De oratore

De oratore ( Latin "About the speaker") is a fundamental work by Cicero on rhetoric , in which the requirements for the speaking profession, the nature of rhetoric, the structure of the speech , questions of style and the moral and philosophical duties of the speaker are discussed. The font is designed as a dialogue between Lucius Licinius Crassus and Marcus Antonius Orator , Cicero's teachers and role models, which began in 91 BC. BC, shortly before Crassus' death. Cicero has it 55 BC. Published anddedicated tohis brother Quintus . It is one of Cicero's major works.

The work is divided into three books: In the first book, Crassus discusses the requirements for the speaking profession and from there arrives at a description of the ideal speaker (style qualities). The second and third books contain a presentation of the parts of the art of speaking (styles and peripatetic theory) before, at the end, in an excursus, in addition to the previously discussed technical, above all moral and philosophical qualities are required of the speaker: He should master rhetoric and philosophy , not only (as was often claimed at the time) one of these two disciplines.

Emergence

Cicero's main rhetorical work was written at an advanced age as the speaker and politician and is nevertheless one of the first works he wrote on rhetoric. At the time of publication, his early writings only included de inventione, which dealt with the only subject of how a speech was to be written. It thus represented a chapter from many works of rhetoric and instructions of the time, especially from the Greek culture. However, this was at most an excerpt for a manual presentation. Cicero wanted to make up for the failure of a comprehensive set of rules with the script, as his youth script was no longer sufficient for the experience and dignity of his age, as he himself says ( "quae pueris aut adulescentulis nobis ex commentariolis nostris incohata ac rudia exciderunt" ).

The fact that the work became a dialogue and not a simple manual presentation can be explained by the circumstances of its writing. The actors of the dialogue in de oratore are in September 91 BC. BC already in unfavorable circumstances shortly before the outbreak of the events that led to the alliance war and the later civil wars of Sulla and Marius. The Roman character that the dialogue acquired through these political events permeates the work with reference to Cicero's own circumstances, who not only embarked on a less active political career due to the first triumvirate , but withdrew to writing against the backdrop of the crisis of the republic . At the time of this vita contemplativa the triumvir Gaius Iulius Caesar ruled in Rome, from whom Cicero initially still hoped for political instruction and influence. Over time, however, he distanced himself from Caesar's policies and came under criticism specifically. The dialogue allowed Cicero to present his views several times through several people and thus to be able to more convincingly present political critics who considered Roman less suitable for intellectual rhetoric an ideal speaker who was also a statesman. The ideal speaker was therefore also a model for Cicero's hoped-for image of the Greek educated and politically sublime Roman statesman.

Occurring persons

The opinions of the people portrayed in de oratore are largely Cicero's opinions and his knowledge is conveyed through the respective characters. Mainly the people appear to pay tribute to them as great speakers of the republic. The fictionality corresponded to the literary genre and Cicero repeatedly built in 'real' passages in order to clarify this real relationship to himself.

Lucius Licinius Crassus, the speaker of the first and third books, was himself interested and involved in the education and study of Cicero. Cicero had a deep admiration for him, so that he wanted to dedicate the books to his and Antonius' memory. Cicero therefore remembers Crassus' last speeches in the Senate in detail at the beginning of the third book. Crassus' speeches in his own time were characterized by a lot of wit and the ability to win the audience over to his arguments with an effective lecture. This included his participation in the causa Curiana 92 BC. Or a speech that he is said to have given very successfully against the allegations about his luxurious lifestyle. He was influenced by Greek stylistic ideals of rhetoric.

Marcus Antonius, the grandfather of the later opponent of the octave and triumvir of the same name , had also distinguished himself in Crassus' time as a court speaker in the defense of important politicians who sued the consulate of Marius and later against Sulla .

