Diogenes of Sinope

Diogenes of Sinope ( ancient Greek Διογένης ὁ Σινωπεύς Diogénēs ho Sinōpeús , Latinized Diogenes Sinopeus ; * probably around 413 BC in Sinope ; † probably 323 BC in Corinth ) was an ancient Greek philosopher . He belongs to the current of cynicism .

Sources

Hardly any reliable data have been preserved about the historical Diogenes. Almost all information was passed down in the form of anecdotes , the truth of which is the subject of scientific speculation. The earliest source on Diogenes is a short passage from Aristotle , the most important by far is the doxographer Diogenes Laertios , who did not work until the 3rd century and whose report is based on numerous older authors - whose information was contradicting each other even then. Overall, the ancient reports on Diogenes are above average in number, especially in popular philosophical writings and in colored writing . The reliability of all testimonies about Diogenes is disputed; Legends probably formed during his lifetime, and it can be assumed that a number of anecdotes have been invented since his death.

Life

The dates of Diogenes' life are unknown, there are various, partly contradicting information available. After evaluating the relevant evidence, it is assumed that Diogenes was born towards the end of the 5th century BC. BC, possibly around the year 410 BC Was born in Sinope on the Black Sea and around the beginning of the 320s BC. Died in Athens or Corinth. Diogenes Laertios reports different information about the cause of death: consumption of a raw polyp, biliary colic , intentional holding of breath, dog bite.

According to an ancient tradition, Diogenes was a pupil of Antisthenes . If this is the case, then it must be no later than the early 360s BC. Moved to Athens. In modern research, however, the alleged student relationship with Antisthenes is controversial. Only moving to Athens is certain. The reasons for this are unclear, even if various anecdotes and stories have come down to it. Diogenes Laertios and several other authors report the legend that he fled or was banished because he himself or his father forged coins as a banker or official of the Sinope Mint. In Athens he made the acquaintance of the famous philosophers of his time: Plato , Aeschines of Sphettus , Euclid of Megara . On the other hand, the encounter with Aristippus of Cyrene may have been invented.

Stay in Corinth

In the ancient reports it is often mentioned that Diogenes stayed in Corinth. How often and for how long is unclear, at least he should have died there (according to other versions, however, in Athens). There are also legends surrounding this relocation. According to one, Diogenes is said to have been kidnapped by pirates while on a boat trip to Aegina and bought as a slave by a Corinthian named Xeniades in Crete . Xeniades then made him his caretaker and tutor of his sons. In Corinth he is said to have met the tyrant Dionysios II of Syracuse and, according to the most famous of the anecdotes, also Alexander the Great . Whether this encounter actually took place and also in this form is controversial. The anecdote appears in numerous ancient authors in often different variations and became a popular motif in the visual arts; the oldest surviving version comes from Cicero , Plutarch reports in more detail :

“The Greeks [...] decided to undertake a campaign with Alexander against the Persians, whereby he had also been appointed commander-in-chief. Since many statesmen and philosophers came to him on this occasion and wished him luck, he thought that Diogenes of Sinope, who was just in Corinth, would do the same. But the latter remained undisturbed in his rest in the Kraneion [place in Corinth] without bothering in the least about Alexander; therefore he went to Diogenes. Diogenes was just lying in the sun. But when so many people came up to him, he stretched himself up a little and stared at Alexander. The latter greeted him friendly and asked what he could do to help him. ' Go away from me, ' he replied, ' a little out of the sun! 'Alexander is said to have been so affected by this and, despite the contempt he was shown, admired the man's pride and greatness so much that when his companions joked and laughed about it as they walked away, he exclaimed:' Truly, I would not be Alexander, I would like to be Diogenes. '“

Doggy way of life

His nickname ὁ κύων ho kýōn ("the dog") was originally probably intended as a swear word related to his shamelessness. But Diogenes found it appropriate and has since called himself that. One of the many anecdotes related to this epithet is that Alexander the Great is said to have introduced himself to Diogenes as follows: "I am Alexander, the great King." To which Diogenes is said to have said: "And I Diogenes, the dog."

