Alain-René Lesage

Alain-René Lesage or Alain René Le Sage (born May 8, 1668 in Sarzeau , Bretagne , † November 17, 1747 in Boulogne-sur-Mer ) was a French writer with a socially critical eye and a sense of humor. He is considered the first author of French literature who lived entirely from selling his products on the literary market, which began to develop around 1700. He made use of a number of models, such as Spanish Picaresque literature. He probably had no educational or even revolutionary intentions. His first novel The Limping Devil is the first European metropolitan novel , Lesage became better known for his main work The Story of Gil Blas von Santillana .

life and work

As the son of a notary, Lesage came from a middle-class legal family, but lost both parents in his childhood and later also lost his inheritance, which his uncle embezzled as guardian. After completing his schooling with the Jesuits in Vannes ( Morbihan department , Brittany ), he studied law in Paris , was admitted to the bar and received a post in tax leases in Brittany, i. H. the then privately organized system of tax collection. After he soon lost this post for unknown reasons and was unable to establish himself as a lawyer, he went to Paris in 1698 to work as an author, initially of translations such as the letters of Callisthenes .

After getting to know the Spanish language and literature with the Abbé of Lyonne, who supported him with a pension of 600 francs, his career began with little successful transcriptions and adaptations of Spanish plays. His breakthrough came in 1707 with the self-written comedy Crispin, rival de son maître (Crispin as his master's rival).

The first version of the novel Le Diable boiteux (The Limping Devil), based on a Spanish model by Luis Vélez de Guevara and published in the same year (the final version was completed in 1726), also had a very good impact. In it the author looks at the city of Madrid (representing Paris) with the help of a devil freed from a bottle.

In 1709, Lesage achieved a scandalous success with the comedy Turcaret , which, in the character of the title hero, pilloried the Parisian bankers and tax farmers, the “financiers”, interspersed with lying upstarts. The piece, which comes up with “masterful realistic representational skills and sharpness”, which was fought against by those who felt affected during the rehearsal at the Comédie-Française , was only performed thanks to a powerful word from the Dauphin . Before Lesage, no one had dared “to express the protest of the exploited so effectively”.

After his bad experiences with the turcaret and the Comédie-Française, Lesage turned to the popular Parisian Théâtre de la Foire . For this he wrote over the next few decades, some with co-authors, probably more than 100 funny, if less aggressive pieces that served the Kurzweil and Lesages household budget. He also wrote some novels that are now forgotten.

History of Gil Blas

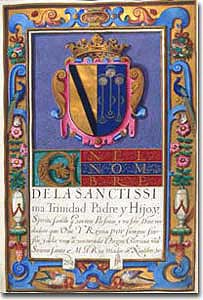

Around 1715 he began the book that is considered to be his main work and the best French Picaro novel. It is the storytelling, still legible Histoire de Gil Blas de Santillane (History of Gil Blas of Santillana), published in four volumes between 1715 and 1735. The story, which has been relocated to Spain, actually reflects contemporary French conditions, although from the perspective of the simple-minded and witty first-person narrator and protagonist, son of a stable master and a chambermaid, the most diverse milieus from the bottom to the top are presented in a satirical and critical way. Lesage covered the contemporary French reality with so much Spanish local color from the time of Philip III. that Voltaire accused it of an adaptation of the older Spanish picaresque novel La vida del escudero don Marcos de Obregón by Vicente Gómez Martínez-Espinel , apparently because he believed himself to be caricatured in the minor character of the literary figure Don Gabriel Triaquero. The allegation of the Palgiat was refuted by CF Franceson in 1857: Only about 20 percent of the novel, especially the minor characters, are borrowings from older Spanish models. The subsequent fourth part of the novel is not as dense and full of tension as the preceding parts, but shows the basically unlimited expandability of the picaresque type based on loosely connected episodes, which in this case covers the period from the hero's youth to around 70. Year of life. However, numerous characters appear again and again in the course of history.

