Utagawa School

The Utagawa School ( Japanese 歌 川 派 , Utagawa-ha ) was a group of Japanese artists who, as the dominant school , drew designs for color and woodblock prints in the style of ukiyo-e during the late Edo period to the end of the Meiji period and some of them were also active as painters.

School beginnings

The Utagawa School originated in Edo , today's Tokyo , in the last decades of the 18th century and is named after the Udagawachō district, where its founder, Toyoharu , settled in Edo. Toyoharu came to Edo in 1763 and gained his reputation as a woodcut artist through his further development of perspective landscape printing, which goes back to European influences. His most important pupil was Toyokuni I , who made actor prints more realistic and therefore more realistic than the representatives of the Torii and Katsukawa schools . By the end of the 18th century, Toyokuni had already gathered numerous students and until his death in 1825 he trained many of the most important artists of the Japanese color and woodcut of the 19th century, including Kunimasa I , Kuniyasu , Kunisada I and Kuniyoshi . At Toyokuni's classmate, Toyohiro , Hiroshige I finally met , who and his students mastered Japanese landscape printing from the mid-1830s.

Development and fields of activity

Over the generations, the school had almost 400 members. Many of them are only known through a few works, some have only signed one or two cartouche pictures on the works of their teachers or have drawn a few illustrations in books by name. Quite a few are only known because they are listed in the lists of names of contemporary chroniclers as employees of the studios of Toyokuni, Kunisada and Kuniyoshi.

The prominent representatives of the school, however, were formative for the development of ukiyo-e and color woodblock prints in 19th century Japan. From around 1820 onwards, her relatives dominated almost the entire production of woodcuts: They exclusively designed actor and theater prints, as did all Genji prints. Bijin prints were mostly designed by them, only in the first half of the 19th century there was some competition in this area from Kikugawa Eizan and Keisai Eisen . Warrior images ( musha-e ) and sumō-e were initially dominated by the members of the Katsukawa school until the 1820s, from the 1830s the representatives of the Utagawa school also had a monopoly in these areas.

In the field of landscape prints and landmarks prints, the meisho-e , there were two artists, Katsushika Hokusai and Eisen, whose work was also appreciated by the public, but was overshadowed by Hiroshige's success from the early 1830s onwards. Only in the area of surimono were there notable commissions for independent artists outside of the Utagawa School or for Hokusai and his students.

Most of the members of the Utagawa School worked in Edo. From the middle of the 19th century, however, they were also dominant in Naniwa, today Ōsaka , the second center of Japanese woodblock print production. The Kunisada students Sadamasu / Kunimasu and Hirosada and the Kuniyoshi students Yoshitaki and Harusada II were the most famous representatives of the school.

Production during the Edo period

More than half of all known woodcuts were designed by representatives of the Utagawa School. Kunisada, Kuniyoshi and Hiroshige alone have delivered around 40,000 designs for all kinds of woodblock prints, not counting their book production. The woodcut production had grown to a mass market by the Tenpō period at the latest . Tens of thousands of designs for millions of prints were made. If up to then a maximum of a thousand copies of a design had been printed, the editions of some prints that were particularly popular with the public could easily exceed a few thousand. Most of the production was off the shelf, quickly drawn and easily printed. The clients, the publishers, did not ask for any special artistic aspects. It was more a question of speed in order to adapt to the rapidly changing public tastes. However, it should not be overlooked that in addition to mass-produced goods, there were also particularly beautiful designs and elaborate prints that are among the best that the Japanese art of printing of the 19th century produced.

Toyokuni I had already run a large studio in which, in particular, theatrical and actor prints were produced in series. Kuniyoshi and Kunisada's studios far surpassed that of their teacher. The masters designed the overall composition and only made a rough draft for later printing. When the studios were at their heyday, a few dozen students were busy copying the teacher's work, making the detailed drawings for patterns, decors and backgrounds, and finally making the final artwork for the artwork. Many of these students did not make it to become independent artists and were happy to receive one or the other commission to design commercial graphics. They weren't artists, they were pure craftsmen.

In just over a hundred years, the Utagawa School members have illustrated some 3,500 books. These books could consist of one or two volumes, but they could also contain more than 50 volumes. Most of the popular entertainment literature was provided with pictures by authors such as Ryūtei Tanehiko and Takizawa Bakin (Kyokutei Bakin). But there were also volumes with landscapes and textbooks that conveyed the ukiyo-e drawing style. Toyokuni I, who illustrated a good 400 books, and Kunisada I, who was responsible for the illustration of around 650 books, were particularly productive. Toyohiro, Yoshimaru (Kitao Shigemasa II.), Kuninao, Kuniyasu, Kuniyoshi, Hiroshige and Sadahide , to name only the most important , also had a notable contribution to the design of the book .

The pictures for the books were often drawn as a joint effort by several graphic artists, so that in addition to the more well-known representatives of the school, their less important students were repeatedly named in the imprint as draftsmen.

