Literary history

Until the middle of the 18th century, the term literary history meant “ reports from the learned world ” and has been redefined since around 1830 as a field of national linguistically fixed tradition within which the artistically designed works are authoritative.

history

The history of literary historiography hides a break with the turn of the 19th century. Those who wrote literary history between 1750 and 1850 gave up their original topic - reporting from the sciences - at the end of the 18th century, and made the subject of precisely what had previously been considered unscientific, outside of literature : poetry , fictions .

The change in topic meant that the word “literature” had to be redefined in the 19th century. As the “area of linguistic transmission”, the definition was designed in such a way that the specialist sciences could continue to list their work in “bibliographies”. In the linguistic tradition, however - according to the new thesis of literary historiography of the 19th and 20th centuries - linguistic works of art took a central place - as the core of national traditions, as the field of the eternally discussed works, the field of aesthetics outstanding works, so the attempts to explain why dramas , poems and novels should be "literature in the strict sense". In the following, the emergence of literary historiography together with the change in subject will be briefly outlined.

From polyhistory to literary history, 1500–1650

Modern literary historiography begins in the 16th and 17th centuries as an attempt to report on the sciences - and that was "literature" until the 19th century. Initially - the advent of the printing press increases the hopes that exist here - the work of large-scale works applies, which is supposed to contain the entire knowledge of scholarship systematically like libraries . However, polyhistory already fails in its first attempts. The problem is not so much the emergence of the natural sciences . The polyhistorical projects are more difficult because they degenerate into ideological fixations from the start : their authors try to make philosophical and theological statements about how knowledge and the cosmos it encompasses are organized. The plans for order are immediately branded as scholastic , backward-looking, the content of the works themselves hardly come out of the compilation of information that is already available. Anyone who wants to use them has to laboriously familiarize themselves with the author's concept of order; he then handles heavy volumes that are only available in a few libraries. Criticism of existing knowledge, technical discussions, are hardly to be found in the polyhistorical works.

With the 17th century, three new groups of works gained importance:

- the alphabetically sorted lexicon ,

- the bibliographically oriented " Historia Literaria " or "History of erudition" and

- the literary journal .

The lexicon takes on the legacy of polyhistory as the work that the knowledge itself offers. Universal dictionaries remain rare projects. The market expanded with specialist lexicons and, from the beginning of the 18th century, with small lexica, newspaper or conversation lexica , which briefly offer knowledge in a portable format, geared towards the newspapers that rarely provide information about the historical locations.

The “Historia Literaria” or “History of Gelahrheit” (today erudition) becomes a bibliographical project. It offers small reference works that organize and subdivide the sciences according to all subject areas and research questions , and note down point by point which works are the most important in the respective field by scientists of which nation. These reference works are primarily bought by students and prospective scientists who can put footnotes in their own scientific work after them .

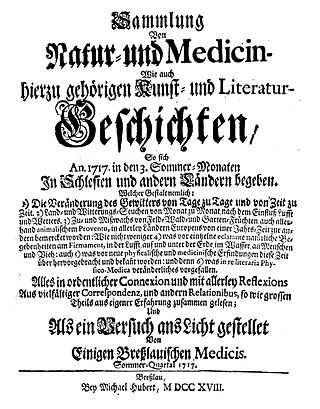

The literary journal became a hit on the book market in the second half of the 17th century. In monthly editions, it provides an overview of the most important new scientific publications and - with a scientific orientation - inventions . The reports offer excerpts from the works discussed, including page numbers for important quotations . At the end of the year, the recipient usually receives a register for the individual numbers , which enables him to use his scientific journal as a technical lexicon. The literary journal made a career around 1700 above all because it developed into a carrier of continued reasoning about current debates in research, while providing space for public debates from politics and religion .

In the course of the 18th century, the most important literary journals opened up to the area of belles lettres , which became a central field in the exchange of literature.

The triumph of the belles lettres , 1600–1750

The book market was divided early into two areas: that of literature for scholars and that of publications for the wider reading public, which required prayer books , the lives of saints, popular histories, and above all newspapers . Both areas were clearly different in design. Precious and finely printed, especially in Latin , the literature appeared in the four sciences of theology, jurisprudence, medicine and philosophy. In contrast, the cheap mass-produced goods appealed to the public in publications that were carelessly set with simple woodcuts.

