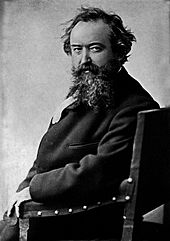

Wilhelm Busch

Heinrich Christian Wilhelm Busch (born April 15, 1832 in Wiedensahl , † January 9, 1908 in Mechtshausen ) was one of the most influential humorous poets and draftsmen in Germany. He also worked as a painter influenced by Dutch masters.

His first picture stories appeared from 1859 as single-sheet prints . They were first published in book form in 1864 under the title " Bilderpossen ". Famous all over Germany since the 1870s, he was considered a “classic of German humor” on his death thanks to his extremely popular picture stories. As a pioneer of comics , he created a. a. Max and Moritz , Fipps, the monkey , The pious Helene , Plisch and Plum , Hans Huckebein, the bad luck raven , the Knopp trilogy and other works that are still popular today. He often satirically picking up on the characteristics of certain types or social groups, such as the self-satisfaction and double standards of the philistine or the piety of clergy and laypeople. Many of his two-line lines have become fixed phrases in German , e.g. B. “Becoming a father is not difficult, but being a father is very difficult” or “This was the first trick, but the second will follow immediately”.

Wilhelm Busch was a serious and withdrawn person who lived in seclusion in the provinces for many years. He gave little value to his picture stories himself and called them “Schosen” ( French chose = thing, thing, quelque chose = something, anything). At the beginning he saw it only as a way of earning a living, with which he could improve his oppressive economic situation after dropping out of art studies and years of financial dependence on his parents. His attempt to establish himself as a serious painter failed because of his own standards. Wilhelm Busch destroyed most of his paintings; those that have been preserved often seem like improvisations or fleeting color notes and are difficult to assign to a particular painterly direction. His poetry and prose , influenced by the style of Heinrich Heine and the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer , met with incomprehension among the public, who associated his name with comical picture stories. He sublimated with humor that his artistic hopes were disappointed and that he had to lower excessive expectations of himself. This is reflected both in his picture stories and in his literary work.

Life

Family background

Johann Georg Kleine, the grandfather Wilhelm Busch on his mother's side, settled in the late 18th century in the small, rural town Wiedensahl between the foam-burg city of Hagen and the Hanoverian Kloster Loccum down. He bought a thatched half-timbered house there in 1817, in which Wilhelm Busch was born around 15 years later. Amalie Kleine, Wilhelm Busch's grandmother, ran a grocer's shop in the village, where Busch's mother Henriette helped out while her two brothers attended high school. Johann Georg Kleine died in 1820. His widow and her daughter continued to run the grocer's to ensure the family's livelihood. At the age of 19, Henriette Kleine married her father's successor, the surgeon Friedrich Wilhelm Stümpe, in her first marriage . Henriette Kleine was already widowed at the age of 26, and the three children from this connection had died as small children. Around 1830, the illegitimate farmer's son Friedrich Wilhelm Busch settled in Wiedensahl. He had completed a commercial apprenticeship in neighboring Loccum and initially took over the grocer's shop in Wiedensahl, which he modernized from the ground up.

Childhood (Wiedensahl)

Wilhelm Busch was born on April 15, 1832 as the first of seven children from the marriage between the pious Henriette Kleine and the constantly pipe-smoking Friedrich Wilhelm Busch in Wiedensahl . Six other siblings followed shortly afterwards. Fanny (1834), Gustav (1836), Adolf (1838), Otto (1841), Anna (1843) and Hermann (1845) all survived their childhood. The parents were ambitious, hardworking, and devout Protestants who achieved some prosperity in the course of their lives. Later they could afford to have two more of their sons study alongside Wilhelm. The willingness of Friedrich Wilhelm Busch to invest so heavily in the education of his sons, the Busch biographer Berndt W. Wessling attributes at least in part to his own illegitimate parentage, which was a significant social flaw, especially in the village area.

Busch's first reading as a seven-year-old boy was hymn book verses, stories from the Bible and fairy tales by Hans Christian Andersen .

The young Wilhelm Busch was tall, but of a rather delicate and delicate build. Boyish, rough pranks, as he later ascribed to his protagonists Max and Moritz , were rare in his childhood in Wiedensahl. Later, in his autobiographical sketches and letters, he described himself as a sensitive, fearful child who had “carefully studied anxiety” and who was fascinated, compassionate and disturbed when the domestic animals were slaughtered in autumn. The child's experience of the "terribly attractive" "metamorphosis in sausage" had such a lasting impact on Wilhelm Busch that he was disgusted with pork throughout his life.

In autumn 1841, after the birth of his brother Otto, the now nine-year-old Wilhelm Busch was entrusted to his maternal uncle, the 35-year-old pastor Georg Kleine in Ebergötzen , for upbringing. In addition to the limited space in the family home with many children, one reason for this was probably the father's wish to provide his son with a better education than the Wiedensahler village school, where up to 100 children were taught at the same time on 66 square meters. The next secondary school accessible from Wiedensahl was in Bückeburg, about 20 kilometers away . The Buschs would have had to place their son there as a boarder with a strange family. Pastor Kleine, on the other hand, who had just become a father himself, had a spacious parsonage in Ebergötzen and was predestined to take on the role of surrogate parent together with his wife Fanny Petri. In fact, Georg Kleine turned out to be a responsible and caring uncle, with whom Wilhelm Busch repeatedly found refuge in the years of his unsuccessfulness.

Wilhelm Busch received private lessons from his uncle, in which his new friend Erich Bachmann (1832–1907) was allowed to take part. Erich Bachmann was the son of the wealthiest miller in Ebergötzen and was the same age as Wilhelm Busch. The stays in the mill found their echo later in the stories of Max and Moritz ("ricke-racke, ricke-racke, the mill goes with crackling [...]"). The friendship with Erich Bachmann, which Wilhelm Busch later described as the longest and most inviolable of his life, found its literary echo in the story of Max and Moritz published in 1865. A small pencil portrait that Wilhelm Busch drew of his friend at the age of 14 shows Erich Bachmann as a chubby, self-confident boy who, like Max in this story, had a rough structure. Busch's self-portrait, created at the same time, shows a swirl of hair that became a perky one for Moritz.

It is not exactly known in which subjects Georg Kleine taught his nephew and his friend. As a theologian, Georg Kleine was an ancient speaker . In mathematics, Wilhelm Busch learned only the four basic arithmetic operations from his uncle . The science classes were probably a bit more extensive, because Georg Kleine was a beekeeper like many pastors of his time and wrote essays and specialist books about his hobby. Wilhelm Busch demonstrated his interest in beekeeping in later stories such as Die kleine Honigdiebe (1859) or Schnurrdiburr or Die Bienen (1872) (also in contributions in kind). Lessons also included drawing and later reading from German and English poets.

Wilhelm Busch had little contact with his birth parents during his boar idols. At that time, the distance of 165 kilometers between Wiedensahl and Ebergötzen corresponded to a three-day journey by horse and cart. The father came to visit once or twice a year. The mother stayed behind in Wiedensahl to look after the younger children. Wilhelm Busch did not return to visit his family until he was twelve. When they met again, the mother did not recognize her son at first. Some of Busch's biographers see the early alienation from his parents and especially his mother as the cause of Wilhelm Busch's later solitary bachelorhood.

Youth (Lüthorst)

In the fall of 1846, Wilhelm Busch and the Kleine family moved to Lüthorst ("Lüethorst"), where they moved into the local parish . There he was confirmed on April 11, 1847 , and there he stayed frequently until 1897, especially since his brother administered the adjacent domain of Hunnesrück . In September 1847 he began a mechanical engineering studies at the Polytechnic Hannover . Busch's biographers disagree on the reason why school education was discontinued at that moment. Most biographers take the view that this was done at the request of the father, who did not have sufficient understanding for his musically inclined son. Busch's biographer Eva Weissweiler suspects, however, that Pastor Georg Kleine also played a key role in this decision. In their opinion, possible triggers are Wilhelm Busch's friendly dealings with the innkeeper Brümmer, in whose restaurant there was political debate, and Busch's unwillingness to believe every word of the Bible and the catechism .

Studies (Hanover, Düsseldorf, Antwerp)

Despite initial difficulties in mastering the material, Busch studied from the age of 16 for almost four years at the "Polytechnic", the Technical University of Hanover , headed by Karl Karmarsch . In 1848, Busch and other "polytechnicians" took part in protective measures against revolutionaries who were building barricades under the leadership of the teachers. A few months before completing his studies, he confronted his parents with the desire to move to the Düsseldorf Art Academy . According to the report by Busch's nephew Hermann Nöldeke, it was mainly his mother who gave him support.

