Alexander Sacharoff

Alexander Sacharoff ( Russian Александр Сахаров , in English or French spelling also Sakharov or Sakharoff , * July 14th / May 26th, 1886 greg. As Alexander Zuckermann in Mariupol ( Russian Empire ); † September 25, 1963 in Siena ) was a Dancer , choreographer , painter and teacher .

Together with his artistic partner Clotilde von Derp (1892–1974, born as Clotilde Margarete Anna Edle von der Planitz ), whom he married in 1919, Sacharoff created his own form of modern dance, which he called "abstract pantomime ". The couple also designed their own costumes, famous for their sophistication. Alexander Sacharoff and Clotilde von Derp are considered one of the most famous couples in the history of dance.

Life

Alexander Sacharoff was the last of seven sons of Maria Polianskaja and Simon Zuckermann. In 1898 Alexander moved to Saint Petersburg to attend secondary school there.

During his law and painting studies in Paris from 1903 to 1905, Sacharoff attended a performance by the actress Sarah Bernhardt , where she danced a minuet . Sacharoff then decided to become a dancer. In 1905 Sacharoff went to Munich and initially took lessons there - in classical ballet as well as in acrobatics lessons in the Schumann circus .

In 1909 Alexander Sacharoff joined the Neue Künstlervereinigung München and worked with the Russian painter Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) and the Russian composer Thomas von Hartmann on the realization of a synaesthetic work of art.

On June 2, 1910, Alexander Sacharoff made his debut as a solo dancer in the Munich Tonhalle in a piece inspired by mythological motifs and Renaissance painting. Sacharoff is probably the first male free dancer in Europe. In the same year, Sacharoff's future partner and partner Clotilde von Derp made her debut . At that time, for example, Von Derp, under the direction of Max Reinhardt , danced the first elf in Midsummer Night's Dream at the Munich Art Theater. In the following years, Sacharoff performed as a solo dancer all over Germany. He also performed with Rita Sacchetto . In 1912 Sacharoff returned to Russia for a short time.

In 1913, Alexander Sacharoff and Clotilde von Derp met at the Munich press ball. Sacharoff formulated their common artistic credo in 1943 in his book Réflexions sur la danse et la musique (Viau, Buenos Aires 1943) as follows: “... Clotilde Sacharoff and I did not dance with music or accompanied by music: we danced music. We made the music visible by expressing with the means of movement what the composer has expressed with the means of sound ... Nothing other than the states of mind, impressions, sensations that the composer experienced and transformed into sound through his art ... Our goal was to to translate the meaning expressed by the sound music into the music of movement. "

As an "enemy alien", Sacharoff had to leave Germany at the start of the war in 1914. Therefore, the couple went to Switzerland to Lausanne , where Clotilde ballet lessons with Enrico Cecchetti took.

During the war, Sacharoff and von Derp made numerous appearances in Switzerland . In 1919 the Zurich Kunsthaus showed collages by Alexander Sacharoff. Also in Zurich , Clotilde von Derp and Alexander Sacharoff married on July 25, 1919. Edith McCormick Rockefeller financed their first tour in the United States.

On February 17, 1920, the Sacharoffs made their debut in the New York Metropolitan at a benefit gala. On April 6th, she performed at the New York Globe Theater .

In 1921 the couple performed at the Paris Théâtre des Champs-Elysées . In 1922 it made its first appearance in London at the Coliseum . The Sacharoffs settled in Paris.

In the 1920s, the Sacharoffs toured Europe and the Middle East to perform. In 1930 there was a first tour in the Far East with performances in Shanghai , Beijing , Osaka , Tokyo and Saigon , which was followed by a second tour in 1934 with performances in the Republic of China , the Japanese Empire and Java . Immediately after their return trip, the Sacharoffs went on tour to Canada and the United States. Tours through South America with performances in Havana , São Paulo , Montevideo and Buenos Aires (Teatro Colon) as well as many European countries followed.