In addition to the number of 3,500 books mentioned, a few hundred shunga books and brothel guides, which are not included in the official Japanese lists, must be added. They were drawn by all of the better-known artists of the Utagawa School and, as their production was illegal, signed with a pseudonym. Throughout the 19th century, the shunga enjoyed great popularity with buyers and were a lucrative market for publishers and draftsmen alike, which from the second quarter of the 19th century was supplied almost exclusively by members of the Utagawa school.

In addition to their work as graphic artists, members of the Utagawa School also worked as painters. Less significant orders were the production of the sometimes huge theater posters that were intended to advertise certain performances of kabuki pieces. However, a few hundred if not a thousand hanging scrolls, fan pictures and wall paintings were created on private commission or even on behalf of temples, depicting actors, bijin-ga , landscape pictures , genre scenes from the theater and brothels and historical incidents in the style of ukiyo-e.

Development in the Meiji period

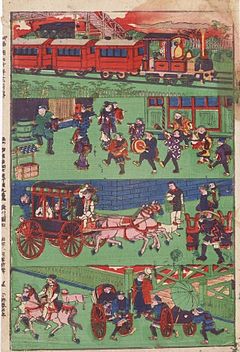

From around 1860, when trade relations with the USA and the countries of Europe were established, the focus of the production of colored woodblock prints began to shift. In the early 1860s, the so-called Yokohama-e , prints by non-Japanese, their customs and traditions , enjoyed great popularity among Japanese buyers. With the beginning of the Meiji Restoration , the kaika-e were created , which were supposed to provide information about the achievements of the new era in the sense of reporting. The prints showed Japanese in Western clothing, stone bank and hotel buildings, cobbled streets, horse-drawn carriages, steel bridges, railways, and the like. Newspapers and magazines based on Western models were created and some were illustrated with woodcuts.

The press reports on the Satsuma rebellion and, at the end of the 19th century, on the First Sino-Japanese War were also used . With the establishment of a public school system, the need for teaching and teaching material arose, which was also initially satisfied with woodcuts. Games such as Sugoroku and Uta-Garuta , handicraft sheets, dress-up figures, letterheads and advertising leaflets etc. were graphically designed, but the classic themes of ukiyo-e, the theater and its actors, the beauties of the brothels and the masters of sumo were also used , recorded in the woodblock prints, albeit to a lesser extent than in the first half of the century.

Almost all print production in the second half of the 19th century was designed by the members of the Utagawa School. The majority of the prints did not meet any artistic requirements. The drafts were drawn roughly and the printing process using the aniline inks imported from the West can only be described as ghastly. It should be emphasized, however, that color woodcuts were created throughout the Meiji period, which were artfully composed and met the highest technical requirements in their execution.

Some significant draftsmen of colored woodcuts in the second half of the 19th century are the followers of Kunisada I, Kuniyoshi and Hiroshige I, their pupils Kunisada II , Hiroshige II (Risshō I.), Sadahide and Yoshitora . The last great masters of the Utagawa school were Toyohara Kunichika , who had founded his own sub -school and who remained connected to the traditions of ukiyo-e until his death, his pupil Toyohara Chikanobu , Kawanabe Kyōsai and Tsukioka Yoshitoshi . The latter two had been trained at the Utagawa School, and their earlier work had been drawn entirely in their style. In the last decades of the 19th century, both succeeded in integrating new, western elements into their style and thus working together with other, independent artists such as B. Kobayashi Kiyochika and Ogata Gekko to become pioneers of shin-hanga .

Other, more insignificant representatives of the Utagawa school were still active in the first decades of the 20th century, such as B. Hiroshige IV., Nobukazu and Kunimine. Hasegawa Sadanobu IV died in 1999, the last active Japanese color woodcut artist, whose work echoes the ukiyo-e and the style of the Utagawa school.

Relatives

literature

- Richard Lane: Images from the Floating World. Including an Illustrated Dictionary of Ukiyo-e. Office du Livre, Friborg 1978, ISBN 0-88168-889-4 (English).

- Andreas Marks: Japanese Woodblock Prints. Artists, Publishers and Masterworks 1680-1900 . North-Clarendon, 2010, ISBN 978-4-8053-1055-7 (English).

- Amy Reigle Newland (Ed.): The Hotei Encyclopedia of Japanese Woodblock Prints . 2 volumes, Amsterdam, 2005, ISBN 90-74822-65-7 (English).

- Friedrich B. Schwan: Handbook of Japanese woodcut. Backgrounds, techniques, themes and motifs. Iudicium, Munich 2003, ISBN 978-3-89129-749-0 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Marks, p. 68

- ^ Marks, p. 96

- ^ Marks, p. 132

- ↑ see: List of members of the Utagawa school

- ↑ see: " ukiyo-e-shi sōran " (浮世 絵 師 総 覧) , "Complete bibliography of ukiyoe artists" (Japanese)

- ↑ on the dominance of the Utagawa school see Schwan, p. 246 and Lane, p. 150ff

- ↑ the database of the National Institute of Japanese Literature lists exactly 3523 titles that were created with the participation of members of the Utagawa School, Union Catalog of Early Japanese Books. (Japanese)

- ^ Marks, p. 96