humor

Humor is a person's ability to face the inadequacy of the world and people, everyday difficulties and mishaps with cheerful serenity . This narrower view is expressed in the proverbial phrase humor is when you laugh anyway , which is ascribed to the German writer Otto Julius Bierbaum (1865–1910). In a further opinion but also those people are as humorous referred, bring the other people laugh or even conspicuously often funny aspects of a situation to express.

etymology

The word humor is borrowed from Latin humor in the meaning of moisture : According to the temperament theory developed by Galen , the mental mood of the person was dependent on the juices effective in the body that produce the choleric , melancholic , phlegmatic or sanguine temperament. The development of the meaning of the word humor, which is customary today and whose final emphasis is aligned with the French humeur , comes from English. humor . This term included in the 17./18. Century a special genre that wanted to portray comic situations in playful cheerfulness, whereby the emergence of the English comedy had already started in the 16th century.

Theories

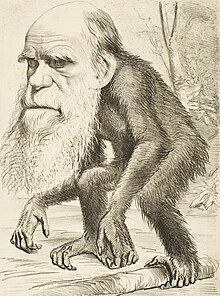

There are theoretical approaches to explain humor from various scientific, psychological and social perspectives, but a “unified theory of humor” has not yet been developed. The great variety of laughter, its aims, processes and occasions probably play a role here. After all, there is now consensus that laughter as a cultural phenomenon is tied to a specific historical, social and personal constellation. For historically early forms, however, there are still more open questions than sources. For example, it is controversial whether humans alone have the ability to use humor ("Man: the laughing monkey"), or whether other living beings also have this ability (see below).

Even field research in ethnology has so far not been able to integrate its many observations: what one laughs about, who triggers the laugh and how, what effect a laugh has in a social context - the answers to these questions are still very different. A particular difficulty is that the laughter of other cultures could often only be observed in the contact situation with ethnologists: Other ethnic groups laughed at the behavior of the ethnologists, which was astonishing to them. So the origin and behavior of the researchers occasionally influenced the actions and reactions of the individuals they observed during their observations.

Essentially three main theories are known which try to grasp the core of a humorous moment and which have existed for centuries or even millennia: superiority theory, incongruence theory and discharge theory.

The superiority theory goes back to Aristotle . It is said that we laugh in those situations in which we feel superior to others, e.g. B. in the event of an accident. As things stand today, this theory only covers part of all humorous situations.

A main proponent of the incongruence theory was u. a. Cicero . This means that we always laugh when a surprising change to another, usually more trivial point of view takes place. A given situation is therefore assessed from two different perspectives, whereby one of these perspectives is usually a simpler or inadequate perspective. It is not difficult to find examples of this, especially puns.

The so-called discharge theory goes back to Sigmund Freud . According to Freud, humor serves to dissolve psychological tensions or inhibitions. A socio-cultural background is usually ascribed to these inhibitions. In other words, according to Freud, humor serves to reveal (discharge) suppressed desires in a certain way.

A definition has recently been found which unifies the three theories, namely that our laughter is “an acoustic indication of an unnoticed relapse into simpler behavior patterns”. The evolutionary history and the relatively complicated connection to ticklish can also be shown in this way.

Function and structure

It is generally understood in the Germans humor when you are in a particular situation still laughing. This formulation is attributed to Otto Julius Bierbaum . If you take a closer look nevertheless , then humor combines weakness and strength in a peculiar way: A laugh is only humor if it occurs in a situation of danger or failure, is not directed against third parties and even the smallest hope mediated on overcoming the crisis.

The triggers for a humorous laugh are the mistakes that you have not yet made - despite others that you have already made . This artificial doubling of one's own weakness symbolically overcomes the threat of the situation. In this low level of resistance is the optimistic hint that the situation will not be surrendered without resistance. This symbolic anticipation conveys new hope for a solution in real life as well. In humor, a person makes himself more stupid than he is and thereby becomes stronger than he seems.

