John Hunter (medic)

John Hunter (born February 13 or 14, 1728 in Long Calderwood near East Kilbride in Lanarkshire , Scotland , † October 16, 1793 in London ) was a British surgeon , military doctor, dentist , anatomist and surgeon who was the founder of experimental scientific surgery applies.

Coming from a humble background and growing up in the country, Hunter started out as an assistant to his brother William in 1748 . Under the influence of his teacher, William Cheselden , Hunter developed a critical attitude towards traditional medical practice and became convinced that new insights should always be corroborated by systematic observation and experimentation. Following his teacher Percivall Pott , Hunter also tried to avoid surgical interventions whenever possible, relying instead on the body's self-healing powers .

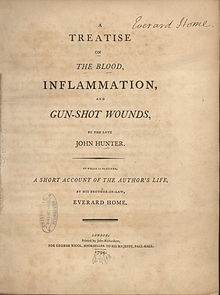

From 1760 to 1763 Hunter served as a military doctor in France and Portugal. The medical findings that arose during this time later served as the basis for his writing A Treatise on the Blood, Inflammation and Gun-shot Wounds . After returning to England, Hunter initially worked as a dentist and tried his hand at transplanting teeth. During this time he wrote a two-part work on dentistry, the first of its kind to deal with the subject in a scientific manner ( The Natural History of the Human Teeth , 1771, and A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of the Teeth , 1778).

In 1768 Hunter got a job as a surgeon at St. George's Hospital in London , which he held until the end of his life. Both in St. George's and in private lectures, he taught around 1,000 students who after his death ensured the continuation of his ideas and some of whom - such as the inventor of the modern smallpox vaccination Edward Jenner - made significant contributions to science.

In his third work, Treatise on the Veneral Disease , published in 1786 , Hunter put forward the theory , which was not disproved until 1838, that gonorrhea and syphilis are one and the same sexually transmitted disease. Hunter believed he had proven his theory in a self-experiment in which he injected the pathogen through a cut in his penis. However, the patient from whom he took the pus for the injection suffered from both diseases.

As one of the best taxidermists of his time, Hunter built up a collection of more than 13,600 objects of human and animal preparations over the years. This collection is open to the public today under the title Hunterian Collection at the Royal College of Surgeons of England , London. Large parts of Hunter's extensive handwritten estate were used by his brother-in-law Everard Home for his own purposes and then burned.

life and work

Origin and school attendance

John Hunter was born on the night of February 13-14, 1728, the tenth child of the farmer John Hunter senior and his wife Agnes, née Paul, in Long Calderwood, south of Glasgow . Like his older siblings, John attended the small village school in Long Calderwood, but from an early age showed an aversion to anything printed. According to his sister Dorothy, "he was by no means a stupid boy," but did not enjoy teaching reading, writing or any other form of learning. This meant that his knowledge of the English language remained rudimentary even for the conditions of the 18th century and later biographers such as Jessé Foot accused him of "having not been able to bring together six lines of grammatically correct English". In later years Hunter had a sizable private collection of books, but he still enjoyed the notion that he "rejects books entirely" and prefers to "study the book of the carnal body."

Early years in London

First years as his brother's assistant

In the fall of 1748 Hunter accepted an assistantship to his brother William in London . He founded the first anatomy school in England in October 1746 , building on the experience he had gained during his medical studies in Leiden and Paris .

Williams School of Anatomy heralded a new era in medical education in England. For the first time, prospective doctors were able to acquire their anatomical knowledge not only in theory, but also from their own experience and practice. In addition to lectures, the lessons consisted of anatomical exercises, for which William assured each student their own corpse as an object of study.

This promise has become one of the main challenges facing the school. The more popular Williams courses became, the greater the need for corpses. Since the bodies were hardly suitable as study objects for more than a week due to the progressive decomposition, even in winter, fresh corpses had to be brought in every day. From 1748 this work fell to his brother John as Williams' new assistant. Over the years, John developed close relationships with undertakers and professional grave robbers to meet the growing need for study objects. Entries in his case collections also suggest that he himself took part in the nightly activities of the grave robbers.

While spending his nights in cemeteries, Hunter helped his brother make specimens and look after the students during the day. He turned out to be so talented that William gave him the job of taxidermist after just six months.

Pupil of William Cheselden and Percivall Pott

Hunter spent the summer months of 1749 and 1750 as a pupil of William Cheseldens at the Royal Hospital Chelsea . Cheselden was one of the most respected surgeons of his time. His book The Anatomy of the Human Body (dt. The anatomy of the human body ) was a standard reference for medical students. However, he gained greater fame through the lateral bladder stone incision ( lithotomy ) that he introduced . For Hunter, the apprenticeship with William Cheselden turned out to be a stroke of luck. For the first time, he had the opportunity to expand his anatomy knowledge through studies on living bodies. At Cheselden's side, Hunter attended various operations and adopted his attitude that he would only operate when there was a clear prospect of success of the operation. However, Wendy Moore, one of Hunters' biographers, rates Cheselden's most important influence on Hunter as the fact that Cheselden critically questioned traditional ways in medical practice and - whenever possible - tried to underpin new insights through systematic observations and experiments. Hunter would later follow him on this path by transferring insights from the dissecting room into medical practice.

