Compass rose

Information on formatting in the article:

Due to the large number of proper names, wind names are highlighted in italics, as in the example, to make them easier to distinguish . Etymological explanations are put in 'angle brackets'.

The Windrose is a graphical means to wind and wind directions or compass display. It is used for orientation on geographical maps, even in the extremely simplified form of an arrow indicating the north direction, and as a compass rose is a common component of compasses .

Even if it plays a subordinate role as a so-called common figure , for example in heraldry , it still serves as a popular and important design element in a variety of contexts.

The designation as "rose" is related to the rather artistic design, as it used to be common in book illumination and maps. Older sources sometimes use the term stella maris ('star of the sea') to refer to the use of the wind rose in nautical science (an overlap with the Marian title Stella maris is possible).

Emergence

The compass rose was originally designed for meteorological purposes and had only a temporary meaning for use in navigation, because for a short time no distinction was made between waypoints and winds. Finally, the classic wind rose with twelve winds was replaced by the modern compass rose (with a division into 8, 16 or 32 segments), which has been continuously developed by seafarers and cartographers since the Middle Ages .

The names of the winds play a decisive role in the long development of the wind rose . The Greeks and Romans based the classification on the name of the winds to indicate the geographical direction. Old wind roses usually had a division into twelve wind directions, sometimes reduced to eight, but could also be expanded to up to twenty-four.

It is not certain when or why the geographic orientation was associated with wind and its direction.

In 1983 the linguist Cecil Brown examined 127 languages in the world. He found that 18% of languages have no terms for directions at all and only 64% name all four directions. It is likely that for the ancient settled peoples local landmarks (e.g. mountains, deserts, settlements) were the first and most immediate markers for general direction ('towards the coast', 'at the hills' etc.). Astronomical quantities, especially the position of the sun at dusk, were also used to denote a direction.

The association of direction with the wind was another source. It was probably the farming peoples who carefully observed the rain and temperature for their crops and were the first to notice the qualitative differences in the winds - some were damp, others dry, some hot, others cold. And they realized that this difference depends on where the wind is blowing from. Local direction names were used to refer to the winches and eventually the winches themselves were given proper names regardless of an observer's position. This was probably driven by seafarers who, despite the lack of landmarks at sea, recognized a particular wind based on its properties under its familiar name. A last step was to use the proper names of the winds, which denote the general names of the cardinal points on the compass rose .

Biblical sources

There are frequent references to the four cardinal points in the Hebrew Bible . The names can probably be traced back to the ancient Israelites who lived in the region of Judea .

Their geographical names denote:

- the east - as Kedem , which is derived from Edom 'red' and indicates the color of the rising dawn or the red sandstone cliffs of the land of Edom in the east;

- the north - as Saphon , after Mount Zaphon on today's Turkish-Syrian border;

- the south - often called the Negev , after the desert of the same name in the south;

- the west with yam d. H. Sea and is synonymous with Mediterranean .

In the Old Testament, cardinal points are equated with winds in several places. 'Four winds' are mentioned in several places in the Bible. Kedem (the east) is often used as the name of a searing wind blowing from the east. There are some passages that refer to the dispersal of people 'to all the winds'.

Greek antiquity

In contrast to the Israelites of that time, the early Greeks had two separate and distinct systems of determining directions and winds, at least for a while.

To define the four cardinal points, astronomical quantities were used:

- Arktus ἄρκtος 'the bear' ( Ursa Major , the Big Dipper ) - for the north

- Anatole ἀνατολή 'sunrise' or eous 'dawn' for the east

- Mesembria μεσημβρία 'noon' for the south

- Dysis δύσις 'sunset' or Hesperus 'evening' for the west

Heraclitus suggests that a meridian between the north (Arctic) and its opposite could be used to separate the east from the west.

Homer already spoke of Greeks who sailed with Ursa Major for orientation. The identification of the North Star as a better indicator of the north direction appears to have arisen a little later (it is said that Thales introduced this and probably learned it from Phoenician sailors).

Separated from the cardinal points, the ancient Greeks had four winds - the anemoi . According to reports, the peoples of early Greece initially observed only two winds - the winds from the north, known as Boreas (βoρ )ας), and the winds from the south, known as Notos (νόtος). But two other winds - Euros (εὖρος) from the east and Zephyros (ζέφυρος) from the west - were soon taken into account.

The etymology of the four ancient Greek wind names is also uncertain.

Boreas may indicate Boros , an ancient variant of Oros 'mountains' that were geographically located in the north. An alternative hypothesis is that Boros means something like 'voracious', another is that it comes from the phrase ἀπὸ τής βoής 'from the noise', referring to the violent and loud noises that accompany it.

Notos likely comes from Notios 'damp', a reference to the warm rain and storms it brings from the south.

Euros and Zephyros seem to come from Eos 'brightness' and zophos 'darkness', undoubtedly references to sunrise and sunset , respectively .

Homer

The ancient Greek poet Homer (approx. 800 BC) refers to four winds with names, the Boreas , Euros , Notos and Zephyros , which are assigned north, east, south and west, respectively, according to the direction from which they blow (four winds version for Homer's compass rose).

At some points in his works Odyssey and Iliad , Homer seems to indicate winds in a different direction, for example one from the north-west (βορέης καὶ Ζέφυρος) or a western south (ἀργεστᾶο Νότοιο). While some saw in the compound expressions an indication that Homer basically only clearly differentiated northern (Boreas) from southern (Notos) winds, others concluded that he differentiated more, possibly known up to eight winds, for which, however, there is no evidence.

Strabo mentioned around 10 BC That some contemporaries assumed due to Homer's ambiguity that he had already anticipated the distinction between summer and winter, as it will only be introduced later by Aristotle. This refers to the fact that sunrise (east) and sunset (west) are not fixed on the horizon and depend on the time of year (in winter sunrise and sunset are further south, in summer further north). In this version, Homer's compass rose then shows six winds:

Boreas (north) and Notos (south) lie opposite each other on the meridian axis,

Zephyros (north-west) and Euros (north-east) diametrically to Apeliotes (south-east) and Argestes (south-west) on diagonal axes .

Referring to Poseidonios , Strabon argues that Homer sometimes used qualitative attributes to mark the direction of the main winds; Homer wrote " stormy Zephyros" and meant the north-west, when he wrote " clear-blowing Zephyros" he meant the west wind, and "argestes Notos" was the clearing south wind, you Leuco-notos. While it may appear that Homer knew of more than four winds, he did not use these attributes systematically enough to allow us to conclude that he also assumed a compass rose divided into six or eight directions. Other classical authors like Pliny the Elder are convinced that Homer did not mention more than four winds.

Hesiod (around 700 BC) gives the four winds in his poetry Theogony (around 735) mythical personification as deities, the Anemoi (Ἄνεμοι), children of the titans Astraios (god of the twilight) and Eos (goddess of the dawn). But Hesiod himself mentions only three winds by name - Boreas , Notus and Zephyros - which he refers to as the "good winds" and the "children of the morning" (which is a little confusing as it can be read as it is all about easterly winds; it is also strange that euros are not listed). Hesiod also refers to other "bad winds", but not by name.

The Greek physician Hippocrates (approx. 400 BC) refers in his writing De aere, aquis et locis ("About air, water and places") to all four winds and does not use their Homeric names, but the The direction from which they blow (Arktos, Anatole, Dysis etc.). He recognized six geographical points - north, south, sunrise and sunset, differentiated according to summer and winter. With north, south and the winter sun positions he defines the limits for the four main winds.