Characteristic of the period of the decline of Spain under Philip III. and Philip IV is the constant competition of courtiers for closeness to the greats of the empire such as the Duke of Lerma or the Duke of Ucedo, whose favor can quickly be lost through intrigue. Gil Blas, however, initially eagerly participates in this game of intrigue, characterized by chance and arbitrariness, which leads to the breathtaking rise and fall of even great men. The economy of honor, ministerial absolutism and the permanent struggle of the parasitic court nobility for closeness to the grandees and for the granting of benefices, benefits and favors are features of this epoch, as well as the corruption-poisoned administration and the terror of the police apparatus.

Special attention is paid to the medical booth with its bloodletting and urination methods . The guild of actors is also portrayed as depraved and unrestrained; they were something like today's pop stars and popular at court.

At the same time, and this is new for the genre, Lesages Picaro is initially a naive but relatively educated person, who in the course of the episodic narrative also experiences a maturation in character, which anticipates features of the later genre of Bildungsroman .

Tobias Smollett translated the novel into English. This translation influenced the English novel of the late 18th century.

The figure of Gil Blas was known to all educated French as a prototype of the sharp-eyed and at the same time thick-skinned scoffers into the early 20th century, not least as the namesake of the satirical magazine that existed from 1879 to 1914 , in which z. B. Guy de Maupassant and Jules Renard published.

Arthur Schopenhauer recommended in his treatise "on education" Gil Blas as one of the very few novels that convey realistically "how things actually go in the world".

For French-speaking readers, the novel is recommended as a practice reading because it contains many verb forms that are no longer in use today.

Private life

Little is known about Lesage's personal life. In 1694 he married Marie Elizabeth Huyard, daughter of a carpenter. The marriage had three sons and one daughter.

He disinherited his eldest after he could not be dissuaded from becoming an actor. However, when the disobedient had made it into high society, Lesage was reconciled with him and hardly left his side.

Lesage wrote tirelessly and did not retire until he was 70. At the age of 80, he and his ear trumpet were still a welcome guest and popular conversation partner in Parisian cafés.

Aftermath

In Vannes, the Lycée Alain René Lesage today commemorates the educated mocker. A street in Grenoble is named after him.

Editions of works and translations

A 16-volume complete edition of Lesage's works was published in 1828.

- The limping devil. Novel. From the French by G. Fink. New ed. and introduced by Otto Flake . With illustrations by Fritz Fischer . Mosaic, Hamburg 1966.

- Lesage: The Limping Devil. (= Insel Taschenbuch. Volume 337). Editing of the translation (from the middle of the 19th century) by G. Fink by Meinhard Hasenbein. With illustrations by Tony Johannot (from the French edition published at the same time as Fink's translation) and an afterword by Karl Riha . Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1978, ISBN 3-458-32037-7 .

-

The story of Gil Blas of Santillana. Translated by Konrad Thorer. Insel Verlag, Leipzig 1941, 1958.

- New edition: Insel, Frankfurt 1997. With illustrations by Daniel Chodowiecki . ISBN 978-3-458-32649-6 .

literature

- Vincent Barberet: Lesage et le théâtre de la foire . Nancy 1887.

- Leo Claretie: Lesage romancier . Paris 1890.

- Eugene Lintilhac: Lesage . Paris 1893.

- Marcello Spaziani: Il teatro minore di Lesage . Rome 1957.

- Felix Brun: Structural changes in the picaresque novel. Lesage and its Spanish predecessors . Zurich 1962.

- Uwe Holtz: The Limping Devil by Vélez de Guevara and Lesage. A literary and socially critical study . Wuppertal 1970.

- Roger Laufer: Lesage ou le métier de romancier . Paris 1971.