During the dialogue, important speakers from the late republic appear in several places, some of whom also belonged to Cicero's teachers: Gaius Aurelius Cotta , Publius Sulpicius Rufus , Quintus Mucius Scaevola , Quintus Lutatius Catulus and Gaius Iulius Caesar Strabo Vopiscus , who speaks about the joke .

construction

Greek design models

The structure of the entire work follows models from literature and the common thematic classification of rhetorical stylistic qualities from Greek, which the Peripatetic Theophrastus of Eresos , a disciple of Aristotle , established for scientific rhetoric in his work Peri lexeos . The style qualities are correctness, clarity, appropriateness and jewelry / beauty. Cicero names three of them at the beginning of his philosophical work de officiis ("[...] quod est oratoris proprium, apte, distincte, ornate dicere"). A fifth quality, brevitas , was added to the peripatetic genera later through the stoic teaching . Contrary to the schematic representation of the Greeks, Cicero combined the qualities with his demand for a universal education for the speaker in order not to focus on the theoretical weight of rhetoric. Cicero therefore places Antonius in front of the peripatetic theory, which Crassus discusses in the third, with the presentation of a practical implementation of the styles (finding material, arrangement, practice) in the second book.

Another design model are the Platonic dialogues , from which Cicero takes specific themes such as the imminent death of the educated Crassus, who recalls the imminent death of Socrates in Phaedo . Scaevola, too, who bids farewell to those who speak at the end of the first book, has its counterpart in Cephalos, who withdraws at the end of the first book of Politeia . At the end of the third book, Hortensius is covertly announced as the new orator's hope, which refers to the announcement of Isocrates in Phaedrus , a student of Plato who, at least in his teaching , had distanced himself from the sophists and thus for Plato his idea of a new one that served philosophy Embodied rhetoric.

Book 1

1–23 In the Proömium of the first book, Cicero unfolds the conception of the work in front of his brother and particularly addresses the question of why there are so few outstanding speakers compared to a large number of famous scholars. He thus anticipates the topic that rhetoric was hardly a remote specialist science, because important statesmen and philosophers had rhetorically just as brilliantly accomplished. Rather, it was a few who shone exclusively in speech, while the rhetoric was also inherent in other sciences and activities in public life.

Fundamental themes of Proömius are the contrast between rhetoric and other disciplines where Quintus and Cicero oppose each other. Cicero uses examples to show that his consideration of speech implies other types (16 ff.). The second theme is the contrast between ideal and practical speech, represented in the argument that the Roman orator is too busy for a theory of speech (21) and that the Greeks also limited the art of speaking. Thirdly, there is the difference between Greeks and Romans (1–13), which is expressed in the fact that the Romans mostly had Greek teachers, but their talent ( ingenium ) should be much higher (15). Right at the beginning, Cicero addresses a fourth topic, the question of the otium. The diligent study of speech can only be realized if the Roman, who usually lives in the equilibrium of otium and negotium, finds the leisure to realize it. Since this is not the case in state affairs, because the Romans are almost always busy (21f.), The Greeks could deal with the subject differently. Fifth, Cicero mentions degrees of familiarization with rhetoric. Ingenium and exercitatio are enough for Quintus (1–5) . For Cicero, on the other hand, also include studia (diligent efforts), besides usus (utility) and exercitatio also ars (artistry) (14f. 19) and, like the Greeks, studies with otium . A sixth topic is the connection between words and content. A speaker who is not familiar with what is being said falls into hollow chatter ( 17.20 ), verba inania or inanis elocutio . For the types of rhetoric, three definitions can be made from the topics:

- narrower term of rhetoric, exclusively for practical speeches on the forum (according to Quintus point of view)

- Another term of rhetoric, for the forum, but formed in as many sciences as possible (Cicero's view)

- any form of verbal communication ( dictio ), (theoretical postulate of the ideal speaker in all situations)

