Antisthenes

Antisthenes ( ancient Greek Ἀντισθένης Antisthénēs ; * around 445 BC; † around 365 BC) was a Greek philosopher of antiquity . He lived in Athens and was the founder and one of the main exponents of the teaching of Cynicism .

Antisthenes was probably one of the most famous philosophers of Athens in his time. He was a student of Socrates , 20 years his senior , a contemporary of Plato and a teacher of the Cynic Diogenes of Sinope . In the history of philosophy, Antisthenes is often counted among the so-called little Socratics .

From the writings of Antisthenes nothing has survived apart from two short exercise speeches. What is known today about his life and teaching has been gathered from reports by other ancient authors. Overall, the tradition is poor. The most important information about Antisthenes comes from his contemporaries Xenophon , Aristotle and the third-century historian of philosophy Diogenes Laertios .

Antisthenes was known to disregard luxury and wealth while advocating needlessness . In the field of logic , Antisthenes dealt with definitions and statements ; on that of epistemology he questioned the existence of Platonic ideas against Plato's theory of ideas. He has also dealt with political issues and interpreted works by the poet Homer .

Life

The lifetime of Antisthenes can be reconstructed comparatively well from the ancient reports and is dated 445 to 365 BC. Estimated.

Antisthenes was the son of an Athenian citizen of the same name and a Thracian woman . He is said to have lived - at least for a while - in Piraeus, 8 km from Athens . Antisthenes died of illness around the age of 80. He was initiated into the Orphic Mysteries and received an award at the Battle of Tanagra .

About the external appearance of Antisthenes, who was nicknamed "pure dog" ( haplokyon ), it is reported that he wore a shabby coat when he met Socrates and that he generally carried nothing but a double-turned coat and carried a stick and hanging bag should have. To describe his character, it is said that he is "an unusual man who wins everyone over through his witty intercourse." In the late antique philosopher Diogenes Laertios one can also read numerous anecdotes from the life of Antisthenes and several pithy sayings ascribed to him. In Xenophon's Symposium , Antisthenes appears on the one hand as a cynical philosopher and needless person, on the other hand as a constantly teasing critic who questions the opinions of other interlocutors, likes to mess with others and occasionally makes fun of them. For example, he names the wife of Socrates as the one "who among all living people, yes, as I wish, among all who have lived in the past and will live in the future, is the most unbearable" and asks a certain Nikeratos , who shows similarities with the ancient rhapsodes , whether he knows a "sillier people in the world than the rhapsodes".

At first Antisthenes was probably a student of the sophist Gorgias von Leontinoi , but later switched to the followers of Socrates , "whose steadfastness and serenity ( apatheia ) he made his own and thus founded the Cynical way of life." Antisthenes had his conversations in an Athenian high school , the Kynosarges . This was assigned to those Athenians for their exercises who, like Antisthenes, had a non-Athenian parent and thus politically did not count as full citizens.

Isocrates wrote two speeches in which he turned against the Socratics and also specifically against the Cynics and Antisthenes. Based on this document, some researchers assume that Antisthenes was the most famous Socratics in the first decades after the death of Socrates, thus also more famous than Plato.

The relationship with Plato was probably not the best. Antisthenes is said to have mocked him for his pompousness, ostentation and arrogance. In a play on words he called him instead of Plato ("with a broad forehead") Sathon ("with a thick member"). Diogenes Laertios makes a connection in three places between Antisthenes and the school of the Stoa , which may have been influenced by the teaching of Antisthenes.

Teaching

Antisthenes is already considered by the ancient historian of philosophy Diogenes Laertios to be the founder of a new direction within philosophy, which was later called cynicism . The cynicism was best known for its ethics, which speak out in favor of needlessness and against luxury and social conventions. The most famous of the few students of Antisthenes was Diogenes von Sinope, other representatives of Cynicism can be found in philosophical historians up to the 4th century.