Humor is recognized by the construction of an apparently inappropriate, marginal point of view, or inadequate behavior in a situation of danger, failure, or defeat. The inappropriateness is deliberately staged linguistically or in behavior and the danger is played around in a flimsy way. Difficulty is presented as a luxury, the unpleasant as an achievement and a nonsensical meaning is constructed afterwards. Christopher Fry : "Humor is an escape from despair, a narrow escape into faith." Typical formulations for the humorous reinterpretation of an uncertain situation are: "At least we have ..." or: "At least better than ..." Examples:

- Madelaine tells her husband that her psychiatrist warned her about her paranoid moments. “In any case, I will never bore you,” she announces to Herzog. ( Saul Bellow : Duke )

- “'Lime juice is very healthy in this climate. It contains - well, I'm not exactly sure what vitamins it contains. ' He handed me a mug and I drank. 'Well, at least he's wet,' I said. "( Graham Greene , The Quiet American )

- An early example: 480 BC. Xerxes I threatens the Greeks at Thermopylae : "I have so many archers that their arrows will darken the sun!" According to tradition, King Leonidas of Sparta has the answer: "All the better - then we fight in the shade!"

In contrast to the devaluation of others in irony , ridicule or cynicism , Leonidas makes this humorous remark (also) about himself: He even dies before his warriors in that battle. The important thing is: Leonidas thinks as a person affected, not as a know-it-all. This humor and self-irony seem closely related, but perhaps differ in that humor is addressed to a larger audience. In contrast to other forms of laughter, humor creates community - irony, ridicule and cynicism, on the other hand, are forms of thought of deconstruction and social escalation, which only integrate through social struggles. “Better to lose a friend than a joke!” - this motto, which goes back to Quintilian , may mean a lot of laughter, but no humor.

As an example of the shift in perspective to an apparently inappropriate point of view, Freud mentions the remark of a delinquent who is led to the gallows on Monday and comments: "Well, the week has started well." (Der Humor, 1927) The humorous attitude towards oneself or others is based on, as Freud explains, "that the person of the humorist has removed the psychic accent from his ego and transferred it to his super-ego. This so-swollen super-ego can now the ego appears tiny, its interests minor ". Accordingly, "humor would be the contribution to the comedy through the mediation of the superego."

Differentiation of irony, ridicule, cynicism and wit

An understanding of humor as a way of thinking of the nonetheless proves itself in the demarcation to other forms of laughter. The external appearance of the presentation - whether printed, spoken, played or drawn - is completely unimportant. What is essential, however, is that other forms of laughter have a structure that is clearly distinguishable from humor in the narrower sense:

Irony is a way of thinking that enlarges the break between self-image and external image, between intentions and effects, between necessary and actual behavior. She always aims at someone other than the observer, confronts third parties with their unreached ideals or with a transparent re-evaluation of the factual. Distancing imitation and critical reinforcement are their principle: irony demonstrates the untenable side linguistically, pulls the inadequacy to light and makes exaggerations or understatements visible through symbolic continuation. In doing so, irony sometimes means the opposite of what is being said. Examples:

- Liesl Karlstadt : “I'm coming for the house!” Karl Valentin : “It's a little house.” Karlstadt: “House, little house, little house. Is it outside? "

- Sartre's grandfather, who was in love with his grandson, resented Sartre's early death at the age of only thirty-two: "In view of this suspicious departure, he wondered whether his son-in-law had ever existed ..." ( Jean-Paul Sartre , The Words )

- "To love his voice, the bassist never drank anything hotter than milk." ( James Joyce , Dubliner )

Self-irony , which is only listed here because of the similarity of words, is a form of processing the lack of size. In it the observer comments on himself, insofar as it is closely related to humor in the narrower sense. Perhaps self-irony is a kind of humor that limits the circle of those responsible to the observer. Examples:

- “I rule countless people, but I have to acknowledge that I am ruled by birds and thunderbolts,” says Caesar. ( Thornton Wilder , The Ides of March)

- The old man was a despot and "in his presence I acted as if he had made me out of a lump of clay by hand ..." ( John Cheever , The Swimmer)

- The children have just survived an assassination attempt and met their mysterious neighbor and savior for the first time: "On the way home I said to myself that Jem and I would soon grow up and not have much to learn, at most algebra." ( Harper Lee , who disturbs the nightingale )

In the irony of fate or the irony of history, an event takes the place of the commentator in verbal irony. In a sometimes cruel way, life devalues a principle of life or the illusion of a protagonist who, much to his surprise, has to endure the teaching in the position of a victim. In Friedrich Schlegel (1772–1829), an author of the German Romantic period, there is a reference to a soulful friend of nature who enters a lovely grotto and is splashed with water by it, which drives away its delicacy. Everyday examples today: a world swimming champion who drowns; a heartbreaker whose heart breaks; a racing driver being run over by a steamroller; a policeman who is being robbed; a cook choking on food, etc.

Under ridicule is understood today is generally a pejorative comparison hurtful intent. Mockery needs a victim for laughing at, maliciously teasing or ridiculing. Etymologically, it initially only meant: spitting out in disgust. Since the 18th century it has been used for birds that imitate the voices of other birds (mockingbird). Examples:

- “Man - a powder baboon” ( Christian Morgenstern ).

- A suitor in the palace to the beggar Odysseus: "The man is a living lantern, his bald head shimmers so much!" ( Odyssey )

As with ridicule, the meaning of cynicism has changed significantly over time. Modern cynicism is a theory of the futility of ethics and morals. In his opinion - or perhaps experience - resistance and human dignity in this world are senseless from the start. For a "cynical career" he is ready to sell his soul to the highest bidder. The cynic preaches adapting to power and oppression; he laughs at those who resist it and at humorists.

Originally, the attitude of Diogenes von Sinope (approx. 399–323 BC) was meant by cynicism , who lived his departure from the disintegrating polis as a self-assertion in the shameless existence of the naked individual. Diogenes vegetated “like a dog”, in other words: “cynical”, which did not mean “viciousness”, but a life in poverty and contempt by his fellow citizens.

A joke causes a laugh through sudden insight into an unexpected context. A joke is essentially based on a surprising combination and association. It needs to be broken down into an introduction, transition and punch line, conveyed by leitmotiv words that are often used in two ways. While irony, ridicule and cynicism require a specific individual or social group as an opponent or victim, third parties are possible for a joke, but not necessary: “Question: What kind of good joke is there? Answer: One year in prison. ”Success depends on the clarity of the form, the brevity of the exposition and the confrontation of the meanings or the characters in direct speech.

According to Sigmund Freud's great study The Joke and its Relationship to the Unconscious , joke is created by shifting the meaning to another level via the unintended secondary meaning or by condensing it with replacement (penetration, e.g. of two idioms) or without replacement (use of the double meaning , but which is also a kind of shift).

Strange people

Anyone who makes others laugh is considered funny . Those who practice laughter on a commercial basis sometimes slip into a predefined role or mask. These strange people or characters often have two complementary sides: a deplorable simplicity and an ingenious creativity. With these two sides, they give a human face to the connection between weakness and strength that is constitutive for humor . The success of comedian couples like Oliver Hardy and Stan Laurel (aka "Dick and Doof") or Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis depended on how they kept reinventing these complementary roles and their distribution among themselves in their films or on stage . The British-American writer PG Wodehouse has contrasted these dialectical character masks in many of his novels in the characters of Bertram Wooster and his servant Jeeves .

Historically, “funny characters” appear in a long line of people, from the jokers of antiquity to our cabaret artists and comedians today, privately and in public. Her humor changes from laughing at herself to an attack on public figures, social groups or institutions.