24–95 After addressing the brother, the characters appear, the reader learns the time and place of the conversation about the Cicero's report. Cicero's explanations from the introduction are immediately taken up by Crassus, beginning with a song of praise to the art of speaking, which extends to all areas and to all types of public life. Scaevola subsequently restricts this praise to court speeches and political speeches (35ff.). Crassus takes the prerequisites that, according to Scaevola, a court speaker must bring and now again shows that they are used in all forms of scholarly speech (45–73). Crassus' argument is that the speaker can only really shine in his art if he is familiar with the technical terminology and theories of philosophy, mathematics , music and all other general and special arts. He speaks not only against Scaevola, but especially against the Greek ideas of rhetoric, according to which philosophy should be strictly separated from rhetoric. In addition, Antonius and Crassus report disputes in Athens , especially with the local academic Charmadas . He then draws a picture of the ideal speaker who is universally educated and who uses rhetorical expertise in an exemplary manner through expression and choice of words, both in theoretical and practical terms. Scaevola recognizes the description of the ideal speaker, who of course could not have existed, more in relation to the outstanding man in Crassus (76), who admittedly is modest that he is so highly praised by the priest, but indirectly agrees that he accepts one or the other theoretical deficiency is excellent. This self-assessment of Crassus comes very close to Cicero himself (78). As a result of the dialogue, Antonius also gives his opinion of the ideal speaker (80–94). He considers the ideal rather than the position of Crassus especially from a pragmatic side. His perspective concerns the demands and efforts of the practical lecture and the knowledge of philosophy, which he sees incompatible with the sophistic claim of a comprehensive education in the theory of speech.

96-106 The first part of the book is followed by a transition. The students of Crassus and Antonius want an overall presentation of Greek and Roman rhetoric, which the teachers willingly provide and thus lead to the second part, which fills the rest of the day in dialogue and at the same time the remaining space of the first book.

107–262 For Crassus and Antonius, it is not a scientific theory of speech that counts, but the prerequisites for a successful lecture in practice. These include the speaker's ingenium and natura , i.e. H. the natural and especially the intellectual abilities that he needs for the great task of rhetoric (113–133). It also includes studying , the constant eagerness to learn and also knowing the role models in the speech excellently (134–146). Finally, the speaker needs a great deal of academic and written practice associated with subject education (147–159). The following are examples of these three requirements of the speaker and, through special requests to Crassus, in detail in law and court . From these explanations, too, Crassus comes back to the conclusion how high the eloquence is to be assessed for all sciences and vice versa (201–203). Antonius, on the other hand, limits the knowledge and requirements to rhetoric and consistently denies the mixing of rhetorical training with politics (214 ff.), Philosophy (219–233), civil law (234–255) and all the disciplines that Crassus listed. The discussion ends in contrast and with the farewell of the high priest Scaevola, who announces that he can no longer take part in the conversation.

Book 2

1–11 The second book begins again with a Proömium, which this time contains in the manner of Proömien proper a praise to the people involved and the material dealt with. For Cicero, the dialogue should show posterity how far Crassus and Antonius came in their knowledge and fame in the art of speaking to the ideal of the speaker.

12–50 After the Proömium, Antonius begins to speak, whose lecture fills the entire second book. He has a much larger and more well-known audience, because Catulus and Caesar join the audience right at the beginning. Like Crassus the day before, it begins with praise for the rhetoric and some remarks on theoretical rhetoric. Antonius then explains briefly (38–50) that an overview of the speeches makes it unnecessary to list expressions for each species.

51–92 In order to show that the possibilities of expression are inherent in individual genres, Antonius gives an excursus on Roman historiography (51–65) in which he demonstrates his education and his intellectual qualities. He proves the same in the art of abstract discussion (64–84), for which theoretical rhetoric is just as useless. His personal ideas (85–92) relate to practical experience. For this he first highlighted the role model effect of the teacher, who passes on his knowledge to the students in the sense of imitatio . The example continues between Sulpicius and his teacher Crassus (84–98).