Fonts

Antisthenes wrote numerous works, Diogenes Laertios gives the titles of 60 to 70 works, which were collected in 10 volumes. Among them were dialogues, tracts, and practice speeches . The catalog and its reception were examined in detail by Andreas Patzer . It is unclear which of the writings mentioned actually existed. Basically, however, the Diogenes catalog of writings is classified as trustworthy and it is assumed that he may have created it based on the library catalogs available to him, but above all based on the resulting collective publications. The philosophical-historical and biographical writings in question, which also contained book lists, were written during the Hellenistic period , especially in the cities of Alexandria and Pergamon . Possible authors who treated Antisthenes with certainty were Satyros of Kallatis , Hermipp , Sotion of Alexandria (* around 200 BC; † 170 BC), Panaitios and Herodicos of Babylon . Patzer concludes from the arrangement of the titles that there must have been a complete edition of Antisthenes 'writings in antiquity, which Diogenes Laertios' report of a ten-volume work also suggests.

Some researchers ascribe to Antisthenes the two surviving, extremely short practice speeches Aias and Odysseus , which are named after the heroes Ajax the Great and Odysseus . They were handed down in manuscripts by speakers . In them Ajax and Odysseus claim the weapons of the deceased Achilles for themselves.

Antisthenes also wrote interpretations of Homer's poems. Porphyrios later gave a lecture on these interpretations , of which so-called Homer scholias have survived .

ethics

"I'd rather go crazy than enjoy."

“Even better than lust is madness. You should never lift a finger for the sake of pleasure. "

"Lust is only a good if it does not result in remorse."

"One can strive for the pleasure that lies behind the exertion, but not that which lies before it."

"When asked about the greatest happiness for people, he said:" To die with a cheerful heart! ""

"... whoever wants to become immortal must lead a dutiful and fair life."

"It is royal to do good, to experience bad."

“The wise man is hard to bear; for just as incomprehension is easy and bearable, so insight is something firm, intransigent and has an unshakable weight. "

"You shouldn't be grateful to anyone who praises you."

“You don't have to put an end to contradiction through contradiction, but through instruction; because even a madman cannot be cured by racing against him again. "

"The wise do not conduct politics according to the existing laws, but according to the law of morality."

"When the rabbits in the People's Council demanded equal rights for all, the lions said:" Your speeches, you rabbits, are missing the claws and teeth we have. "

" (To a priest who collected gifts for his deity :) I do not receive the mother of gods, that is the gods' business."

"According to the prevailing belief there are many gods, but only one by nature."

“One does not see God with eyes and he is not like anyone; therefore you cannot recognize him from a picture. "

"The beginning of education is the study of words ( onomaton )."

"The" it was "is completely sufficient in itself."

"Logic is sterile."

- Luxury and needlessness

Antisthenes was directed against a luxurious life: "I wish my enemies that their children live in luxury!" He is said to have asked the husband of a heavily dressed woman to show him a horse and weapons, since luxurious dressing should only come after adequate defense . In contrast to luxury, Antisthenes praises self-sufficiency in the sense of needlessness.

When the question arises in Xenophon's symposium , what Antisthenes imagines most, the latter answers that he is wealthy. When it turned out that he had neither a dime in cash nor land, he explained that wealth is "not in our homes, but in our souls". Immediately after this quote there is a longer passage in which Antisthenes explains his position - to which the "art of needing nothing" is ascribed shortly afterwards - in relation to luxury and lack of need. So there are very rich who still want to amass more money and, like some tyrants, do not even shrink from murder and enslavement of entire cities. He himself had little, but enough to eat, drink, clothes and a house. He doesn't like to get up and be content with people with whom no one else wants to have anything to do with. He enjoys what he has and would not lose much if it should. Every now and then he affords himself a little something, but leads a less demanding life and needs little money. His wealth consists of treasures in his soul which, like Socrates, he likes to share with others, and in the ample free time that he likes to spend with Socrates.

- Virtue

The following quote about the ethics of Antisthenes focuses on the concept of virtue ( arete ):

“His philosophy was this: virtue, he proved, can be taught. Real nobility is nobility of virtue, virtue alone is sufficient ( self-sufficient ) for happiness ( eudaimonia ) and additionally only requires the strength of a Socrates. Virtue is a matter of action and does not require many words or knowledge. The wise man has enough in himself, for he has all the other goods. Gloriousness is a good thing, as is work. In politics the wise let himself be guided not by the laws of the state, but by that of virtue. "

Antisthenes, whose social status is not known, calls work ( ponos ) a good here. In another passage Diogenes Laertios writes: "That strenuous work is a good thing, he referred to the great Heracles and Cyrus ."