The comic stage character in the spiritual drama of the Middle Ages heated up the audience with rough jokes. The character was usually played as a hungry plebeian who, with a wicked joke, asserted his interests against the wealthy layers of the cities. This figure became the buffoon , later the puppet and even later the clown in the circus.

In Shakespeare's Midsummer Night 's Dream , Zettel, the weaver, is the comical figure: Puck occasionally casts a donkey's head on him, he plays in the “red beard, the very yellow one”, and as Pyramus says: “A voice I see; I want to go to the gap and see if I can't hear my Thisbe face clearly. "

One of the most important German writers not only of humor was Jean Paul (actually: Johann Paul Friedrich Richter, 1763-1825), who created a whole series of "comic characters". His field preacher Schmelzle, for example, has been hit by a lot of vices that make life difficult: Schmelzle suffers from an impractical point of view, cumbersome precautions and speech, he goes into transparent exaggerations and his logic is capricious. Schmelzle almost threatens to succumb because of these weaknesses, but can - and this is the required second side of a funny person - at least survive because of his great creativity.

With the circus clown, an everyday intention is hindered by an unwanted association or an often repetitive external disturbance and leads to clowning. The creative victory in the fight against the problem of the object is its eventual re-function, the invention of a new purpose.

history

In the culture of ancient Greece , people laughed in public places in the theater, at festivals and in the streets: quick-witted men mocked passers-by or influential citizens of their city. In the private sector since about 550 BC BC. Jokers who relied on collections of jokes in scrolls as a professional basis. The habit of insulting was deeply ingrained in the culture of revelry, but with the collapse of the Greek polis , laughter became dangerous to the haves. The great philosophers of antiquity (including Plato , Aristotle and Pythagoras ) demanded the taming of “coarse laughter” in favor of finer wit and cultivated irony: Laughter was frowned upon even in Plato's Academy .

Since it was expressly forbidden in Roman law to ridicule a citizen (in fact: a nobleman), Cicero repeatedly dealt with the inappropriateness of a joke that could otherwise quickly end a speaker's career. The humor of Plautus, on the other hand, in his comedies was much closer to the people and more of a carnival.

In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance , humor was more and more displaced from court culture and also from the church. The fool at the king's court lost his function, and laughter was considered the most obscene way of breaking the vow of silence in the monasteries , but of course their libraries also had collections of jokes. Humor became a theme of folk culture and city festivals ( Carnival, Mardi Gras and Mardi Gras ). Between around 1450 and 1750, a large number of so-called Schwank- or folk books with pranks, jokes and quick-witted answers circulated as ammunition for entertaining discussions and impromptu lectures. The humor of the taunts was often mocking or spiteful and was often directed against outsiders of society. Even Shakespeare processed ideas from contemporary farce books.

With the struggles between the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation , humor was used on the one hand to make the ideological opponent look ridiculous, on the other hand, the respective church feared falling victim to the laughter of the other side and tried to control and moderate it. Therefore, theologians also discussed whether and which jokes were allowed from the pulpit and whether Jesus could ever have laughed.

In the Enlightenment , humor was initially viewed as an offense against the ideal of seriousness and logical reasoning. Laughter was therefore initially forbidden in the French National Assembly, but was increasingly accepted as a means of political debate.

In the German pre-March , the number of caricatures, joke papers and printed satires exploded despite the censorship provisions of the Karlsbad Decisions of 1819. Humor “from below” became an important means of the democratic movement in the fight against aristocracy and absolutism. With parliamentarianism , folk culture and the cultivated laughter of the upper classes came closer together and are now permanently influencing each other under the influence of the mass media .

Humor is recommended as a management tool in some leadership teachings today . But whether humor, essentially a way out of inferiority and an intellectual form of resistance, is even suitable to be a management instrument in a hierarchical structure is worth further consideration, since these management methods are often only used in a manipulative manner.

to form

The number of forms associated with humor and laughter is high. Diversity and variety are perhaps an indication of the anthropological function of laughter: Laughing at others and at oneself is obviously an important relief from the hardships of life. According to Aristotle , humans are the only animals that have developed laughter - for him, laughter and being human belonged together.

