Reception of Persian literature in German-speaking countries

The reception of Persian literature in German-speaking countries is of great importance for literature. This concerns the knowledge of the worldview of Persian poets as well as their poetic procedures.

The late Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, for example, recognized and valued the skeptical mobility that is expressed in Persian poetry. Almost two hundred years earlier, in the first half of the 17th century, there were first translations of Persian literature into German, initially with French as the intermediary language. When Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall began his famous translations of poetry in Istanbul in 1799, Persian was barely available for translation.

In addition to pure translations, bilingual editions are occasionally produced. The first is the partial edition of Nezāmi's Seven Beauties (around 1200), which Franz Erdmann published in Kazan ( Tatarstan , Russia) in 1843 and the second edition of which also appeared in Berlin the following year.

Persian literature has also been received directly by authors with Persian mother tongue who live and publish in German-speaking countries since the middle of the 20th century.

Ottoman advance since the 15th century

Between 1481 and 1566, many Arabic and Persian works were translated into Turkish. In the 1630s, the Ottoman began polymath Katib Çelebi in transit in Syrian Aleppo the title of manuscripts to grasp that he found in local antique shops, and thus began his comprehensive project: approximately 14,500 works in Arabic, Persian and Turkish language of science and literature to be described in alphabetical order (in Arabic, Kašf aẓ-Ẓunūn ʿan Asāmī al-Kutub va-l-Funūn ;كشف الظنون عن أسامي الكتب والفنون). This bibliographic lexicon became the basis for Barthélemy d'Herbelot de Molainville's Bibliothéque Orientale (1697), which was translated into German by J. Chr. F. Schulz between 1777 and 1779, including additions by JJ Reiske and HA Schultens and in the years It was published in Halle from 1785 to 1790 with the title Oriental Library or Universal Dictionary, which contains everything that is necessary for knowledge of the Orient .

Persian manuscripts in European libraries before 1700

In the middle of the 17th century, the University of Leiden (NL) began to compile a Persian manuscript collection. From there, Jacobus Golius left for the Orient between 1625 and 1629 to study and buy manuscripts. Oriental manuscripts were later bought for the Bibliothèque Royale in Paris and for the Bodleian Library in Oxford . There was no comparable center in German countries, but there were some manuscripts in private libraries of scholars in Munich, Berlin, Hamburg and Dresden. From the late 17th century onwards, oriental studies in Europe had been in decline. After Leiden, Johann Jakob Reiske also set out from Leipzig in 1738 to improve his language skills.

Prints in Persian before 1700

The first wooden letters for Arabic characters were cut in Vienna as early as 1554 , because there was an interest in the practical use of oriental languages. In addition to Vienna, 1651 types were used in Amsterdam for printing Saadis Golestan and were preserved until at least 1882 when they were used again for printing another work in the Netherlands.

Thesaurus Linguarum Orientalium (1680–1687)

In 1653 Franz von Mesgnien Meninski (1620 / 1623–1698), who later became Emperor Leopold I's first interpreter , went to Constantinople with the Polish embassy and wrote his Thesaurus Linguarum Orientalium Turcicae, Arabicae, Persicae ... , the Persian loan words im Turkish listed and printed in four volumes 1680–1687 in Vienna, also contained translations into German (in addition to Latin, Italian, French and Polish).

17th century

In the early baroque period, Martin Opitz , among others, in his book von der Deutschen Poeterey (1624), regarded a thorough knowledge of poetry in Latin and Greek as a prerequisite for being able to poetry in German. Opitz recognized the importance of translation "in order to lay the foundations for the German language." With the translation and reception of Persian literature, further works reached the horizon of his contemporaries who were active in language creation.

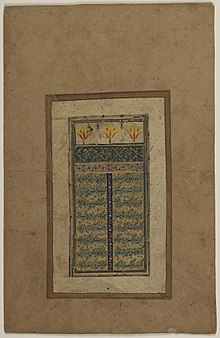

Saadis Golestān (1636 or 1654, Persian Rosenthal )

The first literary work in Persian to become known in Europe is the collection of stories and poems Golestān by Saadi from 1258. It was first published in French in 1634 and then in German in 1636. As early as 1654 a version, translated directly from Persian, appeared, the title of which announces a lot of funny histories, astute speeches and useful rules of the poet Shich Saadi from 400 years ago and which is written in strong metaphorical language. In the translation it becomes clear that there is an interest in the poet's worldview. It comes from Adam Olearius , who began to learn the language in Persia in 1637 and wrote the work after his return in cooperation with the Persian ambassador Ḥaq (q) wirdī, who lived with him and named Olearius' support in the title of his work. This translation was published in further editions in 1660, 1663, 1671 and 1696 and served as a literary inspiration for Andreas Gryphius ( Catharina of Georgia , 1655, printed 1657) and Daniel Caspar von Lohenstein ( Ibrahim Bassa and Ibrahim Sultan ) from the middle of the same century , 1673) and by Hans Jakob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen ( Simplicius Simplicissimus , 1668). Grimmelshausen's early manuscript Keuscher Joseph contains a competition in lemon peeling with sharp knives between Potiphar's wife and her friends. The material comes from the second edition of Olearius' Golestān translation, which appeared in 1660. The work was imitated in German in 1679 by Samuel von Butschky, not just in terms of content, but also formally .

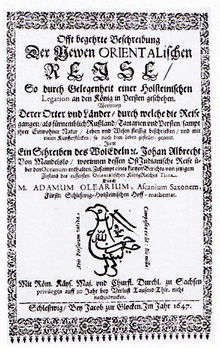

Adam Olearius' travelogue (1647, 1656, 1663 etc.)

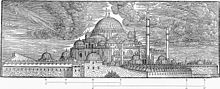

In the years 1635 to 1639 a trade expedition of the Schleswig-Holstein embassy of Friedrich III. about Russia to the Persian court in Isfahan , whose travel description by Adam Olearius, Moskowitische und Persische Reise (first 1647, extended to the final version in 1656) is a learned proto-ethnography, which is considered the first scientific travel description. Already a bestseller in German-speaking countries during Olearius' lifetime (until 1671) - not least due to skillful work with text and image material - it was the only non-religious work in the 17th century that was translated into other languages (French, English, Dutch, Italian ) has been translated. Among other things, it left traces in Montesquieu's work Persian Letters (1721).

Olearius dealt with facts quite freely - as Barbara Becker-Cantarino concluded in 1981 from the contents of several rediscovered letter autographs by fellow traveler Paul Fleming. With Olearius the new concept of experience is developed for the first time, with which other regions in their diversity and ambiguity can be traveled and described as external worlds. From this time onwards, travelers did not regard their experiences as merely threatening counterworlds, but were "overwhelmed and impressed by the wealth and temptations, by the diversity of experiences abroad", says Michael Harbsmeier in 1994. Elio Brancaforte worked out in 2003, that the travelogue has a principally Eurocentric perspective.