Epistemology

According to Johannes Tzetzes , Antisthenes is said not to have recognized the reality of ideas taught by Plato. According to Antisthenes, these ideas are rather “mere thoughts” ( psilai ennoiai ). An anecdote handed down by Simplikios hits the same note , according to which Antisthenes is said to have said to Plato: “I see a horse, but I see no equestrianism”, to which Plato is said to have replied: “You only have the eye with which one can look Horse sees, but you have not yet acquired the eye with which one sees equestrianism. ”By this, Antisthenes could have meant that genera and species are not something real, existent, but are only based on our ideas.

logic

- definition

Antisthenes is said to have been the first to define ( horisato ) what a statement ( logos ) is: “The statement shows what something was or is.” He can therefore be regarded as one of the forerunners of ancient logic, its first extensive The work of Aristotle. He in turn reports that, according to Antisthenes, definitions should have been impossible:

“So there is a certain justification for the doubt raised by the followers of Antisthenes and those uneducated in this way, namely that it is not possible to define what something is, since the definition takes place through a long series of words, but one can only determine and teach how something is made; silver, for example, cannot be said to be what it is, only that it is like tin. According to this, definition and concept are possible for some beings, for example for the composite, whether these be sensually perceptible or only conceivable; not possible, on the other hand, of those from which they consist as their first constituent parts, in so far as the defining concept says something about something, and one must take the place of matter, the other that of form. "

- Impossibility of objection

Diogenes Laertios mentions a lecture by Antisthenes, the subject of which is said to have been the unspecified "impossibility of contradicting one another". In another passage he ascribes a “principle” to Antisthenes who “seeks to prove the impossibility of contradiction” and refers to the dialogue Euthydemos of Plato, in which this view (which Protagoras also represented) is discussed. Aristotle also takes up this point and calls Antisthenes' view "foolish". Because he claimed:

"One should not say anything about any object other than one's own concept ( logos ):" Only one thing about one. "From this it emerged that it is impossible to make contradicting and almost impossible statements."

Aristotle also reports at another point: "It is not possible to contradict, as Antisthenes says."

politics

Antisthenes seems to have criticized ancient democracy . For example, he advised the Athenians to declare donkeys to be horses by popular resolution, just as they turned unskilled people into commanders by simply raising their hands, and responded to the fact that the crowd praised him: "What did I do wrong?"

The concept of cosmopolitan ( cosmopolites ) appears for the first time in his student Diogenes von Sinope , but Antisthenes already provides an example of Greeks next to one of non-Greeks - to show that strenuous work is something good. A comparison that should have been rather unusual at the time; other contemporary authors referred to all non-Greeks together with the derogatory term barbarians.

theology

In the field of theology, too, isolated fragments of the views of Antisthenes have been preserved, from which, however, by far no overall picture of Antisthenes' theology can be derived.

Lore

Since the writings of Antisthenes - except for the two short speeches - have been lost, almost everything we know today about his life and teaching is taken from texts by other ancient authors. Sometimes they cite original text passages of Antisthenes ( fragments ), sometimes they tell about his life or his teachings or Antisthenes appears as a figure in literary texts. The doxographer Diogenes Laertios reports most extensively, but his work on the life and teachings of famous philosophers only dates from the 3rd century. Another important source is the more literary than philosophical dialogue symposium of Antisthenes' contemporary Xenophon, in which Antisthenes appears alongside Socrates as one of the most active interlocutors. He also appears briefly in Xenophon's Memorabilia .

Compared to Plato and Xenophon, whose writings have been completely preserved, the tradition is extremely poor; Compared to other disciples of Socrates, however, one is well informed about the doctrine of Antisthenes.

