Temperament theory

The doctrine of temperament is a personality model derived from ancient humoral pathology , which categorizes people according to their basic nature. From a scientific point of view, the model, like humoral pathology, is outdated and no longer plays a role in modern personality psychology .

The teaching is characterized by its division of the overall temperament of humans into four basic temperaments , which in turn relate to the overall abundance of the human constitution (physical and psychological), but also to the overall abundance of the world around us.

The theory of temperament is still used as a historical basis in Waldorf education and occasionally in everyday psychology .

Ancient and Middle Ages

Origins of teaching

The doctrine of temperament of modern times goes back to an Aristotelian-Galenic teaching structure, which is based on the four-element theory and the humoral pathology (four-juice theory), which Hippocrates of Kos (Greek doctor, approx. 460-370 BC) is ascribed and is shown particularly clearly in the text "The nature of man", which was probably written by Polybos, the son-in-law and student of Hippocrates.

Development of the theory of temperament

The link between the doctrine of four juices and the doctrine of the four temperaments was made by Galenus of Pergamon , who assigned a temperament to each of the four hypothetical juices ("humores") of the body . Depending on the predominance of one of these four imaginary humors, the associated temperament is particularly evident. Galen took up a view that in certain areas, e.g. B. melancholy , had already been formed and systematized it:

- (Red) blood ( Latin sanguis , Greek αἷμα, háima ): sanguine (αἱματώδης - cheerful, active)

- (White) mucus ( gr. Φλέγμα, phlegm ) phlegmatic (φλεγματικός - passive, cumbersome)

- Black bile ( gr. Μέλαινα χολή, Melaina Chole ): melancholic (μελαγχολικός - sad, thoughtful)

- Yellow bile ( gr. Χολή, cholḗ ): choleric (χολερικός - irritable and excitable)

In the Middle Ages, Galen's theory of temperament was supplemented by assigning elements, directions, seasons, "planets", signs of the zodiac and keys.

| Traditional names | Animals | also | Element and astrological associations | Further assignments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanguine | lion | Hare,

monkey |

Air (Jupiter):

|

Spring, morning, childhood, warm and humid, heart |

| Choleric | cat | lion | Fire (Mars):

|

Summer, noon, adolescence, warm and dry, liver |

| Melancholy | deer | Moose,

bear |

Earth (Saturn):

|

Autumn, evening, adulthood, cold and dry, spleen |

| Phlegmatic | Ox | lamb | Water (moon):

|

Winter, night, baby age / old age, cold and damp, brain |

In the history of art, mainly processed and represented by Albrecht Dürer (as in the picture " Melencolia I from 1514"), a relationship between the temperaments and the four rivers of Hades was repeatedly established in the representation of Greek and Roman mythology .

18th to 20th century

Based on the four traditional temperaments in 1746, Johann August Unzer postulated some “mixed” temperaments, for example among “melancholy choleric” or “choleric melancholic”.

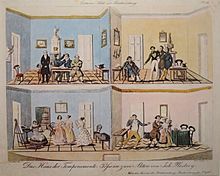

Johann Nepomuk Nestroy wrote the farce Das Haus der Temperamente in 1837 , in which the stage shows four apartments that are inhabited by four families with different temperaments.

The doctrine of temperament was accepted for many centuries and inspired modern personality psychologists such as Hans Eysenck (1916–1997), who in his personality circle the trait "unstable" between melancholic and choleric, "extroverted" between choleric and sanguine, "stable" between sanguine and phlegmatic as well as " introverted ”between phlegmatic and melancholic.

Rudolf Steiner , the founder of anthroposophy and who inspired the founding of the Waldorf School , developed a variety of the theory of temperament in addition to a large number of theses relating to pedagogy. Like its Greek predecessor, this divides the overall temperament of humans into four basic types, whereby there can be great one-sidedness of one or more temperaments in the respective individual, so the four temperaments occur in different strengths and characteristics in the respective individual .

As an example of the properties and meanings of a very specific temperament, according to Steiner, only people who are “tempered” on one side can be used, who can then face certain circumstances in life with great difficulties and other circumstances with great strengths.

In 1901/02 the Danish composer Carl Nielsen created his 2nd symphony with the title “The Four Temperaments”. In 1940 Paul Hindemith composed a composition of the same name for string orchestra and piano (premiered as a ballet in 1946).

See also

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Helmut Zander: Anthroposophy in Germany . Theosophical worldview and social practice 1884–1945. tape 1 . Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-525-55452-4 , p. 1408 f . Detailed presentation, not only in relation to anthroposophy

- ↑ Cf. Christian Rittelmeyer: The temperaments in Waldorf education . A model for checking their scientific nature in: Harm Paschen (Ed.): Educational Approaches to Waldorf Education - Wiesbaden 2010.

- ↑ Heiner Ullrich: Anthroposophy - between myth and science. An investigation into Rudolf Steiner's theory of temperament . In: Pedagogical Review . No. 38 , 1984, ISSN 0030-9273 , pp. 443-471 .

- ↑ Harald Schmidt: Temperament theory (modern times). In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil , Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte. De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , pp. 1382 f .; here: p. 1382.

- ^ J. van Wageningen : The names of the four temperaments. In: Janus. Volume 23, 1918, pp. 48-55.

- ↑ Gundolf Keil : Humoralpathologie. In: Werner E. Gerabek , Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil, Wolfgang Wegner (eds.): Enzyklopädie Medizingeschichte . De Gruyter, Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-11-015714-4 , pp. 641–643, here: p. 642.

- ↑ a b c d Magistrate of the city of Langen: City of Langen - The fifth quarter. Langen 2008, Vierröhrenbrunnen pp. 40–41

- ^ Gernot Huppmann: Anatomy of a bestseller. Johann Unzer's weekly “The Doctor” (1759–1764) - a review essay submitted later - In: Würzburger medical historical reports 23, 2004, pp. 539–555; here: p. 546.