The father finally gave in, and in June 1851 Wilhelm Busch traveled to Düsseldorf to enroll at the art academy. To his disappointment, the 19-year-old Wilhelm Busch was not admitted to the class of advanced students there, but only entered preparatory classes, the “Classical Classes” (drawing according to antiquity) by Karl Ferdinand Sohn and “Lessons in anatomy” with Heinrich Mücke . Although the parents had paid tuition fees for one year, Wilhelm Busch quickly and increasingly stayed away from classes.

In May 1852 Wilhelm Busch left for Antwerp to continue his art studies at the Koninklijke Academie voor Schone Kunsten with Josephus Laurentius Dyckmans . He had convinced his parents with the (inapplicable) argument that studies in Antwerp were less schooled than in Düsseldorf and that he could study the old masters there. In Antwerp, where he lived “at the corner of the Käsbrücke with a beard trimmer ” and his wife, he saw paintings by Peter Paul Rubens , Adriaen Brouwer , David Teniers and Frans Hals for the first time. The paintings stoked his enthusiasm for painting (Busch described June 26, 1852 as the beginning of the more definite shaping of his “character as a person and painter”), but at the same time made him doubt his own painting abilities. Finally he broke off his studies in Antwerp.

Wiedensahl

After a severe typhus illness, his Antwerp hosts had nursed him back to health, he returned to Wiedensahl in 1853 penniless.

Wilhelm Busch, still badly affected by his illness, spent the next five months painting and collecting folk tales, sagas, songs, ballads , rhymes and fragments of local superstition . Busch's biographer Joseph Kraus rates this collection as a useful contribution to folklore because Wilhelm Busch not only recorded the narrator's peculiarities, but also the circumstances surrounding the narrative situation. Wilhelm Busch tried to publish this collection but could not find a publisher. The collection did not appear until after his death. During the Nazi era, it earned him the reputation of being a " national seer".

Munich

After Wilhelm Busch had spent another six months with his uncle Georg Kleine in Lüthorst, he wanted to continue his art studies in Munich. The wish led to a falling out with his father, who finally saw him off with a final payment to Munich. The expectations that Wilhelm Busch had attached to studying art in Munich were not met. For four years Wilhelm Busch let himself drift seemingly aimlessly. He kept returning to his uncle in Lüthorst, but had broken off contact with his parents. His situation seemed so hopeless that in 1857 and 1858 he considered emigrating to Brazil to breed bees there.

Wilhelm Busch made contact with the Munich art scene in the artists' association Jung München ( Theodor Pixis was president of the association ), in which almost all of the important Munich painters were united and for whose association newspaper he produced, among other things, caricatures and text for use. Busch and his club friends came together in Brannenburg for artistic studies. From 1876 to 1880 he was a member of the then already renowned artist society Allotria . Kaspar Braun , who published the satirical newspapers Münchener Bilderbogen and Fliegende Blätter , became aware of Busch and finally offered him a freelance work. Thanks to the fees, Wilhelm Busch was free of debt for the first time and had sufficient funds to support himself.

The first more intense relationship with a woman seems to have taken place at this time. In any case, this is indicated by a preserved self-caricature, which he dedicated to the “beloved in Ammerland”. His courtship for Anna Richter, a 17-year-old businessman's daughter who Wilhelm Busch met through his brother Gustav, failed in 1862. Anna Richter's father probably refused to entrust his daughter to an artist who was unknown at the time and who was without a regular income.

Wilhelm Busch's attempts as a librettist , which are now as good as forgotten , also fall in the early Munich years . By 1863 he had written three major stage works, two of which, and possibly the third , were set to music by Georg Kremplsetzer . Neither love and cruelty , a romantic opera by Motzhoven in three acts, nor the fairy tale play Hansel und Gretel (with the music by Georg Kremplsetzer) and The Cousin on Visit , a kind of opera buffa in nine scenes, were particularly successful. During the production of The Visiting Vetter , there were disputes between Busch and Kremplsetzer, so that Busch withdrew his name as an author and the play was only listed as a musical play by Georg Kremplsetzer on the theater bill .

Max and Moritz

Between 1859 and 1863 Wilhelm Busch wrote over a hundred articles for the Munich Bilderbogen and the Fliegende Blätter . Busch found his dependence on the publisher Kaspar Braun increasingly tight, so he looked for a new publisher in Heinrich Richter, the son of the Saxon painter Ludwig Richter . Heinrich Richter's publishing house had previously only published works by Ludwig Richter, as well as children's books and religious edification literature . Wilhelm Busch may not have been aware of this fact when he agreed with Heinrich Richter to publish a picture book. Wilhelm Busch was free to choose a topic, but Heinrich Richter had reservations about his four proposed stories. Heinrich Richter's misgivings were justified; the picture antics published in 1864 proved to be a failure.

Presumably as reparation for the financial loss suffered, Wilhelm Busch offered his Dresden publisher the manuscript of Max and Moritz and waived any fee claims. Heinrich Richter rejected the manuscript due to the lack of sales prospects. Eventually, Busch's old publisher Kaspar Braun acquired the rights to the picture story for a one-off payment of 1,000 florins. This corresponded to about two annual wages of a craftsman and was a proud sum for Wilhelm Busch. For Kaspar Braun, the business turned out to be a stroke of luck in publishing.

The sale of Max and Moritz was very sluggish at first. The sales figures only improved from the second edition in 1868, and in 1908, the year of Busch's death, the 56th edition and more than 430,000 copies had been sold. The work initially went unnoticed by the critics. It was only after 1870 that the educators of the Bismarckian era criticized it as a frivolous work that was harmful to young people.

Frankfurt am Main, also Wiedensahl, Lüthorst and Wolfenbüttel

With increasing economic success, Wilhelm Busch returned to Wiedensahl more and more frequently. Only a few of his acquaintances lived in Munich, the artists' association had since disbanded. Eventually Wilhelm Busch gave up his residence in Munich. In June 1867 Wilhelm Busch visited his brother Otto for the first time in Frankfurt am Main, where he was employed as a tutor for the wealthy Kessler family of bankers and industrialists. Busch quickly made friends with the landlady, Johanna Keßler. The mother of seven was an influential art and music patron in Frankfurt, who regularly held a salon in her villa on Bockenheimer Landstrasse , where painters, musicians and philosophers frequented. She believed she had discovered a great painter in Wilhelm Busch, and Anton Burger , the leading painter of the Kronberg painters' colony , supported her in this assessment. While she didn't like Wilhelm Busch's humorous drawings, she wanted to promote his painting career. She first furnished him an apartment and a studio in her villa. Later Wilhelm Busch took up his own apartment near the Kessler villa, in which a housekeeper from the Kessler family regularly checked on everything. Motivated by the support and admiration of Johanna Keßler, the Frankfurt years are considered the period in which Wilhelm Busch was most productive in painting. They are also among the most intellectually stimulated, since he dealt more intensively with the work of Arthur Schopenhauer through his brother and took part in Frankfurt's cultural life through Johanna Keßler.

Wilhelm Busch did not settle permanently in Frankfurt am Main. Towards the end of the 1860s he was constantly commuting between Frankfurt, Wiedensahl, Lüthorst and Wolfenbüttel , where his brother Gustav lived. The connection with Johanna Keßler lasted five years. After his return to Wiedensahl in 1872, he initially stayed with a pen friend, who fell asleep completely between 1877 and 1891. It was not until 1891, on the initiative of the Kessler daughters, that Wilhelm Busch and the meanwhile widowed Johanna Kessler came into contact again.

Saint Anthony of Padua and The Pious Helene

During the Frankfurt years, three self-contained picture stories were published, which were partly or wholly determined by Busch's anti-clerical attitude and which quickly found widespread use in Germany against the background of the Kulturkampf . As a rule, Wilhelm Busch did not see his stories as an opinion on questions of daily political affairs. In their satirical exaggeration of bigotry, superstition and stuffy double standards, at least two of the picture stories go far beyond the concrete historical context. The third picture story, Father Filucius , has a stronger reference to the time and was self-critically described by Wilhelm Busch as an "allegorical one-shot".

In St. Anthony of Padua , Wilhelm Busch turns against the image of the Catholic Church . The picture story appeared at the time when Pius IX. proclaimed the dogmas of papal infallibility , which the Protestant world rubbed extremely hard. The Moritz Schauenburg publishing house , which published Saint Anthony , was particularly closely monitored by the censors because of other publications . The public prosecutor's office in Offenburg used the publication of Busch's new picture story as an opportunity to indict the publisher Moritz Schauenburg on July 8, 1870 for “degrading religion and causing public nuisance through indecent writings”, which hit Wilhelm Busch very much. Particularly offensive were scenes in which the devil tries to seduce Antonius in the form of a slightly tucked ballet actress and Antonius is recorded in heaven together with a pig. Saint Anthony of Padua was confiscated. But on March 27, 1871, the court in Offenburg acquitted the publisher. In Austria, however, the work remained banned until 1902.