After Cheselden's death in 1751, Hunter continued his medical training under Percivall Pott . Pott was working at St Bartholomew's Hospital in London and at that time was already one of the most respected surgeons in England. Even if Pott - according to Hunter's biographer John Kobler - lacked ingenuity from Cheselden, he still had a formative influence on Hunter. In particular, he took the position of using the body's self-healing powers as much as possible. According to Kobler, Pott laid the foundation for Hunter's own medical conception.

Taxidermist and contribution to The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus

Carefully crafted specimens played a crucial role in 18th century medical education. They helped budding medical professionals identify morphological features that were otherwise difficult to see. Hunter had shown himself to be extremely adept at handling the dissecting knife early on. Initially guided by his brother William, he soon surpassed him in terms of skill. William claimed all of the specimens produced in his school as his property and claimed all of the scientific discoveries made under his roof. While John initially endured this situation in silence, his resistance to this practice rose as he became more self-confident.

In the winter of 1750, William received the body of a woman for dissection who was nine months pregnant. This gave William and John the rare opportunity to dissect a woman in the latter stages of pregnancy. The timing was also good, because decomposition started much later in winter than in the warm summer months. With the young Dutchman Jan van Riemsdyk , William gained a talented draftsman whose job it was to capture every step of the anatomical examination in pictures. Since John was primarily responsible for the dissection, William did not contribute too much to the collaborative work.

John did the delicate job of gradually opening the pregnant woman's body without damaging the unborn child. Meanwhile, the draftsman van Riemsdyk documented the individual steps with great attention to detail. While children in the womb were shown as small adults in earlier pictures, this is the first time that true-to-life representations of an unborn child in the uterus have been created . In the years to 1754 such studies could be repeated in other bodies of pregnant women, and so was under John Hunter's significant participation in the work The Anatomy of the Human Gravid Uterus Exhibited in Figures (dt. The anatomy of the pregnant human uterus, shown in pictures ), which depicts the growth of the unborn child in the womb. When William finally published the work in 1774, he reluctantly stated in his foreword that his brother John had "assisted" him in his work.

Working at St. George's Hospital and growing interest in animal physiology

In the summer of 1754 Hunter was accepted as a student at St. George's Hospital . The hospital, founded in 1733, had been expanded ten years earlier and offered space for more than 250 patients. Hunter began treating his first patients here without a medical degree. In May 1756 he was given the vacant position of House Surgeon at St. George's Hospital. After only five months, however, he gave up this post and instead continued his work at his brother William's school. Hunter's biographer Kobler suspects that William urged him to return because the lessons of his now more than a hundred students had grown over his head.

In the time after his return to Williams' school, John Hunter's growing interest in studying animal anatomy also fell. Whenever human anatomy proved to be too complex to answer questions about how individual parts of the body work, he resorted to animals, whose simpler structures often provided clearer answers. Initially, Hunter dissected dogs, horses, donkeys, and other animals that could easily be obtained at markets and from animal dealers. But soon he also turned to more exotic animal species, which he found at traveling showmen and circuses. Eventually his passion grew so much that he persuaded the guardian of the royal menagerie in the Tower of London to give him deceased exotic animals.

Work on testicular descent and the lymphatic system

There were two main areas in which Hunter excelled scientifically between 1756 and 1760: in his work on the prenatal development of the human testicle and on the lymphatic system . First, he turned to testicular descent in humans. In a paper published in 1755, Albrecht von Haller argued that this descent took place during the birth process. However, through his frequently practiced autopsies of male fetuses , Hunter knew that Haller was wrong and that testicular descent was usually completed by the eighth month of pregnancy. He provided evidence with a series of preparations in which he presented the progressive development of the process and which were received with great interest by the professional world.

During his work on the lymphatic system, Hunter made a spectacular attempt in the winter of 1758. At a time when the lymphatic system was still largely a mystery to research, one of the questions raised was whether, in addition to the lymphatic vessels , the veins were also able to absorb fats. In one experiment, Hunter cut open the belly of a living dog, opened its intestines, and poured milk into the opening. His astonished audience could observe that the lymph capillaries turned white while the veins remained filled with blood. Although the theory that the lymphatic vessels alone were responsible for the uptake of fats and fluids had been proposed a century earlier by the British anatomist Francis Glisson , it was not until 1758 that Hunter succeeded in experimentally confirming this assumption.

Military doctor in France and Portugal

New career opportunities through army service

In the fall of 1760, John decided to quit working for his brother William and instead join the British Army as a military doctor. Hunter's limited experience as a surgeon and lack of formal qualifications made it nearly impossible for him to find permanent employment in a hospital or to open his own practice. By contrast, career opportunities for doctors in the British Army had increased with the outbreak of the Seven Years' War in 1756. In addition, there was a regulation that military doctors were automatically given the right to practice in the civilian sector after the end of their service.

On Belle-Île - Findings on the treatment of gunshot wounds

His first assignment took Hunter to Belle-Île , an island off the Breton city of Lorient, in April 1761 . Here, the combined fleet and infantry units under Admiral Augustus Keppel and General Studholme Hodgson carried out two landing operations before the siege of Le Palais finally ended on June 8, 1761 with the surrender of the French and the surrender of the island to the British.