In principle, the following manifestations belong to the area of humor:

- Forms of thought: mockery , irony , comedy , parody , sarcasm , self- irony , ridicule , joke , cynicism

- Written forms: anecdote , aphorism , gloss , limerick , satire , comic poetry

- Oral forms: running joke , pun , Krätzchen , Radio Yerevan , joke (joke), quick wit , dry humor , obscenity

- Behavioral forms: silliness

- Representations in theater and film: comedy , farce , farce , cabaret , slapstick , comedy , farce , the grotesque , slapstick , sitcom , satire

- Actors: clown , rogue , comedian , harlequin . Cabaret artist , diseuse , fool

- Pictorial forms: cartoon , comic , caricature

- Event types: April Fool's Day , Mardi Gras, Carnival and Carnival , gallows humor , irony , black humor , Therapeutic Humor

- Ethnic forms: British humor , Viennese charm , Jewish Humor , Rheinischer Frohsinn , Irish joke ,

- Special forms: Scientific joke , Klein-Erna joke .

See also

literature

- Monographs, edited volumes and specialist articles

- Alfred Adler : Connections between neurosis and joke (1927). In: A. Adler: Psychotherapy and Education - Selected Articles, Volume I: 19919-1929, Fischer Tb, Frankfurt a. M. 1982, ISBN 3-596-26746-3

- Henri Bergson : The Laughter. An essay on the importance of the comic. Luchterhand, Darmstadt 1988 (original title: Le rire. 1904)

- Peter L. Berger : Redemptive laughter. The funny thing in the human experience. Gruyter, Berlin 1998

- Vera F. Birkenbihl : Humor: You should be recognized by your smile . mvg, Frankfurt am Main 2003, 3rd edition, ISBN 3-478-08378-8

- Jan Bremmer , Herman Roodenburg: cultural history of humor. From antiquity to today. Primus, Darmstadt 1999, ISBN 3-89678-204-5

- Andreas Dickhäuser: Chemistry-specific humor. Theory formation, material development, evaluation. Logos, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-8325-4108-8

- Umberto Eco : The Frames of Comic 'Freedom'. In: Thomas A. Sebeok (Ed.): Carnival! Mouton, Berlin 1984, ISBN 978-3-11-009589-0 , pp. 1-9

- Sigmund Freud : The joke and its relationship to the unconscious. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1981, ISBN 3-596-26083-3

- Sigmund Freud : The humor. (1927) In: Alexander Mitscherlich u. a. (Ed.): Freud study edition Volume 4. Psychological writings. Frankfurt am Main 1969–1975, ISBN 3-10-822724-6 , pp. 275–282

- Harald Höffding : Humor as a way of life (The great humor). A psychological study. Teubner, Leipzig 1918; Reprint of the 2nd edition Müller, Saarbrücken 2007, ISBN 3-8364-0814-7 .

- Dieter Hörhammer: The formation of literary humor. A psychoanalytic contribution to bourgeois subjectivity. Fink, Munich 1984; extended new edition transcript-Verlag, Bielefeld 2020, ISBN 978-3-8376-5286-4 .

- Klaus Klages and Kuno Klaboschke: The worst thing for humor is when it comes to the worst , Verlag Up-to-Date-Kalender AG, Weyern 2003, ISBN 3-00-011112-3 .

