Alexej von Jawlensky

Alexej von Jawlensky (originally Alexei Georgievich Jawlenski ; Russian Алексей Георгиевич Явленский , scientific. Transliteration Alexei Georgievic Javlenskij ; born March 13 . Jul / 25. March 1865 greg. Or 1864 near Torzhok , Russian Empire ; † 15. March 1941 in Wiesbaden ) was a Russian- German painter who also worked in Switzerland and Germany. As a painter of Expressionism, Jawlensky is part of the community of artists, Der Blaue Reiter , initiated by Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc .

biography

Jawlensky's year of birth

There are several versions of Jawlensky's year of birth. For example, “it says on the registration slip in Munich […] 1866, corrected to 1864!” Another representation in 1924 wanted to make you believe that Jawlensky did not see the light of day until one year later - namely in 1867. Since the great monograph from 1959 by Clemens Weiler , the first Jawlensky biographer , the idea that 1864 was Jawlensky's year of birth has been solidified. Without any evidence, he introduced his book with the words: "Alexej Georgewitsch Jawlensky was born on March 13, 1864 in the old style [...]." Weiler's opinion agreed - without giving any arguments - for example the authors of the Jawlensky catalog raisonné 1991 on. It was not until almost forty years after Weiler in 1998 that the author Jelena Hahl-Fontaine gave a justified contradiction . After doing research in the “Central State Military History Archive in Moscow”, she explained: “Most of the facts [...] have recently started to speak for the year 1865.” a. from the fact that Jawlensky presented various documents for the entrance examination at the Academy in Saint Petersburg , including “a certified copy of his birth certificate. In addition, he had to fill out a form at the same time, where he entered his date of birth again by hand […] March 13, 1865. “As an accompanying measure, Hahl-Fontaine consulted the military service lists of Jawlensky's father, Georgi Nikiforowitsch Jawlensky (April 26, 1826 - March 6, 1885) and found Alexei's date of birth with “13. March 1865 "confirmed. The latter version found its way into the 2004 catalog of the Wiesbaden exhibition “Jawlensky, Meine liebe Galka!” Fifteen years later - in 2019 - the 1998 discovery was reversed. Obviously Jawlensky knew himself never quite sure when and where he was born, for he wrote in his memoirs, the reader irritating: "My old nurse Sikrida told me that I was in Torzhok was born or in a small town near Torzhok in Tver Governorate . She said, 'You were born on the way.' “This passage from Jawlensky's memoirs was ignored by all authors who dealt with Jawlensky's date of birth. Unconsidered remained that it was quite common in Tsarist Russia, through bribery of official papers with bogus data to arrive, such as birth certificates or passports. The Russian painter Jehudo Epstein describes this earlier practice in dealing with bribes, so-called “takings” in his book “My way from east to west” very vividly.

In Russia 1864 / 1865-1896

Jawlensky was born as the fifth child of six siblings in 1864 or 1865. His father, Colonel Georgi Nikiforowitsch Jawlensky, died when the son was 17 or 18 years old. His mother, Alexandra Petrovna Medvedeva, was his father's second wife. At sixteen he lived with his family in Moscow with the aim of becoming an officer. At the All-Russian Industrial and Art Exhibition in Moscow in 1882 he saw paintings for the first time, discovered his love for painting and began to train his painting and drawing skills as a self-taught person by visiting the Tretyakov Gallery on Sundays and holidays . As an officer, he was transferred from Moscow to Saint Petersburg in 1889 . Only there Jawlensky, as a penniless tsarist ensign in the military, was able to attend the Russian Art Academy on evenings .

At the academy he was trained in drawing on plaster of Paris. At this institution in 1890 he met the famous representative of Russian realism , Ilya Repin (1844–1930). In 1892 he received the recommendation from him to learn oil painting from his former private student, the wealthy Baroness Marianne von Werefkin (1860–1938). At that time she had already achieved considerable success as a painter in Russia, which had earned her the nickname “Russian Rembrandt”. She trusted her instinct that Jawlensky was predestined to produce a significant artistic work with appropriate support. Few of his realistic pictures have survived from before the turn of the century.

In Germany 1896–1914

In 1896 Werefkin moved with Jawlensky and her eleven-year-old maid, Helene Nesnakomoff (1885–1965), to Munich and rented a comfortable double apartment on the third floor of the Schwabing district at 23 Giselastraße. While Werefkin completely gave up her own painting for ten years in favor of Jawlensky in order to devote herself entirely to the training of her protégé, she entrusted his painting training to the Slovenian Anton Ažbe (1862–1905). Jawlensky was enthusiastic about his school, in which he worked closely with his Russian friends Igor Grabar (1871-1960) and Dmitry Kardowsky (1866-1943). Ažbe had an excellent sense for colors, the flickering of light and used a “virtuoso painting technique”. The artists of the Munich School - Lovis Corinth (1858–1925), Wilhelm Leibl (1844–1900), Wilhelm Trübner (1851–1917), Carl Schuch (1846–1903) and Leo Putz (1869–1940) - were for them Jawlensky's development is important.

A characteristic oil painting of his style phase influenced by Ažbe is the portrait of Helene fifteen years old (CR 13) of the maid of his partner, Helene Nesnakomoff, signed in the picture and dated 1900 . Two years later, at the age of 16, she gave birth to their son Andreas . It is a threshold picture, not only in terms of painting technique. Stylistically, too, with its “ Lenbach brown ” tones, it harks back to his previous realistic paintings (CR 7, 8, 11) in a Janus-headed manner , in order to simultaneously mark the beginning of further “work with broad lines” in the years to come.

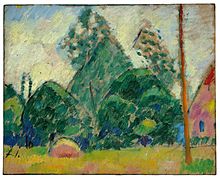

Jawlensky's first orientation towards the Parisian avant-garde marked the year 1902, when he began to design still lifes and landscapes in the neo-impressionist style. In 1903 Jawlensky traveled to Paris . His painting Das Waldhäuschen from that year confirms his engagement with the art of van Gogh , which occupied him from 1904 to 1906.

The painting Dance in the Open (CR 25) is a remarkable picture in Jawlensky's further development in the painting of the artificial play with light and shadow. The picture was extensively examined and offered a number of surprises. It was created shortly before September 1903, when Werefkin had traveled to Normandy with the Russian painter Alexander von Salzmann (1874–1934) - without Jawlensky . An X-ray shows that there is an earlier portrait under the present image. It depicts a lady in a black skirt, the style of which can be derived from the painting Helene in Spanish costume (CR 21, 1901/1902). According to reports by Jawlensky and Werefkin, the painting can be dated to 1904, which makes it another key image and forerunner to works such as Abend in Reichertshausen (CR 68), where the artist couple stayed during the summer from June to September 1904. A comparison with earlier paintings shows that Jawlensky's painting was again in upheaval. Elongated, calligraphic strips of color point back to his handwriting, which was trained by Ažbe, which stands in a strange contrast to the flat character of the background of flakes and ticks of color. The latter testify that he dealt with young French art at the time. In the meantime his painting became more colorful.

Jawlensky spent the year 1905 in Germany. In and around Füssen in the Allgäu he painted a series of colorful pictures. Some allow a clear identification of the location, e.g. B. the representation of the Füssen Castle with the monastery of Sankt Mang in front of it (CR 99). These paintings are still clearly influenced by Neo-Impressionism and the handwriting of Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890). The six paintings that he sent to the exhibition in the Russian section of the third edition of the Salon d'Automne in Paris, organized by Sergei Pavlovich Djagilew (1872–1929), also belong to this style phase . B. Mixed Pickles (CR 75) It was Jawlensky's mistake that in his memoirs he dated his much-cited trip to France, which took him with Werefkin in 1906 from Carantec in Brittany via Paris and Arles to Sausset-les-Pins , "1905". Here near Marseille on the Mediterranean , where her painter friend Pierre-Paul Girieud (1876–1948) lived, Werefkin resumed her painting activity. Alexej von Jawlensky used the trip south to pay homage to Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), who had just passed away . The resident of Munich spent a whole year painting it. For the fourth edition of the Salon d'Automne in Paris, Jawlensky gave several Brittany studies in 1906 . They were exhibited in the Russian department curated by Sergei Diagilew and can no longer be determined today.