For Hunter, serving in the army was a completely new experience. The British met fierce resistance, particularly when they first attempted to land, and Hunter and his colleagues were faced with a large number of seriously injured people. Gunshot wounds and bayonet stabs had to be treated and limbs amputated. Nothing in his work at London hospitals prepared Hunter for this situation.

A more casual observation confirmed Hunter's belief in the body's self-healing powers. Five French people injured by gunshot wounds fled to a hiding place on the day of the British landing and stayed there for several days without medical care. When they were finally found, Hunter found that the French's wounds had healed better than those of their British opponents. The usual practice of military doctors for treating gunshot wounds at that time consisted of artificially widening the entry channel of the projectile, removing the bullet with tweezers - often with fingers smeared with blood and dirt -, cleaning the wound and then bandaging it. This procedure was painful, often resulted in significant blood loss, and often resulted in wound infections that could result in death. Hunter found this practice harmful. He believed that if the doctor allowed the wound to heal itself if possible, the chances of healing increased - to the point of leaving the bullet in the body in some cases. He recorded his findings in the publication A Treatise on the Blood, Inflammation and Gun-shot Wounds , published 30 years later . Based on his notes from the war, he remarked: “It is against all rules of surgery to widen [...] wounds [...]. No wound, no matter how small, should be enlarged, except in preparation for something else [ie an operation]. "

In Portugal - experiment on the hearing of fish

In July 1762 Hunter was posted from Belle-Île to Portugal, where the British fought alongside the Portuguese against the Spanish. With the fighting subsided during the final year of the war, Hunter was able to use part of his time for scientific studies. He had already dissected fish in London and discovered their hearing organ. Since its existence was doubted by the majority of anatomists of his time, Hunter carried out an experiment in Lisbon in which an assistant fired a pistol at a fish pond. Hunter observed that the fish fled to the bottom of the pond when the shot sounded and only returned to the surface after a while. But Hunter did not report his experiment to the Royal Society until 20 years later. At this point in time, the Dutch physician Peter Camper had already published the discovery based on his own studies.

Second stage of life in London

dentist

In the spring of 1763 Hunter returned to England. He was having a hard time finding a paid job again. His brother William had meanwhile hired another assistant and the large number of established surgeons in London made it seem hopeless to set up his own practice. In addition, since the Second Jacobite Rising , large parts of English society were hostile to Scots. In this situation, Hunter had no choice but to turn to the job of the lowest esteem among medical professionals and commonly practiced by quacks and barbers : that of a "dentist".

For five years, Hunter joined the well-known dentist James Spence . In this time the writing falls of his published in two parts in 1771 and 1778 work The Natural History of the Human Teeth (dt. The natural history of human teeth ) and A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of the Teeth (dt. A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of teeth ). With its detailed descriptions of the anatomy, physiology and pathology of teeth, Hunter's work was the first to deal scientifically with the subject, and at the same time the most extensive treatise on dentistry of the time.

Hunter called for the pulp to be removed before filling therapy for carious teeth and also dealt with the treatment of positional abnormalities of the teeth.

Hunter followed the idea of tooth transplantation with particular interest. Based on his belief in the regenerative power of the human body, he believed that a freshly extracted tooth only had to be inserted into another patient quickly enough to successfully grow. With printed advertisements he attracted whole groups of poorer 'tooth donors' who had their healthy teeth pulled for a few pence so that they could be used immediately afterwards by wealthier contemporaries. Hunter's scientific reputation meant that his 'tooth transplants' were copied not only in Europe but also in America. It was not until the end of the 18th century that this method, which was associated with a high risk of infection for patients, was finally abandoned.

Admission to the Royal Society , return to St. George's Hospital and marriage

In 1765 the Irish botanist and zoologist asked John Ellis Hunter a physiological study of a Siren lacertina from the family of sirenidae . Ellis had already described the animal's external characteristics and was now asking Hunter for a description of the internal structure. Hunter discovered that the adult specimen of this great arm newt had a lung in addition to its three pairs of external gills . From this, Hunter concluded that the animal, equipped with a pair of legs, was a missing link between fish and amphibians . Together, Ellis and Hunter sent their reports to the London Royal Society , where they were read on June 5, 1766. Eight months later, on February 5, 1767, Hunter was accepted as a Fellow of the Royal Society. That was three months ahead of his brother William.

After successfully completing an oral examination, Hunter was accepted into the Company of Surgeons , the association of surgeons in England (today: Royal College of Surgeons of England ), in July 1768 . In December of the same year, Hunter was officially appointed as a surgeon at St. George's Hospital in London - 15 years after he first practiced as a doctor.

