue Rider to the Great Bear. Municipal Gallery Bietigheim-Bissingen 2014, p. 24 ff.

- Otto Fischer : Marianna von Werefkin. In: Das neue Bild, published by the Neue Künstlervereinigung München. Munich 1912, p. 42 f, illus, p. 42, 43; Plates XXXIII, XXXIV, XXXV, XXXVI.

- Mara Folini: Marianne von Werefkin. In: Historical Lexicon of Switzerland . May 15, 2013 , accessed December 5, 2019 .

- Gustav Pauli: Memories from seven decades. Tübingen 1936, p. 264 ff.

- Marianne von Werefkin 1860–1938, Ottilie W. Roederstein 1859–1937, Hans Brühlmann 1878–1911. Exhibition catalog. Kunsthaus Zürich, 1938, p. 4 ff.

- Marianne Werefkin 1860–1938. Exhibition catalog. Municipal Museum Wiesbaden, 1958.

- Clemens Weiler (ed.): Marianne Werefkin, letters to an unknown 1901–1905. Cologne 1960.

- Valentine Macardé: Le renouveau de l'art picturale russe 1863–1914. Lausanne 1971, pp. 116 f., 127 f., 133 f.

- Marianne Werefkin, paintings and sketches. Exhibition catalog. Museum Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden 1980.

- Annekathrin Merges-Knoth: Marianne Werefkin's Russian roots . Dissertation University of Trier, 1996.

- Marianne von Werefkin, Oeuvres peintes 1907–1936. Exhibition catalog. Neumann Foundation, Gingins 1996.

- Marianne Werefkin, The color bites my heart. Exhibition catalog. Publication series Verein August Macke Haus, Bonn 1999.

- Gabrielle Dufour-Kowalska: Marianne Werefkin, Lettres à un Inconnu. Paris 1999.

- Marianne Werefkin, Il fervore della visione. Exhibition catalog. Palazzo Magnani, Reggio Emilia 2001.

- Marianne von Werefkin in Murnau, art and theory, role models and artist friends. Exhibition catalog. Murnau 2002.

- Nathalie Jagudina: Marianne von Werefkin - Selected writings and letters 1889–1918. Content evaluation in the art-technological context. Thesis . Bern University of the Arts, Department of Conservation and Restoration, Bern 2008.

- Ingrid Pfeiffer, Max Hollein (eds.): Sturm-Frauen: Artists of the Avant-Garde in Berlin 1910-1932 . Wienand, Cologne 2015, ISBN 978-3-86832-277-4 (catalog of the exhibition of the same name, Schirn Kunsthalle Frankfurt , October 30, 2015 to February 7, 2016)

- Brigitte Roßbeck: Marianne von Werefkin. The Russian from the Blue Rider's circle. Siedler, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-88680-913-4 ; the same: Marianne Werefkin - your life - in the Russian Empire - in Germany - in Switzerland. In: Marianne Werefkin, From the Blue Rider to the Great Bear. Exhibition catalog. Municipal Gallery Bietigheim-Bissingen 2014, ISBN 978-3-927877-82-5 , p. 8 ff.

- Brigitte Salmen (Ed.): "... these tender, spirited fantasies ..." The painters of the "Blauer Reiter" and Japan. Exhibition catalog. Murnau Castle Museum, 2011, ISBN 978-3-932276-39-2 ; the same: Marianne von Werefkin . Hirmer, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-7774-3306-6 .

- Brigitte Salmen, PSM Private Foundation Schloßmuseum Murnau: Marianne von Werefkin, Life for Art . Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-7774-2048-6 .

- Tatiana Kuschtewskaja: Russians without Russia. Famous Russian Women in 18 Portraits . Grupello, Düsseldorf 2012, ISBN 978-3-89978-162-5 .

- Tanja Malycheva and Isabel Wünsche (eds.), Bernd Fäthke, Petra Lanfermann u. a .: Marianne Werefkin and the Women Artists in Her Circle (Marianne Werefkin and the women artists in her circle) , Jakobs University, Bremen 2016 (English) ISBN 978-90-04-32897-6

- "In close friendship". Alexej Jawlensky, Paul and Lily Klee, Marianne Werefkin. The correspondence. Edited by Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, and by Stefan Frey. Zurich 2013, ISBN 978-3-909252-14-5 .

- Marianne Werefkin: From the Blue Rider to the Big Bear. Exhibition catalog. Municipal Gallery Bietigheim-Bissingen 2014, ISBN 978-3-927877-82-5 .

- Roman Zieglgänsberger, Annegret Hoberg, Matthias Mühling (eds.): Lebensmenschen - Alexej von Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin , exhibition catalog. Municipal gallery in the Lenbachhaus and Kunstbau, Munich / Museum Wiesbaden, Munich a. a. 2019, ISBN 978-3-7913-5933-5 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Marianne von Werefkin in the catalog of the German National Library

- Marianne von Werefkin. In: FemBio. Women's biography research (with references and citations).

