Stephen Hales

Stephen Hales (born September 17, 1677 in Bekesbourn / City of Canterbury in Kent , † January 4, 1761 in Teddington , Middlesex ) was an English theologian, pastor, naturalist, physiologist and inventor .

family

Hales was baptized on September 20, 1677. He was the sixth and youngest son of a total of eleven children, resulting from the marriage of Thomas Hales, the eldest son of Sir Robert Hales (ennobled under Charles II), and Mary, daughter and heiress of Richard Wood ( Esquire ), Abbotts Langley ( Hertfordshire ), emerged. A younger branch of the Hales of Woodchurch family descended from one of the most respected and oldest families of Kent, which can be traced back to the 11th century and produced a number of extraordinary personalities (around the 16th century: Crown Attorney, Vice Chancellor, barons).

At the age of 43 he married Mary Newce, the daughter of the Rector of Much Hadham, but his wife died a year later, probably in childbirth.

Stephen Hales died after a short illness at the age of 84 and was buried at the foot of the new church tower of Teddington (a memorial is also located in Westminster Abbey ) at his own request : “I want no other reward than the greatest of all rewards I have enjoy: the joy of having done something for the good of mankind. ” (Stephen Hales 1760)

education and profession

Little is known of his childhood other than that he received "good grammar lessons" at Kensington and Orpington . After the early death of the father, the grandfather, Sir Robert Hales, took over the education of the boy and enrolled him in June 1696 at Bene't (St. Benedict) College (later Corpus Christi College ) of the University of Cambridge for the study of theology with the Aiming for a priesthood of the Anglican Church . After attaining the first degree , Hales was accepted as a fellow of the college in February 1703 , in the same year he finished his studies (MA) and was ordained a deacon .

The science school at Cambridge University played an important role at that time , and was largely shaped by the physicist and mathematician Isaac Newton , who worked at Trinity College until the end of the century . Another influence that Hales brought to the scientific field came from William Stukeley , who had been admitted to the college as a student of medicine in 1703 . A small room was available to him where he could carry out a variety of experiments ( physics , chemistry , botany , anatomy, etc.). Hales not only made friends with the much younger Stukeley, but soon also began to be interested in his work. Together they listened to lectures by the astronomer Roger Cotes , witnessed the chemical experiments of John Francis Vigani (* around 1650; † 1712) in the laboratory of Trinity College and wandered around Cambridge with the botanical catalog of John Ray in their luggage.

After graduating in medicine (BM), Stukeley left Cambridge in 1709 to work as a doctor in Lincolnshire , as did Hales, who graduated from theology (BD) in August of that year, was ordained and pastor of the small parish of Teddington (Middlesex), not far away of London located on the Thames , was appointed. Here he stayed until the end of his life.

The incomes of the parish office in Teddington (then 500 inhabitants) were not very large. However, as the offspring of a respected family, Hales had enough private means to support himself. In addition, he received a benefice in Porlock (Somersetshire), which he exchanged in 1722 with the parish of Farringdon, near Winchester . Here he mostly spent the summer months. From 1719 the poet Alexander Pope lived near Teddington. Although Pope loathed animal testing and spoke out against animal cruelty, he held Hales in high regard.

power

Based on studies on the physiology of muscle movement, Hales succeeded for the first time in animal experiments to determine the arterial and venous blood pressure. Single-handedly, he was a co-founder of plant physiology, the inventor and pioneer of preventive medicine and is considered one of the founders of modern physiology .

Pastoral care and social work

In the parish work, Hales made a special effort to promote public morality (e.g. punishment for adultery ), but also made sure that the churchyard was enlarged (1734), had a new church tower built and helped the community to obtain a usable water pipe (1754).

Hales also played an important role in the enforcement of the state-controlled alcohol sales ( Gin Act 1736), since 1733 the uncontrolled consumption of alcohol in England had led to terrible social misery.

Georgia Colony

Since 1732 Hales was a member of the founding committee of the American colony of Georgia . The idea of the colony was initially based on philanthropic ideas: It was about countering pauperism with emigration and thereby improving the social conditions in England, on the other hand the opportunity arose to expand the British Empire to overseas territories. This private committee administered the American province from England until 1759 before it passed into the possession of the British Crown. Overall, however, power politics and commercial interests ( slave trade, etc.) were in the foreground. The botanist John Ellis named a tree from Flora Georgia in memory of Hales Halesia .