His improved social position enabled Hunter to start a family. In July 1771 he married Anne Home , the daughter of a surgeon whom Hunter had met during his military service on Belle-Île. Anne and John were an unlikely couple: while Anne Home wrote romantic poems (first published in 1765), the unread Hunter was known to be difficult to express himself verbally. Anne's dealings with educated London society in literary salons were a strange world to Hunter. Alluding to Anne's poem To a Nightingale, Hunter's biographer Kobler jokes that John's interest in nightingales was limited to the composition of their innards. Outwardly, too, the two seemed to be a bad match: While Anne is described as slim and tall, 14-year-old John was more of a stocky build. Despite these differences, the partnership was apparently characterized by mutual respect. Hunter became a welcome guest in his wife's family and later adopted Anne's younger brother Everard Home as his student. The marriage had four children, two of whom died early.

Research on gonorrhea

As a medic at St. George's Hospital, Hunter treated numerous patients with sexually transmitted diseases such as gonorrhea and syphilis . Loose sex morals and the large number of prostitutes had made sexually transmitted diseases a mass phenomenon in London. At the same time, in the second half of the 18th century, the exact causes and effective treatment of these diseases still puzzled medical professionals.

Hunter wondered whether gonorrhea and syphilis were possibly the same disease. Like most doctors of the time, he believed that syphilis was just a more severe form of gonorrhea that affected not just the genital area but the entire body. But a final clarification of this question was still pending, and so Hunter devised an experiment in which a test person was infected with gonorrhea and then observed over a longer period of time. If, as Hunter suggested, the onset of gonorrhea was followed by symptoms of syphilis, then evidence would be established that both were the same disease.

As to the exact conduct of the experiment, there has long been disagreement in Hunter research. While younger biographers such as Gloyne (1950), Gray (1952), Kobler (1960) and also Moore (2005) assume that Hunter infected himself with gonorrhea and syphilis through a cut in his penis and then finally in 1793 from the long-term effects of Experiment died, Qvist (1981) denies this thesis. Qvist objects that, with the exception of Ottley (1835), all Hunters biographers until the publication of an essay by d'Arcy Power in 1925 (John Hunter: A Martyr to Science) - i.e. Foot (1794), Adams (1817), Butler ( 1881), Paget (1897) and Peachey (1924) - not to mention a self-experiment with a single word. Qvist also said that Everard Home 's autopsy after Hunter's death did not reveal any evidence of syphilis. Proof that it was actually a self-experiment is provided by Caroline Grigson, the biographer of Hunter's wife Anne. She refers to a handwritten note from Hunter, in which the latter wrote, "But since I gave myself a chancre from gonorrhea, this point has now been proven."

Hunter made a critical mistake in his experiment. The gonorrhea patient, whose pus Hunter injected himself, also suffered from syphilis, like many other patients of the time. And so the false results of Hunter's experiment were to determine research on gonorrhea and syphilis into the next century: Hunter first observed the outbreak of gonorrhea, followed by symptoms of syphilis and was convinced that he had provided the desired evidence. In 1786 he published his results under the title A Treatise on the Veneral Disease . It was not until 1838 that Philippe Ricord was able to prove that there are two different diseases.

Teaching

As Hunter's popularity grew, so did the number of his students. Of the 120 budding surgeons who began their training at St. George's Hospital between 1768 and 1772, more than half enrolled as students of Hunter. In 1771 alone, more than two-thirds of St. George's anatomy students studied with him. In addition, Hunter gave private lectures three evenings a week from October to April between 1772 and 1777. Although he these lectures under the title The Principles and Practice of Surgery (dt. The principles and practice of surgery ) competed in newspaper ads, he urged his students to avoid surgery as much as possible. Instead of covering subjects of practical surgery, he gave his audience extensive introductions to the physiology of the human body. In this way, his students should learn how a healthy body functions and what processes take place in a sick body.

Before each lecture began, Hunter took laudanum to ease his stage fright. However, speaking in front of a larger group of listeners was still difficult for him and so he read his lecture haltingly and without looking into the audience from a prepared manuscript.

His most famous students included Edward Jenner , who developed the modern vaccination against smallpox , John Morgan , co-founder of the first medical school in Colonial America, John Abernethy , English anatomist and surgeon, Anthony Carlisle , who jointly developed electrolysis with William Nicholson in 1800 discovered, as well as Astley Paston Cooper , after whom the Cooper scissors are named. Overall, the number of Hunters students is estimated at around 1,000.

Research on aneurysms of the popliteal artery

Hunters important work in the field of new surgical techniques his experiments are used to treat arterial sacs ( aneurysms ) of the popliteal artery ( popliteal artery ) . In the 18th century, aneurysms were a common phenomenon: probably caused by the wearing of tall riding boots , an aneurysm of the popliteal artery formed in the hollow of the knee , which caused severe pain when walking. This aneurysm , which occurs particularly frequently in coachmen , was usually treated by amputation . An alternative method in which the blood vessel was tied together above and below the sac and then the aneurysm was removed had proven to be risky.

Hunter approached the problem experimentally. He assumed that tying the artery above the aneurysm would be sufficient and that the blood supply to the lower leg would be ensured by diverting the blood to smaller arteries. To confirm his assumption, Hunter carried out a series of animal experiments in which he interrupted the flow of blood in the leg by tying the femoral arteries ( arteria femoralis ) together . After a few weeks, Hunter had the animals killed and, during the subsequent dissection, injected a colored liquid, known as an injection preparation , into the artery. He found out that in the meantime the blood had found other routes through smaller arteries ( collaterals ) and the blood supply to the lower leg was still ensured.