Individual evidence

- ↑ Regarding the often incorrect conversion of dates from the Julian into the Gregorian calendar, it must be noted that although the time difference was 13 days in the October Revolution in the 20th century, only a difference of 12 days applies to the 19th century.

- ↑ S. Kubickienė: Vyžuonėlių Dvaras. Utenis, July 12, 1994.

- ^ Annekathrin Merges-Knoth: Marianne Werefkin's Russian Roots - New Approaches to the Interpretation of Her Artistic Work. Dissertation. (PDF, 15.02 MB) University of Trier , September 18, 2001, accessed on March 17, 2019 .

- ↑ Marianne Werefkin, letter to Herr Schädl, 1919, Archive Fondazione Marianne Werefkin, Ascona, p. 2 f.

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Marianne Werefkin and her influence on the Blue Rider. In: Marianne Werefkin, paintings and sketches. Exhibition catalog. Museum Wiesbaden 1980, p. 17.

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: In the run-up to Expressionism, Anton Ažbe and painting in Munich and Paris. Wiesbaden 1988.

- ↑ Valentine Macardé: Le renouveau de l'art russe picturale 1863-1914. Lausanne 1971, p. 135 f.

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Marianne Werefkin. Munich 2001, p. 47, fig. 52

- ↑ Brigitte Roßbeck: Marianne von Werefkin: The Russian woman from the circle of the Blue Rider. Munich 2010, pp. 87–91.

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Jawlensky and his companions in a new light. Hirmer-Verlag, Munich 2004, p. 86 ff.

- ↑ Brigitte Salmen, Annegret Hoberg: Around 1908 - Kandinsky, Münter, Jawlensky and Werefkin in Murnau . In: 1908–2008, 100 Years Ago, Kandinsky, Münter, Jawlensky, Werefkin in Murnau. Exhibition catalog. Murnau 2008, p. 16.

- ↑ Isabell Fechter: Sternstunden, Murnau 1908/2008 - 100 years ago . In: Weltkunst. 09/2008, p. 96 f.

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Werefkin and Jawlensky with their son Andreas in the "Murnauer Zeit" . In: 1908–2008, 100 Years Ago, Kandinsky, Münter, Jawlensky, Werefkin in Murnau . Exhibition catalog. Murnau 2008, p. 53 ff.

- ^ Letter from Erbslöh to Kandinsky of January 25, 1909. In: Annegret Hoberg, Titia Hoffmeister, Karl-Heinz Meißner: Anthology . In: The Blue Rider and the New Image, From the "New Munich Artists' Association" to the "Blue Rider". Exhibition catalog. Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich 1999, p. 29.

- ↑ Alexej Jawlensky: Memoirs . In: Clemens Weiler (ed.): Alexej Jawlensky, Heads - Faces - Meditations . Hanau 1970, p. 110 f.

- ↑ George Mauner: From Pont-Aven to the "bridge" - Amiet as "pons inter pontes" . In: Cuno Amiet: From Pont-Aven to the “bridge” . Exhibition catalog. Kunstmuseum Bern, Bern 1999, p. 24 ff.

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Marianne Werefkin - "the blue rider's rider" . In: Marianne Werefkin, From the Blue Rider to the Great Bear . Exhibition catalog. Städtische Galerie Bietigheim-Bissingen 2014, p. 46 ff, Fig. 48

- ↑ Véronique Serrano: Chronologie et témoignages . In: Pierre Girieud et l'expérience de la modernité, 1900–1912. Exhibition catalog. Musée Cantini, Marseille 1996, p. 117.

- ↑ On these processes, see also From the NKVM to the Blue Rider .

- ^ Original in the Munich City Archives.

- ↑ Marianne von Werefkin , www.murnau.de, accessed on March 11, 2019.

- ↑ Angelika Affentranger-Kirchrath: An unequal artist couple: Willy Fries and Marianne Werefkin in Ascona ; in: Sigismund Righini, Willy Fries, Hanny Fries: an artist dynasty in Zurich, 1870-2009 , ed. by Sascha Renner on behalf of the Righini Fries Foundation; Verlag Scheidegger & Spiess, Zurich 2018, 367 pp., Ill., Pp. 215–232, esp. Pp. 225–232

- ↑ Kunst der Zeit, Organ der Künstlerelbsthilfe, Vol. II, H. 7, 1928 (Ascona special).

- ↑ Frederik Jensen (ed.): Marianne von Werefkin 1860–1938, impressions of Ascona. Galleria Via Sacchetti, Ascona 1988.

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Werefkin's homage to Ascona. In: Marianne Werefkin, The color bites my heart. Exhibition catalog. Publication series Verein August Macke Haus, Bonn 1999, p. 31 ff.

- ^ Georg Schmidt: The Fauves, history of modern painting. Geneva 1950, p. 17.

