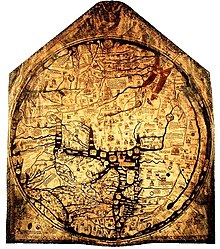

mappa mundi

A mappa mundi (Latin, plural: mappae mundi ) is a medieval world map in the tradition of European cartography . Due to the earlier Ptolemaic tradition, there are some references to the Islamic maps of this time. The chronological end of this type of map lies in the 15th century, when seafaring discoveries and cartography made progress.

Mappa is originally a white, spread out cloth.

General and source value

According to Harvey, over a thousand maps of the world have survived from Europe from the 7th to the 14th century, but these are mostly simple diagrams in which some information has been spatially arranged. They appear, for example, as illustrations for philosophical or scientific treatises.

Mappae mundi are treated as historical sources in Historical Geography , a historical auxiliary science . They should not be measured solely on the basis of whether geographic information is correct based on current knowledge. These maps also serve to determine the geographical knowledge of the time. Anna-Dorothee von den Brincken points out that her current value is not so much scientific as it is in the humanities: It is not about geographical details, but about the ordo in the sense of the worldview. They are to be understood primarily as thematic maps, not as a means of concrete geographic orientation.

prehistory

The forerunners of the medieval world maps are Roman TO maps on which the Tanais ( Don ), Nile , Black and Aegean Seas separate Asia from Europe and Africa , which in turn were separated by the Mediterranean Sea. However, there are no surviving maps from Roman times; therefore the assumption that there was an excellent map tradition in antiquity that perished in the Middle Ages cannot be substantiated. The work of the Greek geographer Claudius Ptolemy (around 150 AD) has only survived as a text, the known maps based on it are modern. The Tabula Peutingeriana (after 330 AD) is a street map. Furthermore, there is said to have been an ecumenical card from Augustus' son-in-law Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa .

Questions

When evaluating medieval world maps, some questions have become common; According to Gervasius, a distinction is made between pictura and scriptura . The pictura , i.e. the picture, the painted thing, should be copied as precisely as possible; in the scriptura , the writing or the map legend, one was freer and could discuss uncertainties.

The geographical orientation is important; While today's maps are usually north (north is "up"), in the European (Christian) Middle Ages maps were mostly geosted because salvation comes from the east. The center of several maps is Jerusalem, the center of the world. Sometimes even the body of Christ is connected to the map so that you can see his head above, feet below and hands on the left and right. In general, you pay attention to the external delimitation of such maps. Political borders are mostly not found, because rulers were only understood to be territorial in the late Middle Ages, according to von der Brincken .

Often two regions are shown particularly large (mostly disproportionate):

- the Holy Land (Palestine) , because of its salvation-historical significance and the many biblical details that one wants to show;

- the region of the map author who knows his own region (residential area or area of origin) better than others.

Traditionally, antiquity and the Middle Ages distinguish (and know) three continents: Europe, Asia, Africa. They are associated with Noah's descendants Jafet , Shem, and Ham . Then there was the question of a fourth continent ( terra australis incognita ), where the authors often settled monsters (“ antipodes ”).

Finally, the drafting of the coastlines and the author's geographical knowledge are quite important. The most accurate representation possible is one extreme, a very schematic representation with three areas (continents) and three oceans separating it is the other ( TO map ). Geographical and - from today's perspective - rather philosophical-speculative ideas flow into the type of presentation.

Sources of the authors

For the contents of the maps, the authors mainly used the literature they could find about distant countries. Often these are the popular and widespread works of the well-known authorities. A distinction must be made according to origin and content:

- Bible history, also important in connection with salvation history;

- classical antiquity together with mythology and fictional literature such as the legend of Alexander ;

- the scientific works of antiquity and the Middle Ages, for example for exotic animals;

- the knowledge as it was to be found in the so-called world chronicles .

Development and well-known examples

According to Harvey and Englisch, it is wrong to see a simple transition from primitive to more elaborate . It's about the origin and the context, but especially about the intended message of a mappa mundi .

The most famous mappae mundi are the

- Mappa mundi d'Albi , the map created in the 8th century is one of the first two non-symbolic and non-abstract world maps;

- the Tabula Rogeriana by the Arab geographer Idrisi from the 12th century,

- 13th century Hereford map , often thought of as the typical Mappa Mundi; it is the largest of these cards still in existence;

- the little London Psalter map from the 13th century,

- the Ebstorf world map from around 1300, the original of which was burned in the Second World War, and

- the 1448 world map by Andreas Walsperger

- Fra Mauro's Mappa Mundi from 1459/60

The Vinland Map is true for most professionals as a forgery.

As early as 1375, the Jewish cartographer Jáfuda Cresques Abraham de Aragón created the so-called Catalan Atlas , the mapa mondí , one of the most famous maps of the Middle Ages, in which a compass rose is drawn for the first time . In it u. a. Marco Polo's journey through Asia and south of the Mediterranean coast travelers with camels on the way to Mali illustrated. The Cresques Abraham de Aragón, who works in Mallorca , has access to both Christian and Islamic sources, which is what makes the Catalan Atlas so unique. The atlas was given to Charles V of France by King Peter IV of Aragon in 1380 .

Together with such maps, the portola maps (sea maps for practical use) point the way to modern maps.

See also

literature

- Anna-Dorothee von den Brincken : Cartographic sources. World, sea and regional maps (= Typology des Sources du Moyen Âge Occidental. 51). Brepols, Turnhout 1988, ISBN 2-503-36000-9 .

- Paul DA Harvey: Medieval Maps. The British Library, London 1991, ISBN 0-7123-0232-8 .

- Hartmut Kugler: Medieval world maps and literary knowledge transfer. To the description of the earth Rudolf von Ems. In: Horst Brunner, Norbert Richard Wolf (ed.): Knowledge literature in the Middle Ages and in the early modern times. Conditions, types, audience, language (= knowledge literature in the Middle Ages. 13). Reichert, Wiesbaden 1993, ISBN 3-88226-555-8 , pp. 156-176.

- Brigitte English: Ordo orbis terrae. The world view in the Mappae mundi of the early and high Middle Ages (= Orbis mediaevalis. 3). Academy, Berlin 2002, ISBN 3-05-003635-4 (also: Hamburg, University, habilitation paper, 2000).

- Rudolf Simek : Earth and Cosmos in the Middle Ages. The worldview before Columbus. Beck, Munich 1992, ISBN 3-406-35863-2 .

Web links

- The Hereford Mappa Mundi ( Memento from January 12, 2012 in the Internet Archive )

- Detailed Mappa Mundi by Fra Mauro (in the article at the bottom)

Individual evidence

- ^ PDA Harvey: Medieval Maps. The British Library, London 1991, p. 19.

- ↑ Von den Brincken: Cartographic sources. 1988.

- ↑ Gerd Spies (Ed.): Braunschweig. The image of the city in 900 years. History and views. Volume 2: Braunschweig's cityscape. Städtisches Museum Braunschweig, Braunschweig 1985, p. 17.