From 1785 Hunter successfully applied his surgical technique to humans and soon the technique became the standard in the treatment of aneurysms of the popliteal artery. The method spread throughout Europe under the name ' Hunter's operation '; the adductor canal ( Canalis adductorius ) used by Hunter during his operation is still known today as ' Hunter's canal '. In this context, his biographer Qvist points out that Hunter was not the first to treat aneurysms by occluding the femoral artery. Rather, according to Qvist, Hunter deserves the credit of having based the treatment method on scientific principles for the first time and having demonstrated its success in experiments.

Naturalist and collector

During his time as assistant to his brother William, John had taken an increasing interest in the physiology of animals. This interest went so far that in 1765 he bought a piece of land in Earls Court just outside London and spent much of his free time there. He had a country house built with a few outbuildings and over the years bought a large number of mostly exotic animals which he had brought to his country house. Sheep, horses, and zebras grazed in the pastures at Earls Court, and Hunter kept monkeys, jackals, lions, and leopards in the stables next to his country house. In this way he could not only study the behavior of the animals, but also dissect them after their death and gain information about their physique. Unlike other naturalists of his time, however, he was not interested in a correct classification of animals, but rather in discovering the general laws of life. Hunter sees his biographer Moore as one of the pioneers of biology , which was only established as a science in the 19th century. László A. Magyar proposed in 1994 that John Hunter could have served as a model for Doctor Doolittle in Hugh Lofting's children 's book Doctor Dolittle and His Animals .

Whenever he noticed anything unusual about a section, Hunter made preparations that he collected in his home in London . In this way, a considerable collection has come together over the years, from whale bones, the fur of a giraffe and a stuffed kangaroo to numerous animal and human specimens, to anomalies such as the brains of a two-headed calf or the body of an unborn child open back was enough. In the course of his dissections in 1775, John Hunter first applied the method of "arterial conservation" previously described by his brother William, which later became generally accepted for the conservation of corpses . A preserving fluid is injected into the bloodstream , mostly through the carotid artery . Even the remains of Charles Byrne , known as the Irish Giant , ended up in the hands of Hunter in 1783 - for a sum of £ 500, which was considerable by the standards of the time . Research assumes that Hunter combined more than 13,600 individual specimens of around 500 different species in his collection by the time he died.

In 1788 Hunter opened a museum in a complex of buildings in Leicester Square, London, which he shared with his wife Anne. Here he exhibited his precious collection. It had cost him a fortune over 30 years - Hunter himself gave the value in his will as 90,000 guineas , according to today's value around 12,000,000 pounds sterling. In addition to his animal and human preparations, fossils were also exhibited in his museum . Next to each fossil was a sample of the rock from which it was taken. Almost two decades before William Smith , the founder of British geology, Hunter realized that the same fossils are always deposited in the same rock layer.

Last years and death

In his final years, Hunter has received numerous awards for his work. As early as January 1776, the English King George III. appointed him his associate surgeon. In 1781 Hunter was accepted into the Royal Science and Literature Society in Gothenburg and in 1783 into the French Académie Royale . In January 1786 he was appointed Deputy Surgeon General of the British Army in recognition of his work as a military doctor and in March 1790 he was appointed Surgeon General .

Until his death, Hunter treated patients, continued to work in the dissection room, and taught students in his custom-made anatomical theater in Leicester Square. His most famous patients at the time included British Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger , Scottish economist Adam Smith, and Scottish poet George Gordon Byron , whom Hunter vaccinated against smallpox shortly after he was born. The composer Joseph Haydn , a close friend of Hunter's wife Anne, avoided treatment for his nasal polyps for fear of the operation, but later stated that he regretted it.

On October 16, 1793, Hunter died while sitting in St. George's Hospital. A the next day by his brother Everard Home made autopsy revealed that he had at one by hardening of the arteries caused coronary heart disease had died. Hunter was first buried in St. Martin-in-the-Fields ; on March 28, 1859, the coffin with his remains was transferred from the original burial place to Westminster Abbey .

legacy

In his will, drawn up three months before his death, Hunter had determined that most of his possessions should be sold and that his collection should be offered for purchase to the British state. In this way his debts, which had grown over the years, were to be paid off. But after his estate was auctioned off by Christie's auction house in London , it turned out that there was no more money left for his wife Anne . In addition, the British state, in the middle of the war with France, was not interested in acquiring Hunters Museum. Prime Minister William Pitt is reported to have exclaimed angrily on that occasion, “How! Buy preparations! Why, I don't have enough money to buy gunpowder. "

In this way, Hunter's collection initially remained in the hands of Everard Home, who sold it to the Royal College of Surgeons of England in 1799 for the ridiculous price of £ 15,000 . The Royal College of Surgeons appointed William Clift (1775-1849), the former assistant and secretary of Hunters, as curator . Under Clift's direction, the museum gained international recognition and attracted visitors from all over the world. At the same time, Clift began copying Hunter's unpublished manuscripts. Everard Home had asked for them to be handed over, and Clift had a premonition that the papers could face an uncertain fate if he handed them over to Home. Clift's premonition came true. As it later turned out, Home used the manuscripts finally handed over to him for his own publications and copied large parts of them verbatim. Years after Home was honored with the prestigious Copley Medal for his scientific achievements , he burned Hunter's manuscripts; only smaller parts of Hunter's extensive records were preserved for posterity, along with Clift's copies. Hunter's specimens are open to the public today in the Hunterian Collection at the Royal College of Surgeons, London.

