History of Tasmania

The History of Tasmania is from the end of the last ice age (about 10,000 years ago) to the present. The island was settled by Aborigines about 35,000 years ago. It was colonized by Great Britain in the 19th century. This article describes colonial history and resistance to it.

Colonial history

In order to forestall other claims, the British founded Risdon Cove, their first settlement on Tasmania in September 1803 , which was to be followed by two more in the course of a year.

First colonization

The first settlement ('Risdon Cove') was carried out from Sydney under the direction of Lieutenant John Bowen . He arrived in September 1803 and founded the first settlement on a branch of the Derwent in an area proposed by George Bass in the southeast of the island . He was accompanied by 94 prisoners and soldiers from Sydney. The following February, over two hundred prisoners and military personnel came again under the direction of Colonel David Collins . This time sent directly from England, after a tour of Port Phillip and Risdon Cove , they built the settlement Sullivan's Cove, later Hobart, on the opposite bank of the Derwent .

Second colonization

In November there was the second wave of occupations from Sydney. Governor Philip G. King divided the island into two administrative districts: South of the 42nd parallel in the district 'Buckingham' with the two already existing settlements. In the northern district of 'Cornwall' he had a third settlement founded. Under the command of Lieutenant Governor William Paterson , George Town was founded near Port Dalrymple (now Launceston ) at the mouth of the Tamar River .

None of the three settlements were initially self-sufficient . After Great Britain's claims to Tasmania were cleared, the two governments kept themselves covered with subsidies , so that the colonization of Tasmania proceeded very slowly.

Twenty years after the initial settlement, Tasmania's European population reached 10,000, and in 1923 large parts of the island were still unexplored. In addition to the first three settlement centers, a few more developed in the vicinity along the rivers - the Tamar in the north and the Derwent in the south - or the coastline. After Tasmania had been settled for thirty years, the road between the island's capital Hobart and the capital of the northern district of Launceston was inadequately developed.

Seal fishing

Chronologically overlapping, another development took place alongside colonization, the beginnings of which go back to the 1790s. This development - the establishment of seal fishing and the hunt for other marine mammals in the Bass Strait and the west coast of Tasmania - had already produced a negative attitude among the islanders towards the Europeans in pre-colonial times.

Initially, the sealers were only dropped off seasonally on the islands and picked up again at the end of the fishing season. After the demand for oil , meat, skin and hair of marine mammals increased, permanent, year-round fishing stations were increasingly established.

Women robbery

In the course of this development the seal hunters' interest in Tasmanian women increased. Initially, at the end of the season, they brought the women back to the mainland and made do with one Aborigine each. However, once the efficiency of their labor was recognized both in the seal hunt and in the daily gathering of food, the kidnappings became devastating. Increasingly, the women were abducted with the help of violence and deported to islands inaccessible to the Aborigines . At the beginning of sealers era Aboriginefrauen were by Europeans in barter acquired. As a rule, these were not women from their own local group, as is sometimes claimed, but rather women whom they themselves had stolen from neighboring groups. After the first violent kidnappings, the path to peaceful bartering was blocked. The sealers attacked the inhabitants of the north and east coasts, killed the men and abducted their wives, as revealed in the Cape Grim massacre investigated by George Augustus Robinson .

Barriers to colonization

At first the colony was not very attractive for free settlers . The fallow land of the few plains had to be made arable with great effort.

In Europe, there was also the opinion that the indigenous people were dangerous savages. The high proportion of prisoners among the European population was also viewed with suspicion. In 1804 there were more than four prisoners for every free settler, although it should be borne in mind that these 'free' settlers usually did not settle there voluntarily. Strictly speaking, it was not settlers, but soldiers, civil servants and craftsmen who were posted to Van Diemens Land.

No other Australian colony has deported so many prisoners as Tasmania. A total of 74,000 were exiled to the island, including 12,000 to 13,000 women. It was not until 1825 that the ratio between free and deported Europeans was balanced: of the approximately thirteen thousand inhabitants, only half were prisoners for the first time. In the following years the ratio improved somewhat in favor of the free settlers. But deportation of detainees intensified in the mid-1830s, and peaked in the 1840s when deportation to New South Wales ceased. The population development of the free settlers must have been similar, because in 1844 there were still 30,000 prisoners for a total of 60,000 Europeans.