Diogenes is said to have voluntarily led the life of the poor and put it on public display. Allegedly he did not have a permanent residence and spent the nights in different places, such as public arcades . A storage vessel ( πίθος , pithos ) is said to have served him as a sleeping place, hence the winged word of Diogenes in the barrel or in the barrel. According to Diogenes Laertios, Diogenes' equipment included a simple woolen coat, a backpack with provisions and some utensils as well a stick. According to an anecdote, he is said to have thrown away his drinking cup and his eating bowl when he saw children drinking from their hands and storing lentil porridge in a hollowed-out loaf. He lived on water, raw vegetables, wild herbs, beans, lentils, olives, figs, simple barley bread and the like.

In Diogenes' time it was considered indecent in Greece to eat in public. But he not only did this, but also satisfied his sexual instinct in front of everyone, for the sake of simplicity by masturbation . According to an anecdote, he is said to have wished that he could also satisfy the feeling of hunger by simply rubbing his stomach.

Fonts

Diogenes Laertios provides two different lists of the writings of Diogenes that were circulating at the time. The first list includes 13 dialogues, 7 tragedies and letters, the second, from Sotion of Alexandria , 12 dialogues, chrien and letters. According to Sosicrates of Rhodes and Satyros of Kallatis , according to Diogenes Laertios, Diogenes did not write any writings at all.

Teaching

Since his writings have been lost and reports on philosophical positions represented by Diogenes are far rarer than the numerous anecdotes that have come down to us, his philosophical views are only known in broad outline. It can be assumed that Diogenes took the fundamental view that only those can be really happy who, firstly, free themselves from superfluous needs and, secondly, are independent of external constraints. A central concept is the self-sufficiency (autárkeia) that results from this : "It is divine not to need anything, and God-like to have little need."

Needlessness

Diogenes recognized only the basic needs for food, drink, clothing, shelter and sexual intercourse. All needs going beyond this should be put aside, so he is said to have even trained against the dispensable needs: To harden himself physically, he wallowed in scorching hot sand in summer and hugged snow-covered statues in winter. And in order to harden himself mentally, he trained not to get wishes fulfilled by begging stone statues for gifts. This natural plague (pónoi) differentiated Diogenes from the more common useless plague, the aim of which was to obtain fictitious goods. Finally, several anecdotes show that Diogenes not only rejected comfort, but also regarded it as the cause of many evils of his time.

Pleasure ( ἡδονή hēdonḗ ) and sensations of pleasure seems to have been viewed by Diogenes neither as particularly valuable, nor as absolutely necessary, but he accepted, for example, the pleasure that is felt during sexual activity as at least inevitable. Sexual activity (such as masturbation) is in any case natural and an elementary need.

Independence from external constraints

Sexual and spouse

Sexual intercourse with women was an example of Diogenes' dependence on other people, and a number of anecdotes are said to have a certain misogyny. Even so, he recognized the necessity of intercourse for human survival. Diogenes therefore did not hold on to marriage, which in his view was too close a bond - like Plato, however, he advocated the establishment of the community of women and children.

Social conventions, government and religion

Diogenes saw social conventions as an external compulsion, some of which he rejected in a radical way. We've already mentioned things like public masturbation and other provocative violations of good manners. Diogenes is said to have represented other, extremely offensive points of view in his writings. In one of his writings, the Politeia , he is said to have stated that nothing speaks against eating deceased people and children slaughtered as victims and that sexual relationships with mothers, sisters, brothers and sons are permitted. Herodotus already reported in some places about man-eating peoples, tribes that were used to community of women, others where it was the custom to eat their deceased parents and still others where people were sacrificed. It was also known that (whether true or not) sexual intercourse between sons and mothers was common among the Persians. These facts led him to regard the social prohibitions and conventions in question as the mere product of various practiced habits, which had become established as laws (nómoi) , customs and practices. The resulting constraints are not inherently correct, but rather prevent them from leading a happy life. Like Heracles, one must override these constraints. Whether Diogenes wanted in all seriousness to urge his own parents to eat and to have sexual relations with siblings or whether he merely wanted to point out the nullity of external constraints that prevent the individual from being happy can no longer be clarified. It is to be assumed that the tragedies that have not survived were about similar taboos.