The philosophical views of Antisthenes are difficult to reconstruct from the available sources. What is reported about his teaching is mostly fragmentary or consists only of brief wisdom or anecdotes. At Athenaios (who excerpted a writing from Herodicus of Babylon in the 3rd century ) one can read some of the contents of the writings of Antisthenes. As in other dialogues, numerous authors find an allusion to the logic of Antisthenes in the dialog of Sophist of Plato, although he is not mentioned by name. The name of Antisthenes appears only once in Plato, namely in the enumeration of the persons present at the death of Socrates. In Aristotle and his commentators, logical and epistemological views of Antisthenes are reported in some places (see above). In Epictetus , Antisthenes is mentioned four times. In the work of Cicero , who ascribes to him the propagation of a simple way of life, the name of Antisthenes appears four times. Some researchers attribute the template that Dion Chrysostom said he used for his 13th speech to Antisthenes. Little information is available as to the circumstances of Antisthenes' life; almost all of them come from Diogenes Laertios.

reception

The modern reception of Antisthenes consists in the philological collection of ancient and medieval text passages in which Antisthenes is reported, in philosophical-historical presentations of the main points of his philosophy, in monographs that deal exclusively with Antisthenes and in works on special topics of the teachings of Antisthenes.

In the treatment of Cynicism in general, the question was asked to what extent it had an effect on the Cynics and other ancient philosophers who followed it, and whether it can actually be called the founder of the Cynic school.

The pictures that various authors have drawn of the life and teaching of Antisthenes are very different. If one disregards the tradition of the ancient Cynics which he founded, the philosophy of Antisthenes has had little after-effects in the history of philosophy, for example in comparison with the philosophy of his contemporary Plato; rather one can speak of controversies about what the authentic views of Antisthenes actually were. One of the reasons why Antisthenes was not well received is the poor tradition - compared to Plato, for example - but also the fact that the history of philosophy has counted him among the so-called "little Socratics" who, in terms of their aftermath, overshadowed Plato's work stood. Antisthenes also has a certain significance for modern Socrates research. It was hoped that the picture obtained from texts by other authors would be supplemented by the representation of Socrates in Antisthenes.

- Writings on Antisthenes and collections of sources

Gottlob Ludwig Richter (1724) and Ludwig Christian Crell (1728) wrote the first monographic treatises, which, however, were still excessively based on Diogenes Laertios' report . In the 19th century, Antisthenes research expanded, but sometimes fell into "uncritical speculation". Antisthenes received the first treatment within the history of philosophy in 1799 from Wilhelm Gottlieb Tennemann . He was followed by other historians of philosophy, such as Friedrich Schleiermacher , Heinrich Ritter (1830), Eduard Zeller (1846) and Friedrich Überweg (1863). It was not until 1821 that the philological preoccupation with Antisthenes began. Johann C. von Orelli (1821) and Ludwig Preller (1838) published the first compilations of the fragments that have come down to Antisthenes, and in 1842 a first, more detailed, but still incomplete complete edition by Wilhelm Winckelmann appeared. This was followed by an unchanged collection from Friedrich Wilhelm August Mullach , and Gildemeister and Bücheler published further fragments in 1872 and 1885. Monographs were also published again at this time ( Ferdinand Deycks 1841, Charles Chappuis 1854, Adolf Müller 1860), although they concentrated on biographical and literary problems. In the 19th century more and more ancient text passages were brought into an often very speculative connection with Antisthenes, in which his name does not appear. Thus, in 1881 and 1882, writings such as Antisthenes and Plato and On the Mention of the Philosophy of Antisthenes in the Platonic writings could arise, although Plato mentions Antisthenes only once in his writings. Some of the Plato passages found at that time are still valid today - as they are very similar to Antisthenes fragments - as allusions to Antisthenes' philosophy. In 1882 Georg Ferdinand Dümmler attempted to reconstruct Antisthenes' philosophy on a large scale, drawing on numerous passages which he brought into a hypothetical connection with Antisthenes . For Karl Joël , Antisthenes is at the center of all of Xenophon's Socratic writings, as well as many of Plato's dialogues. This direction of a speculative-hypothetical reconstruction of the philosophy of Antisthenes followed in the years 1890 to 1915 by other philologists and historians of philosophy.