Another imbalance also contributed to the colony's slow development. In the early years there were hardly any women in Tasmania - at least not European ones. In 1828 there was only one woman for every four men. In 1840 there were not even half as many women as men. The discrepancy in the gender ratio decreased only very slowly over the years, so that at the beginning of the twentieth century there was still no balance. There have been numerous requests to send single women to the colony; such a measure was blocked by the bourgeois society of the young cities, as they feared that prostitution , which was already rampant , could be exacerbated. This thoroughly controversial argument was based on the prevailing attitude at the time; a respectable woman would never go on such a journey alone.

Another obstacle was the fact that many convicts had escaped at the beginning of the colonization. Some of these joined the seal hunters of the surrounding islands or roamed the country in gangs robbing, looting and murdering. In 1805, in order to avoid an impending famine in the young colony, they were allowed to hunt for their own food. Many did not return from the woods. These gangs ('bushrangers') were perceived by the early settlers as an even greater threat than the indigenous population themselves. This problem was finally resolved in 1817 under Lieutenant Governor William Sorell .

Assaults

Despite all these adversities, the population of Europe grew slowly but steadily. As the population grew, the pressure on the Aborigines increased.

In May 1804, the Royal Marines killed around forty Tasmanian Aborigines near Risdon. From this point on, the willingness to use violence and the potential for conflict increased steadily. The military were increasingly determined, but were outdone by the civilian settlers who committed a myriad of crimes against the pre-colonial population. In this context, the civilian settlers are usually subdivided into occupational groups, as all these groups assumed different roles when the escalation began. In addition to soldiers, police officers and civil servants, who mostly acted on behalf of the government, five main groups are distinguished:

The citizens of the burgeoning cities , who mostly only knew the events from hearsay, played only a subordinate role. However, they exercised their influence in the government as representatives of public opinion.

Of the seal hunters already mentioned , who did not rob the Aborigines of land but their wives, most of the most cruel crimes were committed, which are often hard to beat in terms of perversion. They severely disrupted the gender balance and provoked feuds among the tribes, which in turn fought over women.

There were individual differences among the farmers who tilled their cheaply acquired land near the settlements, and the sources usually paint a neutral picture of the farmers. But some of them also made fun of ambushing the indigenous people ('black crows') and killing them. Its worst influence was believed to have been the land grabbing, which over the years created immigration-related population pressures among the Aborigines. In the period from 1811 to 1814 alone, the area under cultivation increased from around 3,000 to around 12,000 hectares.

The crimes that have become known and committed by prisoners against the Aborigines were only the tip of an iceberg. They even fought among themselves and made life difficult for the white settlers. However, like the seal hunters, they were not involved in the land grab.

The ranchers and shepherds , whose stations were mostly on the edge of the populated areas and thus out of reach of the law, were in no way inferior to the sealers and prisoners. What these three groups have in common is that, although their actions were largely hidden from the public, innumerable atrocities have been handed down. Between 1811 and 1814, the number of sheep in Tasmania rose from 3,500 to 38,000, so that the share of the ranchers in the land grab was enormous, especially since they often drove their animals illegally to graze in the wild.

crime

The Tasmanian Aborigines were raped and otherwise tortured, castrated, enslaved, mutilated, burned alive, poisoned or otherwise killed and then partly fed to the dogs. After only thirty years of settlement, the formerly several thousand Aboriginal population was exterminated except for a meager remnant of two hundred individuals. The government did not approve this development until 1926, but tolerated it through its indecisive action.

Only once have Europeans been held accountable for such violence: two men were publicly flogged for mistreating Aborigines. One had cut off a boy's ear, the other a man's finger to use as a pipe tamper.

It is all the more astonishing that at the beginning of the colonial era, Europeans were able to move unmolested through larger groups of Aborigines. In 1824 the Hobart Town Gazette wrote: "On the whole, the black natives of the colony are the most peaceful creatures in the world".