Moritz Schauenburg refused to publish the next picture story because he feared further charges. The pious Helene was brought out instead by Otto Friedrich Bassermann , whom Wilhelm Busch knew from his time in Munich. In the pious Helene , which soon appeared in other European languages, Wilhelm Busch satirically illuminates religious hypocrisy and dodgy civic morality:

- A good person likes to be careful

- Whether the other does something bad too;

- And aspire through frequent teaching

- After his improvement and conversion

Many details of the pious Helene reveal criticism of the Kessler family's concept of life. Johanna Keßler was married to a significantly older man and had her children raised by governesses and tutors while she played an active role in Frankfurt social life.

- I want to keep quiet about the theater

- As from there, late in the evening

- Beautiful mother, old father

- Going home arm in arm

- It is true that there are many children

- But you think nothing of it.

- And the children become sinners

- If the parents don't care.

The marriage of the clearly aged Helene with the rich GIC Schmöck also seems to be an allusion to Johanna Keßler's husband, who shortened his name to JDH Keßler . According to the Busch biographer Eva Weissweiler, Schmöck is derived from Schmock , a Yiddish swear word that means “fool” or “idiot”. Johanna Keßler will have understood this allusion, because her husband was completely uninterested in art and culture.

In the second part of the pious Helene , Wilhelm Busch attacks the Catholic pilgrimage . Accompanied by her cousin Franz, a Catholic priest, Helene, who had previously been childless, went on a pilgrimage. The pilgrimage shows success; after a due time, Helene gives birth to twins, whose similarity to her father makes it clear to the reader that the father is not Schmöck, but cousin Franz. Cousin Franz, however, comes to an early end when he is killed by the jealous valet Jean because of his interest in the female kitchen staff. The meanwhile widowed Helene is left with only rosary , prayer book and alcohol as a consolation of life. She ends when she falls drunk into a burning kerosene lamp. After Helene's tragicomic ending, the philistine Nolte formulates a moral sentence that is often interpreted as a fitting summary of Schopenhauerian wisdom:

- The good - this sentence is certain -

- Is always evil what you leave behind!

Father Filucius is the only picture story in the complete works that goes back to a suggestion by the publisher. It is considered the weakest of the three anticlerical picture stories. The story, which is directed against the controversial Jesuit order , aimedagain at an anti-Catholic buyersafter the success of St. Anthony and the pious Helene .

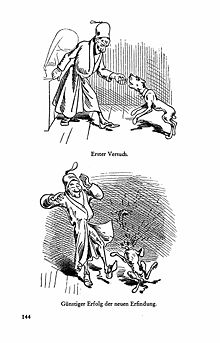

In Wilhelm Busch's work there are only a few other verse stories that relate to current events. Monsieur Jacques à Paris was one of these exceptions during the siege of 1870 . The Busch biographer Manuela Diers describes this picture story as "a tasteless work that serves anti-French affects and makes fun of the plight of the French in their capital besieged by the Prussian troops". It shows an increasingly desperate French citizen who, during the German siege of Paris, first ate a mouse as “domestic venison ”, then amputated the tail of his dog to cook it, and finally invented an “explosion pill” cost his dog and then two of his fellow citizens their lives. Eva Weissweiler points out, however, that Wilhelm Busch dealt ironic blows on all sides in his stories. With Eginhard and Emma (1864), a fictional family episode from the life of Charlemagne , he ridiculed the enthusiastic call for a German Empire on the foundations of the Holy Roman Empire and courtly Catholicism; In The Birthday or the Particularists, he ironized the fanatical anti-Prussian sentiment of his Hanoverian compatriots.

Criticism of the heart

When Wilhelm Busch left Frankfurt, he refrained from drawing further picture stories for a while and devoted himself mainly to his first purely literary text, the collection of poems Critique of the Heart . With his poems he wanted to show his readership as a new, serious Wilhelm Busch. The contemporary criticism reacted to the 81 poems mostly blankly to devastating. Even his long-time friend Paul Lindau found it difficult to gloss over the collection and cautiously called it “very serious, heartfelt, lovely poems”. His readership, on the other hand, reacted disturbed or even angry to the poems, which often dealt with marriage and sexuality.

Busch's driving force for the creation of this work was self-love and the desire for self-reflection and not just the pursuit of fame, honor and other things. His then publishing representative Bassermann wrote to Busch: "The criticism of the heart seems to cause a real storm in the press." Nevertheless, there were only a few positive reviews. The fact that this work was unsuccessful was mostly due to the fact that it did not correspond to the ideas of the poetry of the time.

Busch said of the work Critique of the Heart :

"In small variations on an important theme, these poems are intended to bear witness to my and our evil hearts."

The image of the man in naked youth

- The image of the man in naked youth

- So proud in peace and moved so nobly,

- It is a sight that inspires admiration;

- So bring light! And remember, oh skull!

- But a woman, an undisguised woman -

- It'll be very different for you, old boy.

- Admiration runs through the whole body

- And grabs your heart and lungs with fright.

- And suddenly the blood let loose chases

- Through all the streets, like the fire riders.

- The whole fellow is a bright ember;

- He no longer sees anything and just pats on.

Did you see the wonderful picture of Brouwer ?

- Did you see the wonderful picture of Brouwer?

- It attracts you like a magnet.

- You are smiling, meanwhile, a shock of horror

- Goes through your spine.

- A cool doctor opens the door to a man

- The blackness at the back of the neck;

- Next to it stands a woman with a jug

- Immersed in this misfortune.

- Yes, old friend, we have our love

- Mostly in the back. And full of peace of mind

- Presses it on another. It's running down

- And strangers watch.

Eva Weissweiler does not rule out that an increasing alcohol addiction prevented Busch from dealing self-critically with his work. However, he seemed to be aware of his problem. Wilhelm Busch increasingly turned down invitations to celebrations at which alcohol was drunk. He had Otto Bassermann send him wine to Wiedensahl so that his addiction would go undetected in his immediate vicinity. He also showed more and more drinkers in his pictures. Alcohol wasn't his only addiction. In 1874 Wilhelm Busch, who was a heavy smoker, showed symptoms of severe nicotine intoxication.

Correspondence with Marie Anderson

In January 1875, the Dutch writer Marie Anderson contacted Wilhelm Busch by letter. She was one of the few who praised criticism of the heart and also planned to review the book for a Dutch newspaper. Wilhelm Busch reacted euphorically to her letter; between January and October 1875 they exchanged over fifty letters. Marie Anderson's letters have not survived except for one. Only Busch's letters addressed to them have survived in copies. Marie Anderson seems to have been a tireless questioner who motivated Wilhelm Busch to speak up on questions of philosophy, religion and morals.

-

To Mrs. Marie Anderson, Wiesbaden(Wiedensahl (Hanover), Jan. 20, 1875)

- Your judgment, madam, has been extremely flattering to me. Hopefully it will do well to the little book, which has often been rejected with a certain moral indignation, that a lady so kindly places her hand on it. - Please approve the affirmation of my utmost respect. * Criticism of the heart

In the course of time, Busch's form of address and the way of saying goodbye also changed. From the initial “Dear Ms. Anderson!” And “Kind regards! W. Busch “in the letter from Wiedensahl, July 25, 1875:

- Dear Mary! […] With a thousand regards, W. Busch.

Even when Busch was traveling, he always gave Ms. Marie Anderson his new address so that they could always stay in contact. On August 29, 1875, Busch wrote to Marie Anderson from Wiedensahl: Although I do not love vivisections , I will always remember you kindly.

In October 1875 the two of them met in Mainz for several hours. After the excursion, Wilhelm Busch returned to his publisher Otto Friedrich Bassermann in Heidelberg in a “terrible mood”. From his memories it is known that several family members suspected the cause of Busch's conspicuous behavior in a failed bridal show. There is actually no evidence that Wilhelm Busch sought a closer relationship with a woman after contacting Marie Anderson.

The correspondence was then continued for a while with a clear reserve and increasing intervals and ended entirely after three years.

