Yantra tattoo

The yantra tattoo , also called sak yant ( Thai : สัก ยันต์ ), is a sacred form of tattooing that is widespread in Southeast Asia - especially Cambodia , Laos and Thailand . The practice of sak yant has been enjoying growing popularity among Chinese Buddhists in Singapore for some time . Sak can be represented with “(tattoo) sting”, yant - derived from Sanskrit yantra - with “sacral geometric figure”. The yantra has the task of concentrating (psychic) forces in a - sometimes complex - pattern or ornament and making them usable.

Tattoo process

The process of piercing yantra tattoos is known as bidhi sak (Thai: พิธี สัก - pʰítʰi sàk ). The acharn sak (Thai: อาจารย์ สัก - [ ʔatɕaːn sàk ]), literally something like "(honorable) tattoo teacher", called tattoo master, engraves the motif with a traditional tattoo instrument, called mai sak . The mai sak is a long, sharpened bamboo stick . Alternatively, a metal tip called a khem sak can be used. The tattoo artist can be a Buddhist monk , a traditional healer, or other specialist who practices magical or religious acts. Thick Chinese ink is usually used as the base material for tattoo ink. This can and is partially enriched with the bile of an enemy , with the ground skin of a monk or other ( magical ) substances in order to influence the functioning and effects of the tattoo - as by the selection of specific sayings and shapes. After the process of stinging is complete, the tattoo must be consecrated to develop its full power. This is done either by the tattoo master's blows on the still sore spot and recitation or ritual sprinkling of the tattoo (with a liquid) by several monks from different monasteries if possible. During and in preparation for the act of tattooing, incense is burned, and holy or teaching texts or mantras are recited.

history

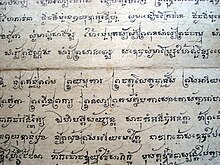

The font used for a yantra tattoo is a conglomerate of the ancient Khmer and Buddhist Pali scripts. This font is also known as Âksâr khâm ( អក្សរខម ) and was used to write palitexts on palm leaves . The style is characterized by accentuating serifs and edges. The practice of yantra tattoos seems to be traced back to the time of the Khmer kingdom of Kambuja ; at least Buddhist art forms flourished in the Khmer empire between the 11th and 14th centuries. The immigrant Thai were thus able to fall back on the substrate of Dvâravatî and Khmer art in developing their own artistic traditions .

In addition, some yantra tattoos combine elements of Buddhist art ( e.g. ritual diagrams ) with elements of the symbolic language of pre-Buddhist or shamanistic religions (e.g. animal representations) of Southeast Asia. Various symbols and representations (e.g. Hanuman ) can be traced back to the influences of Hinduism .

The mixing and fertilization of different views and artistic elements was made easier by the general openness of Buddhism to art forms and traditions. Since the 19th century at the latest, books and (teaching) writings have appeared in Thailand that deal with the creation and function of yantra tattoos and magical protective clothing.

meaning

Yantra tattoos are believed to have the function of conferring mystical powers, (magical) protection or happiness. Cambodians are of the opinion that the tattoo has a protective function, similar to a talisman . So the tattoo should keep away the evil or hardship and distress. This belief goes so far that the tattoo - according to popular belief - can even ward off physical damage, one of the properties that make body jewelry particularly popular with soldiers . Thailand is the country with the highest number of practitioners. The practice of tattooing is carried out in temples in Bangkok , Ayutthaya, and northern Thailand.

According to the traditional view - at least within the ethnic group of the Cambodian Khmer - only men can and should receive the magical tattoos. The view even goes so far that the contact with or the closer presence of women leads to some form of (magical) contamination , which among other things negatively influences or even cancels the (protective) function of magical signs and objects. This gender-specific view of the magical tattooing practice is probably strongly related to the traditional role models and tasks of the sexes within the ethnic group. For example, women were not required to wear tattoos with a protective function within their traditional area of responsibility. This view is supported by a change in tattooing practice within the Cambodian diaspora in the USA . There, more and more women are getting sacred tattoos, e.g. B. to receive magical support in your role as a business partner.

The yantra ornaments do not only appear as tattoos, but also have a protective function as mere decorations. In Thailand, clothing known as sua yantra with yantra ornaments was worn directly on the skin as a substitute for the painful tattoos. The protective effect of clothing should be in no way inferior to that of tattoos. The sua yantra can therefore be seen as a kind of interchangeable tattoo.

The motifs of the yantra tattoos are therefore not only used for their magical function as body or clothing jewelry, i.e. directly on people, but can also be used - in the form of paintings etc. - found on houses, cars and other man-made objects. Here, too, they should each exercise specific protective functions.

literature

- Ian Harris: Cambodian Buddhism: History and Practice. Honolulu 2008, ISBN 978-0-8248-3298-8 .

- Jana Igunma: Human body, spirit and disease: the science of healing in 19th century Buddhist manuscripts from Thailand. In: The Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Universities. Vol. 1 2008, pp. 120-132.