Jawlensky and Werefkin spent Christmas 1906 in Sausset-les-Pins before traveling back to Munich in January 1907 via Geneva , where they paid a visit to Ferdinand Hodler (1853–1918). In the second half of February 1907, Jawlensky met the Berlin neo-impressionist Curt Herrmann (1854–1929) and the painter monk and Nabi artist Jan Verkade (1868–1946), who also wrote theoretical writings under his pseudonym “Langejan” at the Münchner Kunstverein . Until 1908 Verkade painted frequently in Jawlensky's studio. In August, Jawlensky and Werefkin's stay in Markt Kaisheim in the Donau-Ries district can be traced. A month later, as evidenced by several dated sketches by the Werefkin, they were in Wasserburg am Inn . In October, dated sketches by the Werefkin also document the visit of the painter couple in the Murnau market on the Staffelsee . In early December 1907, Verkade's long-time friend Paul Sérusier (1864–1927) came to Munich. The painter Hugo Troendle (1882–1955) had rented a studio for him not far from Jawlensky's apartment. Sérusier introduced the three colleagues to Paul Cézanne's painting style, which can be seen particularly well in Jawlensky's Still Life (CR 177).

In the spring of 1908, Jawlensky remained loyal to the "fathers of modernity" with his painting, but increasingly discovered the art and art theory of Paul Gauguin (1848–1903). With financial support from Werefkins, he acquired van Gogh's painting Die Strasse in Auvers / La maison du père Pilon from Franz Josef Brakl's (1854–1935) art dealer . It took a foreign, Jawlensky particularly impressive authority before he could decide to finally give up his painting, which was based on pointillism . At Easter 1908 Jan Verkade introduced the painter to Władysław Ślewiński (1854–1918), the Polish friend of Paul Gauguin (1848–1903). Slewinski, who had a pronounced aversion to “splashes of color” - Neo-Impressionists - brought Jawlensky away from painting in dots and ticks and persuaded him to convert to Gauguin's flat painting. (Compare CR 184 with 222). Only because Jawlensky took this step was he able to advance to a pioneering teacher for Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944), Gabriele Münter (1877–1962) and other Munich colleagues for a while.

In the summer of 1908 the legendary collaboration between Werefkin / Jawlensky and Münter / Kandinsky started. It is possible that afterwards the relationship between the two painter couples clouded over for a short time. Because at Christmas 1908, Werefkin, Jawlensky, Adolf Erbslöh (1881–1947) and Oscar Wittenstein (1880–1918) had the idea of founding the New Munich Artists' Association (NKVM). In any case, Münter and Kandinsky were initially not involved in the project. Kandinsky was still annoyed about this years later. The dissatisfaction explains to a certain extent his hesitant behavior when he was offered the chairmanship of the NKVM in January 1909. In January 1909 the manuscript for founding the NKVM was written and Kandinsky was elected first chairman. From May to September the two artist couples worked together again in Murnau. The dancer Alexander Sacharoff (1886–1963) was preparing his big performance at the Odeon in Munich with Werefkin and Jawlensky .

On December 1st, the opening of the first exhibition with 16 artists took place, which received a lot of criticism in the press. Shortly afterwards, Jawlensky's relationship with Werefkin had once again deteriorated very much, whereupon she traveled to Kaunas in Russian Lithuania. There she spent the winter of 1909 and the spring of 1910 with her brother Peter von Werefkin (1861-1946), who was governor there from 1904 to 1912 .

At Easter in 1910, Werefkin was back in Munich. In May Erbslöh, an intimate of the Werefkin and secretary of the NKVM, went to France in order to win French artists together with Pierre Girieud (1876–1948) to participate in the second NKVM show. The opening was on September 1st. A total of 29 artists took part this time, with the proportion of “savages” from Russia and France being relatively high. This exhibition was also mocked by the press and the public. Franz Marc (1880–1916) visited the exhibition incognito and wrote a review about the ranting tirades, which came into the hands of Erbslöh at the end of September. Shortly afterwards, Marc had his first contact with the artists of the NKVM. With Werefkin and especially Jawlensky it came "very quickly to a personal and artistic understanding". Even August Macke (1887-1914) and his wife Elisabeth (1888-1978) visited in those days the first time Jawlensky and Werefkin. Kandinsky returned from Russia just before Christmas. On December 31, Franz Marc and the painter Helmuth Macke (1891–1936), August Macke's cousin, met Kandinsky for the first time in the Werefkin's salon.

A special highlight for Kandinsky and Marc was a concert by Arnold Schönberg (1874–1951) on January 2, 1911, which they attended with Werefkin, Jawlensky, Münter and Helmuth Macke. This triggered a trend-setting discussion about the "dirt" in painting, an artistic problem that Werefkin had already solved in 1907 and implemented in her paintings. When there were more and more disagreements among the conservative forces of the NKVM because of Kandinsky's increasingly abstract painting, he resigned the chairmanship of this association on January 10th. Erbslöh became his successor. From the beginning of May Girieud lived with Werefkin and Jawlensky when he and Marc showed his paintings in an exhibition at the Modern Gallery Heinrich Thannhauser .

In June, Jawlensky and Werefkin were with Helene and Andreas for the summer in Prerow on the Baltic Sea . At that time Jawlensky experienced an important high point in his expressionistic work: "I painted there [...] in very strong, glowing colors, absolutely not naturalistic and material [...] This was a turning point in my art." In 1911 there was his first solo exhibition in Barmen . Particularly revealing pictures from this creative period are Der Buckel I (CR 381), An der Ostsee (CR 416) or Church in Prerow (CR 422). At the end of the year they went to Paris, where they met Henri Matisse (1869–1954) personally. When the jury for the third exhibition of the NKVM rejected Kandinky's painting Composition V / The Last Judgment on December 2nd , he left the association with Münter and Marc to present the first exhibition of the editorial team “ Der Blaue Reiter ” in the winter of 1911/1912 that they had prepared for a long time. Münter was privy to the intrigue from the start, as is evident from a letter from Kandinsky on August 6, 1911. At that time he reported to Münter about the status of the preliminary work: “I paint and paint now. Lots of sketches for the Last Judgment. But I am dissatisfied with everything. But I have to find out how to do it! Just be patient. ”Macke was a confidante. It was not until more than twenty years later that Kandinsky revealed his and Marc's unfair game for the first time: "Since we both sensed the noise earlier, we had prepared another exhibition." It became even clearer on November 22, 1938 in a two-page letter to Galka Scheyer .

Jawlensky and Werefkin spent the summer of 1912 together with Kardowsky and his wife, Olga Della Vos (1875–1952), a successful painter, in the Oberstdorf market . This year marks the zenith of Jawlensky's expressionist work. Striking pictures are especially his portraits, e. B. Turandot II (CR 468) or his self-portrait (CR 477), and also his landscapes mountains near Oberstdorf (CR 545) or Blue Mountains (CR 556). When they returned to Munich from Oberstdorf, Werefkin and Jawlensky found the noble book “Das Neue Bild” by Otto Fischer , which was supposed to serve as the NKVM's publication for the winter exhibition. Werefkin and Jawlensky were outraged by its text and the explanations about the individual artists, whereupon they left the NKVM. Shrunk to eight participants, the NKVM opened its third exhibition at the same time as the first of the “Blue Rider” on December 18. The NKVM was officially held from the Munich register of associations by Erbslöh in 1920. In autumn 1912 Jawlensky also met Emil Nolde at the exhibition in Munich, whereupon the two painters became friends.

In 1913 Werefkin and Jawlensky took part in the exhibition of the editorial team “Der Blaue Reiter” in the Berlin gallery “Der Sturm” by Herwarth Walden (1878–1941) as well as in his art exhibition First German Autumn Salon . As on several occasions, the relationship between Werefkin and Jawlensky was not the best. So she went back to her Lithuanian homeland to see her brother Peter, who had become governor of Vilnius in 1912 . Jawlensky's painting lost its previous fiery colors, e.g. B. Woman with Forelock (CR 584) or Portrait of Sacharoff (CR 601). In January 1914, Jawlensky tried to find sources of money in order to survive the separation from his patron. It is therefore surprising to find Jawlensky listed in the Journal de Bordighera on February 12, 1914 as a guest of the posh seaside resort on the Italian Riviera . There were without exception cheerful and luminous pictures that differ significantly from the gloomy and dark pictures of the previous year. Various of these paintings show details that can still be found on site today, e.g. B. House in Bordighera (CR 623) or Festival of Nature - Bordighera (CR 624). When Jawlensky returned to Munich from Bordighera, he found the apartment on Giselastrasse in Werefkin still orphaned. So he went to Russia to persuade Werefkin to return to Munich, which he finally succeeded in doing. At the end of June he was back in Munich, Werefkin on July 26th, six days before the outbreak of the First World War .