- Stefan Lehnberg : Comedy for Professionals - The Handbook for Authors and Comedians, Bookmundo 2020, ISBN 9789463989510

- John Morreall: The Philosophy of Laughter and Humor. State University of New York Press, Albany / NY 1987, ISBN 0-88706-327-6

- Helmuth Plessner : laughing and crying . (1941) Berlin 1961

- Josef Rattner u. Gerhard Danzer : Master of great humor - drafts for a cheerful view of life and world . Verlag Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-8260-3863-1

- Jörg Räwel: Humor as a communication medium. UVK, Konstanz 2005, ISBN 3-89669-512-6

- Brigit Rissland, Johannes Gruntz-Stoll : The laughing classroom. Workshop book humor. Schneider, Baltmannsweiler 2009, ISBN 978-3-8340-0488-8

- Joachim Ritter : About laughter. In: Joachim Ritter: Subjectivity. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt / Main 1974, ISBN 3-518-01379-3 , pp. 62-92

- Oliver Roland (Ed.), Humor in the Church - The Christian Witz. 2nd edition, AZUR, Mannheim 2008, ISBN 978-3-934634-25-1

- Kai Rugenstein: humor. The liquefaction of the subject in Hippocrates, Jean Paul, Kierkegaard and Freud. Fink, Munich 2014, ISBN 978-3-7705-5703-5

- Wolfgang Schmidt-Hidding (ed.): Humor and wit. Hueber, Munich 1963 (European Keywords, Volume 1)

- Irka Schneider: Humor in advertising. Practice, opportunities and risks. VDM, Saarbrücken 2005, ISBN 3-86550-116-8

- Erhard Schüttpelz: Humor. In: Gert Ueding (Hrsg.): Historical dictionary of rhetoric. Vol. 4. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1998, 86-98, ISBN 978-3-484-68108-8

- Thorsten Sindermann: About practical humor: Or a virtue of epistemic self- distance Königshausen & Neumann, Frankfurt 2009, ISBN 3-8260-4016-3

- Werner Thiede : The promised laugh. Humor from a theological perspective. Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 1986, ISBN 3-525-63350-5 (Italian translation 1989).

- Michael Titze , Christof T. Eschenröder: Therapeutic humor. Basics and Applications. 4th edition. Fischer, Frankfurt / Main 2003, ISBN 3-596-12650-9

- Rüdiger Vaas : brains and humor. In: Universitas. Vol. 63, No. 745, July 2008, pp. 664–693 (review article on the neurobiological basis of humor as well as psychological and evolutionary aspects)

- Friedrich Wille : Humor in Mathematics . 6th edition. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2005, ISBN 978-3-525-40730-1 (How to solve supposedly hopeless situations with the help of mathematical constructions (and make you smile), e.g. how do you catch a lion in the desert?).

- Anton C. Zijderveld : Humor and Society. Styria, Graz 1976

- Heinrich Lützeler : Philosophy of Cologne humor. Peters, Hanau / Main 1954, new edition by Bouvier Verlag , Bonn 2006

- Trade journals

- Humor: International Journal of Humor Research . Published by the International Society for Humor Studies (ISHS). Quarterly, 1988-. ISSN 1613-3722

Web links

- Literature by and about humor in the catalog of the German National Library

- John Morreall: Philosophy of Humor. In: Edward N. Zalta (Ed.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Aaron Smuts: Humor. In: Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy .

- Fritz Mauthner , zeno.org: "Humor" in the dictionary of philosophy (1923)

- humorinstitut.de

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c Duden: The dictionary of origin. Mannheim 2007, Lemma Humor.

- ^ Lothar Fietz: The birth of the English comedy in the field of tension between sacred and profane. In: Anja Grebe, Nikolaus Staubach (ed.): Comedy and Sacrality. Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2005, pp. 156-163.

- ↑ JE Röckelein: Elsevier's Dictionary of Psychological Theories . Elsevier, January 19, 2006, ISBN 978-0-08-046064-2 , p. 285.

- ↑ Aristotle: Poetics ,

- ^ M. Tullius Cicero: De oratore

- ↑ Sigmund Freud: The joke and its relationship to the unconscious

- ↑ T.Dramlitsch: How the joke came into the world , Berlin ISBN 978-1549775802

- ↑ Rahn, Horst-Joachim: Successful team leadership, 6th edition, Hamburg 2010, p. 114