The work in the committee also brought Hales into contact with problems of seafaring : he described measures for long sea voyages (1739), constructed a ventilation system for ships that was later also used for hospitals and prisons (1743, 1758) and proposed a method of distillation of salt water before (1756). His ventilation system was also a practical application that emerged from basic research on plant breathing and rebreathing self-experiments.

Science and Research

Hales and Stukeley performed dissections on various animals, made anatomical preparations (e.g. wax cast of the bronchial system ), repeated chemical experiments (according to corpuscular, non-humoral principles) by Robert Boyle and constructed a model of the solar system according to Newton's specifications ( Orrery ). It was probably at this time (1706) that Hales carried out his first experiments to measure blood pressure on dogs . At university he had acquired basic physical knowledge, but it was only his friendship and work with Stukeley that aroused his interest in biology .

Hales was initially busy taking care of his community, but soon resumed his animal studies ( horses , dogs, sheep , deer ) to determine blood pressure (1712–1714). In March 1718, Hales (at the urging of Stukeley) informed Newton, as President of the Royal Society, of his new experiments on "the rising of sap in trees by the warmth of sunlight" . In the same year Hales was inducted into the Royal Society (FRS). The plant physiology was now his main area of research. The results of this work appeared in 1727 under the title Vegetable Staticks .

Many of his plant physiology experiments were of fundamental importance: he dealt with quantitative studies on evaporation , determined the root pressure of the rising sap, contradicted the circulatory hypothesis of plant sap, discovered the ability of plants to absorb and store gaseous substances and just missed the knowledge of their ability to assimilate . He worked in numerous experiments with gases which were bound in the various substances, and he by heating unleashed (by Joseph Black as fixed air fixed air referred), making him the investigation of respiratory - and combustion processes was leading in the animal organism. In 1733 a summary of his animal physiological studies ( Haemastatics ) was published, including the first invasive blood pressure measurement that Hales carried out on a horse.

Hales not only repeated John Hunter's experiments on bone growth (symphyseal growth), but also studied plant growth. He observed spinal reflexes in the frog (long before Robert Whytt, 1757) and probably discovered carbon dioxide by chance in the course of his ventilation and respiration studies . At the end of his life, Hales returned to animal physiological experiments ( gill breathing ).

First direct blood pressure measurement

“In December I had a live mare laid on its back and tied up. She was 14 hands tall, about 14 years old, had a fistula on her side, and was neither particularly skinny nor overly full-blooded. After exposing and opening the left crural artery about 3 inches [75 mm] from the abdomen, I inserted a metal tube into it that was about 1/6 inch. [4.17 mm] in diameter to which I attached a glass tube about the same diameter but nine feet [270 cm] long with the help of a precisely fitting second metal pipe. As soon as I loosened the ligature in the artery, the blood in the glass tube rose 8 feet 3 inches. ” (Stephen Hales 1733)

Around 1709 Hales began experiments on circulatory physiology and blood pressure in animals. One must imagine that he carried out these years of experimentation in addition to his work as parish priest of Teddington alone in his churchyard. The written summary of his results appeared much later (1733).

The first attempt at direct arterial blood pressure measurement was carried out on a horse. Hales let the blood rise from the crural artery into a three meter high glass tube and determined the height of the blood column. Then he let the horse bleed a little, caught the blood and repeated the blood pressure measurement. He repeated this experiment 25 times (with steadily decreasing blood pressure) until the horse was bled. In the second experiment, he performed a similar arterial blood pressure measurement on a gelding . In the third experiment (horse) he first determined the venous pressure in the left jugular vein, then the arterial pressure in the left carotid , the volume of the left ventricle by injecting liquid wax , the ejection rate of the left ventricle, the speed of the blood in the aorta , the amount of arterial dilatation with each heartbeat, the amount of cardiac blood and the diameter of the aorta. In this way he realized that the blood pressure in the great vessels was dependent on two parameters: the cardiac output and the peripheral resistance . On this occasion he also suspected that the increased diastolic filling of the heart is answered with an increased systolic blood output (see Frank-Starling mechanism ).