Aristotle

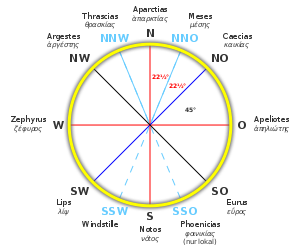

The ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle introduced a wind system with ten to twelve winds in his work Meteorologica (approx. 340 BC). One interpretation of his system is that there are eight main winds: Aparctias (N), Caecias ( NE ), Apeliotes (O), Euros ( SE ), Notos (S), Lips (SW), Zephyros (W) and Argestes (NW) ). Aristotle adds two minor winds , Thrascias (NNW) and Meses (NNE), and states that they have "no opposites". Later, however, Aristotle suggests the Phoenicias , which occurs in some local places, for south-south-east (SSE), but omits the same for south-south-west (SSW). Seen in this way, Aristotle really set up an asymmetrical compass rose with ten winds; two winds are effectively missing.

| North (N) |

Aparctias (ὰπαρκτίας)

(Variant Boreas (βoρέας)) |

uppermost meridian |

| North-Northeast (NNE) | Meses (μέσης) | polar 'rise' |

| Northeast (NE) | Caecias (καικίας) | Summer sunrise |

| East (O) | Apeliotes (ἀπηλιώτης) | Sunrise of the equinox |

| Southeast (SO) |

Euros (εΰρος)

(Variant Euronoti (εὐρόνοtοi)) |

Winter sunrise |

| South-Southeast (SSE) | Calm

(except the local Phoenicias (φοινικίας)) |

|

| South (S) | Notos (νόtος) | lowest meridian |

| South-Southwest (SSW) | Calm | |

| Southwest (SW) | Lips (λίψ) | Winter sunset |

| West (W) | Zephyros (ζέφυρος) | Equinox sunset |

| Northwest (NW) |

Argestes (ἀργέστης)

(Variants: Olympias (ὀλυμπίας), Sciron (σκίρων)) |

Summer sunset. |

| North-Northwest (NNW) | Thrascias (θρασκίας) | polar 'downfall' |

It is worth noting that in the Aristotelian system the old euro is shifted from its traditional position in the far east to Apeliotes (ἀπηλιώτης), synonymous with 'coming from the sun'; The origin of the name becomes even clearer if one uses the Latin translation: Solanus with the word parts Sol 'sun' and anus 'old, aged'.

The old Boreas is only mentioned as an alternative name for Aparctias (ἀπαρκτίας), which means 'from the bear [coming]' and this bear in turn is none other than Ursa Major , the Arctic Circle .

Among the new winds are the Argestes (ἀργέστης) meaning 'clearing' or 'brightening', a reference to the northwest wind that sweeps away the clouds, Argestes variants, Olympias (ἀλυμπίας) and Sciron (σκίρων) are local Athenian names, a Reference to Olympus and the Sciros rock in Megara .

The other winds also seem to be geographically located. Caecias (καικίας) means 'from Caicus [coming]', a river in Mysia , a region in the northeast of the Aegean Sea .

Lips (λίψ) is the Greek name for Libya , southwest of Greece (although an alternative theory links it to λείβω 'Leibo', which has the same word origin as the term for libation , which means 'to pour' because that wind rains brings).

Phenicias (φοινικίας) comes from Phenicia , a landscape southeast of Greece, and Thrascias (θρασκίας) from the name for the Roman province of Thracia (in Aristotle's time Thrace covered a larger area than today, including the north-northwest of Greece).

Finally, Meses (μέσης), which could simply mean 'middle', presumably because it is a side wind (also an intermediate wind).

From the division into main and secondary winds it must be concluded that Aristotle's construction is asymmetrical. In particular, according to this arrangement, the secondary winds are 22½ ° on both sides of the north meridian, while the eight main winds lie one behind the other at 45 °. An alternative hypothesis, however, assumes a more even division into 30 ° segments. As a clue, Aristotle mentions that the eastern and western positions are those taken by the sun on the horizon at different times of the year at dawn and dusk.

With his alphabetical notation, Aristotle stated that at the summer solstice the sun rises at Z ( Caecis ) and sets at E ( Argestes ), at the equinox it rises at B ( Apeliotes ) and sets at A ( Zephyros ) and finally it sets at the winter solstice at Δ ( Euros ) up and at Γ ( Lips ) under.

When applied to a compass rose, Aristotle's explanations reveal four parallels:

- (1) the 'always visible circle', ie the polar circle, the borders of the circumpolar stars

(stars that are so close to the celestial pole that they do not set). (Connection secondary winch IK ) - (2) Summer solstice (connection EZ )

- (3) Equinox (connection AB )

- (4) winter solstice (connection ΓΔ )

Assuming the viewer is in Athens, this construction would result in a symmetrical compass rose with a division into circle segments with central angles of about 30 °. Transferred to a modern compass, the Aristotelian system could be thought of as a twelve-point wind rose with four main wind directions (N, E, S, W), with four winds at the solstices (approx. NW, NE, SE, SW), two Polar winds (approx. NNW, NNE) and two 'no winds = calm' (SSW, SSE)

Aristotle explicitly groups Aparctias (N) and the secondary winds Thrascias (NNW) and Meses (NNE) together as "northern winds" and Argestes (NW) and Zephyros (W) together as "western winds" - and he further emphasizes that both the Winds flowing from the north and west could be classified “generally as north winds = Boreae ”, as they all tend to carry cold air currents with them. Similarly, Lips (SW) and Notos (S) are "south winds" and Euros ( SE ) and Apeliotes (O) are "east winds", but once again both south and east winds are "usually south winds = Notiae “, since they are all relatively warm.

| Aristotle understood that the sun rising in the east warms the east winds longer than the west winds. | |

| With this in mind, Aristotle succeeded in building the ancient Greek two-wind system. |

The exception in this system is Caecias (NO), of whom Aristotle noted that he was "half north and half east", and thus neither predominantly north nor predominantly south. He identifies the only locally occurring Phoenicias (SSO) in a similar way with "half south and half east".

Aristotle goes on to discuss the meteorological properties of winds, e.g. B. that the winds on the NW-SE axis are generally dry, while the NE-SW winds are wet; NE brings heavier clouds with it than SW. N and NNE bring snow. Winds from the entire northwest sector (NW, NE, N) are described as cold, stormy, and cloud-clearing winds that can bring thunderstorms and cyclones with them. In this context, reference should be made to the Medicanes , tropical storm-like storm lows in the Mediterranean, which were only discovered on satellite images in the 1980s due to their spiral-shaped cloud structures.

In addition, Aristotle draws special attention to the periodically occurring Etesiae . These summer winds blow from different directions, depending on the location of the observer.

Aristotle had increased the wind system beyond Homer to ten winds, but left it imbalanced. It was left to subsequent geographers to either add two more winds (SSW and SSE) to make it a symmetrical twelve-wind system (as the navigator Timosthenes will do) or to subtract two winds (NNW and NNE) to make it to convert to a symmetrical eight-wind system (as Eratosthenes will do).

Theophrastus

Theophrastus of Eresos , successor of Aristotle in the Peripatetic school, uses in his works De Signis ("About weather signs ") and De ventis ("About the winds", approx. 300 BC) the same wind system as Aristotle, with only some minor differences: e.g. B. Theophrastus incorrectly wrote Thrascias as 'Thracias' and seemed to differentiate between Apractias and Boreas (perhaps as 'north-west wind' and 'north wind'). In the pseudo-Aristotelian fragment Ventorum Situs (“position of the winds”, often attributed to Theophrastus, but sometimes also Aristotle) there is an attempt to derive the wind names etymologically. Since they are often named for a specific place where they appear to blow from, different places in the Hellenistic world have come up with local names for the winds. The following variants are given in the list of the Ventorum Situs :

- Boreas (N) is named with the variant Pagreus in Mallos , Aparctias is not mentioned.

- Meses (NNO) is given with the variants Caunias in Rhodes and Idyreus in Pamphylia .

- Caecias (NO) is known as Thebanas on Lesbos , in some areas also as Boreas or Caunias .

-

Apeliotes (O) has the names Potameus in Tripoli (Phenicia), Syriandus in the Gulf of Issos Marseus in Tripoli (Libya),

Hellespontias in Evia , Crete , Proconnesus , Teos and Cyrene , Berecyntias in Sinope , and Cataporthmias in Sicily. - Euros (SO) is known as Scopelus in Aegae and Carbas in Cyrene. But sometimes it is also called Phonecias .

- Phonecias (SSO) is not mentioned by its old name, but as Orthonotos , a new name that can be translated as 'True South Wind'.

- Notos (S) is said to be derived from 'unhealthy' and 'moist'.

- Leuconotos (SSW), a previously nameless wind, is named after its cloud-clearing nature and is perhaps given here for the first time.

- Lips (SW) is said to have got its name from the country Libya.

- Zephyros (W) remained unexplained.

-

Argestes (NW) is given as a new variant Iapyx (here unexplained, although in other scriptures the name is connected with Iapygia in Apulia ).

He is also known as Scylletinus in Taranto and elsewhere as Pharangites for Mount Pangaeus. -

Thracias (NNW) is given with the following local variants: Strymonias (in Thrace), Sciron (in Megaris),

Circias (connected to the Mistral in Italy and Sicily ) and Olympias (on Euboea or on Lesbos)

(Note 1: Aristotle called Olympias a variant of Argestes (NW).)