92–113 After the remarks on the importance of the practical lecture, Antonius gives exemplary exempla in the individual epochs of Greek eloquence (92–95). Concrete rules emerge from them, which he issues for observance, in particular the finding and critical examination of the material for the argument, which is usually more complicated to look at than school examples. An excursus follows into the theory of stasis , which is a methodical framework for finding the issue at issue (104–113). From this doctrine he comes to the important topic of finding the material, the inventio . The aim of the question of fact concerns the effect that the speaker wants to achieve and which consists of the three main points , to prove the thesis as correct ( probare ), to win the sympathy of the listener ( conciliare ) and to arouse affects ( movere ).

114–177 Antonius now sets out the prescriptions for the individual goals. He begins with the proof of the thesis and the question. In order to fulfill this point, the speaker has to trace individual cases back to a genre-specific general case . This means that he does not have to start afresh with the scientific treatment of each topic each time, but can assign it to his theoretical knowledge of the genre. At the same time, depending on experience, diligence and insight into the matter, he can already fall back on certain basic ideas as to how cases brought to him are to be assessed. This thought leads Antonius to the rules of the Greek schools of philosophy, whose value for speech he discusses afterwards (151–161). He then gives examples of how such basic ideas are to be applied and which genera must be used for certain reasons of evidence.

178–216 The second and third points, how the speaker wins the hearts of the audience and influences the minds, follows with an explanation of the doctrine of affect (185–216).

216–306 When Antonius addresses humor and wit to win over the audience, Caesar interrupts him with a comprehensive lecture, which he follows with the golden rule of every material discovery, namely to avoid anything that can harm the client and his cause ( 290-306).

306–367 At the end of his lecture, Antonius gives instructions on how to arrange the material found (307–332) and concludes with specific rules for speeches on specific occasions, such as politics (333–340), the eulogy and the invective (340 -349). Finally, there are notes on mnemonics and thanks to the audience, to whom he gives a preview of the third book in which Crassus wants to discuss the tasks of a speaker.

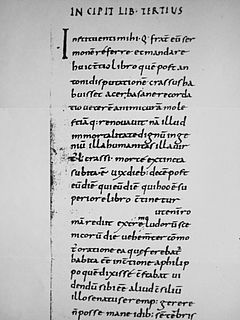

Book 3

1–16 In the Proömium of the third book, Cicero reminds his brother Quintus once again of the beginning of the complete work: of the importance of speech in politics, especially against the background of the impending state crisis. The function of this writing will also be to keep the memory of the speaking people alive. The subject areas that Crassus will deal with technically in this book were already addressed and comprehensively prepared in the first book.

19–143 Crassus deals in this book primarily with the delivery method and the style of speaking. The first part therefore follows the usual presentation of the four Aristotelian style qualities. In addition, Crassus wants to prove in this part that philosophy benefits theoretical rhetoric, and to point out why. Because his style has to build on the comments on the content that the previous speaker Antonius comprehensively explained in the second book, and in order to strike the link between philosophical content and rhetorical form, he first draws a unity between art and content (19-25 ). Crassus then slowly works his way through the stylistic qualities to the climax of the book, namely the statement in chapter 143 that a speaker with complete philosophical knowledge surpasses all others. To this end, he first describes that the function of stylistic qualities is to bring together the talents of each student through the individual arts (25–37). Then he comes to the effect of linguistic correctness (37–48), clarity (48–51), beauty and appropriateness (52ff.). On the basis of these last two points, Crassus denounces contemporary school rhetoric and demands a unity of intellectual and expressive power and political sentiment measured against ancestors. In it Crassus regrets the un-Roman separation of philosophy and rhetoric in Socrates. Then he checks which schools of philosophy have any positive use for the speech. With Epicureanism and Stoicism , he arrives at a negative judgment, with academic and Aristotelian teaching, a positive judgment . In the latter in particular, the path back to the unity of mind and language is inherent, which Crassus considers difficult to take but not impossible to walk (56–90). As a censor, Crassus himself would have had the schools of rhetoric banned (91–95). From debauchery, Crassus returns to the last two style qualities, adorned and beautiful to speak, and forbids both the occasional showmanship and the weariness of ornamentation. Rather , an important method is amplificatio , the development of an important argument for the locus communis . The speaker needs the latter in dialectics as well as for assessing legal cases and consequently Crassus divides them into concrete and abstract questions. (96-104ff.) This is followed by a repetition of Antony to find a topic and a wealth of content, the structure of which a man of talent would choose in such a way that no further rules are needed for perfect expression. Catulus subsequently noted this effect of the structure of speech among the Sophists and regretted that their teaching had been forgotten by Crassus (104–131). Crassus takes up the reproach and shows where thematic narrowings also take place in other areas, whereby he finally makes his point once again extraordinarily clear that universal education is the ideal of the speaker to strive for:

“Sin quaerimus, quid unum excellat ex omnibus, docto oratori palma danda est; quem si patiuntur eundem esse philosophum, sublata controversia est; sin eos diiungent, hoc erunt inferiores, quod in oratore perfecto inest illorum omnis scientia, in philosophorum autem cognitione non continuo inest eloquentia; quae quamvis contemnatur ab eis, necesse est tamen aliquem cumulum illorum artibus adferre videatur. ”

“But if we ask what is the only thing that stands out from all of them, the palm of victory has to be given to the learned speaker. If you accept that he is also a philosopher, the dispute is resolved. But if one wants to distinguish between them [philosophers and speakers], they will be weaker in so far as the perfected speaker has all the knowledge of those philosophers at his disposal, but the knowledge of the philosophers does not automatically have eloquence at the disposal. This is indeed despised by them, but one should clearly see that it is, so to speak, the icing on the cake for the expertise of those [philosophers]. "

143–147 After Crassus' lecture, there is a brief silence and an interim discussion.

147–227 In the last part of the book, Crassus sets his theme of right formulation, i. H. of the expression. The following is a long breakdown of the resources for word decorations into two groups. First he explains that how individual words should be given a certain ornament (148–170), then how the words work well together with regard to questions of word order (171f.), Rhythm and periodization (173–198). This is followed by an emphasis on the overall impression of a speech and the three types of expression for the respective speech situation, the simple style ( genus tenue ), the moderate style ( moderatum genus ) and the impressive style ( genus grande ) (199). Examples of application follow different ideas before Crassus closes his speech with rhetorical stylistic devices , the demand for the appropriateness of the style of speech ( aptum , also decorum ) and the manner of presentation ( actio ) (213-227).

227–230 In the short epilogue, the audience thanked the two speakers for their explanations and gave a hopeful outlook for the future. Without naming him directly, allusions are made to the son-in-law of Catulus, Quintus Hortensius Hortalus , who was expected to come close to the Ciceronian ideal of speakers and thus develop politically into a right-wing statesman.

expenditure

- Marcus Tullius Cicero: Scripta quae manserunt omnia. Fasc. 3., De oratore, ed. v. Kazimierz Feliks Kumaniecki, (= BT), Teubner: Stuttgart / Leipzig 1995 (ND Leipzig 1969) [older standard edition]

- Marcus Tullius Cicero: Libros de oratore tres continens, ed. v. August Samuel Wilkins (= Marci Tullii Ciceronis Rhetorica, Vol. 1), Oxford 1988 (ND Oxford 1901), 13th ed.

Translations

- James M. May / Jakob Wisse: Cicero. On the Ideal Orator lat./engl., Oxford University Press, New York / Oxford 2001.

- Cicero: De oratore - About the speaker . lat./dt., ed. v. Harald Merklin , (= Reclams Universal-Bibliothek, vol. 6884), Reclam, Stuttgart 1997, 3rd exp. Ed., ISBN 3-15-006884-3

- Marcus Tullius Cicero: De oratore - About the speaker . lat./dt., ed. v. Theodor Nüßlein (Tusculum Collection), Artemis & Winkler, Düsseldorf 2007, ISBN 3-7608-1745-9

literature

- Carl Joachim Classen : Ciceros orator perfectus. A vir bonus dicendi peritus ?, in: Die Welt der Römer, ed. v. Carl Joachim Classen / Hans Bernsdorff , De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1993, pp. 155–167.