The fifth chapter contains The 24th Chapter. From the Persian language and writing and the 25th chapter. From the Persian Academies, and freyen Künsten , in which the role of meaningful verses in everyday life is reported and that people like to read Saadi's “Külustan” above all “because of the delicate language”. This is followed by Chapter 26. History of Alexander, based on a Persian description, and of two brothers Chidder and Ellias, and then Olearius brings up literature.

Of their poets and their verses (Part V, Chapter 27)

In the 27th chapter, “Of their poets and their verses”, it says: In Persia, poetry is loved more than probably nowhere else. It is not only to be found in written form, but is occasionally very present “also in person, bey For gentlemen in Gastereyen, also on the Maidanen, in jugs and other feasts ”, but also as money-making in the home of the wealthy for the amusement of guests. Poets at the king's and at other courts, where they do not mix with the people but only work inside the house, are in some cases very much admired for their creative power. Those who can write poetry can be recognized by their clothes on the street and carry a bag for books, paper and an inkwell so that they can write a new poem for customers if necessary. In the market, poets also read their poems, which often target the Turks and their saints. There are great qualitative differences in poetry and those who could not call themselves poets adorn themselves with foreign feathers in the pubs and in the market in order to be paid for by the people. Old poets are read “as much in Turkish as in Persian. Because both languages are equally valid for them, ”both would like to read. “Your best poets, however, that you have in writing” are according to his information: Saadi , Hafis , Firdausi , Füssuli , Chagani , Eheli , Schems , Nawai , Schahidi , Ferahsed , Deheki , Nessimi and others. Olearius briefly explains that Persian verses have rhymes as in German, even if it is not taken so strictly if there is one more or less syllable per verse. Internal rhymes and word repetitions, especially anadiplosis , are also used according to certain rules . One takes pleasure in the ambiguous use of words. This is followed by the examples of a quatrain in Persian, in Latin transcription and underneath in German translation, as well as a two-line in Turkish with Latin transcription and German translation. Under the same heading there is a brief discussion of law and medicine.

Poems by Paul Fleming as part of the travelogue

At the age of 24, the poet and medical student Paul Fleming applied to participate in this trip on advice from Olearius. His degree in the arts and philosophy had been brought about in May 1633 (with Olearius as one of his examiners) after the exams in January of that year were canceled because of the war and the plague in Leipzig. He interrupted his medical studies.

Adam Olearius posthumously added fifteen poems by his travel companion and already famous poet Paul Fleming to the travelogue and some of them were placed in the Persian part of the trip and in the part of the return trip, respectively. Hans-Georg Kemper has explained that Olearius was able to incorporate Fleming's occasional poetry well into the travel description because Fleming had redesigned the opportunity for a community experience. In this way they are presented as glamorous highlights of the tour group experience.

Olearius had published many of the other poems written on the trip in Fleming's posthumous collection Teütsche Poemata (ready for printing in 1642, not published until 1646), to which a connection is made in the travel description. On the other hand, the dedication of the fifth book of Fleming's Oden to the “particularly familiar” travel companion Johann Albrecht von Mandelslo makes a reference to the trip or its description clear.

Fleming's poems make up the largest part of the fact that, beyond the empirically observable, a meaningful level becomes perceptible in the travel report, on which Olearius can show why he and his friend Fleming joined the journey without this having to be said directly, Harald Tausch said in a contribution from 2012. Various strategies of secrecy interlock intertextually, which are also literarily productive because they are only hinted at. What is to be reported is to be interpreted in retrospect with the help of a camouflage technique: only those who were familiar with certain signal words of the alchemical tradition could recognize the actual motive why Fleming wanted to join the trip: more about the galenic medical knowledge available in Persia to find out - which was no longer possible with trips to Spain or Sicily because of the spiritual devastation caused by the Inquisition in order to be able to combat the infectious diseases plague and syphilis , which were rampant at home (Fleming obtained his doctorate on the latter after his return to the University of Leiden). During these years counter-Reformation campaigns were carried out in Central Europe against iatrochemists, so that Fleming could have consciously or unconsciously viewed the trip as an evasive maneuver.

Paul Fleming's poetry (1642/1646)

Fleming was one of the trip the group of Hofjunker and Steward to. With Fleming dying at the age of 30 nine months after his return, Fleming had spent most of his adult years traveling. Most of his works were created during this time.

In 2012, Harald Tausch analyzed some of the Fleming odes arranged by Olearius and published in 1646 shortly before the travelogue and came to the conclusion “that Fleming does indeed take up the Petrarchist motif tradition, but at first glance injects strange, erratic words into it secretly refer to the imagery of alchemy. "

150 years later, in his lectures on the history of romantic literature (1803/1804) , the romantic August Wilhelm Schlegel praised Fleming's poetry, in addition to “blooming imagination, enthusiasm, abundance and youthful vigor” as well as the “glowing colors of his pictures” - in summary: "He had a German heart and an oriental fantasy" and had "understood his trip with a romantic sense and presented it wonderfully."

180 years later, however, Fleming's biographer Heinz Entner hardly seems to find anything of this kind when he formulated in 1989: “Anyone looking for the charm of exotic experiences will be disappointed to find that the poems only hint at and convey hardly anything” and “The poetic The yield of these texts [remains] meager if one looks for the direct reflection of external travel impressions. "

Saadis Bustan in German (1696)

From Bustān , Saadi's lyrical work, there were some maxims in 1644 in a bilingual edition Persian-Latin by Levinus Warner (1619-1665) and a Latin translation, which was intended as a complete edition, was published in 1651 by George Gentius . In 1688 a Dutch prose translation by Daniel Havart followed. The title of the first version in German, which is based on this Dutch prose version, is Der Persianischer Baum-Garten: Planted with unreadable props of many stories, strange incidents, instructive histories and remarkable sayings . The editors of a posthumous edition with works by Adam Olearius and others (1696, enclosed Persian rose valley and tree garden ) call this translation into German their own work.

18th century

Reception example: Turandot fabric (from 1710 first in French)

The history of reception can be sketched out using the Turandot material. Nezami's story What the Russian princess told on Tuesday in the red dome of Mars , the fourth evening in his poem Haft Paykar ( The Seven Beauties , 1197), was considered by Rudolf Gelpke in 1960 to be the oldest documented Persian version. However, Nezāmi does not mention the Persian name Turandocht and the story has a Russian setting. Fritz Meier wrote in 1941: “Niẓâmî does not work out a fate or a tragedy. His aspect is the preciousness , the preciousness of the material, the thoughts and the language (...) a sublime meaning transfigures the drastic. "

1710–1712, François Pétis de la Croix had published the collection of stories A Thousand and One Days in five volumes on behalf of Marie-Adélaïde de Savoie as a result of the French adaptation of A Thousand and One Nights by Antoine Gallands (1704) , declared as Persian fairy tales. A thousand and one days , in contrast to a thousand and one nights, were arranged in such a way that the focus was on the figure of a princess unwilling to marry, whose wet nurse tells her pleasant stories about men in order to make them more favorable to them. De la Croix's Turandot story bears the title “Story of Prince Khalaf and the Princess of China.” Carlo Gozzi obtained the narrative framework for his tragic comedy Turandot (1762), of which Friedrich Schiller was in a prose version in 1801 set to work on his eponymous piece , also with a Chinese setting. If Turandot is characterized by Gozzi as capricious and obdurate, Schiller lets her attempt to dissuade the prince in order to advertise her, which suggests rather noble motifs. Theodor Körner commented on Schiller's work with a view to the opera genre. In fact, thirty years before Gozzi's play, a Turandot opera, La Princesa Chine (1729), had premiered by Jean-Claude Gillier and Alain-René Lesage . In 1809 Carl Maria von Weber wrote incidental music for Schiller's piece and the Turandot material was then more likely to be received on the opera stage, for example through Giacomo Puccini's Turandot (1926).