- ↑ Barbara Glauert (ed.): Claire Goll / Iwan Goll: "My soul tones" - the literary document of a life between art and love recorded in their letters. Bern 1978, p. 17 ff.

- ↑ Bruno Goetz: The divine face. Leipzig / Vienna / Munich 1927.

- ↑ Else Lasker-Schüler: Marianne von Werefkin, Complete Poems. Munich 1966, p. 223 f.

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Marianne Werefkin, from her sketchbooks. In: Weltkunst. Volume 68, No. 2, February 1998, p. 310 ff.

- ↑ Claudia Däubler-Hauschke, Impressionism and Japanese Fashion, in exh. Cat .: Impressionism and Japanese fashion, Edgar Degas / James McNeill Whistler, Städtische Galerie Überlingen 2009, p. 9.

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Von Werefkins and Jawlensky's weakness for Japanese art. In: "... the tender, spirited fantasies ...", the painters of the "Blue Rider" and Japan. Exhibition catalog. Murnau Castle Museum 2011, p. 103 ff and Fig. 3.

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Von Werefkins and Jawlensky's weakness for Japanese art. In: "... the tender, spirited fantasies ...", the painters of the "Blue Rider" and Japan. Exhibition catalog. Murnau Castle Museum 2011, p. 108.

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Marianne Werefkin. Munich 2001, p. 133 ff.

- ↑ Reproduction after Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858), In: Mir Iskusstwa. (Welt der Kunst), vol. 1902, no. 2, p. 95.

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Von Werefkins and Jawlensky's weakness for Japanese art. In: "... the tender, spirited fantasies ...", the painters of the "Blue Rider" and Japan. Exhibition catalog. Murnau Castle Museum 2011, p. 109 ff.

- ↑ Marianne Werefkin, Il fervore della visione. Exhibition catalog. Palazzo Magnani, Reggio Emilia 2001, fig. 60, p. 180.

- ↑ Marianne Werefkin, Il fervore della visione. Exhibition catalog. Palazzo Magnani, Reggio Emilia 2001, fig. 72, p. 190.

- ↑ Charlotte van Rappart-Boon, Willem van Gurlik, Keiko van Bremen-Iro: Catalog of the Van Gogh-Museurn's collection of Japanese prints. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam 1991, p. 95.

- ↑ Marianne Werefkin, Il fervore della visione. Exhibition catalog. Palazzo Magnani, Reggio Emilia 2001, fig. 45 and 46, p. 168 f.

- ↑ Charlotte van Rappart-Boon, Willem van Gurlik, Keiko van Bremen-Iro: Catalog of the Van Gogh-Museurn's collection of Japanese prints. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam 1991, p. 295.

- ↑ Marianne Werefkin, Il fervore della visione. Exhibition catalog. Palazzo Magnani, Reggio Emilia 2001, fig. 69, p. 188.

- ^ Siegfried Wichmann: Japonism, East Asia-Europe, Encounters in the Art of the 19th and 20th Century. Herrsching 1980, p. 268 ff.

- ↑ Charlotte van Rappart-Boon, Willem van Gurlik, Keiko van Bremen-Iro, Catalog of the Van Gogh-Museum's collection of Japanese prints. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam 1991, p. 87.

- ↑ Ursel Berger (Ed.): The Marianne Werefkin Prize 1990–2007. Archive Association of Berlin Women Artists 1867 eV, Georg Kolbe Museum, Berlin 2009.

- ↑ Marianne Werefkin Prize. Association of Berlin Women Artists , accessed on March 17, 2019 .

- ↑ Irene Netta, Ursula Keltz: 75 years of the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus and Kunstbau Munich . Ed .: Helmut Friedel. Self-published by the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-88645-157-7 .

- ↑ Rudolf Krämer-Badoni, you cleaned the color from the wrong light, As stormy as in the household with Jawlensky: Marianne Werefkins pictures and sketches in Wiesbaden, DIE WELT, Wednesday, October 8, 1980, p. 23; Bruno Russ, At a turning point in modern art, Marianne Werefkin - their effect and their pictures, Wiesbadener Kurier, 4./5. October 1980, p. 14; AG, West-Eastern Encounters in Pictures, On the Marianne Werefkin exhibition in the Wiesbaden Museum, Wiesbadener Tagblatt, Saturday / Sunday, 4./5. October 1980, p. 5

- ^ Announcement on the exhibition , accessed on August 6, 2014.

- ^ Digitized version , accessed on March 5, 2011.

- ^ Marianne von Werefkin - Selected Writings and Letters 1889-1918. Content evaluation in the art-technological context. www.yumpu.com, accessed March 17, 2019 .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Werefkin, Marianne von |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Верёвкина, Марианна Владимировна (Russian); Werjowkina, Marianna Vladimirovna (transcription); Verëvkina, Marianna Vladimirovna (scientific transliteration) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian expressionist painter |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 10, 1860 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Tula , Russian Empire |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 6, 1938 |

| Place of death | Ascona , Switzerland |