The Sacharoffs saw the beginning of the Second World War in Portugal. Unable to return to their Paris apartment, they settled in Lisbon. In 1941 the couple emigrated to South America and separated there. Alexander Sacharoff moved into an apartment in Buenos Aires, Clotilde went to Montevideo. However, they continued to meet for joint dance projects.

In 1948 Clotilde first returned to Europe, and Alexander Sacharoff later followed her to Paris. Both performed together again at the Paris Théâtre des Champs-Elysées. In 1952 the Sacharoffs moved to Rome and began teaching at the Accademia Musicale Chigiana in Siena.

In 1954 the Sacharoffs gave their last performance in the Roman Teatro Eliseo. Alexander Sacharoff mainly designed costumes, and the couple also gave summer courses in Siena. In 1955, the Galleria delle Carrozze in Rome presented Sacharoff's collages, stage and costume designs in a second exhibition.

Alexander Sacharoff died in Siena on September 25, 1963. Sacharoff is buried with his wife, who died in 1974, on the Cimitero Acattolico in Rome .

Dance performance

Sacharoff and Japonism

It used to be thought that Sacharoff had designed his new type of expressive dance essentially based on the ancient world of the Greeks. However, various stylistic and motivic elements in Werefkins and Jawlensky's paintings, drawings and gouaches, as well as his own self-portrait in dance pose , make it clear that the dancer was not only enthusiastic about the general Japonism of his time, but also about a profound knowledge of Japanese Theater decreed.

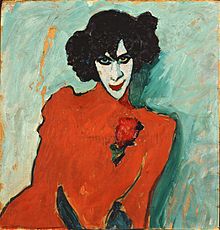

The earliest indication of his sympathy for Japanese culture is the acquisition of a still life by Jawlensky from around 1904, which has a Japanese doll against a red background. Otherwise, there are many details in Werefkins and Jawlensky's Sacharoff depictions that illustrate how open-minded he was to Japanese fashion at the time. The best known are the poster-like portraits that show the dancer in a make-up mask and in a Mie pose , which can be found in the Lenbachhaus in Munich , the State Gallery in Stuttgart , the Asconesian Fondazione Marianne Werefkin and the Wiesbaden Museum .

Sacharoff borrowed z. B. Kimonos from Japanese woodcut art for his stage appearances. Particularly striking were hauling clothes that were behind much longer than floor-length tailored. The ends of the clothes accumulate on the floor with a "bulge" and were dragged afterwards. Jawlensky's depiction of Sacharoff, but also Sacharoff's self-portrait in a dance pose, shows this motif as a rudimentary "dragline" that the artists have copied from Japanese woodcuts on the "outer kimono" - uchikake , which is worn like an open coat over the undergarment, Kosode to have. In both cases it was combined with another typically Japanese motif, namely a stowage fold in the fabric on the front part of the kimono from which the tip of the foot protrudes. This is the “short step” with a slightly “bent posture of the upper body”, which is characteristic of Japanese art and is often found in its woodcuts.

For Sacharoff, who designed his style of dance less as pure sequences of movements than as sequences of images, his posture in various vertical, horizontal and inclined positions played a decisive role. Again and again one comes across derivations from Japanese. An abundance of his arms, hands and legs appear unusual and strange. If z. B. Sacharoff at the moment of the Mie pose of standstill, a kind of "not moving", with a quick, short movement stretching his right hand with outstretched fingers signalingly out of the robe, one involuntarily has the woodcut of the actor "Otani Oniji" of Sharaku in mind. Capricious hand and finger positions or the pathetic handling of a fan appear as recourse to special characteristics of Japanese acting in works by Kitagawa Utamaro , Katsushika Hokusai or Utagawa Kunisada and others. They indicate that Sacharoff's dances were interspersed with Japanese bonds.

literature

- Hans Brandenburg: Alexander Sacharoff (1913) . In: Hans Brandenburg: The modern dance . Munich 1913, pp. 121-130.

- Frank-Manuel Peter , Rainer Stamm (ed.): The Sacharoffs - Two dancers from the circle of the Blue Rider. Book accompanying the exhibition of the same name in the German Dance Archive in Cologne and in the Villa Stuck in Munich. Wienand Verlag, Cologne 2002, ISBN 3-87909-792-5 .