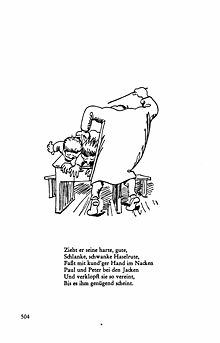

A bachelor's adventure

Despite the creative break after moving from Frankfurt, the 1870s were one of Wilhelm Busch's most productive years. In 1874 he published Dideldum! a collection of short picture stories. His Knopp trilogy appeared from 1875 . The bachelor's adventure was the first part, the sequels of which appeared as Mr. and Mrs. Knopp in 1876 and Julchen in 1877. For the first time, the citizen is not the victim of powerful nuisances, as was the case in Max and Moritz or Hans Huckebein, the unlucky raven , but rather the main character. Completely unpathetic, he lets his hero Tobias Knopp become aware of his own transience:

- Roses, aunts, bases, carnations

- Are compelled to wither;

- Oh - and finally also through me

- Make a big line

In order to face the emptiness of his existence, Tobias Knopp goes on a bridal lookout in the first part of the trilogy and visits his old friends, whom he always finds in unenviable marital relationships. Since he was not convinced by the example of the lonely hermit either, he returned home and made his housekeeper unceremoniously a marriage proposal, which, according to Busch's biographer Joseph Kraus, is the shortest in German literary history:

- Girl, - he speaks - tell me if -

- And she smiles: Yes, Mr. Knopp!

In depicting “marital merrymaking”, Wilhelm Busch went to the limit of what was possible with a publication that was freely available in bookshops in the 19th century. In the end, daughter Julchen became the purpose of their lives. And after Tobias Knopp has showered from one meal to the next for a happy married life and finally married his daughter, his life becomes completely meaningless again.

- Knopp he has down here now

- Actually nothing more to do. -

- It served its purpose. -

- His image of life becomes wrinkled. -

In the opinion of Busch's biographer Berndt W. Wessling , Wilhelm Busch's Knopp trilogy wrote off his desire for marriage. He found his housekeeper in his sister Fanny. To Marie Anderson he wrote: "I will never get married ... I have it good with my sister too."

Until the death of Fanny's husband, Pastor Hermann Nöldeke, he lived with Fanny's family in the rectory. After the death of his brother-in-law in 1879, he had the parish widow's house rebuilt according to his ideas. There his sister ran the household for him, and he acted as the father of his three underage nephews. His sister would have preferred to live in a more urban setting because of her sons' education. According to the memories of his nephew Adolf Nöldeke, however, Wilhelm Busch linked his concern for the family to staying in Wiedensahl.

Living together with Wilhelm Busch did not offer Fanny Nöldeke and her three sons the idyll of Knopp's marriage. The years around 1880 in particular were a time of physical and mental crises for Wilhelm Busch. Wilhelm Busch could not bear a visit, so that Fanny Nöldeke had to cut off all contact with the village. He didn't invite friends like Otto Friedrich Bassermann , Franz von Lenbach , Hermann Levi or Wilhelm von Kaulbach to Wiedensahl, but met them in Kassel or Hanover . Although Busch had long been a wealthy man, Fanny Nöldeke had to manage the household without help. If his sister resisted his wishes, he became enraged. Wilhelm Busch was still addicted to alcohol. His picture story Die Haarpaket , published in 1878, addresses in nine individual episodes how people and animals get drunk. From the point of view of Busch biographer Eva Weissweiler, it is only superficially funny and harmless, a bitter study of addiction and the state of madness that it causes.

From 1873 Wilhelm Busch returned to Munich several times and took an intensive part in the life of the Munich artist society. It was his attempt not to withdraw too much into provincial life. In a final attempt to establish himself as a serious painter, he even had a studio in Munich from 1877. He ended his stays in Munich abruptly in 1881 after he had interrupted the event while he was in a vaudeville show with the von Lenbach family in a very intoxicated state and had made a scene at the social get-together that followed.

As for me

At the end of Busch's career as a draftsman of picture stories, the two works Balduin Bählamm, the prevented poet (1883) and painter Klecksel (1884) were created, both of which thematize artistic failure and are thus a kind of self-comment. Both stories each have an introductory preface, which Busch biographer Joseph Kraus believes are both bravura pieces of comic poetry . While in Balduin Bählamm the bourgeois hobby poet and the Munich poet circle Die Krokodile with its main representatives Emanuel Geibel , Paul von Heyse and Adolf Wilbrandt are mocked, the painter Klecksel aims primarily at the bourgeois art connoisseur, whose key to art is above all the price of Factory is.

- With a keen eye for connoisseurs

- First I look at the price

- And on closer inspection

- If the price increases, so does the respect.

- I look through the cupped hand

- I blink, nod: 'Ah, charming!'

- The coloring, the brushwork,

- The hues, the grouping,

- This chandelier, this harmony,

- A masterpiece of the imagination.

In 1886 the first biography about Wilhelm Busch appeared in the German book trade. The author Eduard Daelen , a painter and writer, was a vehement anti-Catholic of the opinion that he had found a like-minded person in Wilhelm Busch. When Über Wilhelm Busch and its significance appeared, both Busch and his circle of friends were embarrassed. In the bizarre laudation, Eduard Daelen equated Wilhelm Busch with greats like Leonardo da Vinci , Peter Paul Rubens and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and quoted uncritically from a non-binding correspondence with Busch. The literary scholar Friedrich Theodor Vischer , who met a few critical remarks in his essay "About newer German caricatures" in addition to a respectful appreciation of Busch, attacked Daelen in long tirades as "literary bigwigs" and accused him of the "envy of the dried up Philistine eunuch ". The literary historian Johannes Proelß was one of the first to respond to Daelen's biographical attempt . His essay, which appeared in the Frankfurter Zeitung , contained a number of incorrect biographical data and was the reason for Wilhelm Busch to comment on himself in the same newspaper.

The two newspaper articles that appeared in October and December 1886 under the title As For Me , tell the reader only the poorest. After all, Busch indicated that he was going through numerous dark hours: “The quiet, lonely, dark night is coming. It's about in the brain capsule and haunted through all bones, and you throw yourself from the hot corner of your pillow to the cold one and back and forth until the noise of the dawning morning seems like a musical pleasure to you. ”Analysts read from Busch's autobiographical essays a profound identity crisis emerged. Busch repeatedly revised his self-biographical statements in the years to come. The last version, which appeared under the title About Me , contains less biographical information than the first version As For Me, and also lacks the signs of bitterness and amusement about yourself that could still be seen in As For Me .

The last few years, Mechtshausen

The prose piece Eduards Traum was published in 1891. The text has no actual storyline, but consists of many small nested episodes. The judgments about this story differ widely. Joseph Kraus sees this story as the real highlight of Wilhelm Busch's life's work, the Busch nephews considered it a pearl of world literature, and the editors of the Critical Complete Edition state a narrative style that had no equivalent in the literature of his time. Eva Weissweiler, on the other hand, sees in the story Wilhelm Busch's unsuccessful attempt to prove himself in the genre of the novella , and believes that the polemical swipes against everything that annoyed and offended him expose psychological abysses that his picture stories can only guess at. The story Der Schmetterling , published in 1895, parodies themes and (fairy tale) motifs from German Romanticism and mocks their pious optimism about history based on Busch's illusion-free image of man based on Schopenhauer and Charles Darwin . Compared to Eduard's dream, the text is more stringent in its narrative style, but like the latter, it hardly found a readership because it seemed to fit so little with the overall works of Busch.

In 1896 Wilhelm Busch gave up painting for good and gave all rights to his publications to the Bassermann publishing house in return for a compensation of 50,000 marks . Busch felt old because he needed glasses to write and paint and his hands were shaking slightly. His sister Fanny Nöldeke also no longer felt so vigorous, so that in 1898 he and her accepted the offer of his nephew, Pastor Otto Nöldeke, to move to his large rectory in Mechtshausen. For Busch it was a retreat to old age. Wilhelm Busch read biographies, novels and short stories in German, English and French. He organized his works, wrote letters and poems. Most of the poems in the Schein and Sein (75 poems) and Last but not least collections were written in 1899. The years that followed were uneventful.

At the beginning of January 1908 he got a sore throat, and the doctor also diagnosed a weak heart. On the night of January 8th to 9th, 1908, Busch slept so restlessly that only camphor and a few drops of morphine gave him rest for a few hours. Before the doctor came, whom Otto Nöldeke called in the morning hours, Wilhelm Busch had died.

Poetry, writing, drawing

The creative periods

Busch's biographer Joseph Kraus divides Wilhelm Busch's work into three creative periods. However, he points out that this is a simplification, since in each of these periods there are also works that, by their nature, fall into a later or earlier period. Busch's fixation on forms of German petty-bourgeois life is common to all three creative periods. His peasant figures are people devoid of any sensitivity, and his last prose sketch shows village life in unsentimental and drastic form.