Also in the Politeia it would entail the suspension have demanded form of government at that time known as "the only true political order is the order in the cosmos." So Diogenes to himself as one of the first citizen of the world (κοσμοπολίτης, cosmopolitan) designated and thus a cosmopolitanism represented to have. Diogenes' religious views are unknown, based on a few anecdotes, one can assume a mocking and ironic distance from religious questions.

Education, Dialectics and Philosophy

The disciplines of traditional education (such as grammar, rhetoric, mathematics, astronomy, and music theory) were viewed by Diogenes as useless and superfluous. In contrast to Antisthenes, he even considered the preoccupation with questions of dialectics (today the discipline of logic ) to be pointless and countered it with common sense. In some places, logical arguments in the form of conclusions have been passed down, but these can be understood less as a serious preoccupation with logic and more as perhaps even a mocking game with logical operations and purely logical justifications of certain views:

| Everything belongs to the gods. | |

| The gods are friends of the wise. | |

| Everything is common to friends. | |

| It follows: | Everything belongs to the wise. |

| If breakfast is nothing strange as such, then it is nothing strange in the marketplace either. | |

| But breakfast is nothing strange. | |

| It follows: | So there is nothing strange in the marketplace either. |

Diogenes thought little of other philosophers. Although he highly valued the teachings of Antisthenes and built on them, he disagreed with the person of Antisthenes and his implementation of his teachings. He is said to have described it as soft and compared it to a trumpet, which makes loud notes but cannot hear itself.

Diogenes and Plato

According to Diogenes Laertios, Diogenes' relationship to Plato may not have been the best. Diogenes tried to ridicule his doctrine of ideas as follows: “When Plato let himself be heard about his ideas and talked about a table and a cup, Diogenes said: 'As for me, Plato, I see a table and a cup, but a gracefulness and cupidity now and never more. ' Then Plato: 'Very understandable; for you certainly have eyes with which one can see cup and table; but you do not have a mind with which you can see tableiness and cupiness. '”Even Plato's efforts to define various terms he did not seem to have taken very seriously:“ When Plato established the definition, man is a featherless bipedal animal, and so that it would be applauded, Diogenes plucked the feathers of a rooster and brought it to its school with the words: 'This is Plato's man'; consequently the addition was made 'with flat nails'. "

reception

Philosophy and cultural historians as well as artists portray Diogenes as the one who did not primarily put forward theses, but instead put his own knowledge into practice publicly and demonstratively. The term “action philosopher” is occasionally used in this context.

philosophy

From the ranks of the philosophers, Diogenes received both the utmost approval and strict rejection. So Plato allegedly called him with defamatory intent a "mad Socrates." Hegel not only criticized Diogenes' closeness to the people, he also accused him of taking "unimportant things too seriously". This includes the publicly exhibited needlessness. In that Friedrich Nietzsche saw in it merely a “remedy against all ideas of social subversion ”, he denied the ancient philosopher's subversiveness .

Michel Foucault, on the other hand, saw the cheeky escapades and radical freedom that Diogenes took with them as the greatest possible chance for truth ( parrhesia ): “The courage to truth on the part of those who speak and take the risk, despite everything, the whole To tell the truth that he thinks. ”While Plato tries to downgrade Diogenes in comparison to Socrates, Peter Sloterdijk puts him on a par with him and interprets the“ bizarre things of his behavior ”as“ an attempt to comedically outdo the cunning dialectician. ” Ulf Poschardt brings Diogenes very close to our present in his phenomenological study of coolness and draws a direct connection to pop culture: Diogenes lived as loud as a pop star . According to both interpretations - according to Harry Walter - Diogenes "with his public lying sideways represents a culture of gestural subversion ."