In Switzerland 1914–1921

When Germany expelled its foreigners, Jawlensky and Werefkin emigrated to Switzerland with their maid Helene Nesnakomoff and their son Andreas, whom Jawlensky had fathered with Helene. At first they lived in modest circumstances in Saint-Prex on Lake Geneva . From then on, Jawlensky had to say goodbye to the luxurious life that Werefkin had offered him so far. In his small room, sitting by the window, he tried to paint something special from the landscape of Lake Geneva. The individual image elements, the lake, trees and bushes, are initially clearly recognizable, e.g. B. The way, mother of all variations (CR 644). Over time, the details taken from nature developed into metaphors from the invisible worlds of feeling, soul and spirit. Jawlensky found the first works that arose as “songs without words”. Officially he called them Variations on a Landscape Theme . With them he had outgrown himself as a painter, without initially realizing it. These pictures, painted in series, were the beginning of an incomparable oeuvre, in which the earlier expressionist wrested new values from colors and shapes with increasing age. At the end of the long chain of variations is the picture Mystery (CR 1166). The painting of heads in the years 1915–1918 is related to these variations.

In 1916 a new woman entered Jawlensky's life, Galka Scheyer (1889–1945) , twenty-five years his junior . She was to take on Werefkin's role as a patron of his art in the future, with the difference that he had to give her 45% of his income from the sale of paintings to her by contract.

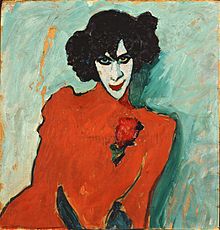

At the end of September 1917, Jawlensky and Werefkin moved with Helene and Andreas to Wollishofen near Zurich , where he began to paint his series of Mystical Heads. The human face served as his inspiration. As a rule, these are female heads. Sometimes they are characterized by a strong color, e.g. B. the portrait of Galka (CR 880). Also in 1917, Jawlensky began to paint faces that are different from all others. He called them "Christ heads". They are easy to recognize by the pointed strands of hair that sometimes cross over each other on the forehead and symbolize Christ's crown of thorns, e.g. B. Christ (CR 1118) or Resting Light (CR 1149). The CR lists 64 copies. They are represented in all groups of works up to 1936, e.g. B. Meditation, March 1936, n. 16 (CR 1848).

In spring 1918 the couple moved to Ascona on Lake Maggiore in the canton of Ticino . From the Mystical Heads, Jawlensky gradually developed a new series of head images, the Constructive Heads or Savior Faces. These are now shoulderless, the neck is still indicated, whereby real references to the material world have been largely reduced. The faces are not yet shown strictly frontal, they can be tilted to the left or right. Depending on the compositional idea, he designed them with open (CR 1072) or closed eyes (CR 1146). He came back to this topos several times until 1928 (CR 1456). 1920 sent Jawlensky from Ascona to the Biennale of Venice "3 Savior faces and two new". At that time he had just started the series of his Abstract Heads , a further development of the Savior's Faces. He made seemingly minimal changes to them in order to have a big impact. By renouncing the suggestion of the neck, he moved further away from a concrete possible human model: All abstract heads have a heraldic U-shape, they are always seen from the front, they always have closed eyes (e.g. CR 1293 or 1355) . The individual forms are more geometric than before. Full circular shapes, smaller and larger segments of circles contrast conspicuously with the picture elements. Between May and July 1920, Werefkin and Jawlensky dissolved their joint household in Munich. At the same time Jawlensky had a solo exhibition in the gallery of Hans Goltz (1873–1927). In the organ of his gallery Der Ararat he informed u. a. about a technical novelty that is still decisive today for assessing the authenticity of his works of art: "All works [...] are painted on French oil paper with oil paints." What is meant is "linen-structured paper" as the image carrier that Jawlensky did not use until 1914 in exile I got to know Switzerland and from then on used it frequently.

In Germany 1921–1941

Galka Scheyer had organized Jawlensky's participation in an exhibition at the Nassauischer Kunstverein in Wiesbaden in 1921 . For him it was not only a financial success: "I met very nice people there and that determined me to take my residence in Wiesbaden," he reports in his memoirs. In 1922 Jawlensky separated from Werefkin and married her maid Helene in Wiesbaden in July.

In contrast to most of his colleagues, Jawlensky had never bothered with the production of graphics before . Obeying the recent need, he then dealt with lithography and etching at his new place of residence . At the Nassauischer Kunstverein he published six lithographs, heads in black and white, as a portfolio. Around the same time he created etchings, of which only four were known for a long time, until 1987 when the printing plates of four more of his etchings appeared in Wiesbaden. In 1924, Scheyer agreed with Jawlensky, Kandinsky, Paul Klee (1879–1940) and Lyonel Feininger (1871–1956) to form a network in order to promote and sell their works in the USA under the name “ Die Blaue Vier ” . The association's first exhibition was in San Francisco in 1924 . In the following years, however, Jawlensky's sales success was mixed.

As far as lasting friendships were concerned in Wiesbaden, he did not find them until 1927 with two women, Lisa Kümmel and Hanna Bekker vom Rath . Along with Hedwig Brugmann and Mela Escherich, both belong to the so-called. "Emergency helpers" of the artist. They took care of him in every way. He had met the craftsperson Kümmel in the spring. With her and another 25 members he belonged to the Free Art Association of Wiesbaden . Until his death, she did all of his business and personal work, looked after his pictures, compiled his first catalog raisonné and, according to his dictation, wrote down his memoirs.

When his rheumatoid arthritis became noticeable in June 1927 , Jawlensky went to Bad Wörishofen for his first spa stay . He met the painter, sculptor and art dealer Bekker vom Rath at the end of the year. In 1929 she founded the "Association of Friends of Alexej von Jawlensky's Art" in the hope of being able to provide him with the financial support he needed to live.

When the symptoms of paralysis increased in 1930, he went to a clinic in Stuttgart for three months with the financial support of the painter Ida Kerkovius (1879–1970) . Soon afterwards he traveled to the Slovak spa town Piešťany . Jawlensky's pain was only relieved temporarily. He was often confined to bed for months and in constant need of medical care. In 1930 he applied for German citizenship, which he received in 1934. 1933 after the seizure of power of the National Socialists under Adolf Hitler also Jawlensky painting was forbidden to exhibit any.

From 1934 the strength of his painter's hand waned. Due to the progressive restriction of movement, he created new types of works. These are heads that act as a link between the abstract heads and the actual meditations. Their characteristics are a slope to the left or right. First of all, they have a rounded chin, such as B. Remembering my sick hands (CR 1473). By July at the latest, Jawlensky was forced to use his left hand to help paint. At that time, Lisa Kümmel received support from the Wiesbaden painter Alo Altripp (1906–1991) with the practical work she did for Jawlensky . Without him, the series of pictures that he called Meditations from 1937 onwards would not have been so extensive and would have had a few versions less. It was also he who first called Jawlensky the “ icon painter of the 20th century”.

Jawlensky wrote to Scheyer in February 1935 that he had already painted “more than 400 pieces” of the new heads, that they had changed again because he was only rarely able to paint curves due to the increasing crippling of his hand. In this phase, the chin of the head is cut from the lower edge of the picture, e.g. B. Review (CR 1605). Over the next few months his illness worsened, so that he could essentially only work with horizontal, vertical and oblique brush strokes. From now on, he always designed the series of images, Meditations , en face . B. Subdued embers (CR 2092). Whenever the pain subsided and the hand was more flexible again, he also painted still lifes .

We owe Altripp u. a. that in 1936 he encouraged Jawlensky to paint five pictures in the series on drawing paper covered with gold leaf, e.g. B. Meditation on a gold background (CR 2033). At this point in time, Alexej von Jawlensky was still a full member of the German Association of Artists , in whose annual exhibitions he had participated from 1930. His works at the last DKB exhibition in 1936 in the Hamburger Kunstverein can no longer be clearly identified; possibly one of them was the painting Mountains (1912), which according to Clemens Weiler's catalog raisonné is in private hands today.

Since 1937 he was dependent on a wheelchair and was only able to maintain direct contact with the outside world with the help of Kümmel. 72 of his works were confiscated in German museums, three of which were shown at the “Degenerate Art” exhibition in Munich. In December he painted his last pictures, which had become darker and almost monochrome in color, but they still appear translucent , e.g. B. The great suffering (CR 2157).