The following of a total of 25 experiments on the comparative physiology of the circulatory system (horse, ox , sheep, dogs of different sizes) dealt (mostly after the obligatory measurement of venous and arterial blood pressure) with the cardiac output, the blood speed in different sections of the arterial system Blood pressure and speed in the pulmonary artery , the influence of various fluids (e.g. brandy ) and temperatures on the vascular status, with animal respiration and digestion and others.

In order to be able to assess the difficult question of the cardiac ejection volume per minute and resting conditions, he counted the pulse rate of the animal before the start of the experiment, determined the venous and arterial pressure invasively , let the animal bleed out and then injected (with a comparable pressure via a third cannula) melted wax through the pulmonary vein into the left ventricle, which then appeared in the glass tube on the carotid . After the wax was hard, he cut out the cast of the left ventricle and determined its volume and surface : “So that a piece of wax formed in this way is entirely appropriate to the amount of blood that this ventricle receives during each diastole, and that then during the subsequent systoles is driven into the aorta. " (Hales 1733)

Awards and merits

In 1733 Hales was promoted to Dr. theol. ( University of Oxford ).

In 1739 he was awarded the Copley Medal of the Royal Society , not for his pioneering physiological studies, but for rather insignificant experiments in the dissolution of kidney and bladder stones . In 1753 he was appointed a foreign member of the Académie des sciences .

Hales was a co-founder of today's Society of Arts (Vice President 1755) and a good friend of the Prince of Wales Friedrich Ludwig von Hannover .

Hales Peak , a mountain on the Brabant Island in Antarctica , is named after him .

Fonts (selection)

- Stephen Hales: Vegetable Staticks: Or: an Account of some Statical Experiments on the Sap in Vegetables: Being an Essay towards a Natural History of Vegetation. Also, a Specimen to Analyze the Air, By a great Variety of Chymico - Statical Experiments . tape 1 . W. and J. Iurics, London 1727, OCLC 46819652 ( digitized ).

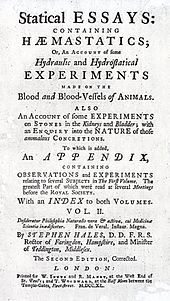

- Statical Essays: Containing Haemastatics; Or, An Account of some Hydraulic and Hydrostatical Experiments Made on the Blood and Blood-Vessels of Animals . London 1733, OCLC 685182629

- Statical Essays: Containing Vegetable Staticks; Or, An Account of some Statical Experiments on the Sap in Vegetables . London 1738

- A Description of Fans . London 1743

- An Account of a Useful Discovery to Distill double the usual quantity of Sea-water, by Blowing Showers of Air up through the Distilling Liquor ... and an Account of the Benefit of Ventilators . London 1756

literature

- GE Burget: Stephen Hales (1677-1761). In: Ann Med Hist. 7, 1925, p. 109.

- Archibald E. Clark-Kennedy: Stephen Hales. Physiologist and Botanist. In: Nature. Volume 120, 1927, p. 228.

- Archibald E. Clark-Kennedy: Stephen Hales: an eighteenth century biography. Cambridge 1929 (reprinted 1965).

- Archibald E. Clark-Kennedy: Stephen Hales, DD, FRS. In: Br Med J. 2, 1977, p. 1656.

- P. Dawson: Stephen Hales. In: Johns Hopkins Hosp (Bull.). Volume 15, 1904, pp. 185 and 232.

- WD Hall: Stephen Hales: Theologian, Botanist, Physiologist, Discoverer of Hemodynamics. In: Clin Cardiol 10, 1987, pp. 487-489.

- Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Volume 6, p. 35.

- Ralph H. Major: The history of taking the blood pressure. In: Ann Med Hist. 2, 1930, p. 47.

- John B. West : Stephen Hales: neglected respiratory physiologist. In: J Appl Physiol . Volume 57, 1984, pp. 635-639.

Web links

- Exchange of letters from Stephen Hales to Carl von Linné

- Portraits in the National Portrait Gallery

Individual evidence

- ↑ Barbara I. Tshisuaka: Hales, Stephen. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 527 f.

- ^ List of members since 1666: Letter H. Académie des sciences, accessed on November 22, 2019 (French).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hales, Stephen |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English physiologist and physicist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | September 7, 1677 or September 17, 1677 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | at Beckesbourn , Kent |

| DATE OF DEATH | January 4, 1761 |

| Place of death | Teddington , Middlesex |