Even more than Hunter's collections and writings, his students contributed to the survival of his ideas. They spread his approach to scientific surgery to Britain and the United States . Hunter's biographer Moore notes: "Through Hunter's pervasive influence, the future practice of surgery was essentially based on the doctrines of observation, experimentation and the application of scientific evidence." The Royal College of Surgeons recognized Hunter as the "founder of scientific surgery."

Mount Hunter , a mountain on the Brabant Island in Antarctica, is named after him.

Planned television series

In March 2012, the American television broadcaster AMC announced that it would produce a television series about the life of John Hunter. The book The Knife Man. The Extraordinary Life and Times of John Hunter, Father of Modern Surgery by Wendy Moore from 2005. The scripts for this were already written by Rolin James . Sam Raimi and David Cronenberg were to act as producers , with Cronenberg also being discussed as a director for at least the pilot episode. Two years later, AMC announced that production of the series would be discontinued.

Fonts (selection)

- Standalone writings published during Hunter's lifetime

- The Natural History of the Human Teeth: Explaining their Structure, Use, Formation, Growth, and Diseases. London 1771, Google Books .

- A Practical Treatise on the Diseases of the Teeth; Intended as a supplement to the Natural History of Those Parts. London 1778, online .

- A Treatise on the Veneral Disease. London 1786, Google Books .

- Later publications

- John Hunter's Natural History of Teeth and Description of the Diseases. Translated from English. Leipzig 1780.

- A Treatise on the Blood, Inflammation and Gun-shot Wounds, by the Late John Hunter. London 1794.

- The Works of John Hunter. Edited by James F. Palmer, 4 volumes, London 1835–1837, Google Books .

- Observations and Reflections on Geology. London 1859, Google Books .

- Essays and Observations on Natural History, Anatomy, Physiology, Psychology and Geology. Edited by Richard Owen , 2 volumes, London 1861, Google Books, volume 1 , volume 2 .

- Letters from the Past, from John Hunter to Edward Jenner. Edited by EH Cornelius and AJ Harding Rains, London 1976.

- The Case Books of John Hunter FRS. Edited by Elizabeth Allen, JL Turk and Sir Reginald Murley, London 1993.

- Directory of Scriptures

For a complete listing of the writings of John Hunter, Qvist, John Hunter , Chapter "Publications", pp. 56-66 is authoritative. Qvist organizes the publications first thematically and then chronologically.

literature

- Older representations

- Jessé Foot: The life of John Hunter . London 1794 ( Digitized at Google Books ; Jessé Foot was one of Hunters' rivals and so his portrayal is marked by a deep dislike for him. Foot depicts Hunter as a bad-tempered contemporary, relativizes his achievements and claims that Hunter did his medical works did not write myself).

- Everard Home : A Short Account of the Life of the Author . In: John Hunter: A Treatise on the Blood, Inflammation and Gun-shot Wounds . London 1794, pp. Xiii – lxvii ( digitized from the Internet Archive ).

- Drewry Ottley: The Life of John Hunter, FRS London 1835 ( digitized from Google Books ).

- George Thomas Bettany: Hunter, John (1728-1793) . In: Sidney Lee (Ed.): Dictionary of National Biography . Volume 28: Howard - Inglethorpe. , MacMillan & Co, Smith, Elder & Co., New York City / London 1891, pp. 287 - 293 (English, (here via the English edition of Wikisource )).

- Newer representations

- Jessie Dobson: John Hunter . Edinburgh 1969, ISBN 0-443-00647-4 .

- John Kobler: The Reluctant Surgeon. A Biography of John Hunter . London 1960.

- Wendy Moore: The Knife Man. The Extraordinary Life and Times of John Hunter, Father of Modern Surgery . London 2005, ISBN 0-593-05209-9 .

- George Qvist: John Hunter 1728-1793 . London 1981 (In addition to five short biographical chapters, Qvist's presentation also contains a number of chapters on the various medical and scientific sub-areas of Hunter's work. It also contains a list of writings. It should be emphasized that Qvist is one of the few physicians among Hunter's biographers.).

- Barbara I. Tshisuaka: Hunter, John. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , p. 644 f.

- Literary processing

- Garet Rogers: Lancet . New York 1956 (published in the European edition under the title Brother Surgeons ).

- Hilary Mantel : The giant O'Brien . Cologne 2013 (Original: The Giant, O'Brien . London 1998).

Web links

- Literature by and about John Hunter in the catalog of the German National Library

- John Hunter , in: Whonamedit? A dictionary of medical eponyms

Individual evidence

- ^ The East Kilbride parish registry gives February 13, 1728 as the date of birth; Hunter himself celebrated his birthday on February 14th. The Royal College of Surgeons of England takes the latter date as its birthday, while the Hunterian Society celebrates Hunters' birthday on February 13th. George Qvist, John Hunter 1728–1793 , London 1981, p. 1, there also a copy of the extract from the parish register, ibid. P. 3.