From 1938 onwards, Jawlensky suffered from complete paralysis and was confined to bed for the rest of his life. He died on March 15, 1941 at the age of 76. His coffin was laid out in front of the iconostasis of the Russian painter Carl Timoleon von Neff in the Russian Orthodox Church in Wiesbaden , whom Jawlensky knew very well as a innovator of traditional Russian icon painting from Werefkin's time. His long-time friend Adolf Erbslöh gave the funeral speech . He was buried in the Russian Orthodox cemetery very close to the church.

His estate is now managed in the Jawlensky archive in Locarno (Switzerland), which also maintains the catalog raisonné.

"A work of art is a world, not an imitation of nature."

plant

1904/1905 the first Japonisms appear in Jawlensky's oeuvre . Under the stylistic influence of van Gogh , two still lifes with a Japanese doll were created as "motivic Japaneseisms". One was called bagatelles - trivialities. The other one, referred to simply as a still life , shows the same Japanese doll. The first owners of these graceful pictures were Jawlensky's friends. Otto Fischer bought bagatelles with a blue background in 1911. Alexander Sacharoff secured the other still life with Japanese dolls against a red background . It is still only the motif that betrays Japanese influence and not a stylistic adaptation.

From this time on, a peculiarity can increasingly be observed that should become one of Jawlensky's trademarks. It is a habit to frame his paintings with a dark blue or black and blue line. Their origins can be seen as a takeover from Japanese woodcut art , which Jawlensky already knew at that time and possibly already collected. But it is also conceivable that he got to know this type of picture framing through the Nabis .

The most famous Japanese-influenced paintings by Jawlensky are his portraits of the dancer Sacharoff. The portraits in the Lenbachhaus in Munich and in the State Gallery in Stuttgart with the title The White Feather look like a poster . His lady with a fan occupies a special position in the Wiesbaden Museum , who also depicts the dancer Sacharoff, who was often painted in women's clothes.

The lady with a fan has always fascinated the viewer and is considered by many to be the epitome of feminine charm and grace. A number of borrowings in the painting make Jawlensky's reception of Japan clear. Without van Gogh's painting Oiran , the depiction of a courtesan after Keisai Eisen (1790–1848), Jawlensky's Lady with a Fan is hard to imagine. But the knowledge of various woodcuts from his own Japan collection, part of which he bequeathed to his Wiesbaden friend Lisa Kümmel , may have been the inspiration for the picture.

Jawlensky's outstanding paintings in 1912 include his self-portrait , a grandiose staging of himself that is not possible without Japanese role models. The self-portrait seems strange to many viewers and reminds one of the foreign. The unusual, exotic-looking color application on the face also contributes to this. A look at the remaining sheets of Jawlensky's Japan collection, in particular the actor's portrait by Toyohara Kunichika (1835–1900), however, makes it clear that Japanese art is a source of his artistic inspiration; especially since Kunichika is a specialist in Okubi-e pictures , "large-head representations". He decorated the face of his stage performer with a thick and mask-like make-up technique, kumadori, used in kabuki theater .

When Jawlensky got to know the Japanese woodcuts and drew from them in order to renew his own work, the openness to Japanese art was already a tradition in Western art history. However, like no other European painter before him, he transformed himself into the Japanese mastery of grasping characters and putting states of mind into the picture as his trademark. Not only the expressionist work of the "head painter" Jawlensky is influenced by this, but extends from the series of his Variations , Mystical Heads , Savior Faces , Abstract Heads and Christ Heads to the meditations of his late work.

Works (selection)

Painting with your own article:

- Portrait of Marianne von Werefkin , around 1900

- Still life with jug and book , before 1902

- Helene in Spanish costume , 1904

- Bagatelles (Jawlensky) , 1904/1906

- Peasant girl with a bonnet , before 1906

- The hunchback , 1906

- Village in Bavaria (Wasserburg / Kirch-Eiselfing) , 1907

- Summer day, 1907

- Still life with apples , 1908

- Lady with a Fan , 1909

- Nikita , 1910

- Blue Mountains (Landscape with a Yellow Chimney) , 1912

- Self-portrait, 1912 , 1912

- Woman with a forelock , 1913

- Portrait of Sacharoff , 1913

- Portrait of Sacharoff , around 1913

- Great Variation, Great Way, Evening , 1916

- Variation: 1916, Lights Tomorrow , 1916

- Mystical head: Exotic head , 1917

- Variation: around 1918 (tenderness) , around 1918

- Variation: 1921 N. 84 (Secret) , around 1921

Fakes

So far it has not been proven that the art forger Wolfgang Beltracchi , besides Max Pechstein , Max Ernst and Heinrich Campendonk, also forged Jawlensky. Long before his career as a forger, at least since the first volume of Jawlensky's Catalog Raisonné (abbreviated CR ) was published in 1991, it is common knowledge that this artist is “very popular with the forgers' guild.” Works by several anonymous painters were discovered. In the search for Jawlensky's "true work" one came across inconsistencies. Flower still lifes à la Jawlensky achieved z. B. At the beginning of the 1990s already 30,000 to 150,000 DM. The Jawlensky catalog raisonné did not mean the end of controversial questions about the authenticity of works of art; the dispute over the real Jawlenskys is still “far from over.” In the “category of endeavored replicas” were u. a. the titles Lady with a Yellow Straw Hat (CR 320), The Macedonian (CR 483), Spanish Woman with a Red Scarf (CR 486) and Schneeberge Oberstdorf (CR 539).

Paintings are and were often shown in exhibitions that distort the picture of Jawlensky's development due to faulty restorations and rough overpainting, cf. z. E.g .: peasant girl with bonnet (CR 133) or female semi-nude (CR 517). Likewise, incorrect identifications and dates obscure the artist's work and biography, such as Madame Curie (CR 83) or the portrait of Frau Epstein (CR 196). "Immortal [...] embarrassed himself in 1998 [...] the director of the Folkwang Museum in Essen, Georg W. Költzsch , with an exhibition of hundreds of allegedly newly discovered works on paper by the Russian-German expressionist" when he and Michael Bockemühl presented the exhibition "Alexej von Jawlensky "The eye is the judge" at the Folkwang Museum . The Jawlensky Archive contributed "thirty exhibits" to the Essen exhibition. As could be proven on February 2, 1998 for the watercolors and drawings, they were works that were based on Jawlensky's own and even works by other artists. Until recently, supposedly original Jawlenskys have been exposed again and again. While people sometimes rely on “gut feelings” when it comes to authenticity or forgery, the Kunsthalle in Emden went ahead of other museums with an example worthy of imitation and announced in early December 2013 that it had decommissioned two fake Jawlenskys on the basis of art-technological research. These are the Oberstdorf landscape (CR 543) and the portrait of a woman Manola with a violet veil (CR 507).

Honors

The artist is the namesake of the “Jawlensky Prize”, which has been awarded to contemporary artists every five years by the Hessian state capital Wiesbaden, the Wiesbaden casino and the Nassauische Sparkasse since 1991. The award includes a cash prize, an exhibition in the Wiesbaden Museum and the purchase of a work.

The German Federal Post Office brought on 15 February 1974 within the framework of a double issue with the German Expressionism a stamp with the head in blue worth 40 Pfennig out, the second brand to 30 pence Franz Marc Red deers shows.

Nobility title

Jawlensky's nobility is indisputable against the special Russian-social background . Since his father, as a colonel, had the hereditary nobility, and Jawlensky was also born into wedlock, there can be no serious doubt about it. In addition, as an ensign himself, he had already reached the lowest rank of the Russian nobility . However, Kandinsky already stated that Jawlensky wrongly adorns himself with a title of nobility . Officially, he himself apparently did not use the German nobility predicate "von" consistently. The latter is demonstrated on the one hand by the enamel sign of his “Signs and Painting School”, on which he simply says “A. Jawlensky ”. Likewise, he introduced himself to his contemporaries in Munich with a business card without "from". The Nabi Jan Verkade only spoke of "the Russian Alexej Jawlensky", while his partner, the painter and general daughter Marianne von Werefkin , as "Excellency v. Thrower "designated. The tombstone of Alexej von Jawlensky and his wife Helene geb. Nesnakomoff on the Russian cemetery in Wiesbaden shows the family name with the German nobility predicate. From the premarital relationship with Helene Nesnakomoff the son Andreas Jawlensky emerged in 1902 , who urged his father to marry his mother, whereby Andreas could be legitimized. Alexej married Helene, who grew up in the house of his partner Marianne von Werefkin, in 1922.