In the 17th century a new, third market was created, the belles lettres . The name says it all: The publications offered here belong to the upper market segment, to the lettres, the sciences, the literature - but not to pedantic academic erudition, but to a field that is more characterized by its convenience, taste and demand. Fine copperplate engravings are offered here instead of cheap woodcuts, French and elegant modern national languages, instead of scholarly Latin or absurd language from the lower literature. The belles lettres market includes current scandalous histories, novels, memoirs, travel reports and journals. The public is aristocratic, bourgeois-urban, it includes women, who are denied academic learning, and learned readers who, in addition to their subject, have interests in current affairs.

The new market ranks in English under the French word or under the word "polite literature"; in Germany at the end of the 17th century it is the area of the “gallant sciences”, from the middle of the 18th century: the area of “beautiful sciences”, or, more elegantly, “beautiful literature”.

At the beginning of the 18th century, the literature review was still cautious about the new market. The Journal de Sçavans or, following it, the German Acta Eruditorum are scientific journals. However, with the boom in the journal market that emerged at the end of the 17th century, it clearly determined the endeavor to satisfy the expanding readership. For this purpose, the more popular sheets regularly allow individual reviews of publications from the field of belles lettres, which do not belong to literature in the current sense, but can also claim broader interest from scholars. The Germans, for example, review Acta Eruditorum 1713 completely unabashedly of the scandalous Atalantis Delarivier Manley , a book of revelation disguised as a novel of alleged machinations of the last London administration. However, the new subject of discussion only gained strength in the second half of the 18th century, when poetry conquered national debates.

Poetry becomes the subject of the national literary debate, 1720–1780

The " belles lettres " are only indirectly a forerunner of our current literature. In German, their market lives on with the fiction market , and this marks the most important differences: One can speak of the “literatures” of the nations, but there is only one single fiction. Literature is discussed by literary critics and literary popes. By contrast, fiction remained a market without a secondary discourse. Fiction encompasses literatures, but it offers infinitely more - almost everything that claims a broader interest is fiction in the book trade.

Our present-day conception of literature arose when, after 1720, national poetry - it did so primarily in Germany at first - attracted the interest of scholarship.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, poetry is little more than the domain of bound language. In the course of the 17th century, the opera in its playing forms of the Italian and French styles became the central location of poetic production. Poetry was published to be set to music. Add to this, despised by anyone with taste, panegyric and all the commercial poetry production commissioned for funerals, weddings, and anniversaries. At the beginning of the 18th century, poetry is most likely to be seen in a crisis - corrupted wherever it is commissioned and scandalous where it lends itself to opera and gallant songwriting. The 1720s and 1730s experience massive criticism of the operas, especially from the scholarly side. In the interests of public morality, Johann Christoph Gottsched and his fellow critics in German-speaking countries call for a reorientation of poetry in which Aristotelian poetics should come into play. The opera, the song, the cantata are not abolished, but it is stipulated that the public exchange does not apply to these areas - it applies, and this can be determined by the authors of current journals, since they have public access - a poetry that the Nation serves, produces great responsible writers, enables important discussions.

In the course of the 18th century, the result was a division of the market: on the one hand, the market for belles lettres continued and developed as an international market for fiction. On the other hand, as the 18th century progressed, authors could increasingly risk writing “sophisticated” poetry, poetry that only sells at the moment when critics discuss it and recommend reading it. A publicly discussed poetry emerges in relation to a market that is left to trivialization.

The “demanding” poetry, which claims to be socially recognized, gains in importance as the first generation of critics, who still demanded a return to Aristotle , gives way to a second generation that is open to the new bourgeois drama and above all the novel. While poetry has hitherto been discussed mainly on the question of how perfectly genre rules were adhered to, much more explosive discussions arise in the second half of the 18th century - those that Pierre Daniel Huet in 1670, without being heard, with his Traitté de l 'origine des romans came up when he proposed reading the novel and poetry fundamentally as fictional productions and thus as reflections of the current customs of a nation.

While the novel had developed into the most important medium of the chronique scandaleuse at the end of the 17th century , the scholarly criticism of the 18th century can call for novels that reform morals, novels that tie in with Samuel Richardson's Pamela .