From 1754 Oriental Academy in Vienna

Around the middle of the 18th century, as the Christian theological influence declined in the Enlightenment and the influence of the French Encyclopédie (1751–1780) rose in German-speaking countries , interest in religious tolerance, aesthetics and growth grew the autonomy of the imagination - as can be found in Saadi, for example. Maria Theresa's economic interests also grew in the southeast, whereupon the Imperial-Royal Academy for Oriental Languages was founded in Vienna in 1754 .

1771 Ghazel; Roman-like idealization of a Persian ruler

In 1771 the first European translation of Persian poetry in the form of the Ghazel appeared , a form previously unknown that was to have a great impact in German-language poetry. The poems by the Austro-Hungarian Ambassador in London and Berlin, Graf were published in Latin Karol Reviczky (1737-1793), whose work Specimen Poeseos Persicae next to poems from the Diwan of the poet Hafiz also contained a highly regarded history of Persian poetry.

In the late summer of 1771 Albrecht von Haller published a state novel with the title Usong. An oriental story about a ruler in Persia at the end of the 15th century, whom Haller idealized as a good-natured, enlightened despot. This is important for the German image of Persia at that time.

Herder's re-seals

In the literary discovery of the Orient with his own works in German, Johann Gottfried Herder was decisive, even if he has an ethnically polarizing tone that is suspect from today's perspective. Herder turned away from French culture, said that he could not find any role models among the Greeks and Romans and set out in the East to search for the origin of all being by studying, among other things, the oriental languages and Persian poetry, but without considering a trip to Persia. Herder was already enthusiastic about Saadi as a youth and undertook changes in poetry.

English literature had been "discovered" since the 1740s and Herder also used works by the British translator William "Orientalist" Jones (1774/1777) for his flowers collected from oriental poets (1792 ). In 1787 Herder had come forward with speculations about Persepolis in the third collection of his Scattered Leaves .

19th century

Translations by Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall

Nezami

In 1809 the translator Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, a graduate of the Vienna Oriental Academy , published the first revisions by Nezāmis Chosrau and Schirin as a book, which had been published in Christoph Martin Wieland's Neuer Teutscher Merkur since 1798 .

Hafez

1812–1813 followed, "translated from Persian for the first time in full", with the Diwan des Hafis ( DMG Ḥāfiẓ, died around 1389), the first complete translation of a divan edition into a European language, also by Hammer-Purgstall, who was responsible for the work Started in Istanbul in 1799. At this point in time, there was hardly any translation into Persian. Perhaps the greatest achievement is that Hammer-Purgstall broke away from the ethnically polarizing tone of Herder. Hafis was first mentioned by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in 1814. The anecdotal foreword in Hammer-Purgstall's Hafis-Diwan could have been just as significant for Goethe's late collection of poems West-Eastern Divan (1819), his homage to Hafis, as the translated poetry. In 1818 Hammer-Purgstall wrote in the dedication of his orientalizing poems Morgendländisches Kleeblatt : “The magician's tools”, and he meant Goethe, whom he did not know personally.

Chayyam

Hammer-Purgstalls Study of the History of the Fine Oratory Arts of Persia. A Bluethenlese from two hundred Persian poets (1818) also proved to be influential for German-language literature. Goethe used them for his notes and treatises , which complement the poems of his West-Eastern divan . However, Goethe did not mention the 25 Robāʿīyāt by Omar Chayyām (11th century), which were first published as part of the Blüthenlese translated into a modern Western language, also by Hammer-Purgstall.

Rumi

Hammer-Purgstall dedicates a long and enthusiastic section to Rumi in his History of the Fine Speech Arts of Persia (1818). It was not until 1849 that Georg Rosen was supposed to translate the first parts of Rumis Masnawī into German verse.

Extensive importance of translations

Without Hammer-Purgstall's translation of Hafis into German, there would have been no enrichment of their poetic repertoire for either Friedrich Rückert or August von Platen , Emanuel Geibel , Paul Heyse , Theodor Storm or Heinrich Heine, except for Goethe, after Hafis suggested it. Rückert's free adaptations as well as the more rigorous translations he wrote afterwards had a great influence on many, including epigonal, German-speaking poets of the 19th century. In Hugo von Hofmannsthal's early work (1891) there are some ghasels of great beauty.

Goethe's late work West-Eastern Divan (1819)

From Goethe's point of view, one of the main characteristics of Persian poetry is its skeptical mobility. In his experiment of strangeness in the collection of poems West-Eastern Divan (1819), in addition to motivic and metrical aspects, stylistic adaptations to Eastern poetry can be recognized, for example through the use of paranomasia , which Hendrik Birus described as "characteristic of Goethe's emerging orientalizing style" is called: for example "Liebchens / Liedchens" and "Heilig / Secret" in the poem Allleben or in talismans the combination "confuse" / "to err" / "unravel". A reconstruction of the textual sources used as inspiration in the opening poem of the first book, Hegire , revealed that there were four different ones, and this poem is considered a typical example of Goethe's poetic process. Goethe's aesthetic concept is characterized by a creative interaction of orientalistic space of meaning and individual strategies of poetic action and moves in the field of tension between the familiar and the unfamiliar in a sphere of understanding. For the late Goethe, the oriental realms meant a virtual asylum search in times of an impending collapse of his own country (Napoleonic wars, beginning of the restoration instead of the social awakening with the help of the ideals of the French Revolution).

At the Humboldt Kolleg in Graz in 2006, Manfred Osten commented on the broad impact of the work : “At the beginning of the 20th century, thousands of returns from the West-Eastern Divan were lying in the attic of the Cottas publishing house - in spirit they are still there today. Because Goethe's insights into our helplessness and speechlessness towards Islam still receive hardly any attention. ”Anil Bhatti, in turn, stated in 2007 that with West-Eastern Divan “ the title of a poetic work has become a signal for a cultural-political program ”.