(Note 2: Please note the different spelling compared to Thrascias !)

Timosthenes of Rhodes

The navigator Timosthenes of Rhodes becomes 270 BC. Called to Egypt by Ptolemy II and appointed admiral of the fleet. Timosthenes wrote a ten-volume work entitled On the Ports . It is the best description of the coast of the time. He also prepared an epitome for each book , which contributed to the fact that he remained an often-cited author until late antiquity . 500 years later, the Greco-Roman physician and geographer Agathemeros (c. 250 AD) gave the eight main winds in his Geographia , referring to Timosthenes, who he says had a system of twelve winds by adding four developed to the eight winches in use up until then. (Agathemerus is wrong, of course - Aristotle described at least ten winds, and not eight!)

Timosthenes list (after Agathemeros) contains Aparctias (N), Boreas (not Meses , NNO), Caecias (NO), Apeliotes (O), Euros (SO), Phoenicias alias Euronotos (SSO), Notos (S), Leuconotos alias Libonotos (first mention, SSW), Lips (SW), Zephyros (W), Argestes (NW) and Thrascias alias Circius (NNW).

In many ways, Timosthenes' innovation is a significant step in the development of the compass rose. Depending on when the ventorum situs fragment is dated, Timosthenes can be credited with the further development of Aristotle's asymmetrical ten-point compass into a symmetrical twelve-point compass. He achieved this by introducing Leuconotos alias Libonotos , a wind in SSW that Aristotle and Theophrastus had left out, and assigning the Euronotos to SSE instead of the local Phoenicias (Aristotle already indicated this wind, Theophrastus' Orthonotos is not mentioned here) .

His emphasis on the Italian Circius as the main variant of Thrascias (NNW) could be the first reference to the well-known Mistral in the western Mediterranean. Another important change in Timosthenes is that he moves Boreas from the north position to NNE (replacing Meses - as has become customary with later authors).

Timosthenes is also significant as he is perhaps the first Greek to go beyond treating these winds as a mere meteorological phenomenon and begin to properly view them as points of geographic direction. Timosthenes assigns (according to Agathemeros) geographical regions and peoples to each of the 12 winds (relative to Rhodes):

- Aparctias (N) stands for the Scythians beyond Thrace

- Boreas (NNO) stands for Pontus , Maeotis and the Sarmatians

- Caecias (NO) stands for the Caspian Sea and the Saken

- Apeliotes (O) stands for Bactria

- Euros (SO) stands for the Indus river and the Indians

- Phoenicias or Euronotos (SSO) stands for the Red Sea and Aithiopia (probably Axum )

- Notos (S) stands for the Ethiopians beyond Egypt accordingly ( Nubia )

- Leuconotos alias Libonotos (SSW) stands for the Garamanten beyond the Great Syrte

- Lips (SW) stands for the Ethiopians in the west beyond the Mauroi ( Numidia , Mauri )

- Zephyros (W) lies on the pillars of Heracles , on the border between Africa and Europe

- Argestes (NW) stands for Iberia or Hispania

- Thrascias / Circius (NNW) stands for the Celts .

Modern scholars suspect that Timosthenes may have used the listing of these winds for the epitomes of his lost periplus (nautical navigational aid) (which could explain Agathemeros' eagerness to praise Timosthenes as the "inventor" of the twelve-point wind rose). Timosthenes' geographical list, as shown here, is reproduced almost verbatim centuries later in the work of John of Damascus in the 8th century and in a Prague manuscript from the early 14th century.

In the pseudo-Aristotelian script De Mundo (usually attributed to an anonymous imitator of Poseidonius, probably originated between 50 AD and 140 AD) the names of the winds are almost identical to Timosthenes' names (e.g. Aparctias stands alone in the north, Boreas was moved to NNE , Euronotus replaces Phoenicias and Circius stands as a variant of Thrascias ). The differences between De Mundo and Timosthenes are as follows:

- Libophoenix is introduced as another name for Libonotos ( Leuconotos is not mentioned)

- Two variants of Argestes are mentioned - Iapyx (as in Ventorum Situs ) and Olympias (as in Aristotle; Timosthenes, however, does not mention any variants for this wind)

- As with Aristotle, De Mundo refers to an association of north winds called the Boreae.

Eratosthenes and the Tower of the Winds

When the geographer Eratosthenes of Cyrene in around 200 BC Chr. Recognized that many winds are only slight variations of other winds in higher-level (larger) wind systems, he reduced the (up to then common) twelve winds to eight main winds. Eratosthenes' own work has unfortunately been lost, but Vitruvius reports on it by stating that Eratosthenes came to this conclusion in the course of measuring the circumference of the earth . He found that there really were only eight equally sized sectors and that other winds were only local variants of these eight main winds. If that were true, it would mean that Eratosthenes can be considered the inventor of the eight-point compass rose.

It does not mean anything that Eratosthenes was a disciple of Timosthenes and is said to have primarily built on his work. But it's interesting to see how they differ in this regard. Both recognized that Aristotle's ten-wind system was unbalanced, but while Timosthenes balanced it by adding two winds for a symmetrical twelve-wind system, Eratosthenes subtracted two winds to create an equally symmetrical eight-wind system. System to create.

On practical considerations, Eratosthenes' reduction seems to be a complete success. The famous Tower of the Winds in Athens shows only eight winds instead of the ten by Aristotle or the twelve by Timosthenes. The tower is believed to have been built by Andronikos of Kyrrhos (around 50 BC), but it is generally believed to have been built after 200 BC. Dated (i.e. after Eratosthenes). It shows the eight winds Boreas (not Aparctias , N), Caecias ( SE ), Apeliotes (O), Euros (SO), Notos (S), Lips (SW), Zephyros (W) and Sciron (NW, variant ) in reliefs Argestes ). The reappearance of Boreas as the North Wind in place of Aparctias is noteworthy. In a figurative sense, the reliefs show images of the wind gods, the Anemoi. It is believed that the tower was crowned by a weather vane, as suggested by the 1762 reconstruction .

Romans

The Greek wind system was partly adopted by the Romans under their Greek nomenclature , but also increasingly under new Latin names. The Roman poet Virgil refers in his poem Georgica (approx. 29 BC) to several winds with their old Greek names, albeit with the Latin ending -us instead of Greek -os (e.g. Zephyrus or Eurus ). Also introduces a couple of new Latin names - namely nigerrimus (black) oyster , frigidus (cold) Aquilo, and frigidus Caurus .

Seneca

The Roman writer Seneca , in his work Naturales quaestiones (c. 65 AD) , mentions the Greek names of some of the great winds and goes on to say that the Roman scholar Varro said there were twelve winds.

As stated by Seneca, the Latin names of the twelve winds are:

| North (N) | Sept Trio | |

| North-Northeast (NNE) | Aquilo | |

| Northeast (NE) | Caecias | like the Greek model |

| East (O) | Subsolanus | |

| Southeast (SO) | Vulturnus | also used as a variant with Eurus |

| South-Southeast (SSE) | Euronotus | like Timosthenes |

| South (S) | oyster | used with notus as a variant |

| South-Southwest (SSW) | Libonotus | like Timosthenes |

| Southwest (SW) | Africus | |

| West (W) | Favonius | also used as a variant with Zephyros |

| Northwest (NW) | Corus | with Argestes also used as a variant |

| North-Northwest (NNW) | Thrascias | like the Greek model |

(Derivations of the Latin etymology in the Isidore of Seville section below ↓ ).

Oddly enough, Seneca says that the meridian line emerges from Euronotus (SSW) and not from Auster (S), and that the "highest point" in the north is Aquilo (NNE) and not Septentrio (N).

This could indicate that one was already aware of magnetic declination . This describes the difference between magnetic north (compass north, in this case Aquilo ) and true north (Pole Star, Septentrio ).

Pliny

Pliny the Elder adds in his encyclopedia Naturalis Historia ("Natural History", c. 77 AD) the note that the "Moderns" reduced the winds to eight after he found that twelve was an exaggeration. He lists them as follows: Septentrio (N), Aquilo (NNO), Subsolanus (O), Vulturnus (SO), Auster (S), Africus (SW), Favonius (W) and Corus (NW).