- Chean Rithy Men: The Changing Religious Beliefs and Ritual Practices among Cambodians in Diaspora. In: Journal of Refugee Studies. Vol. 15, No. 2 2002, pp. 222-233.

- Victoria Z. Rivers: Layers of Meaning: Embellished Cloth for Body and Soul. In: Jasleen Dhamija: Asian embroidery. New Delhi 2004, ISBN 81-7017-450-3 , pp. 45-66.

- Dietrich Seckel : Art of Buddhism. Becoming, wandering and changing. Baden-Baden 1980, ISBN 3-87355-204-3 .

- Donald K. Swearer: Becoming the Buddha: the ritual of image consecration in Thailand. Princeton 2004.

Web links

- Wat-Bang-Phra.de - Sak Yant temple in Thailand, with pictures and videos

- Sak-yant.com - Sak Yant Thai Khmer Buddhist Temple Tattoos (English)

- Sak Yant: Magical Tattoos (English)

proof

- ↑ http://www.buddhistchannel.tv/index.php?id=57,8938,0,0,1,0

- ↑ Archive link ( Memento of the original from July 15, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ "[...] a yantra is understood to be an instrument designed to curb the psychic forces by concentrating them on a pattern, and in such a way that this pattern becomes reproduced by the visualizing power of a person. But it is also regarded as a visual expression of a mantra [...]. "" See Jana Igunma, Human body, spirit and disease, pp. 128–129.

- ↑ a b c Archived copy ( memento of the original from October 1, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Chean Rithy Men, The Changing Religious Beliefs and Ritual Practices among Cambodians in Diaspora, p. 226.

- ↑ "Human bile collected from a [.] Enemy [...] the skin of a monk." See Ian Harris, Cambodian Buddhism, p. 61.

- ↑ "On completion, the tattoo must be consecrated. [...] is to receive ritual aspersion [...]." See Ian Harris, Cambodian Buddhism, p. 61.

- ↑ Ian Harris, Cambodian Buddhism, p. 61, also Donald K. Swearer, Becoming the Buddha, p. 69.

- ↑ "The ancient Khmer alphabet is considered sacred [...]." See Jana Igunma, Human body, spirit and disease, p. 131 and Ian Harris, Cambodian Buddhism, p. 61.

- ^ Seckel, Kunst des Buddhismus, p. 94.

- ↑ "There are also significant achievements [...] where a people who subsequently entered an old cultural area only now creates their characteristic religious forms, such as the Thai people in the 14th / 15th centuries on the shoulders of the Dvâravatî and Khmer art. " See Seckel, Kunst des Buddhismus, p. 95.

- ↑ "[...] Buddhist religious and animistic tattoo designs, [...] animals and number [s] [.], Have also been worn by the Yao and Meo of [...] Thailand and Laos." See Rivers, Layers of Meaning, p. 51.

- ^ "Wearing the Hindu-originated painted images [...]." See Rivers, Layers of Meaning, p. 51; on the use of Nagas and Garudas see Jana Igunma, Human body, spirit and disease, p. 131.

- ↑ "Buddhism knew [...] how to come to terms with the native, traditional spiritual powers, so that it was not uncommon for a kind of syncretism to develop, to which it gave its sign and stamped its stamp more or less strongly; [...] ]. " See Seckel, Kunst des Buddhismus, p. 11.

- ↑ "Manuscripts dealing with the broad field of spirituality include books on [...] as well as [...] tattooing manuals and protective shirts." See Jana Igunma, Human body, spirit and disease, p. 121.

- ↑ leisurecambodia.com

- ↑ "Traditionally, magical tattoos are only for men, and the power of tattoos itself can be decreased when a man wearing them comes into inappropriate contact with women. Customarily, women are believed to be dangerous sources of pollution, which can affect sacred and magical objects. " See Chean Rithy Men, The Changing Religious Beliefs and Ritual Practices among Cambodians in Diaspora, p. 226 and Ian Harris, Cambodian Buddhism, p. 61.

- ↑ "[...] transformation of religious conceptions regarding magical power as related to gender. [...] The changes in relation to magical tattoos are also embedded in the shifting economic status of Khmer women and the social networks which they have established in American society. [...] Thus, if a woman is to lead the family [...] she needs some kind of protection. Magical tattoos are one of the solutions. " See Chean Rithy Men, The Changing Religious Beliefs and Ritual Practices among Cambodians in Diaspora, p. 227.

- ↑ "[...] the shirts are believed to make the body invincible. [...] many have worn these shirts to make themselves bullet-proof." See Rivers, Layers of Meaning, p. 51; "[t] he ancient Khmer alphabet [...] was often used to write down the invocations (mantra) in the shirt." See Jana Igunma, Human body, spirit and disease, p. 131.

- ↑ "[...] magic talismanic shirts are viewed as kinds of removable tattoos." See Rivers, Layers of Meaning, pp. 51-52.

- ↑ "Every Cambodian house has a yantra above the entrance door to protect the house and keep bad spirits from entering." See Chean Rithy Men, The Changing Religious Beliefs and Ritual Practices among Cambodians in Diaspora, p. 230.