Catalog raisonné

Jawlensky's varied oeuvre is documented in a four-volume Catalog Raisonné (abbreviated CR ). The attributions contained therein are not shared by some specialists. Its appearance was delayed by a legal dispute that went through several instances and was decided by the Federal Court of Justice in 1991 . A large number of forgeries included in the catalog raisonné were found in the Jawlensky exhibition, which the Essen Museum Folkwang showed in 1998, for which the fourth volume of the CR was released at the same time. The official depreciation and the latest research results on the complete works can be found in the series Image and Science . So far it remains unclear. a. that Jawlensky's catalog raisonné states the existence of twelve paintings with the provenance of Philipp Harth , who previously owned several Jawlensky pictures. The reliability of the information is called into question because his wife wrote the following to Andreas Jawlensky about their whereabouts in 1972 : "To my great sorrow, these precious pictures were burned at the end of the war with everything else we owned."

Collections

Important works in the art collections:

- Kunstmuseum Basel , Basel

- Wiesbaden Museum , Wiesbaden

- Gunzenhauser Museum , Chemnitz

- Norton Simon Museum , Pasadena

- Municipal gallery in the Lenbachhaus , Munich

- Sprengel Museum Hannover , Hanover

- Museum Ostwall , Dortmund

- Osthaus Museum Hagen , Hagen

- State Gallery Stuttgart , Stuttgart

- Long Beach Museum of Art , Long Beach

Exhibitions (selection)

- May 15, 1914 to October 4, 1914: Baltiska Utstallningen. Malmo

- March 13, 1959 to May 3, 1959: Alexej von Jawlensky (1864-1941) . Municipal gallery in the Lenbachhaus and Kunstbau Munich

- July 17, 1964 to September 13, 1964: Alexej von Jawlensky. Municipal gallery in the Lenbachhaus and Kunstbau Munich

- February 27 to April 17, 1983: Jawlensky and painter friends. Wiesbaden Museum

- December 13, 1983 to February 5, 1984: Alexej Jawlensky, Drawings - Graphics - Documents. Wiesbaden Museum

- February 14, 2014 to June 1, 2014: Horizont Jawlensky. Alexej von Jawlensky as reflected in his artistic encounters 1900–1914. Wiesbaden Museum

- June 21 to October 19, 2014: Horizont Jawlensky. In the footsteps of van Gogh, Matisse, Gauguin. Art gallery Emden

- November 6, 2015 to February 13, 2016: Alexej von Jawlensky . Galerie Thomas , Munich

- March 19 - June 25, 2017: Alexej Jawlensky - Georges Rouault. Seeing with your eyes closed. Moritzburg Art Museum Halle (Saale)

- September 29, 2018 - January 27, 2019: Alexej von Jawlensky - Expressionism and Devotion. Gemeentemuseum, The Hague

- 2019: Lebensmenschen: Alexej von Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin . Municipal gallery in the Lenbachhaus and Kunstbau Munich

radio play

- Ute Mings: Kandinsky, Münter, Jawlensky, Werefkin and Co. Die Neue Künstlervereinigung München (1909–1912). Bayerischer Rundfunk 2, 2009

literature

- Otto Fischer: The new picture, publication of the Neue Künstlervereinigung München. Munich 1912, p. 34 ff., Plates 19-22.

- Clemens Weiler : Alexej von Jawlensky, The painter and man. Wiesbaden 1955.

- Clemens Weiler: Alexej Jawlensky. Cologne 1959.

- Hans Konrad Röthel (Ed.): Alexej von Jawlensky. Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich, July 17 - September 13, 1964.

- Clemens Weiler: Alexej Jawlensky, heads - faces - meditations. Hanau 1970, ISBN 9783876272177 .

- Ulrich Schmidt: Jawlensky, Alexej von. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 10, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1974, ISBN 3-428-00191-5 , pp. 370-372 ( digitized version ).

- Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden (Ed.): Alexej Jawlensky 1864–1941. Exhibition catalog. Munich 1983, ISBN 3-7913-0629-4 .

- Bernd Fäthke : Alexej Jawlensky, drawing - graphics - documents. Wiesbaden 1983.

- Maria Jawlensky, Lucia Pieroni-Jawlensky, Angelica Jawlensky (eds.): Alexej von Jawlensky, Catalog Raisonné . Volume 1-4. Munich 1991–1998

- Volker Rattemeyer (Ed.): Alexej von Jawlensky on the 50th year of death, paintings and graphic works. Wiesbaden 1991, ISBN 978-3892580157 .

- Alexej von Jawlensky and his group. Friends. Colleagues. Stations. Exhibition catalog Galerie Neher Essen, with works by Alexej von Jawlensky, August Macke, Franz Marc, Gabriele Münter, Marianne von Werefkin, Lyonel Feininger, Wassily Kandinsky, Paul Klee. Oberhausen 1991, ISBN 3-923806-14-0 .

- Bernd Fäthke, Alexander Hildebrand, Ildikó Klein-Bednay: Jawlensky's Japanese woodcut collection. A fairytale discovery . An exhibition of the administration of the state palaces and gardens in the knight's hall of the palace in Steinau an der Strasse, Homburg 1992, ISBN 978-3795413538 .

- Ingrid Koszinowski: Alexej von Jawlensky, paintings and graphic works from the collection of the Wiesbaden Museum. Wiesbaden 1997, ISBN 3-89258-032-4 .

- Tayfun Belgin (Ed.): Alexej von Jawlensky. Travel, friends, changes. Exhibition catalog Museum am Ostwall Dortmund, with contributions by Ingrid Bachér, Tayfun Belgin, Andrea Fink, Itzhak Goldberg, Andreas Hüneke , Mario-Andreas von Lüttichau and Armin Zwei. Heidelberg 1998, ISBN 3-8295-7000-7 .

- Tayfun Belgin: Alexej von Jawlensky, An artist biography. Heidelberg 1998, ISBN 3-8295-7001-5 .

- Helga Lukowsky: Jawlensky's evening sun, the painter and the artist Lisa Kümmel. Königstein / Taunus 2000.

- Museum Wiesbaden (Ed.): Jawlensky, Meine liebe Galka! Exhibition catalog. Wiesbaden 2004, ISBN 3-89258-059-6 .

- Bernd Fäthke: Jawlensky and his companions in a new light. Munich 2004, ISBN 3-7774-2455-2 .

- Volker Rattemeyer (Ed.): Jawlensky in Wiesbaden. Paintings and graphic works in the art collection of the Wiesbaden Museum. Museum Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden 2007, ISBN 978-3-89258-072-0 (German-Russian).

- Bernd Fäthke: Werefkin and Jawlensky with their son Andreas in the “Murnauer Zeit”. In: 1908–2008, 100 Years Ago, Kandinsky, Münter, Jawlensky, Werefkin in Murnau. Exhibition catalog. Murnau 2008, p. 31 ff.

- Brigitte Roßbeck : Marianne von Werefkin. The Russian from the Blue Rider's circle. Munich 2010.

- Bernd Fäthke: Alexej Jawlensky. In: Expressionismus auf dem Darß, Aufbruch 1911, Erich Heckel, Marianne von Werefkin, Alexej Jawlensky. Exhibition catalog, Fischerhude 2011, p. 56 ff.

- Brigitte Salmen (Ed.): "... these tender, spirited fantasies ..." The painters of the "Blauer Reiter" and Japan. Exhibition catalog. Murnau Castle Museum 2011, ISBN 978-3-932276-39-2 .

- Bernd Fäthke: Alexej Jawlensky. Heads etched and painted. The Wiesbaden years. Exhibition catalog. Draheim, Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-00-037815-7 .

- Erik Stephan (Ed.): "I work for myself, only for myself and my God." Alexej von Jawlensky. Exhibition catalog. Jena Art Collection, Jena 2012, ISBN 978-3-942176-70-5 .

- “In close friendship.” Alexej Jawlensky, Paul and Lily Klee, Marianne Werefkin, The Correspondence. Edited by Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, and by Stefan Frey. Zurich 2013, ISBN 978-3-909252-14-5 .

- Ingrid Mössinger, Thomas Bauer-Friedrich (ed.): Jawlensky. Newly seen. Exhibition catalog. Sandstein Verlag, Dresden 2013, ISBN 978-3-95498-059-8 .

- Roman Zieglgänsberger (Ed. On behalf of the Museum Wiesbaden and the Kunsthalle Emden): Horizont Jawlensky. Alexej von Jawlensky as reflected in his artistic encounters 1900–1914. Exhibition catalog. Hirmer, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-7774-2172-8 .