It is noteworthy that Caecias (NO) is not a member of this octet. Instead, Pliny sets the secondary wind Aquilo (NNE) there. It seems that Pliny is aware that Aquilo is a side wind because he says it lies “between the Sept Trio and the summer solstice” (although in a later chapter he places it directly on the summer solstice). In the first version, this means that Pliny 's eight-point compass is asymmetrical. Pliny goes on to mention that " Aquilo is also called Aparctias and Boreas " (the identification with Boreas NNO already made Timosthenes, but the descent of Aparctias from the north is new).

As he continues to discuss side winds , Pliny introduces Caecis again: "... he lies between Aquilo and Subsolanus ", thus de facto restoring his north-east position.

Obviously Pliny reads Aristotle and tries again to place the long lost Meses "between Boreas (= Aquilo ) and Caecis ", that is, at a position that would be found on a modern 32-point compass at north-north-east. In a later chapter Pliny states: " Aquilo is transformed into the Etesiae in summer ". Aristotle had already reported on this periodically occurring wind, now known as Meltemi .

Pliny also mentions the other minor winds , Phoenicias (for SSE and not Euronotus ), Libonotus (SSW) and Thrascias (NNW). Obviously, Pliny had recently read Aristotle and then tried to revive some of the forgotten Aristotelian names. Boreas or Aparctias , Meses , Etesiae , Phoenicias , he even mentions Olympias and Sciron as local Greek winds. Transferred to today's twelve-point compass scheme, however, this undertaking appears rather awkward.

Aulus Gellius

In his work Noctes Atticae (“Attic Nights”, from approx. 159 AD), the Greek-Roman writer Aulus Gellius, originally from Athens, was possibly inspired by the Tower of the Winds in his native city. In any case, he reduces the Latin wind rose from twelve to eight winds, the main winds, for which he gives both the Latin and Greek names as follows:

- N - Septentrio (Latin), Aparctias (Greek)

- NO - Aquilo (Latin), Boreas (Greek)

- O - Eurus (Latin), Apeliotes (Greek), Subsolanus (for Roman sailors)

- SO - Vulturnus (Latin), Euronotos (Greek)

- S - oyster (Latin), Notos (Greek)

- SW - Africus (Latin), Lips (Greek)

- W - Favonius (Latin), Zephyros (Greek)

- NW - Caurus (Latin), Argestes (Greek)

Among the novelties is the disappearance of Caecias from NE (as in Pliny), although he notes in a later note that Caecias is mentioned in Aristotle (but does not give a position). Aquilo or Boreas seems to be established in the NE. Another surprise is the reappearance of Eurus in the east, where he has not been seen since Homer. He seems to use Eurus as a Latin name, to treat the Aristotelian Apeliotes as the Greek equivalent and to reduce Subsolanus to a mere variant 'for Roman sailors'. With Eurus , who is now missing in the SE , Euronotos (previously in the SSO) is promoted to the vacant SE position. Finally a new name appears, Caurus is introduced as a NW wind (this is almost certainly a wrong spelling of Corus , also a NW wind!).

Aulus Gellius gives some information about local winds. He mentions Circius as a local wind in Gaul , known for its dizzying eddies, and with Cercius records his alternate spelling in Hispania (probably a reference to the Mistral ). He also notes Iapyx (which has already been mentioned, but is here first explained as a local wind from Iapygia in Apulia).

And he doesn't forget the periodic regional Etesiae as well as the Prodromi (NW headwinds, Greek πρόδρομοι).

The Vatican table

The Vatican table is a Roman marble anemoscope (wind direction transmitter ) from the 2nd or 3rd century AD and is owned by the Vatican Museums. It is divided into twelve equally sized pages, on each side the classic wind names are carved in both Greek and Latin. The Vatican table lists them as follows:

| wind |

Latin |

Greek | Transcription / Modern Greek | records |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Sept Trio | AΠAPKIAC | Aparkias (ἀπαρκίας) | Greek misspelling. |

| NNO | Aquilo | BOPEAC | Boreas (βoρέας) | as with Timosthenes |

| NO | Vulturnus | KAIKIAC | Caecias (καικίας) |

Vulturnus (usually SO) in the wrong place. Caecias should be here . |

| O | Solanus | AΦHAIωTNS | Apheliotes (ἀφηλιώτης) | Greek misspelling, new Latin name (usually Subsolanus ) |

| SO | Eurus | EYPOC | Eurus (εὖρος) | New Latin name. Vulturnus should be here . |

| SSO | Euro oyster | EYPONOTOC | Euronotos (εὐρόνοtος) | new Latin name (usually Euronotus ) |

| S. | oyster | NOTOC | Notos (νόtος) | |

| SSW | Austroafricus | AIBONOTOC | Libonotos (λιβόνοtος) | new Latin name (usually Libonotus ) |

| SW | Africus | AIΨ | Lips (λίψ) | |

| W. | Favonius | ZEΦYPOC | Zephyros (ζέφυρος) | |

| NW | Chorus | IAΠYΞ | Iapyx (ἰαπύξ) | Latin misspelling (usually Corus ) |

| NNW | Circius | ΘPAKIAC | Thrace (θρακίας) | Greek misspelling, new Latin name (usually Thrascias ), from Timosthenes |

There are several spelling mistakes , both on the Greek ( Aparkias , Apheliotes , Thrakias ) and Latin ( chorus with an h, Solanus without the prefix Sub). The main flaw in the Vatican table is the misplacement of Vulturnus in NE instead of SE , with the result that the old Greek euro now takes its place in the Latin translation. This error will be repeated later. There are also important new Latin names, Austroafricus instead of Libonotus and Circius instead of Thrascias (although the latter was already anticipated by Timosthenes). The old Iapyx from the Ventorum Situs fragment is also making a comeback - in Greek.

Isidore of Seville

Centuries later, after the fall of Rome, Isidore of Seville set out to compile much of the classical knowledge in his encyclopedia Etymologiae (c. 620 AD). In the chapter on the winds, he presented a list that is practically identical to the Vatican table. He also attempted to provide the etymology for each wind name used.

- Septentrio (N) - Isidore connects him with the Arctic Circle. This is known as the "Circle of Seven Stars" and "Ursa Minor". Septentrio can mean 'commander of the seven' and the Pole Star is in fact the main star of the Little Bear (Ursa Minor). An alternative etymology derives the name from septem trione 'seven plow oxen', a reference to the seven brightest stars of the constellation Great Bear (Ursa Major).

- Aquilo (NNO) - Isidore connects it with acqua 'water', but more likely aquilus is 'dark' because it sucks a lot of water from the ground, which leads to dark, heavy rain clouds. Pliny says "the ground announces Aquilo by drying out and oyster by becoming damp for no apparent reason." An alternative interpretation also sees the origin in 'aquilus', but simply connects it with the 'land of darkness', because it blows from the far north.

-

Vulturnus ( NE ) - usually SE , but is accidentally placed in NE by Isidore, as in the Vatican table. Isidore derives his etymology from old tornat , 'thundering high'. Seneca said that "the wind used to be named after a battle (as reported by Livy ) in which the whirlwind drove dirt into the eyes of the Roman soldiers and thus brought about their defeat". Both assumptions are almost certainly wrong. It is probably an old local wind named after the hills on the Volturno southeast of Rome. Others believe that, due to its stormy nature, there is a connection with vulsi 'devastator' (from vellere ).

Volturno itself is named after volvere 'roll', which is related to the Spanish volver 'return'. - Subsolanus (O) - Isidore says he is sub ortu solis 'below the rising sun', in agreement with Aulus Gellius, who further states that the name was coined by Roman sailors.

- Eurus (SO) - derives from the Greek ‹eus = dawn›.

- Euroauster (SSO) - represents the connection between the Eurus and the oyster .

- Oyster (S) - Isidor derives the name from ‹hauriendo aquas = draw water›, a reference to its moisture. First mentioned by Virgil “… [when] oyster pulls itself up black and darkens the sky with cold rain.” Possibly from ‹austerus = hard, hot or shining (from a ray of light)›.

- Austroafricus (SSW) - is derived from the combination of oyster and Africus .

- Africus (SW) - Isidor correctly derives the name from ‹Afrika›, a direct translation of the Greek ‹Lips = Libya›; Greetings from the Romans, because the root ‹Afri› refers to the original name for the Punians (Carthaginians), whose origins the Greeks in turn designated with “Lips”.