In 1986 Natias Neutert translated the idea of subversion into a one-person theater piece in which he is both author and actor. He shows how the “body philosophy that transcends heroic history” can also nowadays be able to reduce “the poses of great truth” to absurdity .

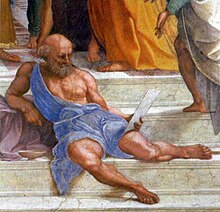

Art and fiction

The cultural and historical exception of Diogenes is reflected in a wealth of artistic representations, both pictures and sculptures.

Three statuettes of the same type, which are no longer complete and are believed to represent Diogenes, have survived: they show a bearded, naked man bent over. One of these statuettes was found in the Villa Albani in Rome . However, only the head, torso, shoulders and right thigh are original; everything else was added later. Of the other two statuettes there are only fragments of the legs, but they also contained fragments of a dog and a rucksack , which are typical attributes of Diogenes.

A well-preserved mosaic from the 2nd century shows Diogenes in his barrel , underneath his name can be read. The mosaic is now in the Roman-Germanic Museum in Cologne.

Wilhelm Busch put a humorous monument typical of him in his picture story Diogenes and the Bad Boys of Corinth , which contributed significantly to his popularity .

Source collections

expenditure

- Gabriele Giannantoni (Ed.): Socratis et Socraticorum Reliquiae , Volume 2, Bibliopolis, Naples 1990, ISBN 88-7088-215-2 , pp. 227-509 ( online )

- Bruno Snell (Ed.): Tragicorum Graecorum Fragmenta . 2nd Edition. Volume 1, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1986 (under the number 88: Diogenes Sinopensis you will find all testimonies relating to Diogenes' tragedies)

Translations

- Georg Luck (ed.): The wisdom of dogs. Texts of the ancient Cynics in German translation with explanations (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 484). Kröner, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-520-48401-3 , pp. 76-193.

- Diogenes Laertius of the Lives and Opinions of Famous Philosophers. From the Greek by August Christian Borheck . First volume, Vienna and Prague by Franz Haas 1807. Second chapter: Diogenes , p.346 books.google - p. 377, digital.onb.ac.at

literature

Overview representations

- Klaus Döring : Diogenes from Sinope. In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy . The philosophy of antiquity. Volume 2, half volume 1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, ISBN 3-7965-1036-1 , pp. 280-295.

- Michael Erler : The Cynics. In: Bernhard Zimmermann , Antonios Rengakos (Hrsg.): Handbook of the Greek literature of antiquity. Volume 2: The Literature of the Classical and Hellenistic Period. CH Beck, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-406-61818-5 , pp. 302-311, here: 303-305

- Marie-Odile Goulet-Cazé: Diogène de Sinope. In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques. Volume 2, CNRS Éditions, Paris 1994, ISBN 2-271-05195-9 , pp. 812-823

- Heinrich Niehues-Pröbsting : Diogenes of Sinope. In: Franco Volpi (Hrsg.): Großes Werklexikon der Philosophie. Volume 1, Kröner, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 3-520-82901-0 , pp. 400-401.

Investigations

- Klaus Döring: The Cynics. Buchner, Bamberg 2006, ISBN 3-7661-6661-1 .

- Niklaus Largier: Diogenes the Cynic. Examples, narration, history in the Middle Ages and early modern times. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1997, ISBN 3-484-36536-6 .

- Oliver Overwien: The sayings of the Cynic Diogenes in the Greek and Arabic tradition. Steiner, Stuttgart 2005, ISBN 3-515-08655-2 .

reception

- Joachim Jacob, Reinhard M. Möller: Diogenes. In: Peter von Möllendorff , Annette Simonis, Linda Simonis (ed.): Historical figures of antiquity. Reception in literature, art and music (= Der Neue Pauly . Supplements. Volume 8). Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 2013, ISBN 978-3-476-02468-8 , Sp. 361–372.

