Noctes Atticae

The Noctes Atticae ("Attic Nights") were written in the second half of the 2nd century by the Roman writer and judge Aulus Gellius .

Emergence

The title of the work is explained by the fact that Gellius began to write during the long winter nights he spent in Attica ( quoniam longinquis per hiemem noctibus in agro […] terrae Atticae commentationes hasce ludere ac facere exorsi sumus, idcirco eas inscripsimus noctium esse Atticarum ). The dating can almost only be based on information inherent in the text of Gellius. It can be seen from these that he conceived the work in connection with a trip to Athens during the years 147 and 148, worked on it further in Rome, and that it was not published until around 180.

The work is a reflection of the literary atmosphere of the 2nd century in the closely linked “ cultural areas ” of Greece and Rome.

Content

In colorful succession, Gellius worked out his notes on all kinds of interesting, piquant or curious things into small essays. While the individual chapters are usually clearly structured and confidently formulated, there is no systematic overall order. The book reflects the education and knowledge of the later imperial era. In his texts Gellius deals with a wide variety of problems. The most important topics are:

- Grammatical and philological treatises on lexical and etymological topics: This group of topics occupies a special place. Not only questions of grammar are discussed - for example whether Marcus Terentius Varro and other important Roman writers form the genitive and dative correctly (Book IV, 16) - but also the correct pronunciation and accentuation of words (Book IV, 7).

- Interpretation of Greek and Latin literature : This is how Gellius compares the Latin comedy The Collar of Caecilius Statius with his Greek model of Menander on the basis of a detailed comparison of Latin and Greek text passages.

- Literary history and literary criticism

- Philosophical and moral-philosophical questions: It is important for the author to prove his knowledge in this area. In a short text on one aspect of the teaching of Epicurus , he places the philosophers Hierocles, Antisthenes , Critolaus, Plato and his teacher in Athens Taurus (Book IX, 5).

- Greek and Roman history : There are anecdotal sketches, such as “a biting answer that the Punic Hannibal jokingly gave to King Antiochus” (Book V, 5). Republican Roman history is also honored through extensive quoting of Roman historiography (Book IX, 13).

- Mirabilia : Cyclops , dog-headed people, hermaphrodites (Book IX, 4), but also the story of the friendship between a boy and a dolphin who carries him through the water on his back and dies of grief when he dies (Book VI, 8 ).

- Legal problems

- Natural sciences ( astronomy , mathematics ) and medicine : Gellius reports on the relief of pain and even the healing of snake bites by playing the flute (Book IV, 13).

swell

Gellius uses an extraordinary number of sources and mentions most of them by name. The reading fruits of around 275 authors can be found in his work. He excerpts roughly the same number of Greek and Roman authors and often includes the untranslated original Greek text in his work.

His quotations start with the early Greek authors Homer and Hesiod and extend to his contemporaries. Many writers are only consulted a few times, but for authors who were important for the intellectual world of the time, such as Homer, Quintus Ennius , Plato , Marcus Porcius Cato the Elder , Marcus Terentius Varro , Marcus Tullius Cicero , and Virgil , the number of citations is in the middle double-digit range .

Gellius shows a particular fondness for the Roman literature of the republican and also the Augustan period, especially old speakers (especially Cato), historians ( Quintus Claudius Quadrigarius ), authors of philosophical writings (Cicero) and poets (especially valued and often called Virgil) ; It is noticeable that Ovid and Titus Livius are not mentioned at all, Horace only in a single article.

But not only reading fruits are a source of his work, but also: "Worth knowing that I have heard" ( quid memoratu dignum audieram ). Here contemporaries are necessarily in the foreground. Gellius likes to organize the knowledge transfer in an entertaining dialogue and gives the names of the participants. For example, he dedicates several articles to his teacher in Rome, Antonius Iulianus , who - like some other authors - can only be grasped through Gellius, as well as the Platonist Lukios Kalbenos Tauros , with whom he studied in Athens. The philosopher Favorinus , whom he mentions 27 times in his work and gives his voice to a wide variety of topics, is of particular importance to him .

intention

Gellius himself formulates his intention. The preserved part of the praefatio begins in the translation by Georg Fritz Weiß :

“Other more attractive scriptures will be found; but the purpose that I pursued in writing this work was none other than that my children should find appropriate recreational reading immediately in the free periods, when they can rest mentally from their work and indulge in their own amusements. "

But he doesn't just address his children. As further explained in the praefatio , he wants to entertain “people who are occupied with other life obligations ” ( delectatio ), but also provide them with the necessary basic knowledge so that they can competently participate in a conversation. A complete collection of the topics or even only a systematic classification is not aimed for.