Friedrich Rückert

In contrast to Goethe, Friedrich Rückert had a knowledge of Persian and after a visit to Hammer-Purgstall in 1818 he began translating. He dealt with the Ghazel at Jalāl ad-Dīn ar-Rūmī (1819) and Hafis from a German-speaking perspective. In 1821 Rückert announced "Persica" (Eastern Roses) to his publisher Johann Friedrich Cotta and explained that these would differ from Goethe's poems in that the main thing was form rather than spirit. Rückert proceeded in such a way that he tried to recreate the formal form of the oriental original in German, in perfectionist re-poems that sound like a corset compared to Hammer-Purgstall's style and whose arbitrariness is only more cleverly camouflaged. The similarity between Goethe and Rückert lies in the fact that both of them often turn a single Hafez verse into a poem. In turn, Rückert's works differ from Hammer-Purgstall in that the latter chose inconsistent distiches or sometimes quatrains, while the latter, on the other hand, chose stanzas from double verses with identical rhyming words in the second line. In German, as in Persian, it is not possible to always rhyme on identical syllables, so Rückert created this intermediate path. In other words: Hammer-Purgstall “leads Hafis into German, instead of the German to Hafis like Rückert.” The cycle of life, which Rückert found impressively depicted in Persian poetry as a contemplative circulation around a center, seemed to him in the form of the Ghazel to be best expressible with the rhymes aa, ba, ca etc.

From 1827 Rückert published his translation of an Indo-Persian work on rhetoric and poetry in the magazine Fundgruben des Orients , which Hammer-Purgstall published in Vienna. Half a century later published as a book under the title Grammar, Poetics and Rhetoric of the Persians from the seventh volume of the Ḱolzum booklet (1874) by Wilhelm Pertsch , it is now regarded as a fundamental work on Persian poetry. Rückert describes and explains in this work which building blocks have to be considered in intercultural communication processes of Persian poetry. Rückert was one of the very productive German-speaking literary translators and translated almost all of the larger works of Persian (and Arabic) poetry that were available at the time into German.

Rückert's understanding of Rumi

As a poetic translator, Friedrich Rückert wanted to gain such an in-depth understanding of Persian poetry that nothing foreign remained. He was convinced that there is a cross-national human spirit. Rückert's adaptations and recreations from the Mas̱nawī-e ma'nawī ("two-line of spiritualization") of Rumi show how he understood the spiritual-mystical aspect of the statements of the Sufi master and transferred it to German-speaking readers.

- az ǧamādī mordam-o nāmī šodam

- w'az namā mordam be-ḥeywān bar-zadam

- mordam az ḥeywānī-o ādam šodam

- pas če tarsam key ze mordan came šodam

- ḥamle-ye dīgar be-mīram az bašar

- tā bar-āram az malā'ek par-o sar

- bār-e dīgar az malak qorbān šawam

- ānč 'andar wahm na-āyad ān šawam

This poem is written in a metalanguage, which can hardly be seen from Rückert's adaptation; but he understood and interpreted this poem in the sense of Sufi mysticism :

- 1st double verse:

- This is not a concrete stone , but its basic substance, the mineral ( ǧamād جماد).

- The plant is to be interpreted as "something that grows" ( nāmī نامى or namā نما).

- And the animal is "something that lives = is animated" ( ḥeywān حيوان).

- Thus, this double verse could also be interpreted as meaning that “I” became matter from energy, now died as such and grew until “I” finally awoke to (animate) life.

- 2nd double verse:

- And out of that "I" became a clod of earth breathed by God , arab. - Pers. ādam (آدم), which goes back to the Hebrew adam and means formed from the earth (= earthling).

- 3rd double verse:

- Therefore Rumi also uses the term bašar (بشر) = human race , which emerged from this Ādam . And the angels are spirit beings that ultimately still have shape.

- 4th double verse:

- This figure must also be sacrificed so that “I” become an aeon . This aeon , arab. ān (آن), is to be equated with eternity, but also with the tiny moment ("Nu") which the mystic strives towards and which should not be just a mere deception - it can be equated with extinction in God , arab. al-fanā ' (الفناء), as a breath of God, to be equated again with pure energy that merges in the eternal cosmic (divine) energy.

Rückert's understanding of Hafez

How Friedrich Rückert recorded the Persian poet Hafis , he wrote in his poetic diary around 1860:

Hafis, where he seems to

only speak supersensible, talks about sensual things;

Or

does he only speak supernatural when he seems to be talking about the sensual?

His secret is insensible,

because his sensuality is supersensible.

August von Platen

August von Platen , who also had some knowledge of Persian, illustrated the complex structure and depth of Hafiz's poetry in his reproductions from the Diwan des Hafis, which were published in the 1820s. Platen's aim was to recreate Hafez's poetry in German, thereby helping to make Persian verse forms fruitful in the German language.

Heinrich Heine

Heinrich Heine was the most important contemporary recipient of Goethe's Divan . He is considered to be “the great exception to the Divan appreciation” by praising the sensualism in Goethe's collection of poems, which Hafis celebrated in Goethe's view by making the rigorous dogmatism of the Koran flexible and humanizing as a poet. Heine implemented Goethe's self-irony with regard to the logocentric dogmatic tendencies of a Eurocentric teaching society, which again prevail in the West, in his Romanzero poems. In it, Heine expands Goethe's sensualism into the global, "by prescribing a sensual upbringing for the freezing lean spiritualism in the sense of a comprehensive perception of reality."

With his stylistic devices, Heine was able to reflect a broken, post-romantic view of the world. In this sense, Jan Volker Röhnert also counts the seemingly unmotivated linked images, the jumps from one subject to the next, discord, disharmonies and 'impure' tones "to the" strangeness of the original ".

Orientalizing poetry collections

From the middle of the 19th century, German literature borrowed materials and motifs from Arab-Persian poetry for light and meaningless arrangements, wrote Diethelm Balke in the Reallexikon der Deutschen Literaturgeschichte , the first volume of which appeared in 1958. It can be said that, in part, much-read orientalizing poetry collections were created, for example - the most popular work of this kind - Friedrich Bodenstedt's "hausbackene" (Schimmel) songs by Mirza Schaffy , which from 1851 onwards, including translations, achieved almost 300 editions and thus became an unusual success in bookselling.

20th century

In the literary studies of the second half of the 20th century, according to Navid Kermani, the example of Persian or Arabic literature can be used to demonstrate an exclusion mechanism “with which Europe constructs its own history.” Based on the two canonical studies by Erich Auerbach ( Mimesis , 1946) and Ernst Robert Curtius ( European literature and Latin Middle Ages , 1948), the paradigm that there is an exclusive occidental literary history is still influential in today's school lessons. Kermani argues that there are almost no non-European influences. For example, Curtius zu Dante does not mention any of the Arab forerunners, sources or contacts and the literary history of Spain does not begin in his study until the 16th century. Curtius also does not discuss the reasons for Cervantes to pass his Don Quixote off as a translation of an Arabic work.