- Klaus Herding : Diogenes as a fool . In: Peter K. Klein and Regine Prange (eds.): Zeitenspiegelung. On the importance of traditions in art and art history. Festschrift for Konrad Hoffmann . Dietrich Reimer Verlag, Berlin 1998, pp. 151-180 ISBN 978-3-496-01192-7

Philosophical essays

- Karl-Wilhelm Weeber : Diogenes. The message from the bin. Nymphenburger, Munich 1987, ISBN 3-485-00552-5 .

- Karl-Wilhelm Weeber: Diogenes. The thoughts and deeds of the cheekiest and most unusual of all Greek philosophers. 4th edition. Nymphenburger, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-485-00890-7 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Diogenes von Sinope in the catalog of the German National Library

- Julie Piering: Diogenes. In: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- The younger cynics: Diogenes, Krates, etc. a. (Karl Vorländer, History of Philosophy, 1902 - online version)

- Diogenes from Sinope - some quotes

- Wilhelm Busch on Diogenes

Remarks

- ↑ Cf. Georg Luck: The wisdom of dogs. Texts of the ancient Cynics in German translation with explanations , p. 132

- ^ Klaus Döring: Diogenes from Sinope. In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity. Volume 2/1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, pp. 280–281.

-

↑ At the time of the 113th Olympiad (328 to 325 BC) he was an old man (Diogenes Laertios, On the life and teachings of the philosophers 6,79).

He died on the same day (June 13, 323) as Alexander the Great (Diogenes Laertios, On the life and teachings of the philosophers 6,79).

He was 81 years old ( Censorinus , De die natali 15.2).

He was about 90 years old (Diogenes Laertios, On the life and teachings of the philosophers 6,76).

His spiritual heyday was 396 (Eusebius of Caesarea, Chronik Ol. 96.1) or 392 ( Chronicon Paschale , a. U. C. 362.1). - ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6:77

- ^ Klaus Döring: Diogenes from Sinope. In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity. Volume 2/1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, p. 282.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the life and teachings of the philosophers 6: 76-77.

- ↑ See Marie-Odile Goulet-Cazé: Diogène de Sinope. In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 2, Paris 1994, pp. 812–823, here: 815; Klaus Döring: Diogenes from Sinope. In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The Philosophy of Antiquity , Volume 2/1, Basel 1998, pp. 280–295, here: 282–284; Gabriele Giannantoni: Antistene fondatore della scuola cinica? In: Marie-Odile Goulet-Cazé, Richard Goulet (ed.): Le cynisme ancien et ses prolongements , Paris 1993, pp. 15-34.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6: 20-21.

- ↑ For the biography of Diogenes see Klaus Döring: Diogenes from Sinope. In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity. Volume 2/1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, pp. 281–285.

- ↑ For example in Diogenes Laertios, About the life and teachings of the philosophers 6,74.

- ↑ See for the different versions of this legend Marie-Odile Goulet-Cazé: Xéniade de Corinthe. In: Richard Goulet (ed.): Dictionnaire des philosophes antiques , Volume 7, Paris 2018, pp. 190–192.

- ↑ Plutarch , Timoleon 15: 8.

- ^ Cicero, Tusculanae disputationes 5,92.

- ^ Klaus Döring: Diogenes from Sinope. In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity. Volume 2/1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, p. 289.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Lives and Teachings of the Philosophers 6.60.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6: 22-23 and 105; Seneca , Epistulae morales ad Lucilium 90,14: dolium.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6: 22-23

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6:37.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6:48.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6.55.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios , On the Lives and Teachings of the Philosophers 6:25.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6:46 and 69.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6.80.