The poetry discussion in learned journals gained public attention in the second half of the 18th century, especially in Germany, where it offered the best national arena for debate. Germany is divided territorially and denominationally; Apart from the scholarly, but thus elitist discussion, there is no broader, supra-regionally functioning field of debate. Here the demand for a German poetry that separates from the French, imitates the English and then emancipates itself from it, arouses public explosiveness in the struggle for national identity.

National literary history redefined itself, 1780–1850

At the end of the 18th century, antiquated literary historiography found itself in a crisis: The sciences are now increasingly oriented towards the modern natural sciences, the recapitulation of old authorities is becoming obsolete, and at the same time the public discussion of literature has changed: it is almost exclusively for novels, plays and poems .

The result of the development can be seen in the last old-style literary stories , for example in the outline of a history of the language and literature of the Germans from the earliest times up to Lessing's death by Erduin Julius Koch , 1 (Berlin: Verlag der Königl. Realschulbuchhandlung, 1795) . Like the old works of the Historia Literaria, the late 18th century literary history is a bibliography that is structured and subdivided into sections. However, the sciences now take up little space. The “beautiful literature” with the genres of poetry has conquered the work.

With the history of the poetic national literature of the Germans by Dr. GG Gervinus . First part. From the first traces of German poetry up to the end of the 13th century (Leipzig: W. Engelmann, 1835), the old project is transferred to the new: According to the title, the literature of the nation is its traditional poetry, but the new literary connoisseur provides how He opens in the preface, no longer a bibliography, but an interpretative narrative of how poetry unfolded in the different epochs of the nation - in the Middle Ages initially at the courts, then increasingly corrupted by the monks, in humanism dominated by scholars, finally in the 18th century liberated by an initially learned but then quickly learned criticism ...

The new literary history provides material for discussion, its topic is the character of the nation under changing cultural and political conditions - and it receives immediate replies from all political interest groups who must insist on their own account of literary history if they want to ensure that their issues are discussed publicly become.

In the background of modern literary history stands the modern nation-state from the middle of the century, which guarantees the literature of the nation, the greatest poets of the nation and the decisive epochs of their history public attention in cultural life as in all institutions of education. At the latest with the fact that the texts of national poetry in the 19th century in the public school system took on the functions to which religious texts seemed to be tailored up to now (namely to be interpreted and discussed, to give rise to individual reflection and orientation), literature has a New function gained: It is the field in which almost every question of society can be dealt with and will continue to be dealt with in school lessons - a field that no social group can ignore. From now on, the decisive factor is to determine the canon of literary works and to define their discussion. The competition about this takes place between authors who offer different funding for literature and a different approach to literature; it takes place in the media in dealing with literature - old and new, national and international - it takes place in the academic field between the different schools literary criticism, which ultimately provides society with model discussions.

Problems of an alignment of literary historiography

On the benefit of changing subjects that turned dramas, novels and poems into "literature"

The change of subject that the literary discussion got involved in by turning to dramas, novels and poems took account of public desiderata . It changed the book market, but above all it allowed literary studies to have a decidedly broader communication with society.

The de-scandalization of poetry and novel production

The scientific debate turned to poetic production and the production of novels mainly in reform offers. Current poetry production seemed to have strayed from the scientific discourse of the 1730s from the path set by Aristotle. Gottsched's comrades-in-arms avoided branding operas more decisively as a place of moral decline. However, they called for a drama that had its own meaning, made debatable statements, produced by responsible authors who became known by real names.

At the same time, the novel still seemed irreformable. At the end of the 17th century he had gone into the scandal business. Here, too, in the mid-18th century, the discussion about better and more responsible novels was in the room. What could not be abolished - the opera production and the production of scandalous novels - could (according to the new approach) be successfully reduced in public attention as a trivial production unworthy of any debate, which had to focus on the selected high works of art.

Indeed, at the end of the 18th century, mechanisms of responsibility took hold in the new literary production of poetry and novels. Authors stood behind their works and claimed the fame of having improved the morals of their nation with their works. The culture industry of the new nations gave the morally valuable production new value, whether it was letting students write “reflection essays” about the great poetry or establishing institutions such as the Nobel Prize for Literature, with which authors are honored who act as the “conscience of their nation”.