Apart from women robbery and murder, the indigenous population of Tasmania was decimated by rampant epidemics and the rapid decline in game populations. At first the Europeans hunted the game only to supplement the scarce food; later there was a lively trade in skins. Then there were the countless dogs that reproduced unhindered on the island. An early settler, the Reverend Knopwood, proudly noted in his journal that his dogs killed nearly seventy kangaroos in just two months.

resistance

Although the Tasmanian Aborigines had little to oppose the white settlers and prisoners, who were outnumbered and possessed better weapons, they still offered bitter resistance to their expropriation and extermination. There are traditions of an Aborigine named Walyer who fought fiercely against the intruders. She organized and directed targeted attacks on white soldiers and settlers.

Martial law

As a result, the government, which until now had only indecisively appealed to the settlers' common sense, was forced to take vehement action. On November 1, 1828, she imposed martial law on the Aborigines, who were ultimately released for legal shooting.

In February 1830, an additional bounty was offered for every Aboriginal captured alive. During this period so-called 'roving parties' were founded. Bounty hunter troops officially assigned by the government to lock the Aborigines on reservations. Two leaders of these search parties are of interest to the research as informants: Jorgen Jorgenson , a Danish adventurer, and John Batman , an immigrant from Australia. The latter is usually portrayed in the sources as being well-disposed towards the Aborigines. Both were often outside the settlement area and had numerous contacts with the indigenous population.

Restriction of human rights

In addition to the imposition of martial law, four further edicts and proclamations from this period are of historical interest:

Among these, the Proclamation of Governor Sorell is a positive exception. It is often described in the sources as the most just, far-sighted and sincere document of the colonial government. This promising appeal was not heard by the violent settlers.

On November 29, 1826, two years before Governor George Arthur issued martial law, he published the following demand: “Should it be noticed that one or more tribes are determined to attack, rob or murder the white residents, then any person may stand arm and join the military to evict them by force. The tribes in this case can be seen as open enemies ”. Since the exact circumstances of the violent riots usually eluded the public, the perpetrators had a free hand.

On April 15, 1828 Arthur decided to have the populated areas cordoned off by an armed chain of posts and only allow Aborigines whose leaders had a passport issued by him to pass. In addition, he gave "hereby the strict order to all original inhabitants to withdraw immediately and [...] on no pretext [...] to re-enter the populated areas [...]". Certainly an Aborigine never heard of this decree, because there is no evidence of measures to this effect and communication was impossible due to the language barrier.

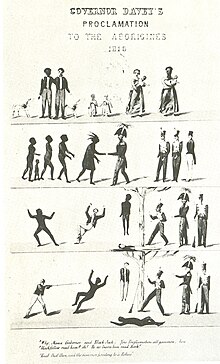

It was probably Arthur too, who grasped the full scope of the problem that the Aborigines could not possibly obey something they had no knowledge of. He had colorful posters drawn up, which were supposed to show in the form of a picture story that blacks and whites were equal before the European court. They were placed on trees in the woods. This peak of helplessness was mostly covered with malice in English literature. But even in the ethnological magazine Globus , published in Braunschweig , people were already ironic about these tables, which were held “in the style of the morality pictures at the fairs”: “The information medium was considered to be ingenious. It was decided that the content of the decrees should be made clear by illustrations to the limited understanding of the savages. These should be nailed to trees in the woods for the night of the blacks, and probably also for the benefit and piety of the cockatoo and opossum ”.

In addition to these edicts, promising attempts were made during Arthur's reign to settle the armed conflicts. On March 7, 1829, a government advertisement appeared in the Hobart Town Gazette . We were looking for "a steady person of good character, who can be well recommended, who will take an interest in affecting an intercourse with this important race, and reside on Brune [Bruni] Island taking charge of the provisions supplied for the use of the natives of that place ".