It can be seen that he limited himself to historical anecdotes and people from the time of the kings and the republic (753–31 BC); In contrast, there are hardly any episodes from the imperial era in his compilation . The reason for this was probably that Gellius wanted to show his children what behavior, what values and what norms Rome had become what it represented in the middle of the 2nd century. That is why he included in his collection many texts that had been written 400 years earlier, reproducing some literally and others in his own words.

Shape and style

The extensive work is divided into 20 books, which are introduced by a praefatio and a table of contents. The books are in turn divided into 398 chapters of very different formats and contents. Before each chapter there is a short, summarizing table of contents. Book 8 has been lost except for these table of contents.

Gellius often uses not only Latin , but also Greek quotations , so that the typical bilingualism of this era is conveyed. Some of the chapters follow the tradition of imparting knowledge in the Roman encyclopedia . But he also inserts controversial grammarians or philosophers and exact quotations into his texts in order to achieve liveliness. Table discussions and street chats in verbatim speech, historical anecdotes loosen up the text.

There is no specific order of the materials. Gellius excerpts the books as they come into his hands without any plan. Instructive texts, miracle stories and conversations with a philosophical content are in a colorful sequence

The refinement and enrichment of his language was very important to Gellius. He used numerous atticisms in the Greek as well as archaisms in the Latin parts of his work, reviving expressions and grammar constructions from older pre-classical poems. In addition, however, there are also new word formations , some of which arise through the reorganization of existing words, and some through the use of Greek words. Overall, it is a rich language, also adorned with the accumulation of synonyms .

Significance and aftermath

Gellius is one of the writers who convey a picture of their time through a collection of various excerpts . With this he fits into the "miscellular literature" and is therefore also considered a representative of colored writing . Gellius takes his excerpts from the most varied areas of knowledge, grammar, dialectics , philosophy, arithmetic , law , history, etc., but also mixes all kinds of incidents and even miracle stories. The Noctes Atticae are therefore of central importance for research into the reception of the second century AD. They convey a vivid picture of the reading and educational culture. The starting point is not only the content, but also the narrative cladding of the work, which reflects the intellectual and cultural interests of the imperial educated middle class.

The work of Gellius itself was received many times. Some authors edit his texts without giving his name, such as Nonius Marcellus , who uses it about 100 times. Knowledge of the Noctes Atticae could also be demonstrated in Lactantius , also in Apuleius , Macrobius and several others. The church father Augustine of Hippo quotes an anecdotal text from the Noctes Atticae (Book XIX, 1) in his work De civitate Dei (IX, 4) when dealing with the emotional affects and serenity of the Stoics . Augustine praises Gellius as a vir elegantissimi eloquii .

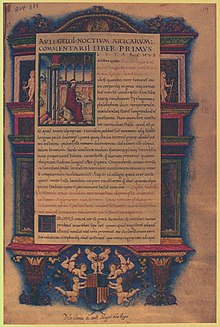

The tradition of the work through the centuries is complex. The original condition, consisting of the praefatio and 20 books, can only be proven by quotations from ancient authors. The work was soon divided into two volumes: praefatio and books I to VII and books IX to XX. Book VIII is already missing here and has been largely lost. Parts of this text design are covered by the Codex Vat. Pal. Lat. 24 (according to a controversial dating from the 5th to the 7th century). In the sphere of influence of the Carolingian cultural reform there are further text divisions. Manuscripts that contain books I to VII or IX to XX in full are only available from the later Middle Ages, mainly the 13th century, but then in several European libraries. The first printed edition appeared in Rome in 1469. In 1883 Martin Hertz created a complete edition with critical commentary. The only complete translation into German by Georg Fritz Weiß (1875) is also richly commented on.