- Roman Zieglgänsberger: "It's true, the summer is always horrible there" - Alexej von Jawlensky and his contribution to the Blue Rider. In: Blue House and Yellow Sound. Wassily Kandinsky and Alexej Jawlensky in Murnau. Exhibition catalog. Murnau Castle Museum 2014, pp. 39–51.

- Bernd Fäthke: Marianne Werefkin - “the blue rider”. In: Marianne Werefkin, From the Blue Rider to the Great Bear. Exhibition catalog. Municipal Gallery Bietigheim-Bissingen 2014, ISBN 978-3-927877-82-5 , p. 24 ff.

- Vivian Endicott Barnett (Ed.): Alexej Jawlensky. Exhibition catalog. Neue Galerie - Museum for German and Austrian Art, New York, Munich / London / New York 2017.

- Roman Zieglgänsberger: turning point. Alexej von Jawlensky between Kandinsky, Marc, and Macke in the Kirchhoff Collection. In: Roman Zieglgänsberger, Sibylle Discher (ed.): The garden of the avant-garde. Heinrich Kirchhoff: A collector of Jawlensky, Klee, Nolde ... exhibition catalog. Museum Wiesbaden 2017/2018, Petersberg 2017, pp. 287–302.

- Christian Philipsen, Angelica Affentranger-Kirchrath, Thomas Bauer-Friedrich (eds.): Alexej von Jawlensky / Georges Rouault. Seeing with your eyes closed. Exhibition catalog. Moritzburg Art Museum Halle (Saale), Petersberg 2017.

- Benno Tempel, Doede Hardeman, Daniel Koep (eds.): Alexej von Jawlensky. Expressionisme en devotie / Expressionism and Devotion . Exhibition catalog. Gemeentemuseum Den Haag 2018/2019, Zwolle 2018.

- Roman Zieglgänsberger, Annegret Hoberg , Matthias Mühling (eds.): Lebensmenschen - Alexej von Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin , exhibition catalog. Municipal gallery in the Lenbachhaus and Kunstbau, Munich / Museum Wiesbaden, Munich a. a. 2019/2020, ISBN 978-3-7913-5933-5 .

Web links

(en)

- Literature by and about Alexej von Jawlensky in the catalog of the German National Library

- Alexej von Jawlensky Archive

- Angelika Affentranger, Paola von Wyss-Giacosa: Jawlensky, Alexej von. In: Sikart

- Materials by and about Alexej Jawlensky in the documenta archive

- Alexej von Jawlensky on artnet

- On Alexej von Jawlensky's late work on Schirn Magazin

- Alexej von Jawlensky, "I am absorbed in you ..." , Irina Dewjatjarowa, Russkoje Iskusstwo, No. 3, 2005 (Russian)

Individual evidence

- ↑ The Julian date of March 13th corresponded to the Gregorian date of March 25th in the 19th century , but from 1900 it was March 26th. This is why the last date is often incorrectly given as Alexej Jawlensky's date of birth.

- ↑ The date of birth March 13, 1865 is given in the application for admission to the Petersburg Art Academy in 1890, see: Anton Tuchta: The origins of creativity in a small country (A few pages from the life of the artist Alexej Jawlensky). Entry into science: reports of the IV. Interregional research conference for students in the southwestern part of Tver Oblast ( Memento of January 12, 2011 in the Internet Archive ). Nelidowo , February 8, 2010, pp. 89-93 (Russian). The same date of birth appears from his official certificate of December 31, 1894. It is in the Russian Military History Archive in Moscow. We owe our knowledge of this document to the Russian art historian Irina Devyatjarowa, Omsk Museum. Private archive for expressionist painting, Wiesbaden.

- ↑ a b Jawlensky himself always refers in his memoirs to the year of birth 1864. Alexej von Jawlensky, 1937, in: Memories, quoted. n. Clemens Weiler: Jawlensky, heads, faces, meditations. Hanau 1970.

- ↑ In July 1934 Jawlensky received German citizenship. Compare: Tayfun Belgin: Alexej von Jawlensky, An artist biography. Heidelberg 1998, p. 130.

- ↑ Jelena Hahl-Fontaine: Jawlensky and Russia. The time at the academy and the artist's actual year of birth. In exh. Cat .: Alexej von Jawlensky, The watercolors found again, The eye is the judge, Watercolors-paintings-drawings. Museum Folkwang, Essen 1998, p. 40

- ↑ Hans Hildebrandt: The art of the 19th and 20th centuries, Wildpark-Potsdam 1924, p. 375

- ↑ Clemens Weiler: Alexej Jawlensky. Cologne 1959, p. 13

- ↑ Maria Jawlensky, Lucia Pieroni-Jawlensky and Angelica Jawlensky (ed.): Alexej von Jawlensky, catalog raisonné of the oilpaintings. Vol. 1, Munich 1991, p. 11

- ↑ Jelena Hahl-Fontaine: Jawlensky and Russia. The time at the academy and the artist's actual year of birth. In exh. Cat .: Alexej von Jawlensky, The watercolors found again, The eye is the judge, Watercolors-paintings-drawings. Museum Folkwang, Essen 1998, p. 40

- ↑ Jelena Hahl-Fontaine: Jawlensky and Russia. The time at the academy and the artist's actual year of birth. In exh. Cat .: Alexej von Jawlensky, The watercolors found again, The eye is the judge, Watercolors-paintings-drawings. Museum Folkwang, Essen 1998, p. 38

- ↑ Jelena Hahl-Fontaine: Jawlensky and Russia. The time at the academy and the artist's actual year of birth. In exh. Cat .: Alexej von Jawlensky, The watercolors found again, The eye is the judge, watercolors-painting-drawings. Museum Folkwang, Essen 1998, p. 61, note 7.

- ↑ Volker Rattemeyer (Ed.): Biography Alexej von Jawlensky. In exh. Cat .: Jawlensky, my dear Galka! Museum Wiesbaden, Wiesbaden 2004, p. 272

- ^ Annegret Hoberg and Roman Zieglgänsberger: A couple biography. Jawlensky and Werefkin - Common and Separate Ways. In exh. Cat .: Lebensmenschen - Alexej von Jawlensky and Marianne von Werefkin. Municipal gallery in the Lenbachhaus and Kunstbau Munich, Munich 2019, p. 20

- ↑ Alexej Jawlensky: Memorabilia In: Clemens Weiler (ed.), Alexej Jawlensky, Heads-Face-Meditations , Hanau 1970, p. 95

- ↑ Jehudo Epstein: My way from east to west, memories. Stuttgart 1929, p. 8 f

- ↑ Jawlensky himself writes in his memoirs that he lost his father at the age of 18. Alexej von Jawlensky, 1937, in: Memories, quoted. n. Clemens Weiler: Jawlensky, heads, faces, meditations. Hanau 1970, p. 99.

- ↑ There are sometimes irritations with regard to Helene Nesnakomoff's date of birth. The reason for this is an identity exchange that Marianne von Werefkin had carried out in order to protect Jawlensky from possible criminal prosecution, as Helene was only 16 when their son was born. After returning from Latvia, she registered Helene in Munich with the year and place of birth of her sister Maria, who was four years older than her (Clemens Weiler: Marianne Werefkin, letters to an unknown 1901–1905. Cologne 1960, p. 37 f., And: Bernd Fäthke: Marianne Werefkin. Munich 2001, p. 55 f., As well as: Brigitte Roßbeck: Marianne von Werefkin. The Russian woman from the circle of the blue rider. Munich 2010 (2), p. 76 f.). On Helene's tombstone and in some publications by Jawlensky's descendants, however, the date of birth “officially” registered in 1902 is shown. Image of tombstone with dates , findagrave.com, accessed June 17, 2013

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: In the run-up to Expressionism, Anton Ažbe and painting in Munich and Paris. Wiesbaden 1988.

- ^ Roman Zieglgänsberger: Horizont Jawlensky. Alexej von Jawlensky as reflected in his artistic encounters 1900–1914. Pp. 33-36.

- ↑ Brigitte Roßbeck: Marianne von Werefkin, The Russian woman from the circle of the Blue Rider. Munich 2010, pp. 87–91.

- ^ Marianne Werefkin: Lettres à un Inconnu. Fondazione Marianne Werefkin , Vol. II, p. 273.