The years 1858 to 1865 are the years in which Wilhelm Busch worked primarily for the Fliegende Blätter and the Munich Bilderbogen . The creative period from 1866 to 1884 is mainly characterized by the great picture stories like the pious Helene . Busch's picture stories are the opposite of the representational culture that shaped the early days . They are résumés in descending order like that of the painter Klecksel , who begins as a hopeful son of a muse and ends as a mold host. Other stories are about children and animals who do not promise anything good, or they are farces that ridicule what seems big and important to itself. The early picture stories apparently follow the scheme of the children's books of classical Enlightenment pedagogy, of which Heinrich Hoffmann's Struwwelpeter is one of the best-known examples . This children's literature aimed to demonstrate to children the "devastating consequences of evil behavior". The pedagogical quintessence of Busch's picture stories, however, is often nothing more than an empty form or a philistine banality and reduces the moral application to absurdity. Wilhelm Busch did not attach any artistic value to the picture stories that made him a wealthy man: “I see my things for what they are, as Nuremberg trinkets , as whistling whistles , their value not in their artistic content but in their demand of the public is to be sought… ”he wrote in a letter to Heinrich Richter.

From 1885 until 1908, the year of his death, Wilhelm Busch's work was dominated by prose and poetry. The butterfly , a prose text published in 1895, is commonly understood as an autobiographical accountability report. Peter's enchantment by the witch Lucinde, whose slave he calls himself, could be an allusion to Johanna Keßler. And like Peter, Wilhelm Busch is also returning to the place of birth. It corresponds to the pattern of the romantic travel narrative, as established by Ludwig Tieck with Franz Sternbald's wanderings , and Wilhelm Busch plays virtuously with the traditional forms, motifs, images and topoi of this narrative form.

technology

The publisher Kaspar Braun , who commissioned Wilhelm Busch with the first illustrations, founded the first workshop in Germany that worked with wood engraving when he was young . This method of high-pressure process was towards the end of the 18th century by the British graphic artist Thomas Bewick been developed and was in the course of the 19th century the most widely used reproductive technology for illustrations . Wilhelm Busch always emphasized that he first made the drawings and then the verses for them. Preserved preliminary drawings show line notes, picture ideas, movement and physiognomy studies close together. Busch then transferred the preliminary drawing with the help of a pencil onto primed boards of end grain or heartwood made from hardwood . The work was difficult because not only the quality of your own transmission capacity influenced the result, but also the quality of the wooden printing block . Each scene in the picture story corresponded to a labeled boxwood stick. Everything that was to remain white on the later print was cut out of the plate by skilled workers with graver. The wood engraving allows a finer differentiation than the woodcut , and the possible tonal values almost approach that of gravure printing processes such as copper engraving . However, the implementation by the wood engraver was not always adequate for the preliminary drawing, and Wilhelm Busch had individual plates reworked or even made from scratch. The graphic technique of the wood engraving did not allow fine lines for all its possibilities. This is the reason why, especially in the picture stories up to the mid-1870s, the contours come to the fore in Busch's drawings, which gives the Busch figures a specific characteristic.

From the mid-1870s, Wilhelm Busch's drawings were printed using zincography . With this technique, there was no longer any risk of a wood engraver changing the character of his drawings. The originals were photographed and transferred to a photosensitive zinc plate. This process still required a clear ink stroke, but it was much faster, and the picture stories, beginning with Mr. and Mrs. Knopp, have more of the character of a free pen drawing.

language

Wilhelm Busch's drawings are enhanced in their effect by the accurate verses. Characteristic for the picture story are humorous surprises and linguistic boldness, e.g. B. rhymes that use hyphenation in an unexpected way, such as the well-known “Everyone knows what kind of a cockchafer / beetle such a bird is.” In addition, there are ironic distortions, mockery of romantic style elements, exaggeration and ambiguities. Accordingly, a number of humorous poets refer to Wilhelm Busch as a spiritual ancestor or at least a relative. This applies to Erich Kästner , Kurt Tucholsky , Joachim Ringelnatz , Christian Morgenstern , Eugen Roth and Heinz Erhardt . The contrast between the comical drawing and the apparently serious accompanying text, which is so typical of Busch's later picture stories, can already be found in Max and Moritz . So the maudlin grandeur of the widow Bolte is out of proportion to the actual occasion, the loss of her chickens:

- You tears flow from your eyes!

- All of my hope, all of my longing

- Most beautiful dream of my life

- Hangs on that apple tree

Many of the two-line lines that have become common language have the impression of a weighty wisdom saying, but on closer inspection turn out to be pseudo- truth, pseudo-morality or even just truism . Numerous onomatopoeia are also characteristic of his work . "Schnupdiwup", Max and Moritz kidnap the roasted chickens with a fishing rod through the fireplace, "Ritzeratze" they saw in the "bridge a gap", "Rickeracke! Backpack! The mill goes with a crack ”, and“ Klingelings ”, tomcat Munzel tears the chandelier from the ceiling in the pious Helene . Wilhelm Busch is equally resourceful in assigning proper names, which often aptly characterize his characters. “Studiosus Döppe” would surprise the reader as an intellectual greatness; Figures like the “Sauerbrots” do not suggest any cheerful natures and “Förster Knarrtje” no elegant salon lion.

The greater part of the picture stories are composed in four -part trochaes:

- Max and Mor itz, the se in the

- Moch th him because rum is not lei to.

An overweighting of the stressed syllables increases the comedy of the verse. In addition, there are dactyls in which a stressed syllable is followed by two unstressed ones. They can be found, for example, in Plisch and Plum and underline the lecturing, solemn address that teacher Bokelmann gives his students, or build tension in the sour bread chapter of a bachelor’s adventure by alternating trochaes and dactyls. The fact that Busch often matches the form and content of his poetry is also shown in Fipps, the monkey , where the epic hexameter is chosen for a conversation about the wisdom of creation, which culminates in human dignity .

In his picture stories as well as in his poems, Wilhelm Busch occasionally used fables familiar to the reader, some of which he robbed of their morality, in order to make use of the comical situations and constellations that developed from the mythical events, and sometimes he made them the medium of a completely different truth. Here, too, Busch's pessimistic world and human view comes into play. While traditional fables convey the value of a practical philosophy that distinguishes between good and bad, in Busch's worldview, good and bad behavior seamlessly merge.

humor

Wilhelm Busch's humor is difficult to describe and often goes as far as caricaturistic , grotesque and even macabre . He expresses himself not only in the verses to the pictures of his picture stories, but also in his poems and in the unpublished introductory texts of his picture stories. The main effect is apparently based on a combination of the known, "unfortunately all too true" etc. with the unexpected, surprising and a certain irony (also self-irony) and cruelty (see below). For example, Wilhelm Busch was unmarried all his life and, as a follower of Schopenhauer's "pessimism", was a subtle connoisseur of philosophy, which he, however, turned into popular and humorous. It is therefore not unexpected that he writes in the introduction to The Adventures of a Bachelor :

- Socrates, the old man ,

- spoke very often in great worry:

- "Oh how much is hidden ,

- what you still don't know . "

- And so it is. - In the meantime

- one must not forget one thing:

- One you know but here below ,

- namely, when one is dissatisfied

- This is also Tobias Knopp ,

-

and he is angry about it .

(Before the last two lines, a picture of the "angry" Knopp.)

For the grotesque of Busch's humor, the following text:

- At the thought

- so to divorce

- in an unweeping grave

- he pulls off a tear .

- It lies where he sat

-

appropriate to his pain.

(In front of the last two lines a picture with an oversized tear in front of a normal-sized bench.)

An example of the subtle cruelty of his humor - whereby it is not about physical, but psychological cruelty - is the poem, masterfully interpreted by Erich Ponto - the interpretation is archived by Deutsche Grammophon - "The first old aunt spoke ...". In this poem, three old aunts discuss a birthday present for "Sophiechen". The second old aunt suggests a pea-green dress because Sophie cannot (!) Stand that. The poem continues:

- The third aunt was right ,

- “Yes,” she said, “with yellow tendrils .

- I know she doesn't get angry

- and also have to say thank you. "

But the poem She was a flower also testifies to the subtle cruelty:

- She was a pretty and fine flower,

- Bloomed brightly in the sunshine.

- He was a young butterfly

- Who hung blissfully on the flower.

- Often a bee would come with a growl

- And nibbles and purrs around there.

- Often a beetle crawled kribbelkrab

- Up and down the pretty little flower.

- Oh God, like that to the butterfly

- So painfully went through the soul.

- But what horrifies him most

- The very worst came last.

- An old donkey ate the whole thing

- So much loved plant by him.

Corporal punishment and other cruelty

Most of Wilhelm Busch's picture stories are beaten, tortured, injured and beaten: Pointed pencils pierce painters' models , housewives fall into kitchen knives, thieves are impaled by umbrellas, tailors guillotine their tormentors with scissors, rascals are ground to grain in mills, drunks are charred blackish something, and cats, dogs, monkeys lose their extremities . Impal injuries are common. Today Wilhelm Busch is classified by some educators and psychologists as a disguised sadist . Eva Weissweiler also points out that Wilhelm Busch's tail is so often burned, torn off, pinched, stretched or eaten that it can hardly be assessed as a coincidence. She is of the opinion that this aggression is not directed against animals, but against the phallic symbolism of the animal tail and is to be seen against the background of Wilhelm Busch's underdeveloped sexual life. Drastic texts and images were, however, quite characteristic of caricatures of the time, and neither publishers nor audiences nor censors found anything remarkable about them. The theme and motifs of Busch's early picture stories, in particular, often come from the trivial literature of the 18th and 19th centuries, and Wilhelm Busch has often even toned down the gruesome outcome of his models.

