Tasmanians

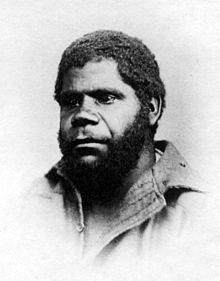

The Tasmanians are a collective term for the tribes of Aborigines who Tasmania inhabited.

The British colonization since the discovery of Tasmania at the beginning of the 19th century led to its displacement, which quickly led to genocide due to the lack of retreat areas and the small population of the Tasmanians . Almost a century after their discovery by the English, the Tasmanians were considered exterminated. The Tasmanian cultural heritage is maintained by descendants of Tasmanian women and European men to the present day.

history

Ethnogenesis

The oldest recorded human traces in Tasmania are dated to around 35,000 years before Christ. Since Tasmania and Australia were still connected at that time, the Tasmanians partly shared the culture of the Aborigines of the main Australian continent.

About 8000 years ago the last land connection between Australia and Tasmania, the 200 km wide Bass Strait, was interrupted by rising sea levels at the end of the Vistula glaciation. The Tasmanians were thus isolated, and since then a separate development has taken place. Whether the physiological differences between the Tasmanians and the Aborigines (slightly lighter, reddish skin, curly hair) as an evolutionary adaptation to life in Tasmania or as an indication of the colonization of the Australian continent in several waves (the last of which did not reach Tasmania) is to be understood is controversial.

Tasmanians before 1803

The Tasmanians were divided into the following tribes: (regions in brackets)

- Lairmairriener (Big River)

- Nuenonner (southeast)

- Tugi (southwest coast)

- Tommeginner (north)

- Tyerremotepanner (Northern Midlands)

- Plangermairiener (Ben Lomond)

- Pyemmairiener (northeast)

- Pirapper (northwest)

- Paredarermer (oyster bay)

Tasmanians after 1803

When the Europeans arrived in 1642, there were probably around 5,000 Tasmanians. In 1804 the English founded Hobart (then Hobarttown) as a penal colony, the Tasmanians living there were killed or driven out. Whalers kidnapped women and girls on their ships for sexual purposes , and diseases ( flu , measles , smallpox ) that were brought in also decimated the Tasmanians who lacked immunization.

As a result of the increasing colonization and agricultural use of their land, the Tasmanians were displaced into the most inhospitable regions of Tasmania, while the newcomers took possession of the fertile and rich landscapes. The Tasmanian culture was thus deprived of its livelihood; there was no integration whatsoever into the culture of the colonists.

The Tasmanians defended themselves in the so-called Black War of 1824–1831 using guerrilla tactics , but were unable to withstand the materially and numerically superior English because of their smaller number.

Tasmanian extermination

The information about the original number of Tasmanians varies between 3,000 and 15,000. In 1830 there were only about 300 Tasmanians left. At the end of the so-called "friendly mission" of the Black Line by George Augustus Robinson , the plan to deport the Tasmanians to the Wybalenna reserve on Flinders Island , an island off Tasmania, was implemented. Only 220 arrived there, the others had died on the transport. They had to submit to a European way of life and were Christianized, but the majority perished of depression, alcoholism and illness. In 1847 only 47 Tasmanians lived there, they were relocated to Oyster Cove near Hobart. In 1869, William Lanne, the last Tasmanian, died in 1905, Fanny Cochrane Smith , the last Tasmanian woman.

present

Today's Tasmanians are all descendants of Tasmanians and Europeans (to a large extent from Fanny Cochrane Smith, who was married to a man of European descent) and live on Tasmania and some offshore islands. They see themselves as legitimate descendants of the Tasmanians, but their status is not entirely undisputed. Since the mid-1970s, the interests of these Tasmanians have been represented by the Tasmanian Aboriginal Center , which also manages the protected areas established since 1999.