- ↑ Alexej Jawlensky: Memoirs. In: Clemens Weiler (ed.): Alexej Jawlensky, Heads - Faces - Meditations. Hanau 1970, p. 110 f. Possibly Jawlensky's error can be explained by the fact that he did not begin to dictate his memoirs until 1937/1938 - thirty years after the trip to France that was so important for him and for art history.

- ^ Roman Zieglgänsberger ,: Horizont Jawlensky. Alexej von Jawlensky as reflected in his artistic encounters 1900–1914. Pp. 41-43.

- ↑ Tayfun Belgin: Alexej von Jawlensky, An artist biography. Heidelberg 1998, p. 52 f.

- ↑ Armin Second: “Harmonies pervaded by dissonances”, On Jawlensky's time in Munich 1896–1914. In: exhib. Cat .: Alexej von Jawlensky, Travels - Friends - Changes. Museum am Ostwall, Dortmund 1998, p. 43

- ↑ Langejan: A painter letter I. In: Christian art , 7 (1910/1911), pp 336-338.

- ^ Hugo Troendle: Paul Sérusier and the school of Pont-Aven. In: The artwork, Baden-Baden 1952, p. 21.

- ^ Roman Zieglgänsberger: Horizont Jawlensky. Alexej von Jawlensky as reflected in his artistic encounters 1900–1914. Pp. 43-48; as well as there: Annegret Kehrbaum: depicting the invisible in the visible. Alexej von Jawlensky's encounter with the "Synthèse" of Paul Gauguin. Pp. 208-228.

- ^ Wladislawa Jaworska: Paul Gauguin et l'école de Pont-Aven. Neuchâtel 1971, p. 119 f.

- ↑ Annegret Hoberg, Titia Hoffmeister, Karl-Heinz Meißner, anthology, in exh. Cat .: The Blue Rider and the New Image. From the “New Munich Artists' Association” to the “Blue Rider”. Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich 1999, p. 29.

- ^ Wassily Kandinsky / Franz Marc, correspondence. Edited by Klaus Lankheit. Munich 1983, p. 29.

- ^ Annegret Hoberg: "New Artists' Association Munich" and "Blauer Reiter". In: exhib. Cat .: The Blue Rider and the New Image. From the “New Munich Artists' Association” to the “Blue Rider”. Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich 1999, p. 35.

- ^ Annegret Hoberg: Maria Marc, Life and Work 1876–1955. Exhib. Cat .: City Galerie im Lenbachhaus, Munich 1995, p. 49.

- ↑ Gisela Kleine: Gabriele Münter and Wassily Kandinsky, biography of a couple. Frankfurt am Min 1990, p. 365.

- ^ Franz Marc: Letters, Writings and Notes. Leipzig / Weimar 1980, p. 39.

- ↑ Wassily Kandinsky: About the spiritual in art, especially in painting. Munich 1912, p. 83 f.

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Marianne Werefkin. Munich 2001, p. 99 ff. The majority of the artist's artistic and literary estate is kept in the Fondazione Marianne Werefkin .

- ↑ Klaus Lankheit: The Blue Rider - Precisions. In: exhib. Cat .: Kunstmuseum Bern 1986, p. 225.

- ↑ Véronique Serrano: Experience modern et conviction classique. in: exhib. Cat .: Pierre Girieud et l'expérience de la modernité, 1900–1912. Musée Cantini, Marseille 1996, p. 117.

- ^ Annegret Hoberg: Wassily Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter in Murnau and Kochel 1902–1914, letters and memories. Munich 1994, p. 123.

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Staging a crash, news from the "Blue Rider". In: Weltkunst , Volume 70, No. 13, November 1, 2000, p. 2218 f.

- ↑ Wassily Kandinsky: Our friendship. Memories of Franz Marc. In: Klaus Lankheit: Franz Marc in the judgment of his time, texts and perspectives. Cologne 1960, p. 48.

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Alexej Jawlensky, heads etched and painted, The Wiesbaden years. Galerie Draheim, Wiesbaden 2012, ISBN 978-3-00-037815-7 , p. 56 ff, fig. 54 and 55.

- ↑ Otto Fischer: The new picture. Publication of the Neue Künstlervereinigung München, Munich 1912.

- ^ Original in the Munich City Archives

- ↑ Journal de Bordighera et List des Étrangers, No. 15, February 12, 1914, p. 7

- ↑ Alexej Jawlensky to Galka Scheyer, letter of January 25, 1920, private archive for expressionist painting, Wiesbaden

- ↑ Jawlensky and Scheyer only used the term since the 1930s.

- ↑ LZ: Russia, The new works Alex. v. Jawlenskys. In: Der Ararat, No. 8, July 1920, p. 73.

- ↑ Detlev Rosenbach: Alexej von Jawlensky, life and graphic works. Hannover 1985, ill.p. 149, 151, 153, 155.

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: The Jawlensky case. Original - copy - forgery, part II. In: Weltkunst from August 15, 1998, p. 1505, fig. 4-13.

- ↑ Alexander Hildebrand: Alexej Jawlensky in Wiesbaden. Reflexes on Life and Work (1921–1941). In: Exh. Cat .: Jawlensky's Japanese woodcut collection. A fairytale discovery. Edition of the Administration of State Palaces and Gardens, Bad Homburg vdH, No. 2, 1992, p. 56 ff

- ↑ H. Zeidler: "Memories of my sick hands", life and medical history of the painter Alexej von Jawlensky. In: Zeitschrift für Rheumatologie, Vol. 70, H. 4, June 2011, p. 340.

- ↑ The stay in Bad Wörishofen is marked by two paintings - see: Maria Jawlensky, Lucia Pieroni-Jawlensky, Angelica Jawlensky (eds.): Alexej von Jawlensky, Catalog Raisonné of the oil-paintings, vol. 2. Munich 1992, no. 1281 and 1282, p. 408 - and an unpublished drawing attested.

- ↑ Alexej von Jawlensky (from: lemo , accessed on February 6, 2019)

- ↑ Alexej Jawlensky to Galka Scheyer, February 23, 1935, private archive for expressionist painting, Wiesbaden

- ↑ kuenstlerbund.de: Ordinary members of the German Association of Artists since it was founded in 1903 / Jawlensky, Alexej von ( Memento from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) (accessed on January 18, 2016)

- ↑ 1936 forbidden pictures , exhibition catalog for the 34th annual exhibition of the DKB in Bonn, Deutscher Künstlerbund, Berlin 1986, p. 46f.

- ↑ Michael Semff: Variations - Meditations, on Jawlensky's late work. In: exhib. Cat .: Picture cycles, testimonies to ostracized art in Germany 1933–1945. P. 19 f.

- ↑ Marina Vershevskaya: Tombs Tell History, The Russian Orthodox Church of St. Elisabeth and her cemetery in Wiesbaden. Wiesbaden 2007, p. 107 f.

- ^ Jawlensky: Das Artwork II , 1948, p. 51

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Von Werefkins and Jawlensky's weakness for Japanese art. In exh. Cat .: "... the tender, spirited fantasies ...", the painters of the "Blue Rider" and Japan. Murnau Castle Museum 2011, p. 106 ff

- ↑ Petra Hinz: Japonism in graphics, drawing and painting in the German-speaking countries around 1900. Diss. Ludwig Maximilians University Munich 1982, p. 116.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Maria Jawlensky, Lucia Pieroni-Jawlensky, Angelica Jawlensky (eds.): Alexej von Jawlensky, Catalog Raisonné of the oil-paintings.

- ↑ Exhib. Cat .: Jawlensky's Japanese woodcut collection. A fairytale discovery. Edition of the Administration of State Palaces and Gardens, Bad Homburg vdH, No. 2, 1992.

- ↑ Ursula Perucchi-Petri: The Nabis and Japan. Munich 1976, fig. 4, 8, 23, 33, 37, 104, 117, 123, 126, 130, 131, 136.

- ^ Maria Jawlensky, Lucia Pieroni-Jawlensky, Angelica Jawlensky (eds.): Alexej von Jawlensky, Catalog Raisonné of the oil-paintings, Vol. 1. Munich 1991, No. 250.

- ^ Elisabeth Erdmann-Macke: Memories of August Macke. Frankfurt 1987, p. 240 f.

- ↑ Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharow: Vincent van Gogh and the Birth of Cloisonism. Exhib. Cat .: Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto 1981, p. 114 f.

- ↑ Whether Jawlensky owned the original Oiran von Eisen sheet can unfortunately no longer be reconstructed. However, in his collection, which is still in existence today, a comparable print of iron can be proven, see: Ildikó Klein-Bednay: Jawlensky's Japanese woodcut collection. In: exhib. Cat .: Jawlensky's Japanese woodcut collection. A fairytale discovery. Edition of the Administration of State Palaces and Gardens, Bad Homburg vdH, No. 2, 1992, p. 143, No. 68.