Indeed, the scandal production left the opera like the novel. Their new medium was journalism, which was given its own field with the tabloid press. That was not the end of scandalous novels, dramas, and poems - but the new scandals in literature are entirely different. Young authors are now rebelling against entrenched morals, against old aesthetics and outdated ideas of art; they are part of the struggle for responsibility in literary life. The scandalous novel of the early 18th century lives on in "investigative journalism" rather than in the novel of the 20th and 21st centuries. The market reform targeted by the early literary discussion actually came about.

The birth of literature from the spirit of secondary literature

Modern literary studies are based on the self-image that it is an observing, analyzing, scientific, secondary discourse. The literature is (it is widely statement of literary criticism) much longer than the literature. It has existed since the beginning of mankind, since the first traditions that were still oral. It finally ran into the “ literary genres ” right into contemporary literature - according to the established view. The secondary discourse turns to literature while maintaining scientific distance. In fact, it should be the other way around: the works developed in very different fields and were largely lost in the end, in the 1760s. Literary studies determined what “literature” should be. She created the literatures we study today. The great lines of tradition that exist today had to be reestablished in the 19th century: The “literature of the Middle Ages” was lost, the novels and dramas of the “Baroque” were unknown at the beginning of the 19th century. The past of literature had to be reconstructed. And in the present the intervention was even more drastic: the literature review decided in open dispute which works of the present and the most recent past should be discussed as literature, and which genres became literary genres.

The fact that literary studies defined literature for its own benefit in order to gain a broadly debatable topic is a delicate observation. If so, then all attempts to simply look at literature and grasp what literature actually is and what characterizes it are not what they claim. They are then actually attempts from the field of science to determine what literature should be and what should be done appropriately with it - interactions of literary criticism with the book market, with authors and with society that reads books and takes up discussions. The inconvenient solution then also explains why every definition of literature immediately attracts public opposition, which here must safeguard the most diverse interests in the literary debate.

Problems in dealing with “literature” that has been written since 1750

"Demanding" literature that has been created since 1750 specifically addresses criticism; it differs fundamentally from the previous production of novels , dramas and poems . With it we have indications in modern literature as to how it should be discussed. In addition to what the writers did to spark discussion, what the publishers did to get literary criticism.

Demanding literature is primarily sold through secondary discourse. Trivial novels can do without any public debate. A modern novel, a young playwright, on the other hand, are nothing if they fail to attract reviews, and they have won if they find broad acclaim in the features section . A more complete literary history of the modern age will encompass the entire literary life that gives the individual play and the individual novel functions in social life: existence in the book market, recognition in the press, treatment in schools and literary seminars at universities.

Problems in dealing with "literature" that was written before 1750

Our reconstructions of literary history remain problematic. Most of the connections that they establish should deserve another survey.

Today's literary genres did not exist

The concept of literary genres will have to be carefully questioned again in research. The fact that drama , epic poetry and poetry are the three great fields of literary tradition ignores the historical consistency of the tradition. One can postulate this with regard to Aristotle , but with it one is embarking on a follow-up to the scholarly criticism of the 17th and 18th centuries - a criticism that changed the market with precisely these statements.

The national literature did not exist

Our investigation of national literatures and the comparison of literatures through comparative literature are entirely questionable . The authors examined by us hardly knew the works of their literature before 1750. The production before 1750 is far more fair if one looks at it as one would look at the production of fiction today: as a single international current production that found national characteristics, but in which ultimately international goods in translations next to local books in the display cases came. The authors wrote for this market and delivered what it hopefully was not yet comparable at the place of publication.

Poetry before 1750 was not what literature is to us today

A renewed research into poetry production before 1750 could give the music-oriented fields central importance, and not do so in search of the “literary concept of the Baroque”, which was allegedly defeated in the end by an anti-operatic “literary concept of the Enlightenment”. There was a market in which opera flourished as poetry, and opposite it a scholarly criticism that viewed opera from a distance.

Before 1750 the novel belonged neither to poetry nor to literature

The novel was one before 1750, neither the poetry nor to "literature." - he was part of the "historical writings" and current in its production of novel moving toward the belles lettres whose virulentester and most scandalous part As to the meeting system is for the 18th Century still largely unexamined; what functions he previously fulfilled when he still largely affronted literary discussion, no less.