- Favonius (W) - Isidore is probably correct with regard to ‹favere = favorable [wind]›. He speaks of it as "the wind that comes in spring, melts the winter frost and revives the flora and fauna". He also connects it with the idea of a "mild wind that clears clouds and softens the summer heat".

- Corus (NW) - Isidore spells him Corus and says he is "the same as Caurus " (the cold Caurus , already mentioned by Virgil, but treated differently from Vitruvius). Isidore associates it with a “choir of dancers who surround themselves with heavy clouds and hold them tight”. Aulus Gellius had said something similar before, but in relation to Caecias , a NE wind. Others have associated Corus with 'covering, concealing' because they refer to it as clouds or maybe rain?

- Circius (NNW) - Isidor sees the origin of the name in the terms ‹circular› or ‹biegen› and interprets his name (perhaps a little confusing) because it ‹ turns into the Corus ›. Pliny and Aulus Gellius had already identified the Circius as Mistral - Pliny called it the "violent wind from Narbonne that drives the waves to Ostia ", while Aulus Gellius spoke of a local wind in Gaul, known for its dizzying eddies, and notes its alternative spelling Cercius in Hispania. Isidore speaks of Gallicus with the Spanish name because it originates in Gaul.

Vitruvius's 24-point compass rose

Vitruvius wrote of the winds in the late 1st century BC. BC and thus before the aforementioned authors such as Seneca, Pliny, Aulus Gellius etc. His system of winds should be considered separately, since Seneca relies on Varro, which was written before Vitruvius, in his representation of the twelve-wind system, while Vitruvius' system is independent distinguished and deserves to be treated separately.

Vitruvius mentions in the first volume of his work De architectura libri decem ("Ten books on architecture", approx. 15 BC) in a rather appreciative way the reduction of the winds from twelve to eight main winds by Eratosthenes. But Vitruvius then goes on to state that there are many other winds that differ only slightly from the predominant eight, which in the past have been mentioned by a separate name. Vitruvius quickly determined two variants on both sides of the eight main winds, resulting in a compass rose made up of 24 winds.

Although it may seem easier to draw the 24 winds equidistant 15 ° from each other, using modern half and quarter wind notation this way they are much easier to list. In the following table, the main winches are highlighted in italics:

| N | Sept Trio | S. | oyster | |

| N to O | Gallicus | S by W | Altanus | |

| NNO | Supernas | SSW | Libonotus | |

| NO | Aquilo | SW | Africus | |

| ONO | Boreas | WSW | Subvesperus | |

| O to N | Carbas | W to S | Argestes | |

| O | Solanus | W. | Favonius | |

| O to S | Ornithiae (occurring intermittently) | W to N | Etesiae (occurring periodically) | |

| OSO | Eurocircias | WNW | Circius | |

| SO | Eurus | NW | Caurus | |

| SSO | Vulturnus | NNW | Corus | |

| S to O | Leuconotus | N to W | Thrascias |

Many of the names on Vitruvius's list had previously appeared elsewhere. Changes worth mentioning include the introduction of Gallicus (probably the Mistral ) and Supernas (probably a local wind on an alpine lake) in the extreme NE, the move from Aquilo (old NNE) to NE, almost like Pliny.

Old Boreas (now separated from Aquilo ) has been moved further east - never before has it been moved so far from its former place to the north. Caecias is disappearing completely from NO (although he appears in some counts on Vitruvius's list and will soon make his comeback at Seneca). Carbas , as already mentioned an SE variant from Cyrene, is positioned in the northeast quadrant . The Latin Vulturnus is rightfully located in the southeast next to its Greek variant Eurus . The Greek Argestes is given here separately, in the vicinity of Favonius in the west, but below its usual north-western quadrant.

Leuconotus , previously a variant for Libonotus , is detached and moved to the southeast quadrant; to a place where usually Euronotos or EUR oyster , which seem to be but now entirely disappeared were found. There is, however, a similar-sounding name nearby, Eurocircias in the southeast, which could be identical to the biblical Euroaquilo .

Among other things, it is worth mentioning that Solanus is not listed with the prefix Sub and the wind Caurus (mentioned later in Aulus Gellius) is inserted between Corus and Circius (together with the ancient Thrascias , which is given a separate position above). It is also important that Caurus and Corus are treated differently from each other and not just as a spelling mistake by the other. Altanus is likely a local reference to a sea breeze.

The impression can arise that Vitruvius only wants the names of winds and their respective positions to be summarized in a single long list, approving the formation of redundancies , in a single system. The shifts of some ancient Greek winds ( Boreas , Eurus , Argestes , Leuconotus ) to non-traditional positions (sometimes even wrong quadrants), could reflect the relative position of Greece to Italy - or simply indicate that Vitruvius did not care too much laid the day and roughly assigned their names just to get a nice, symmetrical system with two side winds for each main wind. But you can also see almost a hint of mockery in its construction, as if it were trying to ridicule more complicated wind systems that go beyond the basic eight winds.

Even if it is mostly ignored, Vitruvius' list of the 24 Winds occasionally reappears. Georgius Agricola last spoke out in favor of Vitruvius's list in his book of metal science De re metallica (1556).

Coincidentally, 24-point compass roses were used in sky maps of astronomy / astrology and Chinese geography, but these are not related to Vitruvius.

Medieval transition period

The ancient world ended with the unsolved dispute between Eratosthenes' eight-point wind rose and the twelve-point wind rose according to Timosthenes. Simply put, it seemed that the classically minded geographers preferred the twelve-wind system while the more practical ones preferred the eight-wind system. Only very few sources are available from the early Middle Ages. Around the year 620 the encyclopedia Etymologiae of Isidore of Seville appeared, who as guardian of classical knowledge preserved the twelve wind directions of Timosthenes for posterity.

Charlemagne

The Franconian chronicler Einhard claimed in his biography " Vita Karoli Magni " (approx. 830) that Charlemagne himself adopted the classic twelve-wind system, using the Greco-Latin names with a number of completely new Germanic names of his own invention replaced. He lists Karl's nomenclature with the corresponding Latin names from Isidor's list as follows:

| N | Nordroni | S. | Sundroni | |

| NNO | Nordostroni | SSW | Sundvuestroni | |

| NO | East Nordroni | SW | Vuestsundroni | |

| O | Ostroni | W. | Vuestroni | |

| SO | East Sundroni | NW | Vuestnordroni | |

| SSO | Sundostroni | NNW | North Vuestroni |

Interestingly, Karl's structure solves the problem with the side winds (e.g. NNE versus NE) through the word order - northeast and east-north - and thus does not give any priority over the others (consequently NNE moves closer to ONE, while NO itself is missing). The Franconian suffix ‑roni denotes adjectives indicating the direction “from where”. Karl's name nordroni means “coming from the north” and, in combination with wind (wint), denotes the “north wind”. However, its subdivisions were just as unsuccessful as its related nomenclature.

The main winds in Karl's name system, which is mapped out for example in Old Norse with the dwarfs Norðri, Suðri, Austri and Vestri of Nordic mythology , can be found as the main directions (north, east, south and west) in most western European languages, regardless of the Belonging to the Germanic ( German , Dutch , English etc.) or Romance language branch ( French , Italian , Spanish , Portuguese , Romanian ). In the French language as a mediator for Italian, Spanish and Portuguese, however, they were only accepted in the 12th century, when Anglo-Saxon words increasingly found their way into French among the descendants of Wilhelm the Conqueror .

Arabic translator

In the early Middle Ages, Arab scholars came into contact with the Greek works. Yahya ibn al Bitriq and Hunayn ibn Ishaq translated Aristotle's “Meteorologica” and scholars like Ibn Sina and Ibn Ruschd commented on and expanded them for their own systems. A surviving Arabic text from the 9th century (pseudo- Olympiodoros , translated by Ḥunain ibn Isḥāq ) is not authentic, as a comparison with the Greek original shows; however, it contains the following Arabic names for the 12 Greek winds:

| N | šimāl | S. | janūb | |

| NNO | mis | SSW | hayf | |

| NO | nis | SW | hur jūj | |

| O | şaban | W. | dabūr | |

| SO | azyab | NW | mahwa | |

| SSO | nu'āmā | NNW | jirbiyā |

The sailor's compass rose

The sudden appearance of the portolan cards at the beginning of the 13th century in the Mediterranean, originally in Genoa , but soon in Venice and also in Mallorca , suggests that they were based on sailing instructions that were long before in the pilot books (portolani) of the Seafarers in the Mediterranean were written down. Measurements with the nautical magnetic compass , which was created almost at the same time, were entered together with directions in maps of an eight-point compass system. The cardinal points were given with the following names:

| N | Tramontana | S. | Ostro | |

| NO | Greco | SW | Libeccio or Garbino | |

| O | Levant | W. | Poniente | |

| SO | Scirocco | NW | maestro |

Of these eight main winds, a 16-point wind rose with secondary winds (NNE, ONE etc.) could be constructed, which merely combines the names of the main winds (e.g. NNE would represent the Greek Tramontana , ONO the Greek Levant etc.). In 32-point wind roses, as they can already be found on maps from the early 13th century, the distances were halved again and the names of the 'quarter winds' that resulted could also be generated simply by combining the names of the main winds.