Characteristics of German research on orientalism

At the beginning of the 1980s there was a turning point for German research into orientalism in literary and cultural studies through a combination of postcolonial movement and the linguistic turn , according to the analysis by Andrea Polaschegg (2005): Until then, orientalizing literature in German studies was based on individual Aspects or authors researched, but without a systematic evaluation, and only since then have there been increasing numbers of works that dealt with the image of the Orient in various texts by different authors against the greater cultural-historical background of European reception and influence. One began to look at a political dimension and to bring the Western reception of the Orient into connection with colonialism and imperialism - at first hesitantly in German studies. In her epistemogram of the scientific occupation with Orientalism, Polaschegg identifies two basic assumptions that concern the relationship between imagination and power, but whose different explanations are not openly debated (at least not until 2005): “The imaginary character of the Orient and the existence of some kind of connection between social constructions and power relations is now so evident that all differences in the light of this self-evident shrink to marginalia. ”At the beginning of the 1990s, a search for patterns of order and interpretation other than the political, economic or social categories continued Phase of the Cold War came and cultural factors came up, with which a new antagonism was sought in the Western discourses . In the course of this, the term Orient changed to the term Islam . According to the analysis by Polaschegg (2005), one of the unquestioned truths of research on orientalism is that in the course of the cultural turn there is an indispensable link between alterity and “ foreignness ”. The German literary and cultural studies show strong continuities and homogeneities in dealing with Orientalism, which Polaschegg attributes to the fact that in many cases Anglo-American criticism of Edward Said's Orientalism (1978) was just as little received as the corresponding debates in the German one Islamic Studies.

Reception in exile

Persian literature has also been received directly by authors with Persian mother tongue who write and publish in German-speaking countries since the middle of the 20th century. After some authors were arrested (for example, Hushang Golschiri 1996) or even murdered, writers left Iran in large numbers, and as a result exile literature became a mass phenomenon. Even in exile, in 1992 in Bonn, Fereidoun Farrokhsad, an Iranian author, was murdered by secret service agents.

21st century

Hammer-Purgstall's translation of Hafis into German was published again in 2007 for the first time in 200 years. "That we read a translation almost two hundred years old is in itself a rare case," writes Stefan Weidner in the epilogue. "We read it because the history of literature and reception has raised it to the rank of an independent work."

Persian literature is increasingly being received in German-speaking countries by authors who are able to receive Persian literature in the original, not least because they have one of the Persian language variants Fārsī , Darī , Toǰikī as their mother tongue. The 2011 lyric anthology Hier ist Iran! Persian poetry in German-speaking countries includes authors who write in Persian and / or German in German-speaking countries as well as works by authors who write in German in Iran: "The point of reference is therefore not only geography, but also language," explains the Editor his concept.

Digitized primary texts on the web

- Adam Olearius (1654): Persianischer Rosenthal: in which many funny histories, astute speeches and useful rules 400 years ago by an ingenious poet Schich Saadi described in Persian language / ietzo but by Adamo Oleario; with the addition of an old Persian name Hakwirdi, translated into High German, and adorned with many copper pieces, Holwein and Nauman, Schleszwig 1654. Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel , Wolfenbütteler Digitale Bibliothek (WDB)

- Adam Olearius (1656): Increased Newe Description of the Muscowitischen and Persischen Reyse: So happened by the opportunity of a Holstein embassy to the Russian Tsar and King in Persia; In what the opportunity of those places and countries / through which the Reyse passed / as Liffland / Russia / Tartaria / Medes and Persia / sampt the inhabitants nature / life / customs / house, world and spiritual status / carefully recorded / and with many mostly after adorned / to be located in figures placed in life. Which at the other time publishes Adam Olearius Ascanius / the Princely Governing Lords of Schleßwig Holstein Bibliothecarius and Hoff Mathematicus. (or urn ). (Note: Incorrect pagination: pp. 755–768 [i. E. 753–766]), Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel , Wolfenbütteler Digitale Bibliothek (WDB) , scope of the scan: 862 pages ([15] p., 768 [ie 766] p ., [17], [10] p., [20] f. P.: Copper., 6 portr. (Copper engr.), 20 illustrations (copper engr.) 3 ct. (Copper engr.), Numerous illustrations. (Copper engraving), ill. (Wood carving), Kt. (Copper engraving).; 2 °). Catalog entry Wolfenbütteler Digitale Bibliothek (WDB)

- Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall (1818): History of the beautiful speech arts of Persia: with a flowering from two hundred Persian poets in the German Digital Library , or ( urn ), XII, 432 pages, Heubner and Volke, Vienna 1818; Location: Munich, Bavarian State Library , Signature: 4 A.or. 2104, catalog entry Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

More research literature

- Hamid Tafazoli (2016): "On the usability of foreign journeys. Reflections on aspects of cultural writing", in: Eva Wiegmann (ed.): Interkulturelles Labor. Luxembourg in the field of tension between integration and diversification , Frankfurt a. M. et al .: Lang, 2016, pp. 157-178.

- Hamid Tafazoli (2014): "Odalisques and love slaves. The male view of women in text-light cultural mediation", in: Orbis Litterarum 69.5, pp. 355–389.

- Maḥmūd Falakī (2013): Goethe and Hafis. Understanding and misunderstanding in the interrelation of German and Persian culture Table of contents , Berlin: Schiler, ISBN 978-3-89930-404-6 .

- Titus Knäpper (2011): "Ex oriente lux": News about the oriental in the "Parzival" , in: Arthurian novel and myth , edited by Friedrich Wolfzettel, Cora Dietl and Matthias Däumer. De Gruyter, Berlin, ISBN 978-3-11-026252-0 , pp. 271-286.

- Hamid Tafazoli (2011): "Paul Fleming's travel poetry as an attempt at transcultural communication in the early modern period", in: Tarvas, Mari (ed.): Paul Fleming and the literary field of the city of Tallinn in the early modern period , Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann, Pp. 61-73.

- Hamid Tafazoli (2010): "Culture of remembrance and ancient identity patterns. Herder's mythologization of the monuments of Persepolis", in: Herder Yearbook X, pp. 83-11 (?).

- Hamid Tafazoli (2010): "Goethe's image of Persia in the West-Eastern Divan and the Sivan's poet's idea of self-reflection", in: Yearbook of the Austrian Goethe Society 111/112/113, pp. 66–84.

- Monika Schmitz-Emans (2007): “Oriental with Jean Paul”, in: Orientdiskurse in der Deutschen Literatur , edited by Klaus-Michael Bogdal, Aisthesis Verlag, Bielefeld, ISBN, pp. 81–123.

- Hamid Tafazoli (2007): The German Persia Discourse. On the scientification and literarization of the Persia image in German literature from the early modern period to the nineteenth century , Bielefeld: Aisthesis, ISBN 978-3-89528-600-1 .

- Hamid Tafazoli (2006): "'As long as it doesn't go into the absurd, you can endure it.' Ambivalences of a Goethe reception in Persia ", in: Hölter, Achim (ed.): Comparative literature. Yearbook of the German Society for General and Comparative Literature Studies , Heidelberg: Synchron, pp. 55–70.