The Noctes Atticae were highly valued in the high Middle Ages and early modern times . At this time Gellius corresponded with his teaching of general education and his moral treatises the thirst for knowledge of the educated class. One of his readers was the English theologian John of Salisbury . His successor was soon the humanist and color writer Angelo Poliziano . Hartmann Schedel mentioned him in his world chronicle (1493). After all, the essay writer Michel de Montaigne was also a reader and imitator of his work and deals with Gellius' thoughts. Montaigne also took the typical three-step consisting of preface, narrative and moral and spread it. On December 1, 1641, the Sunday Collegium Gellianum was founded in Leipzig . It took place after the services and dealt with philological questions and problems.

The Noctes Atticae are still an important source of historical and linguistic details as well as numerous fragments from lost works by ancient authors. They are also extremely valuable for understanding Roman and Greek society in the time of Emperor Marcus Aurelius , when educated people like Gellius liked to turn to the glorious past in a 'classicist' tendency.

expenditure

- Original Latin text

- Martin Hertz (Ed.): A. Gellii Noctium Atticarum libri XX . 2 volumes., Berlin 1885.

- Carl Hosius (Ed.): A. Gellii Noctium Atticarum libri XX ( Bibliotheca Teubneriana ). 2 vols, Leipzig 1903 (online: Volume 1 , Volume 2 )

- Peter K. Marshall (Ed.): A. Gelli Noctes Atticae ( Oxford Classical Texts ). 2 volumes, Oxford 1968 (corrected edition: Oxford 1990).

- Leofranc Holford-Strevens (Ed.): Avli Gelli Noctes Atticae ( Oxford Classical Texts ). 2 volumes, Oxford 2019 (authoritative text-critical edition).

- German translations

-

Georg Fritz Weiß (ed. And translator): The Attic nights . 2 volumes, Leipzig 1875–1876 ( digitized ; only complete German translation).

- Reprint: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1981.

- Heinz Berthold (ed.): Attic nights. From a reading book from the time of Emperor Marc Aurel. Insel Verlag, Leipzig 1987 (selection translation).

- Hartmut Froesch (ed. And translator): Noctes Atticae / Attic nights . Latin-German. Reclam, Stuttgart / Ditzingen 2018 (selection translation).

- English translation

- John C. Rolfe (translator): Attic Nights . Latin-English ( Loeb Classical Library ). 3 volumes, Cambridge (MA) 1927.

- Adaptations for school use

- Noctes atticae. Accesserunt eruditissimi viri Petri Mosellani in easdem perdoctae adnotationes. Martin Gymnich, Cologne 1549 ( new edition of the “Attic Nights” edited by Petrus Mosellanus ).

- Josef Feix (Ed.): Noctes Atticae . Schöningh Verlag in the Schulbuchverlag Westermann, Paderborn 1978, ISBN 3-14-010714-5 .

- Michael Dronia (Ed.): Transfer 1. Stories from ancient Rome. From Gellius, Noctes Atticae. Excerpts with learning materials. Buchner Verlag, Bamberg 2003, ISBN 3-7661-5161-4 .

literature

- Carl Hosius : History of Roman Literature. The time from Hadrian 117 to Constantine 324 (= manual of classical antiquity in a systematic representation . Volume 8, part 3). CH Beck, Munich 1922.

- Peter Steinmetz : Studies on Roman literature of the second century after the birth of Christ . Franz Steiner, Wiesbaden 1982.

- Reinhart Herzog , Peter Lebrecht Schmidt : Handbook of the Latin literature of antiquity. Volume 4: The literature of upheaval. From Roman to Christian literature. 117 to 284 AD. CH Beck, Munich 1989.

- Leofranc Holford-Strevens : The Worlds of Aulus Gellius . Oxford University Press, Oxford 2004.

- Dennis Pausch : biography and culture of education . De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2004.

- Jens-Olaf Lindermann: Comment . In: Aulus Gellius: Noctes Atticae , book 9. Weißensee Verlag, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-89998-097-4 .

