Delarivier Manley

Mary Delarivier (first name variants are Delariviere , Delarivière or de la Rivière ) Manley (* probably 1663 in Jersey , possibly also at sea between Jersey and Guernsey ; † July 11, 1724 , London) was an English author. She gained international fame in the early 18th century through extensive production of romaneses and journalistic articles.

Life

Most of the information about Delarivier Manley is derived from her scandalously autobiographical statements and can therefore no longer be completely objectified. First of all, the insertions she made with “Delia's story” in her New Atalantis (London J. Morphew, 1709) should be mentioned here, and secondly, openly offered as the biography of the author of the Atalantis , her Adventures of Rivella (London: E. Curll , 1714). The preface written by Edmund Curll to the first posthumous edition of Rivella from 1725 provides important subsequent information on the publication history of Rivella . According to this information, it is assumed that Delarivier Manley on the island of Jersey, possibly also at sea between Jersey and Guernsey, as the third of the six children of Sir Roger Manley († 1687) was born. The father was a royalist, an army officer, interested in history. The mother, Mary Catherine [?] († 1675), came from the Spanish Netherlands , today's Belgium. Roger Manley was stationed in 1667 under Sir Thomas Morgan as military governor and commanding the royal fortifications in Jersey; Delarivier apparently received her first name in a form of honor to Delariviere Cholmondoley Morgan, the superior's wife.

Upbringing and youth

The father's professional position brought with it a childhood with changes of location. In November 1672 Roger Manley was appointed captain of the royal regiment at Windsor. Station changes followed with the London Borough of Tower Hamlets , Brussels , Portsmouth , and Landguard Fort in Suffolk , where Roger, now widowed, was installed as governor in February 1680.

Manley himself reports of a domestic upbringing, a first great love for the actor and playwright James Carlisle, whose regiment was stationed at Landguard Fort in 1685. Together with her brother, in order to gain some distance from the feelings, she was housed with a French Huguenot family, where she claims to have obtained her French. According to her own statements, she temporarily had the chance to become lady-in-waiting to Maria Beatrice d'Este , Queen of Modena, who had to leave England in a hurry in 1687.

The family broke up in the same years. Manley's father died in March 1687. He left the daughter a fortune of £ 200 and current estate income. Edward Lloyd of her brothers had already died in 1687. Two brothers survived the father: Edward, he died in 1688 and Francis, he died at sea in June 1693. The eldest sister, Mary Elizabeth, married a captain, Francis Braithewaite. The other sister, Cornelia, came with Delarivier Manley under the tutelage of their cousin John Manley (1654-1713).

John Manley, a member of parliament with a Tory affiliation, married Anne Grosse, a wealthy heiress from Cornwall, in Westminster Abbey on January 19, 1679. Delarivier Manley asserts in her novels that she did not learn so much about the private situation. The guardian allegedly succeeded in binding her to him with a marriage vow, a union that resulted in a son, John Manley, who was born on June 24, 1691, and in the parish of St Martin-in on July 13th -the-Fields was baptized. The baptismal register shows him as the son of "John and Dela Manley". The relationship is of greater importance, since several of the traditional autobiographical statements apply to it with the assumption that Delarivier did not knowingly enter into bigamy. The separation took place in 1694, the reasons are also unclear here.

Delarivier Manley found employment in the wake of Barbara Villiers, 1st Duchess of Cleveland , the most influential of Charles II 's maitresses . Manley's employment ended after just six months on charges that she had entered into a relationship with the Duchess' son.

Writing career

The years 1694 to 1696 were associated with travel to the south west of England. With The Lost Lover, or, The Jealous Husband (1696) Manley presented her first play at the end of this time, as far as can be seen there was also a temporary reconciliation with her husband, John Manley.

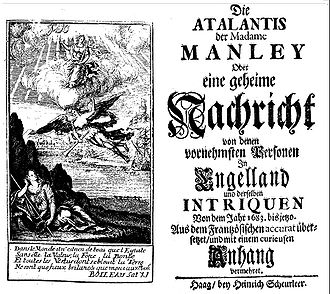

By the early 18th century, Delarivier Manley's position as an author consolidated. She won party protection and wrote consistently scandalously against the incumbent Whig politicians until her death . Her Secret Memoirs and Manners of Several Persons of Quality of Both Sexes, from the New Atlantis, an Island in the Mediterranean (1709), which alone were not a report of the fairytale island of Atalantis, became a groundbreaking success . In the two volumes the author panted through several dozen Whig politicians in novellas and shorter statements, above all John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough , the incumbent Generalissimo of the British land forces in the War of the Spanish Succession . She clings to him that she had made a career at court through the mistress of Charles II, but then got rid of it in a cold intrigue in order to be able to marry unabashedly.