The situation is similar with corporal punishment , which in the 19th century (and beyond) was one of the common and widely accepted means of education . Wilhelm Busch caricatured an almost sexual pleasure in this punishment with Master Druff in the adventure of a bachelor and with teacher Bokelmann in Plisch and Plum . Beatings and humiliations as the basic structure of a pedagogy are also described in the later work, so that the Busch biographer Gudrun Schury describes these educational tools as a theme of life for Busch. Even in the group of 100 poems poetry collection Finally from 1904 states:

- The stick whizzes, the rod buzzes.

- You mustn't show what you are

- What a shame, O man, that you are good

- Basically so repugnant.

Although there is a note in Busch's estate “beaten through childhood”, there is no indication that Wilhelm Busch referred this short note to himself. His father and his uncle can not refer, as Bush mentioned only a beating he had received from his father, and his uncle George Little punished the nephew only once with blows after this the village idiot , the whistle with Kuhhaaren had stuffed. Instead of the usual rattan cane , Georg Kleine used a dried dahlia stalk , which made the punishment more symbolic. Eva Weissweiler points out, however, that Busch attended the Wiedensahler village school for three years and was very likely not only a witness of flogging, but was probably also physically punished himself. In The Adventure of a Bachelor , Wilhelm Busch outlines a form of nonviolent reform pedagogy that fails just as much as the beatings shown in the following scene. The beating scenes ultimately express Wilhelm Busch's pessimistic image of man, which is rooted in the Protestant ethics of the 19th century , which was influenced by Augustine : Man is by nature evil, he can never master his vices. Civilization is the goal of education, but it can only superficially cover up what is instinctual in people. Meekness only leads to a continuation of his misdeeds and punishment is necessary, even if this leads to incorrigible rascals, trained puppets or in extreme cases to dead children. It remains to be seen whether Busch also had an outwardly directed request for punishment .

Accusation of anti-Semitism

The so-called Gründerkrach of 1873 led to growing criticism of high finance , combined with the spread and radicalization of modern anti-Semitism , which in the 1880s became a strong undercurrent in the opinions and attitudes of Germans. Anti-Semitic agitators like Theodor Fritsch made a distinction between "grabbing" finance capital and "creating" production capital , between the "good", "down-to-earth" "German" manufacturers and the "grabbing", "greedy", "bloodsucking" "Jewish" financial capitalists who were called " Plutocrats " and " Usurers " were designated.

Wilhelm Busch is also accused of having used these anti-Semitic clichés. Two places are usually used as evidence for this. In the pious Helene it says:

- And the Jew with a crooked heel,

- Crooked nose and crooked pants

- Meanders to the high stock exchange

- Corrupted and soulless.

The poet and Busch admirer Robert Gernhardt points out that this passage, read in context , does not reflect Busch's own point of view, but caricatures that of the villagers under whom Helene lives. Because in the following the liberal, anti-clerical and the alcohol not averse Busch paints further alleged dangers of city life in ironic black colors:

- I want to be silent about restaurants

- Where the wicked splurge at night

- Where in the circle of liberals

- One hates the Holy Father .

Just as ironically, Busch caricatures the rural counter-image as a false idyll:

- Come to the country where gentle sheep

- And the pious lambs are.

The second, even clearer caricature of "the Jew" can be found in the story Plisch and Plum :

- Short the pants, long the skirt

- Bent nose and stick

- Eyes black and soul gray,

- Hat to the back, expression smart -

- That's Schmulchen Schiefelbeiner

- (One of us is more beautiful!)

According to the Busch biographer Joseph Kraus, these verses could also be in an anti-Semitic propaganda sheet. The biographer Eva Weissweiler sees them as one of the most memorable and ugliest portraits of an Eastern Jew that the German satirical landscape has to offer.

But here, too, the context, in particular the ironic last verse of the quoted passage - “Our one is more beautiful!” - shows that Busch by no means viewed non-Jews as the nobler kind of person. Robert Gernhardt points out how extremely rare caricatures of Jews can be found in Busch's work. In total there is only one other drawing in Fliegende Blätter from 1860, which also illustrates the text of another author. In Gernhardt's view, Wilhelm Busch's Jewish figures are nothing more than stereotypes like the limited Bavarian farmer or the Prussian tourist .

Joseph Kraus shares this view: Wilhelm Busch had turned against cunning businessmen in general and used caricatures of Jews, but not only of them, in some picture stories. This can be seen in a two-line from the picture story The Hair Bags . After that are profit-addicted fellow men

- Mainly Jews, women, Christians,

- Who outsmart you terribly.

Erik de Smedt speaks of a "certain ambivalent attitude towards the Jews by Busch". In Edward's dream, for example, he puts the sentence in the mouth of the title character: “The business is in bloom, and so is the Israelite. He's as smart as anything, and where there's something to be earned, he doesn't leave anything out ... ”By contrast, the preceding text passage about the house and tenants of an“ anti-Semitic building contractor ” speaks of all kinds of vices , e.g. B. of attempted murder, envy, hatred, fraud and marital disputes. Busch's prejudices are shown where Eduard encounters the signs of the zodiac :

- Not far from there, in his shop, sat the cunning, crooked-nosed “Aquarius” - there are Jews everywhere! - and adjusted the "scales" in his favor .

Joseph Kraus believes that Busch - like most of his contemporaries - perceived Jews as foreign bodies and shared some of their anti-Semitic thought patterns. But this did not rule out close friendships with Jews, for example with the conductor Hermann Levi .

The picture stories as anticipation of the modern comic

Busch's work contributed to the development of the comic , Andreas C. Knigge describes him as the first virtuoso of picture narration. From the second half of the 20th century, his work therefore increasingly earned him the honorable nickname “grandfather of comics” or “forefather of comics”.

Even his early picture stories differ from those of his colleagues who also worked for Kaspar Braun. His pictures show an increasing concentration on the main characters, are more economical in the interior drawing and less fragmented in the ambience. The punch line develops from a dramaturgical understanding of the entire story. All picture stories follow a course of action that begins with a description of the circumstances from which the conflict arises, then increases the conflict and finally brings it to its resolution. The plot is broken down into individual situations like in a film. In this way, Busch gives the impression of movement and action, sometimes reinforced by a change of perspective. According to Gert Ueding, the representation of movement that Busch succeeds in despite the limitation of the medium has so far remained unmatched.

One of Busch's most ingenious and revolutionary picture stories is Der Virtuos , the story of a pianist , published in 1865 , who gives an enthusiastic listener a private concert for the New Year. This satire on self-portrayal artist attitude and their exaggerated admiration deviates from the scheme of Busch's other picture stories because the individual scenes are not commented on with bound texts, but only terms from musical terminology such as Introduzione , Maestoso or Fortissimo vivacissimo are used. The scenes increase in pace, with every part of the body and every corner of clothing being included in this increase. Finally, the penultimate scenes become a simultaneous display of several phases of movement of the pianist, and the notes dissolve into notes dancing over the grand piano. Fine artists were inspired by this picture story well into the 20th century. August Macke even stated in a letter to his gallery owner Herwarth Walden that he thought the term futurism for the avant-garde art movement that emerged in Italy at the beginning of the 20th century to be a mistake, since Wilhelm Busch was already a futurist who insisted on time and movement Image banned.

Individual scenes in the pictures from the Jobsiade , published in 1872, are similarly forward-looking . At Jobs' theological exam, twelve clergymen in white wigs sit across from him. Your examinee answers her questions, which are by no means difficult, so stupidly that every answer triggers a synchronous shake of the head of the examiners. The wigs start to move indignantly, and the scene becomes a movement study that is reminiscent of Eadweard Muybridge 's phased photographs . Muybridge had begun his movement studies in 1872, but did not publish them until 1893, so that this flowing transition from drawing to cinematography is also a pioneering artistic achievement by Busch.

Moritziaden

The greatest long-term success, both internationally and in the German-speaking world, was granted to Max and Moritz : In the year of Busch's death, there were already English, Danish, Hebrew, Japanese, Latin, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Hungarian, Swedish and Walloon translations of his history. However, there were also countries in which people resisted the “elaborate” for a long time. The Styrian school authorities forbade the sale of Max and Moritz to young people under the age of eighteen in 1929 . However, in 1997 there were at least 281 translations into dialects and languages, including languages such as South Jutish .

