Fernando Vázquez de Menchaca

Fernando Vázquez de Menchaca (* 1512 in Valladolid ; † 1569 ), also known by his Latin name Fernandus Vasquius, Spanish lawyer and humanist , belongs to the group of the Spanish Late Scholasticism or School of Salamanca .

Life

Fernando Vazquez de Menchaca was initially finance official in his hometown of Valladolid , where he studied from 1538 and from 1541 at the University of Salamanca , the Roman law . In 1551 he became professor for the Justinian Institutions in Salamanca. His career took him a year later as a judge to the supreme court of the kingdom in Seville and from there in 1553 back to the supreme financial authority in Valladolid. As envoy of King Philip II , he took part in the Council of Trento in 1561 together with Diego de Covarrubias y Leyva . In 1567 he was appointed secular and legal cathedral chapter in Seville .

meaning

Vázquez had a great influence not only on Spanish Catholic science, but also on Protestants. Hugo Grotius in particular often quotes him and calls him doctor Hispanicus and decus Hispaniae . Like other representatives of the Spanish late scholasticism, he fell into oblivion after Grotius. When it was rediscovered in the 19th century, his political statements, such as the freedom of the seas, initially led to the impression that Vázquez was “only” a political author (Kaltenborn). However, the enormous influence that Vázquez had on the development of modern natural and international law was soon recognized.

Vázquez is one of the few secular lawyers who draw on the rich theological literature of " Spanish Late Scholasticism ". Simultaneously with the connection between theology and jurisprudence, Vázquez emancipates natural law, which he extends to include the ius gentium primaevum , from revelation by equating the ius divinum (with the exception of the sacraments) with the ius naturale . Vázquez founds the original freedom and equality of all people, popular sovereignty, community of goods and the principle of occupation on natural law. Contract and marriage, domination, slavery and private property are the result of corrupt positive law. With the help of natural law, Vázquez criticizes positive law. So he rejects an absolute claim to worldly or spiritual power. In private law, Vázquez used the concept of dominium to advance the theory of subjective law.

Vázquez is not only part of the “Spanish Late Scholasticism”, but also legal humanism . He shares with him the desire to return to the ancient sources, taking into account not only the Justinian texts but all ancient authors. The very open form of his works, with which he frees himself from being tied to an authoritative text, testify to his humanistic ideal. The works reveal a tremendous erudition and a certain originality and independence of their author. The explanations are often extensive and lack a consistent system, but it was not at all the intention of the author to provide the secular judge with a guide and an orientation aid through the disputes of Roman canon law. The secular jurist Vázquez can also be described as a link between theology and jurisprudence, who, together with the canonist Diego de Covarrubias y Leyva and the theologians Francisco de Vitoria and Domingo de Soto, put natural law on a new basis. In spite of all this, Vázquez is firmly rooted in the scholastic tradition, which enables him to make this tradition fruitful for secular natural law.

Works

-

Controversiarum illustrium aliarumque usu frequentium ( la ). Johann Theobald Schönwetter, Frankfurt am Main 1599.

- Controversiarum illustrium aliarumque usu frequentium ( la ). Johann Theobald Schönwetter, Frankfurt am Main 1668.

-

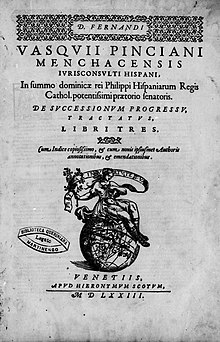

De successionum creatione, progressu et resolutione (Salamanca, 1559)

- De successionum progressu ( la ), volume 2. Girolamo Scoto, Venezia 1573.

- De successionum resolutione ( la ), Volume 3. Girolamo Scoto, Venezia 1573.

- Controversiarum usu frequentium libri tres (1563)

- Controversiarum Illustrium aliarumque usu frequentium libri tres (1564).

The former is a monograph on succession, while the latter two are compilations oriented towards natural law and focused on issues of dispute.

literature

- Camilo Barcia Trelles, Fernando Vazquez de Menchaca (1512-1569). L'École espagnole du Droit International du XVIe siècle ; in: Recueil des cours 1939 I. Tome 67 de la Collection, Paris 1939, p. 433ff.

- Francisco Carpintero Benítez, Del Derecho natural medieval al Derecho natural moderno: Fernando Vázquez de Menchaca , Universidad de Salamanca, 1977.

- Carl Baron Kaltenborn von Stachau, The forerunners of Hugo Grotius in the field of ius gentium and politics in the age of the Reformation , Leipzig 1848, p. 124ff.

- Otto Wilhelm Krause, natural rights activist of the sixteenth century. Their significance for the development of a natural private law , Frankfurt am Main 1982, p. 22ff.

- Harald Maihold, punishment for someone else's guilt? The systematization of the concept of punishment in the Spanish late scholasticism and natural law theory , Cologne a. a. 2005.

- Pedro G. de Medina y Sobrado, El aporte de Fernando Vazquez de Menchaca a la "Escuela espanola de derecho international" ; in: Informacion Juridica num. 113, Madrid 1952, pp. 909ff.

- Adolfe Miaja de la Muela, Internacionalistas espanoles de siglo XVI. Fernando Vazquez de Menchaca (1512-1569) , Valladolid 1932.

- Ernst Reibstein , The Beginnings of Newer Natural and International Law - Studies on the Controversiae Illustres by Fernandus Vasquius (1559) , Bern 1949.

- Kurt Seelmann , The teaching of Fernando Vázquez vom dominium , Cologne a. a. 1979.

- Kurt Seelmann , Vázquez de Menchaca , in: Michael Stolleis (Ed.), Juristen, Munich 1995, p. 632f.

- Enciclopedia Universal Ilustrada Europeo-Americana , Bilbao, Madrid, Barcelona 1905-30, tom. LXVII, 379.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Vázquez de Menchaca, Fernando |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Vasquius, Fernandus |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Spanish lawyer and humanist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 1512 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Valladolid |

| DATE OF DEATH | 1569 |