- ↑ Reminiscences of Dorothea Baillie , in: The Hunter-Baillie Collection, Volume 2, p. 1 and Volume 6, p. 18. Quoted here from Wendy Moore, The Knife Man. The Extraordinary Life and Times of John Hunter, Father of Modern Surgery , London [u. a.] 2005, p. 16.

- ↑ “he was incapable of putting six lines together grammatically into English”. Jessé Foot, The life of John Hunter , London 1794, p. 60.

- ^ Article in European Magazine of 1782, reprinted in John Abernethy, Physiological Lectures , London 1825, pp. 341–352. Quoted here from Wendy Moore, The Knife Man. The Extraordinary Life and Times of John Hunter, Father of Modern Surgery , London [u. a.] 2005, p. 17.

- ↑ On the flourishing business of the London grave robbers in the 18th century cf. John Kobler, The Reluctant Surgeon. A Biography of John Hunter , Garden City, New York 1960, pp. 61-66, and Moore, The Knife Man , pp. 38-41.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , pp. 37f.

- ↑ See Jessie Dobson, John Hunter , Edinburgh 1969, pp. 21f.

- ↑ On the bladder stone incision in the 18th century cf. Moore, The Knife Man , pp. 46–46. On the method practiced by Cheselden, ibid., P. 50f. and Kobler, The Reluctant Surgeon , p. 71.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , pp. 50f.

- ^ "More important, however, than any manual skills he gleaned, Hunter benefited from Cheselden's singular approach to his craft. Almost any other surgeon of the time would have taught his pupil strict reverence for the ancient methods and theories, while firmly cautioning against any challenge to established ways. Cheselden, conversely, was eager to observe and to experiment, […] willing to learn from his anatomical pursuits […], and adaptable enough to amend his methods accordingly. "Moore, The Knife Man , p. 51.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 51.

- ↑ a b Kobler, The Reluctant Surgeon , p. 72.

- ↑ "[pot] relied as much as possible on the restorative powers of nature, a principle did FORMED the corner stone of John's medical philosophy" Kobler, The Reluctant Surgeon , S. 73rd

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 55.

- ↑ On this and the following cf. Moore, The Knife Man , pp. 57-61 and Kobler, The Reluctant Surgeon , pp. 81-83.

- ↑ See Moore, The Knife Man , p. 58.

- ↑ History of St. George’s ( Memento from September 9, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ) , on the St. George's Hospital website, accessed on September 10, 2011.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 61.

- ^ Kobler, The Reluctant Surgeon , p. 97.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 77.

- ↑ A more detailed description of the experiment carried out by Hunter in 1758 can be found in Moore, The Knife Man , pp. 81f.

- ↑ Cf. Reginald S. Lord: The white veins: conceptual difficulties in the history of the lymphatics , in: Medical History 12, 2 (1968), pp. 174-184, ISSN 0025-7273 , PMID 4875196 , PMC 1033802 ( free full text).

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 88.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 89.

- ↑ Cf. on this and the following Moore, The Knife Man , pp. 92–94.

- ↑ “It is contrary to all the rules of surgery […] to enlarge wounds […]. No wound, let it be ever so small, should be made larger, excepting when preparatory to something else. “ The works of John Hunter , ed. by James Palmer, 4 volumes, London 1835, here volume 3, p. 549.

- ↑ Cf. on this and the following Moore, The Knife Man , pp. 97f.

- ^ Kobler, The Reluctant Surgeon , p. 132 and Moore, The Knife Man , p. 102.

- ^ Kobler, The Reluctant Surgeon , p. 132.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 109.

- ^ Kobler, The Reluctant Surgeon , p. 140.

- ↑ Ullrich Rainer Otte: Jakob Calmann Linderer (1771-1840). A pioneer in scientific dentistry. Medical dissertation, Würzburg 2002, p. 20.

- ^ Kobler, The Reluctant Surgeon , p. 141.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 107.

- ^ Kobler, The Reluctant Surgeon . P. 142.

- ↑ On this and the following cf. Moore, The Knife Man , pp. 121-123.

- ↑ “They made an incongruous pair - Anne taller, with her blonde, willowy grace, her gentle breeding and devotion to the arts; John, plain as salt, fourteen years older, heavyset and disheveled, ill-read, unused to the amenities of the salon, forever preoccupied by the problems of the dissecting room and the sick ward, whose interest in nightingales went no further than wanting to know how their insides were put together. "Kobler, The Reluctant Surgeon , p. 144.

- ↑ Qvist, John Hunter , p. 21 and Moore, The Knife Man , p. 117.

- ↑ George Thomas Bettany: Hunter, Anne . In: Sidney Lee (Ed.): Dictionary of National Biography . Volume 28: Howard - Inglethorpe. MacMillan & Co, Smith, Elder & Co., New York City / London, 1891, pp 284 - 285 (English).

- ↑ See Moore, The Knife Man , pp. 126–130.

- ^ S. Gloyne: John Hunter , Edinburgh 1950.