- Andrea Polaschegg (2005): Inessential forms? The Ghazel poems by August von Platen and Friedrich Rückert: Orientalizing poetry and hermeneutic poetics , in: Poetry in the 19th century. Genre poetics as a medium of reflection in culture , edited by Steffen Martus, Stefan Scherer and Claudia Stockinger. Bern u. a., Lang, ISBN 3-03910-608-2 , pp. 271-294.

- Annemarie Schimmel (2002): “Introduction”, in: Saadi's Bostan . Translated from Persian by Friedrich Rückert. Works from the years 1850–1851. Second volume. Edited by Jörn Steinberg, Jalal Rostami Gooran, Annemarie Schummel and Peter-Arnold Mumm. Wallstein Verlag, Göttingen 2013 [sic], ISBN 978-3-8353-0495-6 , pp. 7-10.

- Faramarz Behzad (1970): Adam Olearius' "Persianischer Rosenthal": Studies on the translation of Saadi's "Golestan" in the 17th century , dissertation at the University of Göttingen / Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht , Göttingen

- Walter Hinz (1969): Persisches im ‹Parzival› , in: Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran , Neue Reihe 2/1969, pp. 177–181.

References and comments

- ↑ Paris is an old center of Iranian research and is still one of the most important centers of Iranian exile culture today. Cf. Michael Stausberg: The religion of Zarathushtra. Past - present - rituals. Volume 2, Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, 2002, ISBN 3-17-017119-4 , p. 328. Between 1800 and 1900 monographs and 475 articles on Persian poetry were published in France in 2004, and 58 monographs and 5 articles in German-speaking countries. Cf. Kambiz Djalali (2014): The foreign is one's own. The classical Persian poetry in the Franco-German area of the 19th century. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg, ISBN 978-3-8260-5159-3 , p. 468.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Stefan Weidner (2007): Poetic Inventory of the Orient. Epilogue in: Hafis: Der Diwan. From the Persian by Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall. Munich: Süddeutsche Zeitung (series of publications Bibliotheca Anna Amalia), ISBN 3-86615-415-1 , pp. 973–987.

- ↑ In this center of Russian oriental studies, a scholar with Persian roots who traveled through was won over for a position at the university in 1826, cf. David Schimmelpenninck van der Oye (2008): Mirza Kazem-Bek and the Kazan School of Russian Orientology , in: Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East , Volume 28, Number 3, 2008, pp. 443–458, p 452-453.

- ↑ a b Renate Würsch: Niẓāmīs treasure trove of secrets. An investigation into 'Maẖzan ul-asrār'. Reichert, Wiesbaden 2005, ISBN 3-89500-462-6 , p. 25 f.

- ↑ Today's example of a bilingual poetry anthology: House of World Cultures (Ed.): Persischsprachige Literatur. Das Arabische Buch, Berlin 1991, ISBN 3-923446-75-6 .

- ↑ a b Kioumars Ghereghlou (2011/2012): KAŠF AL-ẒONUN (“Unveiling of suppositions”), a major bibliographical dictionary in Arabic, composed by Kāteb Čelebi Moṣṭafā b. ʿAbd-Allāh, also known as Ḥāji Ḵalifa (1609-57) , Encyclopædia Iranica

- ↑ Orhan Şaik Gökyay: Kâtib Çelebi. (pdf) (ö. 1067/1657). In: İslam Ansiklopedisi. Pp. 36–40 , accessed on July 4, 2015 (Turkish).

- ↑ Orhan Şaık Gökyay: Kātib Čelebi . In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition . tape IV . Brill, Leiden 1978, p. 760b-762a .

- ↑ a b Karin Rührdanz (1999): Oriental manuscripts in the Duchess Amalia Library. In: Goethe's Morgenlandfahrten. West-Eastern encounters (exhibition by the Goethe and Schiller Archives Weimar in the Goethe year, from May 26 to July 18, 1999), edited by Jochen Golz, Frankfurt am Main; Leipzig: Insel-Verlag, ISBN 3-458-34300-8 , pp. 97–111, pp. 98–101.

- ^ Entry to the Collection Persian Manuscripts and Rare Books , Leiden University Library

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Annemarie Schimmel : Oriental influences on German literature. In: Wolfhart Heinrichs (Ed.): Oriental Middle Ages. Aula-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1990, ISBN 3-89104-053-9 , pp. 546-562.

- ^ A b Paul de Lagarde: Persian Studies. 1884. (Reprint: Zeller, Osnabrück 1970), p. 5, footnote 8 and p. 9 with footnote 13. See section Saadis Bustan in the German language (1696) , possibly this print was already in 1644.

- ^ Digitized , Bavarian State Library digital

- ^ A b Maria Cäcilie Pohl: The importance of translation in the early baroque . In: Paul Fleming. I-representation, translations, travel poems , table of contents . Lit-Verlag, Münster 1993, ISBN 3-89473-579-1 , pp. 90-94; P. 209 footnote 51.

- ↑ a b c d e f Shafiq Shamel: The Convergence: European Enlightenment and Persian Poetry. In: Shafiq Shamel: Goethe and Hafiz. Poetry and ‹West-Eastern Divan›. Peter Lang, Oxford et al. 2013, ISBN 978-3-0343-0881-6 , Chapter 4, pp. 129–157.

- ↑ a b c d e Elio Brancaforte (2004, 2007 German): 1647: Adam Olearius publishes his experiences from Moscow and the Safavid Persia, which became the most popular travelogue of the Baroque. Dramaturgy of traveling , in: A New History of German Literature , edited by David E. Wellbery, Judith Ryan, Hans Ulrich Gumbrecht, Anton Kaes, Joseph Leo Koerner and Dorothea E. von Mücke. Translated by Christian Döring, Volker von Aue, John von Düffel, Peter von Düffel, Helmut Ettinger, Gerhard Falkner, Sabine Franke, Herbert Genzmer, Nora Matocza and Peter Torberg. Berlin University Press, Berlin, ISBN 978-3-940432-12-4 , pp. 383-388.

- ↑ Gvlistan: this is the Royal Rose Garden. which the most noble Poet, called Sadi among the Turks and Persians, made about three hundred and seventy years ago; there were all sorts of memorable previously unknown histories, also reasonable lessons and good teachings, so in times of peace and war also in the courage and common life to take care of. / First brought into French by Mr. Andrea du Ryer, Herren zu Malezair, & c ... and translated into the German language by Johan Friderich Ochssenbach anietzo. by Philibert Brunn, Tübingen 1636.

- ↑ Persianischer Rosenthal: in which many funny histories, astute speeches and useful rules 400 years ago by an ingenious poet Schich Saadi described in Persian / ietzo but by Adamo Oleario; with the addition of an old Persian name Hakwirdi, translated into High German, and adorned with many copper pieces. Holwein and Nauman, Schleszwig 1654. Digital copy of the Herzog August Library Wolfenbüttel

- ↑ a b c d Hamid Tafazoli (2007): Introduction and the sections With Paul Fleming to Persia , The Persian Poetry in the Mirror of German Baroque Literature and On the Reception of the 'Encyclopédie' in Germany . In: Hamid Tafazoli: The German Persia Discourse. On the scientification and literarization of the Persia image in German literature from the early modern period to the nineteenth century. Aisthesis, Bielefeld, ISBN 978-3-89528-600-1 , pp. 42–41, pp. 177–181 f. and pp. 284-307, pp. 314-321 and p. 584, respectively.