What determined public disputes before 1750 is largely ignored

Our exchange of dramas, novels and poems created a new place of social strife - with great success. Literature in the new sense supplanted the most important production to date, theology, on the book market and in general discussions. The exchange of dramas and poems developed with great dynamism in Germany in the late 18th century. It gained weight in the nationalism of German Romanticism.

France adopted the new literary debate after the French Revolution as worthy of the bourgeois state. German and French literary scholars finally offered England the first stories of English literature in a new shape - the nation, which had unbroken national discourses, saw no reason to change the meaning of the word "literature" for a long time.

Modern literary history asserted itself internationally and created the national philologies that existed today, and it inspired parallel foundations: art was redefined as the field of the visual arts, music entered into a competition between national musical art that began in the second half of the 19th century flared.

A more cautious approach to literary history will apply to public life before 1750 and its very own themes, and will have to be critical of literary criticism: it changed the market to which it turned, and it essentially created the field that we today call “ the literature "busy.

Works

- Christophe Milieu (Christophorus Mylaeus): De scribenda universitatis rerum historia libri quinque. Basileae, 1551, in it book 5 on “Historia literaturae”.

- Jacob Friedrich Reimmann : An attempt at an introduction to the Historiam Literariam. Rengerische Buchhandlung, Halle 1708.

- Georg Stolle: Kurtze Instructions for the History of Gelahrheit. 1, Neue Buchhandlung, Hall 1718.

- Johann Friedrich Bertram : initial teachings of the history of erudition; Collects a discourse on the question of whether it is advisable to trace Historiam literariam to schools and high schools. Renger, Braunschweig 1730.

- Johann Andreas Fabricius: M. Johann Andreä Fabricii. […] Outline of a general history of learning. Weidmann, Leipzig 1752.

- Hieronymus Andreas Mertens: Hodegetical draft of a complete history of learning for people who want to go to the university soon, or who have hardly got there. Eberhard Klett's blessed Wittwe and Franck, Augsburg 1779–1780.

- Carl Joseph Bouginé : Handbook of the general Litterargeschichte after Heumann's plan. Vol. 1 ff, 1789

- Outline of a history of the language and literature of the Germans from the earliest times up to Lessing's death by Erduin Julius Koch. 1 Verlag der Königl. Realschule bookshop, Berlin 1795.

- Johann Gottfried Eichhorn : General history of the culture and literature of modern Europe. Göttingen 1796–1799.

- Johann Gottfried Eichhorn: Litterärgeschichte. Johann Georg Rosenbusch, Göttingen 1799.

- Johann Gottfried Eichhorn: History of Literature from its Beginning to the Latest Times. Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 1805–1812.

- Ludwig Wachler: Handbook of the history of literature. JA Barth, Leipzig 1833.

- Introduction and history of ancient literature .

- History of literature in the Middle Ages .

- History of modern national literature .

- History of recent scholarship .

- History of the poetic national literature of the Germans by Dr. GG Gervinus. First part. From the first traces of German poetry to the end of the 13th century. W. Engelmann, Leipzig 1835.

- Lectures on the history of German national literature by Dr. AFC Vilmar. 2nd Edition. Elwert'sche University bookstore, Marburg / Leipzig 1847.

See also

- Literary history as a provocation of literary studies

- Reception of Persian literature in German-speaking countries

literature

- Jan Dirk Müller: History of literature / literary historiography. In: Knowledge of literature. Theories, concepts, methods of literary studies. ed. v. D. Harth and P. Gebhardt. Stuttgart 1983, pp. 195-227. (2nd edition 1989)

- Michael S. Batts: A History of Histories of German Literature. (= Canadian Studies in German Language and Literature, 37) New York / Bern / Frankfurt a. M. / Paris 1987.

- Jürgen Fohrmann: Project of the German literary history. Formation and failure of a national poetry historiography between humanism and the German Empire. Stuttgart 1989.

- Olaf Simons: Marteau's Europe or The Novel Before It Became Literature. Amsterdam / Atlanta 2001, pp. 85-94 and pp. 115-193.

History of literature in German lessons

- Hermann Korte: A difficult business. On dealing with literary history in school. In: German lessons. 6 (2003), pp. 2-10.

Web links

Single receipts

- ↑ Archived copy ( Memento of the original from May 3, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.