Other authors presented more critical treatments in their method from 1890 to 1900, including Paul Natorp and Franz Susemihl . Sharp criticism of the exaggerated interpretations of the 19th century was expressed by Heinrich Maier in 1913 and Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff in 1919 . Subsequently, in 1912, 1932, 1950 and 1951, new, careful and old compilations expanding source collections were created. In 1922 Wilhelm Nestle translated some fragments into German. A certain degree of completion was achieved in 1966 with the Decleva Caizzi collection, and in 1990 the collection of Gabriele Giannantoni, which is the most important today, was published. More recent monographs were written by Giuseppe Zuccante in 1916, Farrand Sayre in 1948 and Caizzi in 1964. Overviews can be found in particular in Olof Gigon (1947) and Jean Humbert (1967). Numerous contributions on special topics such as antisthenic logic, rhetoric and the interpretation of Homer have been made since around 1910.

Today's authoritative monographs come from Andreas Patzer (1970), Herbert David Rankin (1986) and Luis E. Navia (2001).

- Positions of the Antisthenes Reception

The philologically dominated chapter on the cynics in Eduard Zeller's The Philosophy of the Greeks in their Historical Development from 1844–1852, which places philosophical teaching in the foreground over living conditions and anecdotes, is considered the beginning of modern research on cynics . By Theodor Gomperz (1902) the juxtaposition comes from Antisthenes as the founder of the Cynic teaching and Diogenes of Sinope as the "father of the practical Cynicism". Like Karl Wilhelm Göttling and Gomperz before him , Donald R. Dudley directs his presentation on the historical figures behind the Cynic doctrine and speaks out against the fact that Antisthenes should have been the first Cynic. He negates a connection between Antisthenes and the later Cynics and sees it as a subsequent construction of the history of philosophy that arose in antiquity. Whether or not Antisthenes was the first Cynic is a controversial question to this day, which Kurt von Fritz in particular also pursued. In general, one sees in Antisthenes rather the philosopher, whose aftermath is based on his writings, in Diogenes von Sinope his person is in the foreground. Marxist authors such as the Russian I. Nachov and Heinz Schulz-Falkenthal focus on the socially critical aspect of the teaching of Antisthenes. They depict Antisthenes as a representative and advocate of the working, lower classes of society.

Like all philosophers, Antisthenes in systematic accounts of the history of philosophy is ascribed a philosophical position that is determined more by the philosophical-historical view of the respective author than by a philologically correct processing, which must fit into the author's interpretation of the history of philosophy. In Hegel, for example, in Antisthenes virtue is:

“... not unconscious virtue, like the immediate one of a citizen of a free people who fulfills his duties towards the fatherland, class and family as the fatherland, class directly demand. The consciousness, having gone out of itself, now needs to become spirit, to grasp all reality and to become conscious or to understand it as its own. Such states, however, which are called innocence or beauty of the soul and the like, are child states, which are now being praised in their place, from which man, because he is reasonable, must step out and from the abolished immediacy must create himself again. "

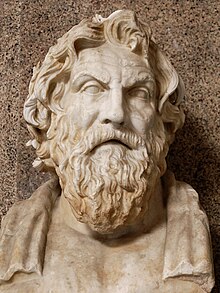

Portraits

There are two known ancient sculptures that could represent Antisthenes. The original of the first is not preserved, but is known from a total of 11 Roman copies. A second-century copy is a herm found in Tivoli in the 1770s with the inscription ANTISTHENES , which is now in the Sala delle Muse of the Vatican Museums. Since 1969 in Ostia Antica the name of the sculptor Phyromachus was discovered on one of the copies , some researchers have ascribed the unknown original, which was made of bronze, to this artist. Phyromachus, however, worked in the 2nd century BC. BC, so much later than Antisthenes, who already in the 4th century BC. BC died.

The second sculpture is a bronze head that was found by divers near Brindisi in 1992 . It is believed to be the portrait of a philosopher, possibly Antisthenes.

Source editions and translations

Editions (partly with translation)

- Gabriele Giannantoni (Ed.): Socratis et Socraticorum Reliquiae , Volume 2, Bibliopolis, Naples 1990, ISBN 88-7088-215-2 , pp. 137-225 (critical edition of the Greek and Latin sources; online )

- Fernanda Decleva Caizzi (Ed.): Antisthenis fragmenta . Istituto Editoriale Cisalpino, Milano 1966 (uncritical edition with commentary)

- Susan H. Prince (Ed.): Antisthenes of Athens: Texts, Translations, and Commentary. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor 2015, ISBN 978-0-472-11934-9

Translations

- Georg Luck (ed.): The wisdom of dogs. Texts of the ancient Cynics in German translation with explanations (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 484). Kröner, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-520-48401-3 , pp. 35-75.