- ↑ Today Jawlensky's Japanese woodcut collection is in the Gabriele Münter and Johannes Eichner Foundation of the Lenbachhaus in Munich .

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Von Werefkins and Jawlensky's weakness for Japanese art. In: exhib. Cat .: "... the tender, spirited fantasies ..." The painters of the "Blauer Reiter" and Japan. Murnau Castle Museum, 2011, p. 124 f.

- ↑ Friedrich B. Schwan: Handbook of Japanese Woodcut - Backgrounds, Techniques, Themes and Motifs. Munich 2003, p. 462.

- ↑ Ildikó small Bednay: Jawlensky Japanese woodcut collection. In: exhib. Cat .: Jawlensky's Japanese woodcut collection. A fairytale discovery. Edition of the Administration of State Palaces and Gardens, Bad Homburg vdH, No. 2, 1992, p. 145 f.

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Der Held vom Kabuki-Theater - Alexej Jawlensky collected Japanese woodcuts… In: Weltkunst, 2006, issue 6, p. 16 ff.

- ↑ Thomas Leims: Kabuki - text versus acting. In: Classical Theater Forms of Japan, Introductions to Noo, Bunraku and Kabuki. Edited by the Japanese Cultural Institute Cologne, Cologne / Vienna 1983, p. 75.

- ↑ Christ heads are a special topos of heads. This emerges from a letter from Jawlensky to Galka Scheyer dated January 25, 1920: “I have been working a lot recently. I made 12 heads. 4 of them are good and something new there. It's strange that I haven't made a Christ head now. I felt the need to do something different. ”See: Maria Jawlensky, Lucia Pieroni-Jawlensky, Angelica Jawlensky (eds.): Alexej von Jawlensky, Catalog Raisonné of the oil-paintings, Vol. 2. Munich 1992, p. 21 f. Christ heads can be recognized by the spiked shapes on and above the forehead, which sometimes cross over each other several times. They symbolize the crown of thorns of Christ. Jawlensky's Catalog Raisonné lists 64 such Christ heads from 1917 to 1936.

- ↑ Stefan Koldehoff , Tobias Timm : False pictures - real money. The counterfeit coup of the century - and who earned everything from it. Berlin 2012; Helene Beltracchi, Wolfgang Beltracchi: Inclusion with angels. Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek 2014, ISBN 978-3-498-04498-5 .

- ↑ Karin von Maur : Vigorously grown early work. The ladies of the Jawlensky family have won: the new catalog of works is here. Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, June 6, 1992

- ↑ Alexander Hildebrand: Jawlensky's wonderful image multiplication, To the first volume of the new catalog of works. In: Wiesbadener Leben, August 1992, p. 4 f

- ↑ Alexander Hildebrand: In search of the true work - Jawlensky's "black series". In: Wiesbadener Leben, September 1992, p. 26 f. Klaus Ahrens, Günter Handlögten: Real money for fake art. Remchingen, 1992, p. 181 f.

- ↑ Klaus Ahrens, Günter Handlögten: Real money for false art. Remchingen, 1992, p. 181 f.

- ↑ Stefan Koldehoff: Revision of Classical Modernism, Essential Catalogs of Works appeared again this year. In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung of September 28, 1996.

- ↑ Susanna Partsch: Tatort art, about forgeries, fraudsters and deceit. Munich 2010, p. 179.

- ↑ Christian Herchenröder: Problematic fodder for the market - The Jawlensky case: Controversial paintings and watercolors pollute the market. In: Handelsblatt, 28./29. April 1995.

- ↑ Stefan Koldehoff, Tobias Timm: False pictures - real money. The counterfeit coup of the century - and who earned everything from it. Berlin 2012, p. 40.

- ↑ Exhib. Cat .: Alexej von Jawlensky, The re-found watercolors. The eye is the judge, watercolors-paintings-drawings. Museum Folkwang, Essen 1998

- ↑ The judge's eye was blind. In: welt.de . February 3, 1998, accessed October 7, 2018 .

- ↑ Werner Fuld: The lexicon of forgeries - forgeries, lies and conspiracies from art, history, science and literature. Frankfurt 1999, p. 127.

- ↑ Isabell Fechter: The Jawlensky scandal, retrospectives. In: Weltkunst, March 15, 1998, p. 560 f.

- ↑ Jörg Bittner: The Jawlensky case, Why the “Dimitri” bundle cannot be genuine. Copied from publications fresh on the market. In: Handelsblatt, 6./7. February 1998

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento from May 4, 2014 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ https://www.fr.de/kultur/jawlensky-faelschungen-emden-11297454.html

- ↑ http://www.on-online.de/-news/artikel/118470/Kunsthalle-Emden-nnahm-zwei-Faelschungen-aus-der-Sammlung

- ↑ Johannes Eichner: Kandinsky and Gabriele Münter, From the origins of modern art . Munich 1957, p. 88.

- ↑ Jelena Hahl-Fontaine: Jawlensky and Russia. in exh. Cat .: Alexej von Jawlensky, The watercolors found again, The eye is the judge, Watercolors - paintings - drawings. Museum Folkwang, Essen 1998, ill. P. 45.

- ↑ Brigitte Salmen, Introduction, in exhib. Cat .: Marianne von Werefkin in Murnau. Art and theory, role models and artist friends. Murnau 2002, cat.no.6a and 118, illus. P. 7.

- ↑ Helene Nesnakomoff

- ↑ Willibrord Verkade: The drive towards perfection, memories of a painter monk. Freiburg 1931, pp. 169, 172.

- ↑ f / http: //www.jawlensky.ch/inhalt/bio.htm Biography ( Memento from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Tomb in the Russian cemetery in Wiesbaden

- ↑ Helene Nesnakomoff

- ↑ Maria Jawlensky, Lucia Pieroni-Jawlensky, Angelica Jawlensky (eds.): Alexej von Jawlensky, Catalog Raisonné . Volume 1-4. Munich 1991–1998.

- ↑ Georg-W. Költzsch, Michael Bockemühl (ed.): Alexej von Jawlensky, The re-found watercolors. The eye is the judge, watercolors - paintings - drawings. Exhib. Cat .: Museum Folkwang, Essen 1998.

- ↑ The main events were summarized in a lecture by Isabell Fechter: The Jawlensky scandal, retrospectives. In: Weltkunst March 15, 1998, p. 560 f.

- ↑ A. v. Jawlensky Archive (ed.): Series Image and Science - Research contributions to the life and work of Alexej von Jawlensky. So far 3 volumes. Locarno 2003, 2006 and 2009.

- ↑ Ida Harth zur Nieden: My dear Andreas. In: To my beloved Andreas on the 70th birthday. Hanau 1972, no p.

- ↑ a b Irene Netta, Ursula Keltz: 75 years of the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus and Kunstbau Munich . Ed .: Helmut Friedel. Self-published by the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus and Kunstbau, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-88645-157-7 , p. 201 .

- ↑ us [Bruno Russ]: On the pleasure and profit of having to look at only a few pictures, replacement for Jawlensky: Jawlensky from private collectors. In: Wiesbadener Kurier, Friday, March 4, 1983, p. 9; CGK: Pictures not only as a substitute, exhibition by Wiesbaden art collectors around Jawlensky in the museum. In: Wiesbadener Tagblatt, March 4, 1983, p. 7.

- ^ Anne Stephan-Chlustin: Jawlensky's drawings - documents on his work. An important exhibition / stylistic development, personal environment. In: Wiesbadener Kurier, December 16, 1983, p. 18; Mathias Heiny: Counter-concept with drawings and documents. Museum Wiesbaden is showing for the first time an exhibition dedicated to the draftsman Jawlensky. 17./18. December 1983, p. 19.

- ↑ To the exhibition Seeing with your eyes closed. ( Memento from October 23, 2018 in the Internet Archive ) In: stiftung-moritzburg.de, accessed on October 23, 2018

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Jawlensky, Alexej von |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Jawlenski, Alexei Georgievich; Явленский, Алексей Георгиевич (Russian); Javlenskij, Alexej Georgievič (scientific transliteration) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German-Russian artist of expressionism |

| DATE OF BIRTH | March 25, 1864 or March 25, 1865 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Torzok |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 15, 1941 |

| Place of death | Wiesbaden |