- ^ EA Gray: Portrait of a Surgeon , London 1952.

- ^ Drewry Ottley, Life of John Hunter , in: The Works of John Hunter, ed. by JF Palmer, London 1835, Volume 1, p. 47.

- ^ Sir d'Arcy Power, John Hunter: A Martyr to Science , in: Selected Writings 1877–1930, Oxford 1931.

- ^ J. Adams, Memoirs of the Life and Doctrines of the late John Hunter, Esq. , London 1817.

- ^ FH Butler, John Hunter , in: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 9th edition, Edinburgh 1881, Volume 12, Se. 385-391.

- ^ S. Paget, John Hunter , London 1897.

- ^ GC Peachey, A Memoir of William and John Hunter , Plymouth 1924.

- ^ Qvist, John Hunter , p. 51.

- ^ Qvist, John Hunter , pp. 46f.

- ↑ "But as I have produced in myself a chancre from a gonorrhea that point is now settled." Royal College of Surgeons of England Library, MS 0007/1/7/2/390, quoted here from Caroline Grigson, Anne Hunter's life , in this. The Life and Poems of Anne Hunter. Haydn's Tuneful Voice, Liverpool 2009, p. 29, note 66.

- ↑ Grigson, Anne Hunter's life , p. 34 refers to the fact that the painting given by Selwyn Taylor, John Hunter and his painters , in: Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England 1993, p. 5, was dated between 1775 and 1778 cannot be correct because Robert Home was in Italy at the time. It bases its dating on EB Day, Without Permit , unpublished typewriter manuscript (around 1920), British Library, Mss Eur Photo Eur 331 and WD 4431 (Additional) / 20.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 170.

- ↑ See Moore, The Knife Man , p. 172.

- ^ Kobler, The Reluctant Surgeon , p. 164.

- ^ Sir Arthur Porritt, John Hunter: Distant Echos , in: Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England 41 (1967), p. 10.

- ^ So Moore, The Knife Man , p. 4.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , pp. 5f.

- ↑ On these animal experiments cf. Qvist, John Hunter , pp. 109 and 110f. and Moore, The Knife Man , p. 8.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 11.

- ^ Qvist, John Hunter , p. 111.

- ↑ "It is nevertheless true that Hunter was the first to apply a ligature to the femoral artery for spontaneous popliteal aneurisms in accordance with distinct scientific principles discovered and demonstrated by the scientific method of observation and experiment." Qvist, John Hunter , p. 112 .

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 148.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 151.

- ↑ "His labs would make him a pioneer, though rarely Recognized As examined in the discipline did would become established in the Following century as biology." Moore, The Knife Man , p.151.

- ↑ László A. Magyar, John Hunter and John Dolittle , in: Journal of Medical Humanities 15, 4 (1994), pp. 217-220.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 153.

- ↑ Tom Hickman, Death - A User's Guide , London 2002, pp. 100-101.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 213.

- ^ Jessie Dobson, John Hunter's Animals , in: Journal of the History of Medicine, October 1962, p. 479.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 239.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 249.

- ↑ For more detailed information on Hunter's patients, see a. Qvist, John Hunter , pp. 167-174.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 228.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 231.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , p. 232.

- ^ Moore, The Knife Man , pp. 234f.

- ↑ Everard Home, A Short Account of the Life of the Author , in: A Treatise on the Blood, Inflammation and Gun-shot Wounds, by the Late John Hunter, London 1794, pp. Lxii – lxv.

- ↑ “What! Buy preparations! Why, I have not got money enough to purchase gunpowder, "Ottley, Life of John Hunter , p. 137.

- ^ Ottley, Life of John Hunter , p. 142. Kobler, The Reluctant Surgeon , p. 312 gives 1800 as the year of sale.

- ^ Kobler, The Reluctant Surgeon , p. 317.

- ↑ Clift later wrote in his report (Note on the Preservation of the Hunterian Observations Before Their Destruction by Sir Everard Home) to the Royal College of Surgeons: “having a kind of presentiment that if they were removed to his house some accident might befall them “Quoted here from Moore, The Knife Man , p. 272.

- ↑ "But through Hunter's pervasive influence, the future practice of surgery would be based largely on the doctrine of observation, experimentation, and application of scientific evidence" Moore, The Knife Man , p. 275.

- ^ "Founder of Scientific Surgery" - so the inscription on a plaque that was put up by the Royal College of Surgeons at Hunter's reburial in Westminster Abbey. See Moore, The Knife Man , p. 275.

- ↑ Brendan Bettinger: David Cronenberg to Direct and Produce Drama Pilot KNIFEMAN About 18th Century Surgeon John Hunter , Collider.com, March 12, 2012, last accessed October 2, 2016.

- ↑ Lesley Goldberg: AMC Passes on Drama Pilots 'Knifeman,' 'Galyntine' , The Hollywood Reporter, October 31, 2014, last accessed October 2, 2016.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Hunter, John |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | British anatomist and founder of scientific surgery |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 13, 1728 or February 14, 1728 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Long Calderwood at East Kilbride , Scotland |

| DATE OF DEATH | October 16, 1793 |

| Place of death | London |