- Wilhelm Nestle : The Socratics . Scientia, Aalen 1968 (reprint of the Jena 1922 edition), pp. 79–98 (translation of 101 fragments; online )

literature

Overview representations

- Klaus Döring : Antisthenes . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy . The philosophy of antiquity , Volume 2/1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, ISBN 3-7965-1036-1 , pp. 268-280

- Marie-Odile Goulet-Cazé, Marie-Christine Hellmann : Antisthène . In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 1, CNRS, Paris 1989, ISBN 2-222-04042-6 , pp. 245-254

- Paul Natorp : Antisthenes 10 . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume I, 2, Stuttgart 1894, Sp. 2538-2545.

- Susan Prince: Socrates, Antisthenes, and the Cynics . In: Sara Ahbel-Rappe, Rachana Kamtekar (Ed.): A Companion to Socrates . Blackwell, Malden 2006, ISBN 1-4051-0863-0 , pp. 75-92

Monographs

- Luis E. Navia: Antisthenes of Athens. Setting the World Aright . Greenwood, Westport 2001, ISBN 0-313-31672-4

- Andreas Patzer: Antisthenes the Socratics. The literary work and philosophy represented in the catalog of the writings . Partial print, Heidelberg 1970 (dissertation)

- Herbert David Rankin: Anthisthenes [sic] Sokratikos . Hakkert, Amsterdam 1986, ISBN 90-256-0896-5

Investigations on partial areas

- Aldo Brancacci: Oikeios logos. La filosofia del linguaggio di Antistene . Bibliopolis, Naples 1990, ISBN 88-7088-229-2

- Aldo Brancacci: Érotique et théorie du plaisir chez Antisthène . In: Marie-Odile Goulet-Cazé, Richard Goulet (ed.): Le cynisme ancien et ses prolongements . Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 1993, ISBN 2-13-045840-8 , pp. 35-55

- Pedro Pablo Fuentes González. In defensa del encuentro entre dos Perros, Antístenes y Diógenes: historia de una tensa amistad . In: Cuadernos de Filología Clásica: Estudios Griegos e Indoeuropeos . 23, 2013, pp. 225–267 (reprint: in V. Suvák [ed.], Antisthenica Cynica Socratica, Oikoumene, Praha 2014, pp. 11–71)

- Gabriele Giannantoni: Antistene fondatore della scuola cinica? In: Marie-Odile Goulet-Cazé, Richard Goulet (ed.): Le cynisme ancien et ses prolongements . Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 1993, ISBN 2-13-045840-8 , pp. 15-34

portrait

- Gisela Richter : The Portraits of the Greeks II (1965) 180 fig. 1034-1039.

- Gisela Richter: The Portraits of the Greeks , Supplement (1972) Fig.1055.1056.

- Nikolaus Himmelmann : Antisthenes , in: B. Andreae, (Ed.) Phyromachos -problem, 31. Ergh. Communications from the DAI, Roman Department (1990) 13-24.

- Bernard Andreae : The Antisthenes statuette in Naples , in: B. Andreae (Hrsg.): Phyromachos problems , 31. Ergh. Communications from the DAI, Roman Department (1990) 80-82.

- L. Seemann (Koch): The seated statuettes of Antisthenes and Pittakos from Pompeii , Archäologischer Anzeiger 1993, 263-269.

Web links

- Julie Piering: Antisthenes. In: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Karl Barlen: Antisthenes and Plato , Struder'sche Buchdruckerei & Buchhandlung, Neuwied 1881

- Karl Müller (Ed.): Fragmenta historicorum Graecorum . Victor Langlois, Paris 1841–1870, 5 volumes ( Scriptorum graecorum bibliotheca , volumes 34, 37, 40 and 59), new editions 1875–1885, 1928–1938, reprint Frankfurt am Main, 1975.