- Elaine Fantham : The Roman World of Cicero's De Oratore. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2004, ISBN 0-19-920773-9

- Wilhelm Kroll : Studies on Cicero's writing de oratore, in: Rheinisches Museum für Philologie. 58: 552-597 (1903).

- Anton Daniël Leeman: The structure of Ciceros De oratore I, in: Ciceroniana Hommages à Kazimierz Kumaniecki. Leiden 1975, pp. 140-149.

- Anton Daniël Leeman u. a .: Marcus Tullius Cicero. De oratore libri tres. Vol. I – V, University Press C. Winter, Heidelberg 1981–2003. [Commentary and standard work in collaboration with other classical scholars]

- Harald Merklin: System and theory in Ciceros de oratore, in: Würzburger yearbooks for ancient studies. NF 13 (1987), pp. 149-161.

- Jakob Wisse: De oratore. Rhetoric. Philosophy and the making of the ideal Orator, in: Brill's Companion to Cicero, ed. v. J. M. May. Leiden / Boston / Cologne 2002, pp. 375-400.

Web links

- Latin text in the Latin Library

- German text at mediaculture online : translated, introduced and explained by Raphael Kühner

Individual evidence

- ↑ Cicero, De oratore 1.5.

- ↑ See Jakob Wisse: De oratore. Rhetoric. Philosophy and the making of the ideal Orator, in: Brill's Companion to Cicero, ed. v. J. M. May, Leiden / Boston / Cologne 2002, p. 377.

- ↑ Cf. Jakob Wisse: The intellectual background of the rhetorical Works, in: Brill's Companion to Cicero, ed. v. J. M. May, Leiden / Boston / Cologne 2002, p. 336.

- ↑ See Cicero, Ad familiares 7,32,2.

- ↑ Cf. Anton D. Leeman, Harm Pinkster, Hein LW Nelson: M. Tullius Cicero, De oratore libri III. Commentary, Heidelberg 1895, pp. 203ff.

- ↑ See Jakob Wisse: De oratore. Rhetoric. Philosophy and the making of the ideal Orator, in: Brill's Companion to Cicero, ed. v. J. M. May, Leiden / Boston / Cologne 2002, p. 376.

- ↑ See Cicero, De oratore 2,227.

- ↑ Cicero, De officiis 1,2.

- ↑ Wolfram Ax : The influence of the Peripatos on the language theory of the Stoa, in: F. Grewing (Ed.): Lexis and Logos. Studies on ancient grammar and rhetoric, Stuttgart 2000, pp. 74f.

- ↑ Jakob Wisse: De oratore. Rhetoric. Philosophy and the making of the ideal Orator, in: Brill's Companion to Cicero, ed. v. J. M. May, Leiden / Boston / Cologne 2002, p. 378f.

- ↑ Cf. Plato, Phaedrus 279a. 3ff.

- ↑ Cf. Anton Daniël Leeman: The structure of Ciceros De oratore I, in: Ciceroniana: Hommages à Kazimierz Kumaniecki. Leiden 1975, pp. 142f.

- ↑ See Jakob Wisse: De oratore. Rhetoric. Philosophy and the making of the ideal Orator, in: Brill's Companion to Cicero, ed. v. J. M. May, Leiden / Boston / Cologne 2002, p. 380.

- ↑ Jakob Wisse: De oratore. Rhetoric. Philosophy and the making of the ideal Orator, in: Brill's Companion to Cicero, ed. v. J. M. May, Leiden / Boston / Cologne 2002, p. 382.

- ↑ Jakob Wisse: De oratore. Rhetoric. Philosophy and the making of the ideal Orator , in: Brill's Companion to Cicero, ed. v. J. M. May, Leiden / Boston / Cologne 2002, pp. 383/389.