- ^ Claus Priesner: Olearius, Adam. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 19, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-428-00200-8 , pp. 517-519 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Harald Tausch (2012): “Memories of the earthly paradise. Persia and Alchemy with Paul Fleming and Adam Olearius “, in: Was ein Poëte kan! Studies on the work of Paul Fleming (1609–1640) . De Gruyter, Berlin, ISBN 978-3-11-027877-4 , pp. 369-408.

- ↑ 1655 performed at the court of Duke Christian von Wohlau; Christopher J. Wild (2004, 2007 German): Anatomy and Theology, Transience and Redemption , in: A New History of German Literature , edited by David E. Wellbery et al. Berlin University Press, Berlin, ISBN 978-3-940432-12-4 , pp. 389-393.

- ↑ Reinhard Kaiser (2014): “On the charm of detail. Grimmelshausen's beginnings as a narrator ”, epilogue in: Hans Jacob Christoffel von Grimmelshausen: Keuscher Joseph. Roman , from the German of the 17th century and with an afterword by Reinhard Kaiser. AB - The Other Library, Berlin 2014, ISBN 978-3-8477-3007-1 , p. 132.

- ^ Samuel von Butschky: Well-Bebauter Rosen-Thal: In it a curious mind / in all classes / all sorts of useful and amusing rarities and curious things; Time, world and statistic roses ... found in six hundred meaningful / uncommon speeches and reflections ... planted and incorporated; With a proper register. Hofmann, Nuremberg 1679.

- ↑ Table of contents of an edition from 1986 shortened by at least the third and fifth chapters (pdf)

- ↑ a b Wolfgang Struck (2009): "Looking for Persia in Persia and not finding it". Adam Olearius and Paul Fleming on the trip to Isfahan (1633–1639) . In: Writing in a foreign country. Contemporary literature on the trail of historical and fantastic voyages of discovery, edited by Christof Hamann and Alexander Honold. Wallstein, Göttingen, pp. 23-41.

- ↑ a b Heinz Entner (1989): Paul Fleming. A German poet in the Thirty Years' War , Reclam, Leipzig, ISBN 3-379-00486-3 , p. 447 and p. 451–452.

- ↑ a b c d e f Kambiz Djalali (2014): The foreign is one's own. The classical Persian poetry in the Franco-German area of the 19th century. Table of contents , Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg, ISBN 978-3-8260-5159-3 , p. 35, p. 59, p. 109, p. 245f., P. 248, p. 368.

- ↑ Barbara Becker-Cantarino: "Three letter autographs by Paul Fleming", in: Wolfenbütteler contributions: From the treasures of the Herzog August library , 1981; 4: 191-204.

- ↑ Michael Harbsmeier (1994): Wilde Völkerkunde. Other worlds in early modern German travelogues , Campus, Frankfurt am Main, p. 175.

- ^ Adam Olearius on Saadi and ingenious verses as a literary form (p. 618 of his travel description, expanded edition 1656), Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel / Wolfenbütteler Digitale Bibliothek

- ↑ Adam Olearius (1656), Chapter 27 "From their poets and their verses" , pp. 623–625, Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel / Wolfenbütteler Digitale Bibliothek

- ^ Johann Martin Lappenberg (1865): On the biography of Paul Fleming , section 3. The University of Leipzig , in: Paul Fleming's German poems , edited by JM Lappenberg, Litterarischer Verein, Stuttgart, pp. 658–659.

- ↑ See, for example, pages 00756 / 57,00799, 00805, 00807 of the digitized version of the extended edition from 1556.

- ↑ Hans-Georg Kemper: “‹ Think that in barbarism / Everything is not barbaric! ›On the Muskowite and Persian journey by Adam Olearius and Paul Fleming”, in: Description of the world. On the poetics of travel and country reports , edited by Xenja von Ertzdorff with the collaboration of Rudolf Schulz, Rodopi, Amsterdam 2000, ISBN 90-420-0480-0 , pp. 315-344, p. 343.

- ↑ List of participants

- ^ August Wilhelm Schlegel (1803/1804): Critical Writings and Letters , Volume 4: History of Romantic Literature , edited by Edgar Lohner. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1965, pp. 62-63.

- ↑ See section Prints in Persian before 1700 , Lagarde gives 1651 instead of 1644.

- ↑ Saadi Shirazi: Den Persiaanschen Bogaard, Beplant met zeer uitgeleesen Spruiten der Historien En Bezaait met Zeltzame Voorvallen, Leerzame en aardige Geschiedenissen, nephew Opmerkelijke Spreuken , translated into Dutch prose by Daniel Havart. Jan Claesz. ten Hoorn, Amsterdam 1688, reference in: Johanna Bundschuh-van Duikeren (2011): Dutch literature of the 17th century . De Gruyter, Berlin, ISBN 978-3-11-022381-1 , p. 520.

- ↑ Saadi Shirazi: The Persian Tree Garden: Planted with extravagant props of many stories, strange incidents, instructive histories and remarkable sayings , translated from Dutch by the editor of Adam Olearius: The world famous Adami Olearii colligated and much increased travel description . Zacharias Hertel, Thomas von Wiering, Hamburg 1696. Proof in part in: Johanna Bundschuh-van Duikeren (2011): Dutch literature of the 17th century . De Gruyter, Berlin, ISBN 978-3-11-022381-1 , p. 520.

- ^ Title page , Bayerische StaatsBibliothek digital / Munich Digitization Center Digital Library

- ^ Rudolf Gelpke (1959): Afterword , in: Nizami: The seven stories of the seven princesses , translated from Persian (in prose) and edited by Rudolf Gelpke, Manesse Verlag, Zurich, pp. 283–295, p. 292.

- ^ Fritz Meier (1941): Turandot in Persien , in: Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländische Gesellschaft , Volume 95, pp. 1–27, p. 5.

- ↑ Andrea Polaschegg (2005): From Beijing to Schiras: Schiller's 'Turandot' In: Der Andere Orientalismus. Rules of German-Oriental Imagination in the 19th Century . De Gruyter, Berlin 2005 (Reprint 2011) ISBN 978-3-11-089388-5 , pp. 205-219 and appendix.

- ↑ Jan Loop (2009): Review by Hamid Tafazoli, Der deutsche Persien- Diskurs , in: Arbitrium , Volume 27 (2009), 3, pp. 298-302, p. 300.

- ↑ Katharina Mommsen (1998): “Persien”, in: Goethe Handbuch , Volume 4/2, Personen, Dinge, Zeiten LZ, edited by Hans-Dietrich Dahnke and Regine Otto. Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar, pp. 841-843.