- August Wilhelm Winckelmann (Ed.): Antisthenis. Fragmenta . Meyer and Zeller, Zurich 1842

Footnotes

- ↑ inventory number 288; Further information on this portrait can be obtained from Arachne, for example

- ^ Klaus Döring: Antisthenes . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Volume 2/1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, pp. 268–280, here: p. 269.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6.1.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6.2.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6: 18-19.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6.4.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6.1.

- ↑ inventory number 1838; more information on this portrait at Arachne

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6:13.

- ^ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6: 8.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6:13.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6:14.

- ↑ Xenophon, Symposium (Banquet) 4.

- ↑ Xenophon, Symposium (Banquet) 3.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6.2.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6.2.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6:13.

- ↑ Demosthenes , Against Aristocrates 213 ( online )

- ↑ Against the Sophists and Speech by Helen .

- ^ Andreas Patzer: Antisthenes der Sokratiker , partial print, dissertation Heidelberg 1970, pp. 238–246.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6,7.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 3.35. In 6:16 there is a dialogue called Sathon , which Athenaios also mentions twice (5,220d and 11,507a).

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6: 14-15 and 19.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6.4.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6: 15-18.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6.2.

- ^ Klaus Döring: Antisthenes . In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Volume 2/1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, pp. 268–280, here p. 271.

- ^ Andreas Patzer: Antisthenes der Sokratiker , partial print, dissertation Heidelberg 1970, pp. 51–53 and 107–163, see also pp. 91–107.

- ↑ See Th. Birt: Das antike Buchwesen , Bonn 1974, p. 449.

- ^ Andreas Patzer: Antisthenes der Sokratiker , partial print, dissertation Heidelberg 1970, pp. 118–122.

- ^ Andreas Patzer: Antisthenes der Sokratiker , partial print, dissertation Heidelberg 1970, pp. 123-124.

- ^ Andreas Patzer: Antisthenes der Sokratiker , partial print, dissertation Heidelberg 1970, p. 127.

- ^ Andreas Patzer: Antisthenes der Sokratiker , partial print, dissertation Heidelberg 1970, p. 45.

- ^ Klaus Döring: Antisthenes . In: Hellmut Flashar: Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Volume 2/1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, pp. 268–280, here: p. 271.

- ↑ See Klaus Döring: Antisthenes . In: Hellmut Flashar: Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Volume 2/1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, pp. 268–280, here: pp. 278–280.

- ^ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6: 8.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6:10.

- ^ Karl Müller : Fragmenta historicorum Graecorum , 2, 283, 51.

- ↑ See Xenophon, Symposion (Banquet) 3-4.

- ↑ Cf. Heinz Schulz-Falkenthal: On the work ethic of the Cynics . In: Margarethe Billerbeck (ed.): The cynics in modern research . BR Grüner, Amsterdam 1991, pp. 287-303.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6.2.

- ↑ Johannes Tzetzes, Chiliades 6,606.

- ↑ Simplikios , Commentary on the categories of Aristotle 208, 28. Cf. also Ammonios Hermeiou , Commentary on the Isagoge des Porphyrios 40.6 and the Scholien zu Aristotle , pp. 66, 68. Diogenes Laertios tells a very similar story about Diogenes von Sinope in On the life and teachings of famous philosophers 6, 53. This is said to have said: "Table and cup, Plato, I see, but tableness and cupiness at all", to which Plato is said to have answered: "That is clear, because eyes, to see table and cup, you have understanding, but not to look table and cup. "

- ^ Andreas Graeser : History of Philosophy . Volume 2: The Philosophy of Antiquity 2 , Beck, Munich 1993 (2nd edition), p. 56.

- ↑ The word logos can also be translated here as “definition”.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6.3.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 3.35.

- ^ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 9:53.

- ↑ What is probably meant is Plato, Euthydemos 286c.

- ↑ Aristotle, Topik 104b20.

- ^ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6: 8.

- ^ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6: 8.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6.2.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of Famous Philosophers 6: 1-19.

- ↑ Xenophon, Memorabilia (Memories of Socrates) 3, 11, 17 and 2.5.