Very early there were so-called Moritziaden , that is, picture stories whose plot and narrative style were very closely based on Busch's original. Some, like the Tootle and Bootle story published in England in 1896 , took so many literal translations from the original that it was actually a kind of pirated print . On the other hand, the Katzenjammer Kids of the native Holsteiner Rudolph Dirks , which appeared every Saturday in a supplement of the New York Journal from 1897 onwards , are considered to be a real new creation, whose role models are Max and Moritz . They were created at the suggestion of the publisher William Randolph Hearst with the explicit desire to invent a pair of siblings that followed the basic pattern of Max and Moritz . The Katzenjammer Kids are considered one of the oldest comic strips and are still being continued.

The German-speaking area has a particularly rich tradition of Moritziaden: that extends from Lies and Lene; the sisters of Max and Moritz from 1896 to Schlumperfritz and Schlamperfranz (1922), Sigismund and Waldemar, the Max and Moritz twin pair (1932) to Mac and Mufti (1987). While in the original Max and Moritz lay bare the bravery and honesty of their opponents, who enforce their authority by force, as a hypocritical facade, the Moritziades often merely reflect the spirit of the respective epoch. In both World War I and World War II, there were Moritziaden telling the fate of the protagonists in the trenches, the winter relief organization collected money with their badge, and in 1958 the CDU fought for votes in North Rhine-Westphalia with the help of the Max and Moritz figures , In the same year the GDR satirical magazine Eulenspiegel caricatured illegal work , and in 1969 Wilhelm Busch's heroes were involved in the student movement.

painting

Wilhelm Busch seems to have never completely lost the self-doubt about his painting abilities that befell him when he first dealt with the old Dutch painters in Antwerp. He felt few of his paintings were finished. He often piled them up in the corners of his studio while still damp, so that they glued together inexorably. If the stacks of pictures got too high, he burned them in the garden. Only a few of the surviving images are dated, so it is difficult to put them into a historical order. His doubts about his painting abilities are also expressed in the choice of materials. In most of his works, his painting grounds are chosen carelessly. Occasionally it is uneven cardboard or spruce boards that are only poorly smoothed and secured with only one burr ledge. An exception is a portrait of his sponsor Johanna Keßler, whose painting base is canvas and which, at 63 by 53 centimeters, is one of Wilhelm Busch's largest paintings. Most of his paintings are much smaller in size. Even the landscapes are miniatures, the reproductions of which in illustrated books are often larger than the original. Since Wilhelm Busch used not only cheap painting grounds, but also cheap colors, many of his pictures have now darkened considerably and thus have an almost monochrome effect.

Many of his pictures show a fixation on rural life in Wiedensahl or Lüthorst. It depicts motifs such as polluted willows, cottages in the cornfield, cowherds, autumn landscapes, meadows with streams. The so-called red jacket pictures are striking . Among the almost 1,000 paintings and sketches by Wilhelm Busch, there are around 280 on which a red jacket can be discovered. It is usually a tiny figure seen from behind, dressed in muted colors but wearing a bright red jacket. The portraits usually show typical village characters.

In addition to portraits of the Keßler family, an exception is a series of portraits by Lina Weißenborn from the mid-1870s. The 10-year-old girl was the daughter of one of the Jewish families that had lived in Lüthorst for generations. They show a serious girl with dark oriental features who hardly seems to notice the painter. Some critics consider her portraits to be among the most poignant portraits of Wilhelm Busch, which go far beyond the typical of his other portraits.

The influence of Dutch painting is unmistakable in Busch's work. " Neck thins and shrinks ... but a little neck", wrote Paul Klee after visiting a Wilhelm Busch memorial exhibition in 1908. Adriaen Brouwer , who exclusively depicts scenes from farm and inn life , had a particular influence on Wilhelm Busch's painterly work , Peasant dances, card players, smokers, drinkers and thugs. Busch avoided dealing with influential German painters of his time such as Adolf Menzel , Arnold Böcklin , Wilhelm Leibl or Anselm Feuerbach . The discovery of light in early Impressionism , new colors such as aniline yellow or the use of photographs as an aid were not taken into account in his painting. His landscapes from the mid-1880s, however, show the same rough brushstroke that was characteristic of pictures by the young Franz von Lenbach. Although he was friends with several painters from the Munich School and because of these contacts he would have been able to exhibit his pictures without any problems, he never took this opportunity to present his painterly work. It was only towards the end of his life that he exhibited a single picture in public.

Works (selection)

Publications by year of publication

Picture stories that were not published as an independent work, but appeared, for example, in the Fliegende Blätter are only listed insofar as they are of interest to Wilhelm Busch's artistic development.

- 1859 The little honey thieves

- 1860 Loyalty to love and cruelty. Romantic opera in 3 acts by Motzhoven. (Munich, February 8, 1860)

- 1862 The cousin visiting. Comic opera in 1 act. (Music: Georg Kremplsetzer) - first performed in 1863

- 1863 Natural history alphabet in the Munich picture sheet

- 1864 picture antics (with the individual stories Cat and Mouse , Hansel and Gretel , Krischan with the Piepe and The Ice Peter )

- 1864 Diogenes and the Bad Boys of Corinth

- 1864 Eginhard and Emma

- 1865 The virtuoso

- 1865 Max and Moritz ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- 1866 gnaws and purrs

- 1867 Hans Huckebein, the unlucky fellow

- 1868 Schnaken and Purren, Part II

- 1869 Schnurrdiburr or The Bees

- 1870 Saint Anthony of Padua

- 1872 Schnaken and Purren, Part III

- 1872 The pious Helene

- 1872 Pictures from the Jobsiade

- 1872 Father Filucius

- 1873 The birthday or the particularists

- 1874 Dideldum!

- 1874 Critique of the Heart

- 1875 adventure of a bachelor

- 1876 Mr. and Mrs. Knopp

- 1877 Julchen

- 1878 The hair bag

- 1879 Fipps the monkey

- 1881 Small storks for eyes and ears

- 1881 the fox. The Dragons. - Two fun things

- 1882 Plisch and Plum

- 1883 Balduin Bählamm, the prevented poet

- 1884 painter Klecksel

- 1886 As for me

- 1891 Edward's dream

- 1893 From me about me

- 1895 The butterfly

- 1904 Last but not least

- 1908 Hernach (posthumously, printed as autograph )

- 1909 appearance and being (posthumous)

- 1910 Ut ôler Welt (posthumous)

- 1923 Wilhelm Busch Collected Works

- 2010 (lost since 1863 and only rediscovered in 2008) Der Kuchenteig with an essay by Andreas Platthaus , (= Insel-Bücherei , Volume 1325), Insel, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-458-19325-8 .

Selection of publications

Print editions and digitized versions

- Wilhelm Busch, album , selected and compiled by Anneliese Kocialek . The children's book publisher, Berlin 1978; ISBN 3-358-01000-7 (first edition 1959).

- Rolf Hochhuth (Ed.): All works and a selection of the sketches and paintings in two volumes. Volume 1: And the moral of the story. Volume 2: What is popular is also allowed. Bertelsmann, Gütersloh 1959; New edition Munich 1982, ISBN 3-570-03004-0 .

- Aphorisms and rhymes. In: Rolf Hochhuth (Ed.): Complete works and a selection of the sketches and paintings in two volumes. Volume 2: What is popular is also allowed. Bertelsmann, Gütersloh 1959; New edition Munich 1982, ISBN 3-570-03004-0 , pp. 865-885.

- Otto Nöldeke (ed.): Wilhelm Busch, Complete Works . Eight volumes. Braun & Schneider, Munich 1943, Volume 1: DNB 365409219 .

- Hugo Werner (Ed.): Wilhelm Busch. Complete works in six volumes. Weltbild, Augsburg 1994, DNB 942761960 .

- Doctors, pharmacists. Patients with Wilhelm Busch . collected and presented by Ulrich Gehre , Verlag SCHNELL, Warendorf 2007, ISBN 978-3-87716-877-6 .

- Poems and picture stories (= two handbooks ), Diogenes, Zurich 2007, ISBN 978-3-257-06560-2 .

- Then the pig grunted, the Englein sangen / Wilhelm Busch , selected and with an essay by Robert Gernhardt , Frankfurt am Main: Eichborn 2000, series Die Other Bibliothek , ISBN 978-3-8218-4185-4

- Herwig Guratzsch, Hans Joachim Neyer (Hrsg.): The picture stories / Wilhelm Busch. , [first] historical-critical complete edition, commissioned by the Wilhelm Busch Society . 3 volumes, Schlütersche , Hannover 2002, ISBN 3-87706-650-X (2nd, revised edition 2007, ISBN 978-3-89993-806-7 ).

- Collected works (= digital library , (CD-ROM), volume 74). Directmedia, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-89853-474-X .