- Winfried Wehle : Coincidence and Epic Integration. Change of the narrative model and socialization of the rogue in the "Histoire de Gil Blas de Santillane". In: Romance Yearbook. Volume 23, 1972, pp. 103-129. ( ku-eichstaett.de (PDF; 1.4 MB) accessed in August 2011)

- Karl Riha: Afterword. In: Lesage: The Limping Devil. (= Insel Taschenbuch. Volume 337). Editing of the translation by G. Fink by Meinhard Hasenbein. With illustrations by Tony Johannot . Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1978, ISBN 3-458-32037-7 , pp. 365-378.

- R. Daigneault: Lesage . Montreal 1981.

- Francis Assaf: Lesage et le picaresque . Paris 1983.

- Cécile Cavillac: L'Espagne in the trilogy "picaresque" de Lesage . Bordeaux 1984.

- Jacques Wagner: Lesage, écrivain . Amsterdam 1997.

- Robert Fajen: The Illusion of Clarity. Style reflection and anthropological discourse in Alain-René Le Sage's “Gil Blas”. In: Archives for the Study of Modern Languages and Literatures . Volume 289, 2002, pp. 332-354.

- Christelle Bahier-Porte: La Poétique d'Alain-René Lesage . Champion, 2006.

Web links

- Literature by and about Alain-René Lesage in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Alain-René Lesage in the German Digital Library

- Works by Alain-René Lesage at Zeno.org .

- Works by Alain-René Lesage in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Gil-Blas from Santillana in the translation by Ernst Wallroth. Stuttgart 1839

- Publications by and about Alain-René Lesage in VD 17 . (No entries on February 11, 2018)

- Via Lesage on the Internet Archive

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gert Pinkernell , Frz. History of literature , accessed March 30, 2013.

- ↑ Winfried Engler : Lexicon of French Literature (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 388). 2nd, improved and enlarged edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-520-38802-2 .

- ↑ Lesage: The Limping Devil. Editing of the translation by G. Fink by Meinhard Hasenbein. (= Insel Taschenbuch. Volume 337). With illustrations by Tony Johannot and an afterword by Karl Riha. Insel, Frankfurt am Main 1978, ISBN 3-458-32037-7 , p. 2 (publisher's foreword).

- ↑ a b Kindler's New Literature Lexicon , Munich 1988 edition, online via the Munzinger archive via public libraries

- ↑ According to the Brockhaus Enzyklopädie (19th edition. Volume 8 from 1989, p. 522) , the first edition with 600 woodcut vignettes by Jean-François Gigoux is also considered a major work of romantic book illustration

- ↑ Eugène E. Rovillain: L'Ingénu de Voltaire; Quelques Influences. In: Modern Language Association: PMLA 44 (1929) 2, p. 537.

- ↑ (HHH :) Histoire de Gil Blas de Santillane. In: Kindlers new literature lexicon, ed. by Walter Jens, Munich 1996, volume 10, p. 273 ff.

- ↑ (HHH :) Histoire de Gil Blas de Santillane. In: Kindlers new literature lexicon, ed. by Walter Jens, Munich 1996, volume 10, p. 274.

- ↑ Wolfgang U. Eckart : Medical criticism in some novels of the baroque period - Albertinus, Grimmelshausen, Lesage, Ettner. In: Wolfgang U. Eckart and Johanna Geyer-Kordesch (ed.): The health professions and sick people in the 17th and 18th centuries. Source and research situation. (= Munster contributions to the history and theory of medicine. No. 18). Burgverlag Tecklenburg 1982, ISBN 3-922506-03-8 , on Alain-René Lesage pp. 59–62.

- ↑ Friedrich v. Zglinicki : Uroscopy in the fine arts. An art and medical historical study of the urine examination. Ernst Giebeler, Darmstadt 1982, ISBN 3-921956-24-2 , p. 149.

- ^ The Adventures of Gil Blas of Santillane. A New Translation. Joseph Wenman, London 1780.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lesage, Alain-René |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | French author |

| DATE OF BIRTH | May 8, 1668 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Sarzeau , Brittany |

| DATE OF DEATH | November 17, 1747 |

| Place of death | Boulogne-sur-Mer |