- ↑ Whether Xenophon's reports can be viewed more as literary-fictional or as historically reliable eyewitness reports (as Xenophon claims) is controversial, the tendency today is more towards the former. Cf. Andreas Patzer: Antisthenes der Sokratiker , partial print, dissertation Heidelberg 1970, pp. 46–50.

- ^ Andreas Patzer: Antisthenes der Sokratiker , partial print, dissertation Heidelberg 1970, p. 13.

- ↑ Plato, Sophist 251b3

- ^ Plato, Phaedo 59b.

- ↑ Epiktet, educational conversations 1,17,12; 2,17,35; 3,24,67; 4,6.20.

- ^ Cicero, Tusculanae disputationes 5.26.

- ↑ Carl Werner Müller: Cicero, Antisthenes and the pseudoplatonic 'Minos' on the law (PDF; 4.2 MB) . In: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie , Volume 138, 1995, pp. 247–265, here: p. 248

- ^ Klaus Döring: Antisthenes . In: Hellmut Flashar: Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity , Volume 2/1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, pp. 268–280, here: p. 268.

- ^ Andreas Patzer: Antisthenes der Sokratiker , partial print, dissertation Heidelberg 1970, pp. 11-13.

- ^ Andreas Patzer: Antisthenes der Sokratiker , partial print, dissertation Heidelberg 1970, pp. 14-15.

- ↑ A comprehensive and detailed overview of writings and collections of sources on Antisthenes is given by Andreas Patzer: Antisthenes der Sokratiker , partial print, dissertation Heidelberg 1970, pp. 16–44.

- ^ Andreas Patzer: Antisthenes der Sokratiker , partial print, dissertation Heidelberg 1970, p. 17.

- ^ Wilhelm Gottlieb Tennemann: History of Philosophy , Volume 2, Barth, Leipzig 1799, pp. 87-99.

- ↑ August Wilhelm Winckelmann (ed.): Antisthenis Fragmenta , Meyer and Zeller, Zurich 1842.

- ^ Karl Barlen: Antisthenes and Plato , Struder'sche Buchdruckerei & Buchhandlung, Neuwied 1881.

- ↑ K. Urban: About the mentions of the philosophy of Antisthenes in the Platonic writings , Königsberg 1882.

- ↑ Karl Joël: The real and the xenophontic Socrates , 2 volumes, 1893-1901.

- ↑ An overview of the reception of Antisthenes is given in the introduction written by the editor in: Margarethe Billerbeck (Ed.): Die Kyniker in der moderneforschung , BR Grüner, Amsterdam 1991, pp. 1–30.

- ↑ Eduard Zeller: The philosophy of the Greeks in their historical development. Second part, first division. Socrates and the Socratics, Plato and the old academy . 3rd edition, Fues, Leipzig 1875, pp. 240–287.

- ^ Theodor Gomperz: Greek thinkers . Volume 2, 4th edition of the 1922-1931 reprint, De Gruyter, Holland 1973, p. 122.

- ↑ Donald R. Dudley: A History of Cynism . Methuen & Co., London 1937.

- ↑ Kurt von Fritz: Antistene e Diogene. Le loro relazioni reciproche e la loro importanza per la setta cinica . In: Margarethe Billerbeck (ed.): The cynics in modern research . BR Grüner, Amsterdam 1991, pp. 59-72.

- ↑ Margarethe Billerbeck (ed.): The cynics in modern research . BR Grüner, Amsterdam 1991, pp. 8-9.

- ^ Heinz Schulz-Falkenthal: On the work ethic of the Cynics . In: Margarethe Billerbeck (ed.): The cynics in modern research . BR Grüner, Amsterdam 1991, pp. 287-303.

- ↑ Nikolaus Himmelmann : Antisthenes. In: Bernard Andreae: Phyromachos problems. Zabern, Mainz 1990, ISBN 3-8053-1126-5 , pp. 13-23; Bernard Andreae : The Roman copies in marble after Greek masterpieces in bronze as an expression of Roman culture . In: Studi italiani di filologia classica . Volume 10, 1992, pp. 21-31.

- ↑ www.brindisiweb.it .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Antisthenes |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | ancient Greek philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 445 BC Chr. |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Athens |

| DATE OF DEATH | around 365 BC Chr. |