- ^ Klaus Döring: Diogenes from Sinope. In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity. Volume 2/1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, pp. 285–287.

- ^ Klaus Döring: Diogenes from Sinope. In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity. Volume 2/1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, pp. 287–288.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6.105.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6:23.

- ↑ Plutarch, De vitioso pudore 531 f .; Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6:49.

- ^ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6:71.

- ^ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6:71.

- ^ Galenos , De locis affectis 6:15.

- ^ Klaus Döring: Diogenes from Sinope. In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity. Volume 2/1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, p. 290.

- ↑ Herculaneum Papyri , 155/339 col. XVI 20-24; see. Theophilus , Apologia ad Autolycum 3.5; Diogenes Laertios, On the life and teachings of the philosophers 6,73.

- ↑ Herculaneum Papyri , 155/339 col. XVIII 17-23.

- ↑ Herodotus, Historien 4,26

- ↑ On Diogenes' relationship to social conventions see Klaus Döring: Diogenes from Sinope. In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity. Volume 2/1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, pp. 290-292.

- ↑ Herculaneum Papyri , 155/339 col. XX 4-6.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6:72.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6,63.

- ^ Klaus Döring: Diogenes from Sinope. In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity. Volume 2/1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, pp. 292-293.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the life and teachings of the philosophers 6:73 and 6,103-104.

- ↑ After Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6:37 and 6:72.

- ↑ After Diogenes Laertios, On the life and teachings of the philosophers 6,69.

- ^ Klaus Döring: Diogenes from Sinope. In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity. Volume 2/1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, p. 294.

- ↑ Dion Chrysostomos , speeches from 8.1 to 2.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6.53.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6:40.

- ↑ Diogenes Laertios, On the Life and Teachings of the Philosophers 6.54. Peter Sloterdijk : Critique of Cynical Reason . First volume. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-518-11297-X , p. 209.

- ↑ See Ulf Poschardt : Cool . Frankfurt, Rogner & Bernhard bei Zweiausendeins, Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-0152-4 , p. 398.

- ↑ Quoted from Ulf Poschardt: Cool . Frankfurt, Rogner & Bernhard bei Zweiausendeins, Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-0152-4 , p. 398.

- ↑ Michel Foucault: The courage to truth. The government of self and others . II. Lectures at the Collège de France 1983/84, from the French by Jürgen Schröder, Suhrkamp Verlag Berlin 2010, ISBN 978-3-518-58544-3 , p. 29.

- ^ Peter Sloterdijk : Critique of Cynical Reason . First volume. Suhrkamp Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 3-518-11297-X , p. 208.

- ↑ Ulf Poschardt : Cool . Frankfurt, Rogner & Bernhard bei Zweiausendeins, Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-0152-4 , p. 45.

- ↑ Harry Walter: She said yes. I said pop. A lecture with photographs in: Walter Grasskamp / Michaela Krützen, Stephan Schmitt (Eds.): What is Pop? Ten attempts. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-596-16392-7 , pp. 55–56.

- ↑ Harry Walter: She said yes. I said pop. A lecture with photographs in: Walter Grasskamp / Michaela Krützen / Stephan Schmitt (eds.): What is Pop? Ten attempts. Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-596-16392-7 , p. 56.

- ↑ Cf. also ars longa vita brevis . Performance IV, catalog of the Künstlerhaus Bethanien , Berlin 1986, S, ISBN 3-923479-13-1 .

- ^ Klaus Döring: Diogenes from Sinope. In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity. Volume 2/1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, pp. 280–281.

- ^ Klaus Döring: Diogenes from Sinope. In: Hellmut Flashar (ed.): Outline of the history of philosophy. The philosophy of antiquity. Volume 2/1, Schwabe, Basel 1998, p. 281.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Diogenes of Sinope |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Greek philosopher, student of Antisthenes |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 400 BC Chr. |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Sinope |

| DATE OF DEATH | 324 BC BC or 323 BC Chr. |

| Place of death | Corinth |