- Julia Fischell: The writer Aulus Gellius and the themes of his “Noctes Atticae”. Dissertation University of Hamburg, 2008 ( online ; not evaluated here).

- Wytse H. Keulen : Gellius the Satirist. Roman Cultural Authority in "Attic nights" . Brill, Leiden 2009.

- Christine Heusch: The power of memoria. The “Noctes Atticae” by Aulus Gellius in the light of the culture of remembrance of the 2nd century AD. De Gruyter, Berlin 2011.

- Joseph A. Howley: Aulus Gellius and Roman Reading Culture. Text, Presence, and Imperial Knowledge in the Noctes Atticae . Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 2018.

Web links

- Text of Marshall's edition at PHI Latin Texts

- Latin text with English translation of the preface and books 1–13 by John C. Rolfe (1927) at LacusCurtius

- Latin text of the Noctes Atticae at The Latin Library (incomplete)

- Nuits attiques (French translation, 1927)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Noctes Atticae , praefatio , 4.

- ↑ Christine Heusch: Die Macht der memoria , p. 51, especially note 8.

- ↑ Christine Heusch: Die Macht der memoria , p. 191.

- ↑ Christine Heusch: Die Macht der memoria , p. 52.

- ↑ Peter Steinmetz: Studies on Roman literature of the second century after the birth of Christ , p. 278.

- ↑ Peter Steinmetz: Studies on Roman literature of the second century after the birth of Christ , p. 288.

- ^ Martin Hertz: A. Gellii Noctium Atticarum libri XX , Index Auctorum .

- ↑ Peter Steinmetz: Studies on Roman literature of the second century after the birth of Christ , p. 289.

- ↑ Noctes Atticae , praefatio , 2.

- ↑ Aulus Gellius: Noctes Atticae , ed. by Jens-Olaf Lindermann. Book 9: Commentary , p. 65.

- ↑ Reinhart Herzog: Aulus Gellius . In: The literature of upheaval , p. 69.

- ↑ Reinhart Herzog: Aulius Gellius . In: The literature of upheaval , p. 70.

- ↑ Dennis Pausch: Biographie und Bildungskultur , pp. 154, 159 f.

- ↑ Christine Heusch: Die Macht der memoria , p. 51 f.

- ↑ a b Reinhart Herzog: Aulus Gellius . In: The literature of upheaval , p. 71.

- ↑ a b c Carl Hosius et al .: The time from Hadrian 117 to Constantin 324 , p. 177.

- ↑ Christine Heusch: Die Macht der memoria , p. 226 ff.

- ↑ Leofranc Holford-Strevens: The worlds of Aulus Gellius , p. 49 ff.

- ↑ Leofranc Holford-Strevens: The worlds of Aulus Gellius , p. 53 ff.

- ↑ Leofranc Holford-Strevens: The worlds of Aulus Gellius , p. 59.

- ↑ Noni Marcelli De compendosa doctrina , edition Wallace M. Lindsay, Hildesheim 1964 Index Auctorum.

- ↑ RM Ogilvie: The library of Lactantius , Oxford 1978, p. 46 f.

- ↑ Carl Hosius. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume 4, Stuttgart 1893ff., Sp. 992-998.

- ↑ Reinhart Herzog: Aulus Gellius . In: The literature of upheaval , p. 74.

- ^ John C. Rolfe: The Attic nights of Aulus Gellius , Introduction, pp. XVIII-XXII.

- ↑ Christine Heusch: Die Macht der memoria , p. 398.

- ↑ Christine Heusch: Die Macht der memoria , p. 399.

- ↑ Christine Heusch: Die Macht der memoria , p. 400.

- ↑ Maximilian Görmar: The Collegium Gellianum in Leipzig (1641–1679) - A contribution to Gellius reception in the 17th century . In: International Journal of the Classical Tradition . tape 25 , no. 2 , 2018, ISSN 1874-6292 , p. 127-157 , doi : 10.1007 / s12138-016-0427-1 .

- ↑ Christine Heusch: Die Macht der memoria , p. 400 f.