The Atalantis became an instant market success and the author was summoned for questioning in preparation for a defamation process. She had only written one novel, was her famous excuse. If the incumbent Whigs were to prove to her that the stories referred were not inventions, they would have to risk it. The official charge was subsequently not made. The author added a second volume after the first, to which she added the two volumes of the Memoirs of Europe (1710) every six months , which built a new framework fiction, but were listed as volumes three and four of the Atalantis during his lifetime.

Manley expanded her field of work as a co-author of the examiner , on which Jonathan Swift also wrote. Her autobiographical Adventures of Rivella found an involuntary inspiration: Edmund Curll secretly let her know that Charles Gildon had offered him a scandalous biography dedicated to her person. She herself had disclosed parts of her past in the Atalantis (1709) on the "History of Delia". With regard to the book that Gildon had planned, one can at best assume that it might have been the same as his account of Daniel Defoe , which appeared four years later . Delarivier Manley and Charles Gildon agreed to submit an autobiography by the deadline. The Adventures of Rivella make her the object of desire of a young French man who travels to England only to have sex with her, whose novels he read translated into French. Sir Charles Lovemore, an older, rejected male friend of the author, offers himself to the young Frenchman as the first point of contact and advocate. In the preliminary talk, he tries to make the author attractive, according to the Frenchman's request. The report recapitulates all the scandals against the Manley and puts them in a better light.

Between 1714 and 1720 the Atalantis and the Rivella appeared in several editions, in the course of which the author left her pseudonym herself and on the title pages of “Mrs. Manley ”, the scandal writer known throughout Europe. 1720 followed in an adaptation of William Painter Clarke's The Power of Love in Seven Novels .

reception

Manley struggled in several personal scandals throughout her life. She fell out with Richard Steele on a financial matter, and her own illegitimate marriage was accused of bigamy. Constructively, she dealt with the reputation of being repulsively corpulent. Her own ability to create love scenes offered the literary counterbalance to the beauty of her soul.

As late as 1714, Alexander Pope scoffed at the fact that some things in the world would last as long as one read the Atalantis . Her books saw new editions up until the 1730s.

The gradual revision of their position began in the middle of the 18th century. The economic form of existence of the political scandal writer became inadmissible. Defamations of her person and her books run through the rare statements that were devoted to her until 1968. The last negative opinion came in 1969 with John J. Richetti's Popular Fiction before Richardson. Narrative Patterns 1700-1739 .

Research into her work, which is still current, began in the 1970s. The work edition, which Patricia Köster presented to specialist libraries in 1974 as a photomechanical reprint of the original editions, paved the way. Rosalind Ballaster supplemented it in the 1990s with a newly set annotated edition of Atalantis , which finally appeared as a Penguin paperback and which Manley declared a protofeminist. The verdict at this point was similar by Janett Todd and Catharine Gallagher. Fidelis Morgan started with A Woman of No Character. An Autobiography of Mrs. Manley (London, 1986) proposes the first compilation of known biographical information.

In 2001, with Olaf Simons' review of the corpus of the Atalantic novels written by Manley and imitating them, the Secret History of Queen Zarah (1705) was no longer part of the complex of works. Patricia Köster had already expressed doubts about the attribution in her edition, but retained the text. In 2004, J. Alan Downie risked speculating about the probable authorship of Joseph Browne.

The current state of research is that Delarivier Manley was the most important author in the field of fictional prose between Aphra Behn and Daniel Defoe . She was instrumental in establishing female authorship as an economic form of existence on the English market.

Remarks

- ↑ mostly stated, 1670 is probably the latest possible date

- ^ Delarivier Manley, Secret Memoirs and Manners of Several Persons of Quality, of Both Sexes. From the New Atalantis vol. 2 (London: J. Morphew, 1709), p.181 ff.