The names of the eight winds of this compass rose apparently go back to the Italian-colored ' lingua franca ' in the Mediterranean region during the High and Late Middle Ages. Of the eight winds, only two can be traced back to previous classic winds, Ostra (S) from the Latin oyster and Libeccio (SW) from the Greek Lips - but the others seem to have largely been designed independently.

The names Levante (O) from Latin ‹levare = to rise, so to rise› and Poniente (W) from ‹[de] ponere = to set, so set› were of course associated with the position of the sun, but etymologically very different from the pictures of the ancient names that refer to lightness, darkness or the sun itself, but explicitly do not refer to the verbs rising or setting. Tramontana (N), Italian for ‹over the mountains›, probably refers in the name to the Alps in northern Italy, but has nothing to do with the classic Aparctias-Septentrio (although there is a delicate connection with the ancient Greek Boreas , which im Venetian usage was preserved, as well as in the Bora of the Adriatic ). The Maestro is, as already mentioned, the equivalent of the Mistral in the western Mediterranean, a wind of as early as the Latin Windrose Circius was specified, the name here but is new.

Two Arabic words catch the eye: Scirocco (SO) from the Arabic ‹al-Sharq = east› and the variant Garbino (SW) from the Arabic ‹al-Gharb = west› - both are translated as rising or setting. There is also the riddle of Greco (NO). Since Greece is in southeastern Italy, this strongly suggests that Greco's name was given in the southern Mediterranean, very likely in the 10th or 11th century in Arab Sicily (the Byzantium- held provinces of Calabria and Puglia were in the northeast of the Arab Sicily).

The Italian seafarers of the Middle Ages did not acquire a substantial part of their sailing knowledge from their Roman ancestors, but from Arab seafarers via Arab-Norman Sicily . While sailors are likely to have been completely indifferent to the sources of their knowledge, scientists trained in the classics of Isidore and Aristotle were not so easily won over. The classic twelve-point compass rose was taught in the academies until well into the 15th century. B. in Peter von Ailly's astronomical-geographic writing “Imago Mundi” using Isidor's version.

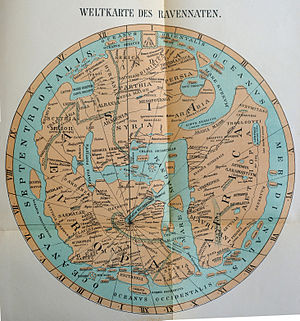

Several school-designed ' mappa mundi ' helped to introduce the classic twelve-point compass rose. Among these are the 'mappa mundi' from the Beatus of Saint-Sever from the 8th century ( map ), the Tabula Peutingeriana from the Reichenau from the 10th century, ( map ) the 'mappa mundi' of Henry of Mainz from the 12th century, the Ebstorf world map from the 13th century ( map ) and the world map by Ranulf Higden from the 14th century. ( Map )

Many postage cards show respect for the classical and spiritual authorities by including pointers for the twelve classical winds - not in the form of a compass rose, rather the cartographers wrote names or initials of the winds in small circular areas that they placed on the edges of the card so that they didn't bother.

As early as 1250, the English scholastic Matthäus Paris tried to reconcile the twelve classical winds that were taught to him with the 'new' wind rose from the Mediterranean region in an appendix to documents, the “Liber Additamentorum”, which was written separately from his main work “Chronica Maiora”.

In a first step, Matthäus assigned the twelve classic names to N, E, S, W and the secondary winds (NNE, ONO, OSE etc.), so that the main diagonals NE, SE, SW and NW remained empty. Thus Septentrio falls on N, Aquilo on NNE, Vulturnus on ONO, Subsolanus on O, Euros on OSE, Euroauster on SSE, Auster on S and so on. (This assignment is indeed used by many authors to explain the classic twelve-wind system in modern terms, but not in this article).

In a second step, he pulled 16 classic-sounding names for all 16 winds of the wind rose out of his hat. In his draft, scribbled rather sloppily in the corner of a manuscript, he seemed to be considering the following list:

| N | Aquilo = Septentrio | S. | Oyster meridionalis | |

| NNO | Boreas aquilonaris | SSW | Euro oyster africanus | |

| NO | Vulturnus borealis | SW | Euros procellosus | |

| ONO | Boreas orientalis | WSW | Africus occidentalis | |

| O | Subsolanus , Calidus and Siccus | W. | Zephyros blandus = Favonius | |

| OSO | Euros orientalis | WNW | Chorus occidentalis | |

| SO | Euro-nothus | NW | Circius choralis | |

| SSO | Euro oyster , Egipcius ? | NNW | Circius aquilonaris |

But Matthew apparently did not pursue this thought further and did not go beyond the notation of these names.

In his 1558 atlas , the Portuguese cartographer Diogo Homem made a final attempt to reconcile the classical twelve with the eight sailors' winds by assigning eight of the twelve to the main winds of the compass, and the remaining four (NNW, NNE, SSE and SSW) to side winds.

| N | Tramontana = Septentrio | S. | Ostro = notus or oyster | |

| NNO | Tramontana-Greco = Boreas or Aquilo | SSW | Libeccio-Ostro = Libonotus | |

| NO | Greco = Hellespontus or Caecias | SW | Libeccio = Lips or Africus | |

| O | Levante = Euros or Subsolanus | W. | Poniente = Zephyros or Favonius | |

| SO | Scirocco = Vulturnus | NW | Maestro = Caurus or Corus | |

| SSO | Scirocco-Ostro = Euronotus | NNW | Tramontana-Maestro = Circius |

Diogo Homem's assignment of the 12 ancient names to the modern compass corresponds exactly to the assignment as it was used throughout the article.

use

Examples for use in cards and fonts

The compass rose as a design element

The compass rose is an old design element on buildings and is often attached to the top of the roof. It is used for orientation and illustration of the compass direction , in conjunction with a wind vane to display the wind direction.

It can be found on facades such as the ' Tower of the Winds ' in Athens, on places such as the 'Place of the Wind Rose' in the Roman ruins of Thugga or St. Peter's Square in Rome , as a sculpture in front of the seat of the North Atlantic Council in Brussels ; even on floors like the Padrão dos Descobrimentos (Monument to the Discoveries) in Lisbon and sometimes even in normal family houses.

As a decoration on textiles, it is certainly not only used in the symbol on the NATO flag , where it stands for 'for the common course of member states towards peace'.

Pavement mosaic in Freiburg im Breisgau

The compass rose in heraldry

In heraldry, the compass rose is a so-called 'common figure'. It does not occur often and is represented by superimposed stars . The north direction is rarely highlighted.

Compass rose in the upper coat

of arms of the coat of arms of the Northwest TerritoriesNordwestuckermark ,

compass rose with emphasis on the northwest directionSchönefeld ,

north direction represented by a split lily

Comparison table of wind names

The picture on the left shows the “Anemographia” ( description of the wind ) by Johannes Janssonius from Volume 5 of the “Atlas Novus Sive Theatrum Orbis Terrarum” from 1652.

The concentric rings indicate the directions in 6 languages. North is inclined 45 degrees to the left.

The following table summarizes the development of the names of the winches for classical antiquity and the early Middle Ages in chronological order. The comparison with Vitruvius's 24-point compass rose is dispensed with at this point, because its representation is too idiosyncratic and not compatible with the rest of the table.