- Frank-Manuel Peter: Sacharoff, Alexander. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 22, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-428-11203-2 , p. 322 f. ( Digitized version ).

- Brigitte Salmen (ed.): "... the tender, spirited fantasies ...", the painters of the "Blue Rider" and Japan . Exhibition catalog. Murnau Castle Museum, 2011, ISBN 978-3-932276-39-2 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Alexander Sacharoff in the catalog of the German National Library

- Sacharoff Archive - Information on the Sacharoff Archive in the German Dance Archive Cologne

- Papers of Alexandre and Clotilde Sakharoff ( September 2, 2006 memento in the Internet Archive ) - Guide to the holdings of the Houghton Library, Harvard College Library

- Contemporary texts on Alexander Sacharoff and Clotilde von Derp (1910–1914)

- Horst Koegler on the book "The Sacharoffs" (2002)

- Horst Koegler on the exhibition "The Sacharoffs - Two Dancers from the Circle of the Blue Rider" (2002/2003)

Individual evidence

- ^ Rainer Stamm: Alexander Sacharoff - Fine arts and dance . In: The Sacharoffs, two dancers from the circle of the Blue Rider . Exhibition catalog. Paula Modersohn-Becker Museum, Bremen 2002, p. 11 ff

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Von Werefkins and Jawlensky's weakness for Japanese art . In: "... the tender, spirited fantasies ...", the painters of the "Blue Rider" and Japan . Exhibition catalog. Murnau Castle Museum, 2011, Fig. 35, p. 119

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: The hero from the Kabuki theater - Alexej Jawlensky collected Japanese woodcuts . In: Weltkunst , 06/2006, p. 16 ff.

- ^ Maria Jawlensky, Lucia Pieroni-Jawlensky, Angelica Jawlensky (eds.): Alexej von Jawlensky, Catalog Raisonné of the oil-paintings , vol. 1. Munich 1991, no. 79, p. 82

- ↑ Thomas Leims: The Continuity of Form - Problems of Japanese Theater History . In: Classical Theater Forms of Japan, Introductions to Noo, Buntraku and Kabuki . Japanese Cultural Institute Cologne, Cologne 1983, p. 2

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Marianne Werefkin . Munich 2001, p. 133 ff

- ^ Siegfried Wichmann : Japonism, East Asia-Europe, Encounters in the Art of the 19th and 20th Century . Herrsching 1980, p. 16

- ↑ Ildikó small Bednay: Jawlensky Japanese woodcut collection . In: Jawlensky's Japanese woodcut collection. A fairytale discovery . Exhibition catalog. Edition of the Administration of State Palaces and Gardens, Bad Homburg vdH, 1992, No. 2, p. 119

- ↑ Friedrich B. Schwan: Handbook of Japanese Woodcut - Backgrounds, Techniques, Themes and Motifs . Munich 2003, p. 736

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Von Werefkins and Jawlensky's weakness for Japanese art . In: "... the tender, spirited fantasies ...", the painters of the "Blue Rider" and Japan . Exhibition catalog. Murnau Castle Museum, 2011, p. 118, Figs. 30 and 32

- ^ Siegfried Wichmann: Japonism, East Asia-Europe, Encounters in the Art of the 19th and 20th Century . Herrsching 1980, p. 36

- ^ Hans Brandenburg: The modern dance . Munich 1921, p. 145 ff.

- ^ Thomas Leims: Kabuki - woodcut - Japonism, Japonica in the theater collection of the Austrian National Library . Vienna / Cologne / Graz 1983, p. 12

- ↑ Bernd Fäthke: Alexej Jawlensky, drawing-graphic documents . Exhibition catalog. Museum Wiesbaden 1983, pp. 36–40, figs. 37–45

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Sacharoff, Alexander |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Zuckermann, Alexander |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Russian-Jewish dancer |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 26, 1886 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Mariupol |

| DATE OF DEATH | September 25, 1963 |

| Place of death | Siena , Italy |