Food had been deposited in the woods for the locals for six months and three Aborigines were caught. A guardian was sought for this and subsequent prisoners, whose task it was to manage a reservation on Bruni Island. A thirty-eight-year-old bricklayer was selected from a total of nine applicants: George Augustus Robinson seemed predestined for this job due to his involvement in several charitable institutions. In order to save the Aborigines from certain doom, he made the decision to accommodate as many as possible in a reservation, far away from the settlers.

reservation

Black War

For the Europeans, the war began with the imposition of martial law in 1828. From the point of view of the pre-European population, such a temporal fixation of the so-called Black War is incomprehensible: They had no access to government decrees and there was hardly any increase in the violence inflicted on them from 1828 onwards more is possible. If you take their guerrillas as a yardstick, this date seems justified. Their attacks on Europeans increased significantly after 1828, but from 1831 their resistance waned. The first European was killed by the Aborigines in 1807. During 1808, twenty years before the war officially began, their warriors had killed twenty Europeans. A total of 176 Europeans died in combat operations in the first twenty years of settlement.

A mood of panic increased among the settlers. Arthur's government asked London for military assistance in 1830, but this was withheld. In view of the demographic development of the two counterparties, such a request is incomprehensible at this point in time. Of the formerly around five thousand Aborigines, only fewer than three hundred were still alive. Half of them were female, so that minus the old, children, prisoners and already 'pacified' less than one hundred combat-ready Aborigines faced an overwhelming power of twenty-four thousand Europeans. However, Arthur felt compelled to take steps parallel to the roving parties and Robinson's efforts to put a stop to the resistance once and for all. He organized a military operation of enormous financial and organizational proportions to capture the survivors and banish them from Tasmania. He managed to mobilize a force consisting of the military, police, prisoners and free settlers, which was at least three thousand strong.

Black Line

Their use began at the beginning of October 1830 and lasted seven weeks. Their task was to drive the Aborigines in front of them in an impenetrable chain formation. They were then to be picked up at the southern tip of the island and loaded onto the waiting ships. The government's plan failed: the result of this several thousand pound operation was shameful. When the settlers reached the southern tip of the island and prepared to surround the locals, not one Aboriginal was encountered. Only in the course of their advance was it possible to kill two Aborigines and take two others prisoner. This measure, known as the Black Line ('Black String') by Arthur, was a complete failure. Nevertheless (or precisely because of that?) It enjoys recognition in the scientific literature. The descriptions are as numerous as they are contradictory.

George Augustus Robinson had been commissioned by the British to bring the remaining Aborigines into the reservation in a peaceful way. He was in contact with all three hundred survivors during his mission. Less than four years after the 'Black Line' he had succeeded in deporting all Aborigines from Tasmania. His plan was to build a settlement on an island on Bass Strait. After several attempts, his final choice fell on Flinders Island. A total of 220 Aborigines were deported to Flinders Island, with never more than 130 living there at the same time. On the island seventy kilometers long and thirty kilometers wide, the survivors were protected from the murdering settlers, but there was no end to the death. Eighty of the three hundred Aborigines died before they even reached Flinders. Because of epidemic infectious diseases, the death rate there was also very high from the start. By December 1833, thirty-three members of the West Coast groups had died. Including the forty-two newcomers brought in by Robinson, 111 residents lived in the settlement at that time. This gender-balanced group was initially cared for by 43 Europeans.

Reservation in Wybalenna

In early 1836 Robinson took over the management of the "Wybalenna" reservation. He attempted to civilize and Christianize the 123 surviving Aborigines. They were taught reading and writing and were required to attend the services given by Rev. Robert Clark on a regular basis. Due to the persistent failures, the service was later limited to singing hymns and teaching was given up entirely. Nevertheless, Robinson and Clark, who regularly had to answer for their work before the government, tried to keep up the appearance of continuous progress. One of these dazzling works was the publication of its own newspaper, which was supposedly written by the Aborigines. However, this newspaper was written by three black youths who were probably already able to write and read before they came to the reservation.

To promote Europeanization, Robinson introduced monetary transactions. From now on the Aborigines were paid for their work. The men were employed as hunters (fur trade), gardeners, shepherds, police officers and in road construction. The women did housework and handicrafts and processed the 'mutton birds' they had caught. But even these activities gradually fizzled out after they had only begun hesitantly.

Because of the high death rate, a general despondency spread among the residents. Thirty more Aborigines died in 1834, and those left behind became increasingly resigned. Even the establishment of a small infirmary, which was looked after by a nurse, could not prevent this development. Robinson's commitment also waned over time. He was only trying to maintain his reputation as the head of 'Wybalenna'. Of the forty months he was in charge of the reservation, he was only twenty-seven months on Flinders Island.