Changes in name or position to the previous version are highlighted in bold.

| Greeks | N | NNO | NO | O | SO | SSO | S. | SSW | SW | W. | NW | NNW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardinal points |

Arctos (ἄρκtος) |

Anatole (ἀνατολή) |

Mesembria (μεσημβρία) |

Dysis (δύσις) |

||||||||

| Homer (4-winch version) |

Boreas (βoρέας) |

Euros (εὖρος) |

Notos (νόtος) |

Zephyros (ζέφυρος) |

||||||||

| Homer (6-winch version) |

Boreas | Euros | Apeliotes | Notos | Agrestes | Zephyros | ||||||

| Aristotle |

Aparktias or Boreas |

Meses | Kaikias | Apeliotes |

Euros or Euronoti |

Calm ( Phoinikias only local) |

Notos | Calm | Lips | Zephyros |

Argestes , (locally Olympias or Skiron ) |

Thraskias |

|

Aristotle (in Greek ) |

ἀπαρκτίας, βoρέας |

μέσης | καικίας | ἀπηλιώτης | εὖρος, εὐρόνοtοi |

(φοινικίας) | νόtος | λίψ | ζέφυρος | ἀργέστης, (ὀλυμπίας, σκίρων) |

θρασκίας | |

| Theophrastus |

Aparktias or Boreas |

Meses | Kaikias | Apeliotes | Euros | ( Phoinikias ) | Notos | Lips | Zephyros | Argestes | Thrace | |

Wind names of the Ventorum situs |

Boreas | Meses | Kaikias | Apeliotes | Euros | Orthonotos | Notos | Leukonotos | Lips | Zephyros |

Iapyx or Argestes |

Thrace |

| Timosthenes | Aparktias | Boreas | Kaikias | Apeliotes | Euros | Euronotos | Notos |

Leukonotos also known as Libonotos |

Lips | Zephyros | Argestes |

Thraskias or Circius |

| Wind names of the font 'De Mundo' |

Aparktias | Boreas | Kaikias | Apeliotes | Euros | Euronotos | Notos |

Libonotos or Libophoenix |

Lips | Zephyros |

Argestes or Iapyx , or Olympias |

Thraskias or Circius |

| Wind names on the 'Tower of the Winds' |

Boreas | Kaikias | Apeliotes | Euros | Notos | Lips | Zephyros | Skiron | ||||

| Romans | N | NNO | NO | O | SO | SSO | S. | SSW | SW | W. | NW | NNW |

| Seneca | Sept Trio | Aquilo | Caecias | Subsolanus |

Vulturnus or Eurus |

Euronotus |

Oyster or notus |

Libonotus | Africus |

Favonius or Zephyros |

Corus or Argestes |

Thrascias |

| Pliny | Sept Trio |

Aquilo or

Boreas or Aparctias |

Caecias | Subsolanus | Vulturnus | Phoenicias | oyster | Libonotus | Africus | Favonius | Corus | Thrascias |

| Aulus Gellius |

Septentrio Aparctias |

Aquilo Boreas |

Eurus Apeliotes Subsolanus |

Vulturnus Euronotus |

Auster notus |

Africus Lips |

Favonius Zephyros |

Caurus Argestes |

||||

| Wind names of the 'Vatican table' |

Septentrio Aparkias (ἀπαρκίας) |

Aquilo Boreas (βoρέας) |

Vulturnus Kaikias (καικίας) |

Solanus Apheliotes (ἀφηλιώτης) |

Eurus Euros (εὖρος) |

Euro oyster Euronotos (εὐρόνοtος) |

Oyster Notos (νόtος) |

Austroafricus Libonotos (λιβόνοtος) |

Africus Lips (λίψ) |

Favonius Zephyros (ζέφυρος) |

Chorus Iapyx (ἰαπύζ) |

Circius Thrace (θρακίας) |

| Isidore of Seville | Sept Trio | Aquilo | Vulturnus | Subsolanus | Eurus | Euro oyster | oyster | Austroafricus | Africus | Favonius | Corus | Circius |

| middle Ages | N | NNO | NO | O | SO | SSO | S. | SSW | SW | W. | NW | NNW |

| Charlemagne | Nordroni | Nordostroni | East Nordroni | Ostroni | East Sundroni | Sundostroni | Sundroni | Sundvuestroni | Vuestsundroni | Vuestroni | Vuestnordroni | North Vuestroni |

| Hunayn ibn Ishaq | šimāl | mis | nis | şaban | azyab | nu'āmā | janūb | hayf | hur jūj | dabūr | mahwa | jirbiyā |

| Diogo Homem | Tramontana | Greco-Tramontana | Greco | Levant | Scirocco | Ostro Scirocco | Ostro | Ostro-Libeccio | Libeccio | Poniente | maestro | Maestro Tramontana |

See also

- Anemoi

- Compass rose

- Wind rose (meteorology) , graphic for the distribution of wind directions and wind speeds in one place

Web links

- 12 winches on a world map by the German cartographer Sebastian Münster (1488–1552).

- Direction of the nautical winds on a map from the "Atlas novus" (approx. 1680) by the Dutch cartographer Jan Jansson (1558–1664)

- Communications from Justus Perthes' Geographical Institution , A. Petermann, Verlag Perthes, Gotha 1861

- Handbook of ancient geography , Albert Forbiger, Mayer & Wigand Verlag, Leipzig (1842)

- Hellas , Friedrich Kruse, Verlag Voss, Leipzig (1825)

- Introduction to Physics , G. Karsten (Ed.), Verlag Voss, Leipzig (1899)

- Navigare necesse est - History of Navigation , G. Wolfschmidt (Ed.), Books on Demand, Norderstedt 2008

- History of seafaring , Robert Bohn, Verlag C. H. Beck, Munich 2011

- The Ancient Studies , SFW Hoffmann, Verlag JC Hinrichs, Leipzig (1835)

Individual evidence

- ^ Friedrich August Ukert - Geography of the Greeks and Romans from the earliest times to Ptolemy , p. 177 ( books.google.de ).

- ^ Vitruvius Pollio: Architecture. Volume 1, translated by August Rode, p. 50 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Cecil Brown: Where Do Cardinal Directions Terms Come From? In: Anthropological Linguistics. 1983.

- ↑ Genesis 13:14, Gen. 28:14; Deuteronomy 3:27

- ↑ Aperçus historiques sur la rose des vents

- ^ Emil G. Hirsch, Immanuel Benzinger, Jewish Encyclopedia, Winds , 1906.

- ↑ Jeremiah 49:36, Ezekiel , Daniel 8.8, 37: 9, Zacharias 2: 6

- ↑ Genesis (41: 6), Ezekiel 19:12

- ↑ Ezekiel 5:10

- ↑ a b Aperçus historiques sur la rose des vents. P. 11 ( books.google.com ).

- ↑ Gerhard Köbler: Ancient Greek Dictionary of Origin (PDF).

- ↑ Heraclitus, fragment 120: ἠοῦς καὶ ἑσπέρας τέρματα ἡ ἄρκτος καί ἀντίον τῆς ἄρκτου οὖρος αἰθρίου Διός (translated from the quote in Strabo , the big bear and the climax of the great bear are "endpoints" from the aurora and the high points of the bears) the Zeus children. ")

- ↑ Iliad (18: 489), Odyssey (5: 275)

- ↑ Alexander von Humboldt , Kosmos, Volume 3, p. 160 ( gallica.bnf.fr ).

- ↑ At least this is what Thrasyalkes of Thassos claims, as Strabo reports in his work Geographica ( I.21 ). See also Gosselin (1805: xcviii ). This should come as no surprise, as Brown found in his 1983 survey that winds tend to be far more commonly associated with north-south directions than with west-east directions (the latter being determined mainly by sun-related terms).

- ↑ Based on the cosmographic explanations of Isidore of Seville .

- ^ FEJ Valpy: The etymology of the words of the Greek language. P. 26 ( books.google.de ).

- ^ Aulus Gellius , Noctes Atticae: Attic nights. (Complete German translation), p. 138 ( books.google.de ), Chapter 22, pp. 146–147 (English translation books.google.de ).

- ^ FEJ Valpy: The etymology of the words of the Greek language. P. 114 ( books.google.com ).

- ^ FEJ Valpy: The etymology of the words of the Greek language. P. 52 ( books.google.de ).

- ^ Falconer 1811, The Quarterly Review, Volume 5, p. 294 ( books.google.com ).

- ↑ . See Homer: "βορέης καὶ Ζέφυρος, τώ τε Θρῄκηθεν ἄητον / ἐλθόντ 'ἐξαπίνης · ἄμυδις δέ τε κῦμα κελαινὸ." (Iliad ix 5f) - [ https://www.gottwein.de/Grie/hom/il09.php “North and roaring west, both of which waft from Thrace, / Coming in swift fury; and immediately now dark waves ”(Voss).