- Gudrun Schury (Ed.): Hundred poems . Structure, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-351-03217-3 .

- Wilhelm Busch: Works. Historical-critical complete edition (edited and edited by Friedrich Bohne, 4 volumes), Standard, Hamburg 1959 DNB 860192962 (volume 1).

-

Wilhelm-Busch-Gesellschaft e. V. Hannover (Hrsg.): Complete letters. Annotated edition in 2 volumes / Wilhelm Busch. commented by Friedrich Bohne with the assistance of Paul Meskemper and Ingrid Haberland [this reprint is based on an original from the limited edition from 1968/69]. Schlueter , Hannover 1982, ISBN 3-87706-188-5 .

- Volume 1: Letters 1841 to 1892 .

- Volume 2: Letters 1893 to 1908 .

Settings and readings

- The pious Helene - a Wilhelm Busch inhalation in 17 puffs. Opera by Edward Rushton , libretto by Dagny Gioulami. Based on the picture story of the same name by Wilhelm Busch. World premiere: February 11, 2007, State Opera Hanover

- Max and Moritz, Hans Huckebein and Die pious Helene. Complete reading (= audio CD, approx. 57 min., Speaker Rufus Beck ), DHV - Der Hörverlag, Munich 2005, ISBN 978-3-89584-372-3 .

- Wilhelm Busch - Entertaining and inappropriate things for children. Verlag Audionauten 2007, ISBN 978-3-86604-530-9 . Eight settings from Hans Huckebein to Der Hahnenkampf with the duo piano words: Helmut Thiele (narrator) and Bernd-Christian Schulze (piano)

- Max and Moritz - Cantata in seven strings for mixed choir and piano (1998) - Music: Siegfried Strohbach , Verlag Edition Ferrimontana

- The ballad by Rieke and Nischke - based on a text by Wilhelm Busch for mixed choir a cappella (1981) - Music: Siegfried Strohbach, Verlag Edition Ferrimontana

- Six cheerful choir songs based on texts by Wilhelm Busch - for mixed choir a cappella (1945) - Music: Siegfried Strohbach, Verlag Edition Ferrimontana

Memorials and memorials

Appreciations

Wilhelm Busch's 70th birthday was an occasion to pay tribute to the humorous poet. While Wilhelm Busch was spending his birthday with his nephew in Hattorf am Harz to avoid the hustle and bustle, over a thousand congratulatory letters from all over the world arrived in Mechtshausen. Wilhelm II sent a congratulatory telegram in which he praised him as a poet and draftsman whose "delicious creations full of genuine humor will live forever in the German people". In the Austrian Imperial Council , the Pan-German Unification faction enforced a lifting of the ban on St. Anthony of Padua that had been in force in Austria until then . The Braun & Schneider publishing house , which owned the rights to Max and Moritz , transferred a gift of 20,000 Reichsmarks (around EUR 200,000 based on today's purchasing power), which Wilhelm Busch donated to two hospitals in Hanover.

Since then, round deathdays and birthdays have repeatedly been an occasion to commemorate Wilhelm Busch. In 1986, ZDF showed a TV film by Hartmut Griesmayr about Wilhelm Busch under the title “If you are lonely, you have it good / Because nobody is there to do anything to you” . On the occasion of Busch's 175th birthday in 2007, not only a number of new publications appeared. The German post brought new youth brand with designs from Busch figure Hans Hucke leg and the Federal Republic of Germany, a 10-euro silver coin with his image out. The city of Hanover declared 2007 the "Wilhelm Busch Year", during which advertising pillars with large-format drawings by the artist were exhibited in the city center for a few months .

Wilhelm Busch Society, Wilhelm Busch Prize

The Wilhelm Busch Society, which has existed since 1930, has set itself the goal of “collecting Wilhelm Busch's work, processing it scientifically and making it accessible to the public”. The company promotes the development of the artistic fields of " caricature " and "critical graphics " into a recognized branch of the visual arts . It is also the sponsor of the German Museum for Caricature and the Art of Drawing Wilhelm Busch , which is located on the upper floor of the Georgenpalais in Hanover .

The Wilhelm Busch Prize is awarded every two years for satirical and humorous poetry .

Memorials

There are memorials and museums at, among other places, Busch's former residence and residence:

- Wiedensahl : Wilhelm Busch birth house and Wilhelm Busch residence (1872–1879) in the former rectory

- Hameln : Wilhelm Busch House

- Ebergötzen : Wilhelm-Busch-Mühle (1841–1846)

- Lüthorst : Wilhelm Busch room in the former residence (1846–1897)

- Mechtshausen : Wilhelm-Busch-Haus, museum in the former rectory, where he lived during the last years of his life (1898–1908)

- Seesen : Life-size sculpture by Wilhelm Busch in the street (Mechtshausen is a district of Seesen)

- Hattorf am Harz : Wilhelm Busch Memorial

- Hanover: Wilhelm Busch Museum

- Hanover, city sign on the former house while studying (formerly: Schmiedestraße 33, today Schmiedestraße 18)

Wilhelm Busch sculpture in Seesen

literature

- Wilhelm Busch: From me about me. [1893]. In: Rolf Hochhuth (Ed.): Wilhelm Busch, Complete Works and a selection of the sketches and paintings in two volumes. Volume 2: What is popular is also allowed. Bertelsmann, Gütersloh 1959; Reprint, pp. 8–31.

- Stations of his life in pictures and occasional poetry. In: Rolf Hochhuth (Ed.): Wilhelm Busch, Complete Works and a selection of the sketches and paintings in two volumes. Volume 2 Whatever is popular is also allowed. Bertelsmann, Gütersloh 1959, pp. 886-1045.

- Michaela Diers: Wilhelm Busch. Life and work. Original edition. dtv 34452, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-423-34452-4 .

- Maria Döring: Humor and pessimism in Wilhelm Busch. Munich 1948, DNB 481761055 (Dissertation University of Munich, Philosophical Faculty, June 1, 1948, 100 pages).

- Armin Peter Faust : Iconographic Studies on Wilhelm Busch's Graphics (= Art History , Volume 17), Lit, Münster / Hamburg 1993, ISBN 3-89473-388-8 (Dissertation Saarbrücken University 1992, II, 372 pages, illustrations, 21 cm).

- Ulrich Gehre : Doctors, pharmacists, patients with Wilhelm Busch , Verlag Schnell, Warendorf 2007, ISBN 978-3-87716-877-6

- Herbert Günther : The hide-and-seek, the life story of Wilhelm Busch. Union Verlag, Fellbach 1991, ISBN 3-407-80894-1 .

- Peter Haage: Wilhelm Busch. A wise life. Fischer-Taschenbuch 5637, Frankfurt am Main 1984, ISBN 3-596-25637-2 (first edition: Meyster, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-7057-6003-3 ).

- Karl-Heinz Hense: Humourist against his will - The life of Wilhelm Busch . In: Mut - Forum for Culture, Politics and History No. 492. Asendorf August 2008. pp. 86–95.

- Clemens Heydenreich: "... and so good!" Wilhelm Busch's fairy tale "The Butterfly" as a rubble field of the "good-for-nothing" romance. In: Aurora. Yearbook of the Eichendorff Society. 68/69 2010, ISBN 978-3-484-33066-5 , pp. 67-78.

- Walter Jens: Kindlers New Literature Lexicon (= study edition Volume 3 of 21). Munich, ISBN 3-463-43200-5 , p. 416.

- Wolfgang Kayser : Wilhelm Busch's grotesque humor. Vandenhoeck & Rupprecht, Göttingen 1958. (Short lecture, (online) available)

- Joseph Kraus, Kurt Rusenberg (ed.): Wilhelm Busch. With personal testimonials and picture documents (= rororo picture monographs No. 50163). 17th edition. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, ISBN 978-3-499-50163-0 (first edition 1970).

- Dieter P. Lotze: Wilhelm Busch. Life and work. Belser, Stuttgart a. a. 1982, ISBN 3-7630-1915-4 .

- Ulrich Mihr: Wilhelm Busch: The Protestant who laughs anyway: philosophical Protestantism as the basis of literary work, Narr, Tübingen 1983, ISBN 3-87808-920-1 (dissertation University of Tübingen 1982, 199 pages table of contents ).

- Fritz Novotny: Busch, Wilhelm. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 3, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1957, ISBN 3-428-00184-2 , pp. 65-67 ( digitized version ).

- Frank Pietzcker: Symbol and Reality in Wilhelm Busch's Work. The hidden statements of his picture stories (= European university publications, series 1, German language and literature , volume 1832), Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2002, ISBN 3-631-39313-X .

- Heiko Postma : "I should laugh if the world was going to end ..." About the poet, thought and drawing artist Wilhelm Busch. jmb, Hannover 2009, ISBN 978-3-940970-01-5 .