Just a few months after starting his tenure in the reservation, he had applied for the Aboriginal protectorate in the Port Phillipp District in Southeast Australia. The negotiations dragged on, so that a positive decision on his application was not made until August 10, 1838. He took over the protectorate in Southeast Australia, but could not, as originally planned, take all the Tasmanian Aborigines with him.

At the time of Robinson's departure for Australia on February 25, 1839, a flu epidemic was raging in the reservation. Of the remaining 96 inmates, only eight were transportable. When Robinson's family later moved to Port Phillipp, they brought seven more Aborigines with them. Robinson's son, George, stayed behind to head the reservation with the rest of them, eight more died a week after Robinson's departure. Of the thirteen Tasmanian Aborigines deported to Australia, only five saw Tasmania again. Two were publicly hanged for murder in Australia and eight more were carried away by illness.

In 1847 the living Aborigines sent a petition that they want to live in their ancestral land again. The reservation in Wybalenna on Flinders Island was closed and the now 47 Aborigines were relocated to Oyster Cove on the D'Entrecasteaux Canal in southeast Tasmania. At that time, Robinson was still working as a protector in Australia. He visited the remainder only once again in April 1851 at Oyster Cove before returning to Europe forever in May 1852. Their living conditions had deteriorated compared to Flinders Island. The area was a wet meadow and the wooden buildings were exposed to the cold south wind. As a result, most of them became ill and addicted to alcohol and were abandoned to oblivion or death outside of society without any noteworthy support. On the fiftieth anniversary of Hobart's founding, sixteen Tasmanian Aborigines were still alive in Oyster Cove.

Truganini

On May 8, 1876, Truganini died , who was then the last unmixed Tasmanian woman. Truganini is the Aboriginal people about whom most of the detailed information is known. As Robinson's long-time companion in Tasmania and Australia, she can also be considered his main informant.

However, several thousand descendants of female Aborigines and European sealers live in Tasmania and on the islands of the Bass Strait today.

History in tabular form

- In 1642 the Dutch navigator Abel Tasman discovered the island for the Europeans. He sailed on behalf of the Governor General of the Dutch East Indies, Anton van Diemen , which is why he also called the island Van Diemens Land.

- In 1798, Captain Matthew Flinders circled the island and thus demonstrated Tasmania's island character, while Tasman had assumed a peninsula.

- 1803 Tasmania became British . The British made it a penal colony . The more severe cases were brought to Tasmania because the island's smaller size made it easier to monitor.

- 1825 Tasmania was declared a colony in its own right.

- 1836–1843 The famous British navigator and north polar explorer Sir John Franklin was governor of the island.

- In 1853 the island got its current name in honor of the discoverer.

- In 1856 Tasmania acquired its own constitution and government .

- In 1871 the first railway was opened on the island.

- In 1901 the Australian colony joined the Australian Confederation .

- 1906 - 1922 the coal railway " Sandfly Colliery Tramway " operates .

- In 1917 the British King George V donated the national coat of arms with two bag wolves as shield holders.

- 1936 The last bag wolf to live in a zoo dies.

- 1975 The Tasman Bridge over the Derwent River is rammed by a ship, collapsing some segments of the bridge and separating the eastern and western parts of Hobart .

literature

- Lyndall Ryan: Chronological Index: List of multiple killings of Aborigines in Tasmania: 1804-1835. Online Encyclopedia of Mass Violence. Available online (English)

- Lloyd Robson & Michael Roe: A Short History of Tasmania. 2nd edition 1997. Oxford University Press, Melbourne. ISBN 0-19-554199-5

- Tasmania . In: Meyers Konversations-Lexikon . 4th edition. Volume 15, Verlag des Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1885–1892, p. 528.

- Nicholas Shakespeare: In Tasmanien (novel) , 2005, Marebuchverlag, Hamburg, ISBN 3-936384-40-1

- Dirk Halfmann: The Tasmanian Aborigines - Source-critical inventory of previous research results, 1998, ISBN 3-638-10031-6

Individual evidence

- ↑ [1] , accessed on June 11, 2020

- ↑ cf. but Fanny Cochrane Smith , who only died in 1905.