- ↑ . See Homer: "πληθύν, ὡς ὁπότε νέφεα Ζέφυρος στυφελίξῃ / ἀργεστᾶο Νότοιο βαθείῃ λαίλαπι τύπτων ·" (Iliad xi 305f.) - [ https://www.gottwein.de/Grie/hom/il11.php "among the people : as the west throws apart the clouds / From the pale shivering south, displacing them with a heavy storm; ”(Voss).

-

↑ a b c Reference error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text given for individual records with the name strabo . - ^ Geographie de Strabo

- ↑ D'Avezac (1874: p. 12 )

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Natural History, Chapter 46

- ↑ Hesiod does not mention Argestes as the fourth wind, see Theogony 379 and 870 .

- ↑ Hippocrates, "De aere, aquis et locis" (English translation)

- ^ Aristotle, Meteorologica, Chapter 6

- ^ FEJ Valpy: The etymology of the words of the Greek language. P. 45 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ Strabon, Geographica, Book 1.2.21, p. 43

- ^ FEJ Valpy: The etymology of the words of the Greek language. P. 67 ( books.google.de ).

- ^ FEJ Valpy: The etymology of the words of the Greek language. P. 97 ( books.google.de )

- ^ FEJ Valpy: The etymology of the words of the Greek language. P. 61 ( books.google.de ).

- ^ FEJ Valpy: The etymology of the words of the Greek language. P. 104 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ See Thompson (1918)

- ^ Thompson (1918: p. 53 books.google.com ).

- ↑ D'Avezac (1874: p. 18)

- ↑ Malte-Brun: Universal Geography. P. 135 ( books.google.de ).

- ↑ This distinction is suggested in the translation by JG Wood (1894): p. 17 Textarchiv - Internet Archive , p. 83 Textarchiv - Internet Archive . In Hort's translation (1916), on the other hand, the view is taken that it is used synonymously (e.g. BS 416 books.google.com ).

- ↑ Ventorum Situs - Internet Archive , translated into English by ES Forster: The Works of Aristotle. Volume 6, 1913.

- ↑ See translator ES Forster's note on p. 252 in The Works of Aristotle - Internet Archive Band. 6 (1913). Forster translates the text as a compound word Euronotos .

- ↑ Geographi graeci minores p. 178 and Geographica antiqua, p. 472

- ↑ Agathemeros provides a representation of their relative position in his work Geographia .

- ↑ This list is based primarily on Agathemeros: Geographica antiqua , p. 473 or Geographi graeci minores ( p. 179–180 )

- ^ D'Avezac, Aperçus historiques sur la rose des vents (1874: p. 19 )

- ↑ Johannes von Damascus, Orthodoxou Pisteos / De Fide Orthodoxa, Lib. II, chap. 8, pp. 899-902

- ^ Translation by E. S. Forster, 1914, Works, Volume 3, pp. 159 ff. Archive.org

- ↑ De Mundo chap. 4, p. 632

- ↑ Vitruvius (Book 1, Chapter 4, p. 27 )

- ^ Bunbury (1879: 588 )

- ↑ More on this in the article Graecization .

- ^ Virgil, Georgica, Lib. 3: Z. 273-279

- ↑ Wood (1894: p. 88 Textarchiv - Internet Archive ) regards the meridian implied by Seneca as Euronotos - Thrascias .

- ↑ Pliny the Elder Ä .: The natural history - Internet Archive Second book. 161 44.

- ↑ See Pliny book. 2, Chapter 46 versus Pliny Book 18, Chapter 7.7

- ↑ Pliny: The natural history. archive.org Second book. 161 46.

- ↑ Pliny: The natural history. Textarchiv - Internet Archive Second Book. 86.

- ↑ Aulus Gellius , Noctes Atticae ( Attische Nights (complete German translation), pp. 138-139 ), Chapter 22, (English translation) p.146

- ↑ Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights, Lib. II, chap. 22, p.148

- ↑ As with Lais (1894: p. X )

- ↑ As with Wood (1894: p. 89 )

- ↑ Isidore of Seville, Etymologiae Chapter XI

- ↑ Plin. Nat. 18.77

- ↑ Walde, Reichardt, Comparative Dictionary of Indo-European Languages, p. 34

- ↑ Ingmar Knacke, Studies on the Battle of Cannae (216 BC) - p. 43 , the like less comprehensive

- ↑ Wood (1894: p. 90 )

- ↑ a b c Ward (1894: p. 68 )

- ↑ Walde, Reichardt, Comparative Dictionary of Indo-European Languages, p. 305

- ↑ Aulus Gellius , Noctes Atticae ( Attische Nights (complete German translation), pp. 138-139 ), Chapter 22, (English translation) p.146

- ^ Virgil, Georgica, Lib. 3: Z. 278 . Oddly enough, Virgil mentions that the rain is cold, which is not true - oyster was hot and humid. But he uses the same phrase as Boreas and Caurus , which were actually cold and damp winds.

- ↑ Origin of the root ‹Afri› in Africa or Africus

- ↑ The natural history of Cajus Plinius Secundus. archive.org Volume 1, 248.

- ↑ Lorenz Diefenbach, The old people of Europe with their clans and neighbors, p. 299

- ↑ Vitruvius 1,6,10 ( Latin , English )

- ↑ a b c In the Latin original edition of Vitruvius (Leipzig 1892, p. 24 ) Boreas occupies the position ONO, Eurocircias is on OSO and Leuconotus on S to O. In the English translation by Morgan (1914) Boreas is mistakenly on ONO Caecias replaced. In Gosselin's list (1805: S. cvii ), Caecias erroneously appears in the position OSO (instead of Eurocircias ) and Euronotus in SE (in place of Leuconotos ). Neither Caecias nor Euronotos appear in the original Latin edition.

- ↑ Although often transcribed into English as euroclydon (KJV, from the Greek εὐροκλύδων), it is Euroaquilo from the Latin Vulgate . If the biblical name, Euro-Aquilo , also suggests an east-northeast wind, its direction would have to be assumed to be east-northeast, relative to Vitruvius's Italy. The name Circias can be a reference to a hurricane , or at least a very stormy wind. In the southeastern Mediterranean, a reference to his power (as Paul in Acts reported Acts 27:14 ). It could be the same violent wind that ( Mark 4, 37) Luke (8, 23) is said to have been calmed by Jesus .

- ↑ Georgius Agricola (1556: Bk. 3, Lat: p.37 ; Eng: p.58 )

- ↑ Apparently not Vitruvius's 24-point compass, but a conventional twelve-point compass in which 'day and night' are halved. This rare and eccentric card deserves a lot of discussion. See d'Avezac ( 1888 ) and Uhden (1936).

- ↑ Einhard, "Vita Karoli Magni", (Latin: p. 22 ; German: p. 61 )

- ↑ Werner Betz : Charlemagne and the Lingua Theodisca. In: Wolfgang Braunfels et al. (Ed.): Karl der Große. Life's work and afterlife. Volume 2: The Spiritual Life. Schwann Düsseldorf 1965, pp. 300–306, here: p. 304.

- ^ Théodore Gutmans: Une terminologie occidentale unifiée dès le Moyen Age: Les quatre points cardinaux. In: La Linguistique. Volume 6, Issue 1, 1970, pp. 147-151.

- ↑ Lettinck (1999: p.173 )

- ↑ Taylor (1937: p. 5)

- ↑ P. d'Ailly, Imago Mundi, (1410: p. 60)

- ^ World map by Heinrich von Meinz

- ↑ Uhden (1936: p. 13).

- ↑ Portolan map by Gabriel de Vallseca (1447)

-

↑ The British Library makes manuscript pages from Matthäus Paris accessible online: On one page a normal "twelve-point compass rose" is shown, which Matthäus copied from Elias von Dereham . At the top left are the notes that reflect his preliminary list of the new 'classic' names for 16 winches. Another page shows a "sixteen-point wind rose" in which he has given his classically sounding names at various points on the compass. See Matthew Paris: Twelve Point Compass Rose , at the British Library and Matthew Paris: Sixteen Point Compass Rose , from the British Library.

A summary of the efforts of Matthew Paris is provided by Taylor (1937). - ↑ Taylor (1937: p. 26)

- ↑ The compass rose on St. Peter's Square in Rome (English)