- ↑ Jennifer Willenberg (2008): Distribution and translation of English literature in Germany in the 18th century , Munich: Saur, ISBN 978-3-598-24905-1 , p. 320.

- ^ Text at Wikisource

- ^ Text at Wikisource

- ↑ Joseph von Hammer: The divan from Mohammed Schemsed-din Hafis . For the first time fully translated from Persian. Bookstore JG Cotta, Stuttgart and Tübingen 1812.

- ↑ Digitized: The divan by Mohammed Schemsed = Din Hafis. For the first time fully translated from Persian by Joseph v. Hammer. Cotta, Stuttgart and Tübingen 1812.

- ↑ a b c Johann Christoph Bürgel: Come, friends, the beauty market is! Comments on Rückert's Hafis transmissions. In: More Ali Newid (Ed.): Nightingales on God's Throne. Studies on Persian Poetry. Reichert, Wiesbaden 2013, ISBN 978-3-89500-948-8 , pp. 117-132.

- ↑ a b c d Jan Volker Röhnert (2007): "The divan in the Duchess Anna Amalia library", in: Hafis: The divan. From the Persian by Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall. Munich: Süddeutsche Zeitung (series Bibliotheca Anna Amalia), ISBN 3-86615-415-1 , pp. 989–995, pp. 989–999.

- ↑ Arthur Guy (1935): Introduction , in: Les Robaï d'Omer Kheyyam. Étude suivie d'une traduction française en décalque rythmique avec rimes àa la persane , Société Française d'Éditions Littéraires et Techniques, Paris, pp. 11–84, p. 15.

- ↑ a b Anil Bhatti (2007): "... floating between two worlds ..." On Goethe's experiment in foreignness in the West-Eastern Divan , in: Goethe. New Views - New Insights , edited by Hans-Jörg Knobloch and Helmut Koopmann. Königshausen and Neumann, Würzburg, pp. 103–122. (pdf at goethezeitportal.de)

- ^ Antonella Nicoletti (2002): Translation as an interpretation in Goethe's "West-Eastern Divan": in the context of early romantic translation theory and hermeneutics , Tübingen / Basel: Francke, ISBN 3-7720-2680-X , p. 312.

- ↑ Andrea Polaschegg: I am the Orient: Goethe's Poetology of the East. In: The Other Orientalism. Rules of German-Oriental Imagination in the 19th Century . De Gruyter, Berlin 2005 (Reprint 2011) ISBN 978-3-11-089388-5 , pp. 291-397.

- ↑ a b c Manfred Osten: Goethe's "West-Eastern Divan" and Heine's "Romantic School" , in: Harry .... Heinrich ... Henri ... Heine. German, Jew, European , edited by Dietmar Goltschnigg, Charlotte Grollegg-Edler and Peter Revers. Grazer Humboldt-Kolleg, 6. – 11. June 2006. Erich Schmidt Verlag, Berlin 2008, ISBN 978-3-503-09840-8 , pp. 267-270.

- ^ Translation by Friedrich Rückert : From the Ghazelas of Mewlana Dschelaleddin Rumi in the Gutenberg-DE project

- ↑ Reprint: Zeller, Osnabrück 1966. Sample page from the Persian edition .

- ↑ Grammar, Poetics and Rhetoric of the Persians / according to the 7th volume of the booklet Ḱolzum presented. by Friedrich Rückert. New ed. by W. Pertsch. Gotha: Perthes, 1874 (scan can be read online), menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de

- ↑ Peter-Arnold Mumm (2013): Friedrich Rückert's Bostan notes and their linguistic background , in: Saadi's Bostan . Translated from Persian by Friedrich Rückert, Volume 8 of the Schweinfurt edition: Works from the years 1850-1851, Volume 2 Edited by Jörn Steinberg, Jalal Rostami Gooran, Annemarie Schimmel and Peter-Arnold-Mumm. Wallstein, Göttingen 2013, ISBN 978-3-8353-0495-6 , pp. 445–459, p. 445.

- ↑ Transcription according to DMG .

- ↑ s. also under Rückert and Hafis

- ^ Friedrich Rückert: Poetisches Tagebuch, 1850–1866 (from his estate) , first edition by JD Sauerländers Verlag, Frankfurt / M 1888.

- ^ " Translations of Hafez in German ", Encyclopædia Iranica

- ↑ Jochen Golz: Foreword . In: Goethe's Morgenlandfahrten. West-east encounters. (Exhibition by the Goethe and Schiller Archive Weimar during the Goethe year, from May 26 to July 18, 1999), edited by Jochen Golz, Frankfurt am Main; Insel-Verlag, Leipzig 1999, ISBN 3-458-34300-8 , pp. 9–15, p. 11.

- ↑ a b Diethelm Balke (2001): "Orient and oriental literatures (influence on Europe and Germany)", section "§ 52. The German literature borrows materials and motifs from Arabic pers. Poetry for light and meaningless arrangements from ", in: Reallexikon der deutschen Literaturgeschichte , Volume 2, LO, pp. 816–869 (" excludes biblical, Christian, Jewish and ancient oriental suggestions. "), P. 845.

- ^ According to statistics in Ammann, Ludwig (1989): Ostliche Spiegel. Views of the Orient in the age of its discovery by the German reader, 1800–1850 , Hildesheim: Olms, p. 17; referenced in: Georges Tamer (2014): "Conceptual thinking about the Orient: Reflections on research into the Arabic-Islamic intellectual history", in: Asiatische Studien - Études Asiatiques , Volume 68, Issue 2, pp. 557–577, p. 559, footnote 9.

- ↑ a b Navid Kermani (2015): Between Koran and Kafka. West-eastern explorations , 2nd, reviewed edition (first in 2014), Beck, Munich, ISBN 978-3-406-66662-9 , pp. 64–65.

- ↑ a b Andrea Polaschegg (2005): Brief History of Orientalism Research , Section 1.1 in: The Other Orientalism. Rules of German-Oriental Imagination in the 19th Century . De Gruyter, Berlin 2005 (Reprint 2011) ISBN 978-3-11-089388-5 , pp. 10-27.

- ↑ a b c Gerrit Wustmann (2011): Foreword , in: Here is Iran! Persian poetry in German-speaking countries , edited by Gerrit Wustmann. Sujet Verlag, Bremen, ISBN 978-3-933995-75-9 , pp. 11-23.

- ↑ Kurt Scharf (2005): On the history of Persian poetry , in: The wind will kidnap us. Modern Persian poetry , selected, translated and introduced by Kurt Scharf. Beck, Munich, ISBN 3-406-52813-9 , pp. 17-23, p. 23.

- ↑ See Persian Reader. Fārsī, Darī, Toǰikī. Original texts from ten centuries with commentary and glossary , edited by Mehr Ali Newid and Peter-Arnold Mumm. Reichert, Wiesbaden 2007. ISBN 978-3-89500-575-6

Web links

- Simon Kremer in an interview with editor Gerrit Wustmann: “Iranian poetry is more direct than German” . ( Memento of March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Souk Magazine, June 5, 2012