- ↑ See the Internet edition at http://www.pierre-marteau.com

- ↑ See http://pierre-marteau.com .

- ↑ Sir Roger Manley was the second son of Cornelius Manley of Erbistock. One of his brothers, Sir Francis Manley, shared the political position with him, another John Manley, on the other hand, was a major in Parliament's Army during the Civil War.

- ↑ Reproduced in her Rivella (1714), p. 113. www.pierre-marteau.com

- ↑ The Life and Strange Surprizing Adventures of Mr. D –––– De F–– (London: J. Roberts, 1719).

- ↑ See his "Rape of the Lock" in Miscellaneous poems and translations. By several hands (London: Bernard Lintott, 1712), p.363.

- ↑ The last edition of their Rivella was the first posthumous from 1725, the seventh edition of the Atalantis appeared in 1736 (London: J. Watson, 1736).

- ↑ Olaf Simons, Marteaus Europa or The Roman Before It Became Literature (Amsterdam / Atlanta: Rodopi, 2001), pp.173-179, 218-246.

- ^ J. Alan Downie, "What if Delarivier Manley Did Not Write The Secret History of Queen Zarah?", The Library (2004) 5 (3): 247-264 [1] .

Works

- Letters written by Mrs Manley (1696)

- The Lost Lover or The Jealous Husband (1696), a comedy

- The Royal Mischief (1696), a tragedy

- Almyna, or the Arabian Vow (1707), a tragedy

- Secret Memoirs and Manners of Several Persons of Quality of Both Sexes, from the new Atlantis, an island in the Mediterranean (1709), a satire in which great liberties were taken with Whig notables

- Memoirs of Europe towards the Close of the Eighth Century. Written by Eginardus (1710)

- The Adventures of Rivella, or the History of the Author of The New Atalantis (1714)

- Delarivier Manley, editor of William Painter Clarke, The Power of Love in Seven Novels (London: J. Barber / J. Morphew, 1720).

- Co-author of Jonathan Swift's Examiner .

literature

- Paul Bunyan Anderson, "Delariviere Manley's Prose Fiction," Philological Quarterley , 13 (1934), pp.168-88.

- Rosalind Ballaster, "Introduction" to: Manley, Delariviere, New Atalantis, ed. R. Ballaster (London, 1992), pv-xxi.

- Paul Bunyan Anderson, "Mistress Delarivière Manley's Biography," Modern Philology , 33 (1936), pp.261-78.

- Gwendolyn Needham, "Mary de la Rivière Manley, Tory Defender", Huntington Library Quarterley , 12 (1948/49), pp. 255-89.

- Gwendolyn Needham, "Mrs. Manley. An Eighteenth-Century Wife of Bath," Huntington Library Quarterley , 14 (1950/51), pp.259-85.

- Patricia Köster, "Delariviere Manley and the DNB. A Cautionary Tale about Following Black Sheep with a Challenge to Catalogers," Eighteenth-Century Live , 3 (1977), pp.106-11.

- Fidelis Morgan, A Woman of No Character. An Autobiography of Mrs. Manley (London, 1986).

- Dale Spender, entry in Mothers of the Novel (1986).

- Janet Todd, "Life after Sex: The Fictional Autobiography of Delarivier Manley," Women's Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal , 15 (1988), pp. 43-55.

- Janet Todd (ed.), "Manley, Delarivier." British Women Writers: A Critical Reference Guide . London: Routledge, 1989. 436-440.

- Catharine Gallagher, "Political Crimes and Fictional Alibis. The Case of Delarivier Manley," Eighteenth Century Studies , 23 (1990), pp. 502-21.

- Olaf Simons, Marteau's Europe or The Novel Before It Became Literature (Amsterdam / Atlanta: Rodopi, 2001), pp.173-179, 218-246.

- Ros Ballaster, 'Manley, Delarivier (c.1670–1724)' , Oxford Dictionary of National Biography , Oxford University Press, 2004.

- J. Alan Downie, "What if Delarivier Manley Did Not Write The Secret History of Queen Zarah?", The Library (2004) 5 (3): 247-264 [2] .

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Manley, Delarivier |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Manley, Delariviere; Manley, Delarivière; Manley, de la Rivière |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | English author |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1663 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | jersey |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 11, 1724 |

| Place of death | London |