Culture

technology

The Tasmanians did not take part in some of Australia's technical innovations such as the boomerang due to their isolation after the separation of the two land masses. As neither of the cultures knew of ocean-going boats, there was no subsequent cultural exchange.

Since Tasmania is considerably smaller than the rest of Australia and also densely forested in the interior, it could only support a small population of a hunter-gatherer culture. The total population is estimated by various sources to be between 5,000 and 20,000 people.

This small population implied not only a low innovation potential, but also the gradual loss of already existing cultural achievements such as fishing, spear hunting or clothing. This cultural decline is perhaps due to the fact that the Tasmanians only lived in very small groups and a permanent and complete transmission of knowledge could not be guaranteed. The fishing and the manufacture of bone tools, which were still known at the time of the separation, disappeared in the following millennia; the loss of tool knowledge then led to the loss of clothing production. It seems unlikely that the Tasmanians actually, as evidence indicates, did not yet master the use of fire.

It is also discussed that after this cultural downturn, the Tasmanian culture found itself in a renewed, slow upswing, which calls into question the traditional assessment of the Tasmanians as an isolated and declining culture. So canoes were developed in Tasmania and a semi-sedentary village culture emerged.

language

The Tasmanian language died out with the Tasmanian culture, the last speaker being Fanny Cochrane Smith. Smith was well aware of her importance as the final spokeswoman for Tasmanian and the “guardian” of Tasmanian culture. In 1899 she picked up two wax cylinders with Tasmanian songs, which are the only native documents of the Tasmanian language and music.

Due to the short period between discovery and complete extinction, the colonists' disinterest in Tasmanian culture, and the lack of writing in Tasmanian, few examples of the language have survived. On the basis of this, Tasmanian has occasionally been shown as related to some Papua languages in New Guinea , but a definitive assignment of the language to this group is not possible.

"Non-destructive-aggressive society"

The social psychologist Erich Fromm analyzed the willingness of 30 pre-state peoples, including the Tasmanians, to use ethnographic records to analyze the anatomy of human destructiveness . He finally assigned them to the “non-destructive-aggressive societies”, whose cultures are characterized by a sense of community with pronounced individuality (status, success, rivalry), targeted child-rearing, regulated manners, privileges for men and, above all, male tendencies to aggression - but without destructive ones Tendencies (destructive rage, cruelty, greed for murder, etc.) - are marked. (see also: "War and Peace" in pre-state societies )

literature

- Julia Clark: The Aboriginal people of Tasmania. Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Hobart 1983

- Tim F. Flannery : The future eaters. An Ecological History of the Australasian Lands and People. Grove Press, New York 1994, ISBN 0-8021-3943-4

- Harald Haarmann : Lexicon of the lost languages. 2002, p. 196 f. ISBN 3-406-47596-5

- Henry Reynolds: Fate of a free people. A radical re-examination of the Tasmanian wars. Penguin, Melbourne 1995

- Lyndall Ryan: The Aboriginal Tasmanians. Allen & Unwin, London 1996, ISBN 1-86373-965-3

- Dirk Halfmann: The Tasmanian Aborigines - Source-critical inventory of previous research results. Freiburg 1998, ISBN 978-3-638-10031-1

- Jared Diamond : The third chimpanzee . Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2000, ISBN 978-3-10-013912-2 , Chapter 16, p. 348 ff.

Web links

- Markus Möslinger: The human settlement history of Tasmania. In: M. Magnes, H. Mayrhofer (Hrsg.): Flora and vegetation of Tasmania. An introduction to the excursion area of the Institute for Botany at the University of Graz in November 1996.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Adam Jones: Genocide. A Comprehensive Introduction. Routledge, London 2011, ISBN 978-0-415-48618-7 , p. 120.

- ↑ Erich Fromm: Anatomy of human destructiveness . From the American by Liselotte et al. Ernst Mickel, 86th - 100th thousand edition, Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1977, ISBN 3-499-17052-3 , pp. 191-192.