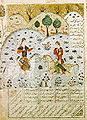

Chosrau and Shirin

Chosrau and Schirin is a love story edited by many poets (such as Firdausi ), which found its completion in the well-known epic by the Persian poet Nezami from around 1200 .

The classic triangular story describes the love of the (also historically existing) Persian Great King Chosrau II and the sculptor Farhad (Farhād) for the Shirin, who comes from Armenia as the daughter of the regent there . Although Chosrau and Shirin fell in love as a young princess and prince, after the court painter Schapur had reported about Shirin and advertised for them in Armenia with a portrait of Khosrau, it was long years before they married. Chosrau, especially fond of pleasure and wine, has to go through a process of maturation and many other relationships before he is worthy of his shiress, who was promised to him in a childhood dream. Shirin, on the other hand, who fled the maternal palace to the Persian court in Ctesiphon to get to Chosrau , is portrayed from the beginning as a virtue in person and is clearly the stronger part. In the course of the story, Shirin and Chosrau miss each other again and again and one first personal encounter only takes place in Armenia after Chosrau had ascended the throne in Ctesiphon.

Well known is the chapter in which the sculptor and builder Farhad falls unhappily and immortally in love with Schirin after he had sent a milk pipe from Schapur to the desert castle where Schirin lived. Chosrau then gives him the task of cutting a pass road into the Bisotun mountain with an ax . Inspired by his love, Farhad survives this work and shows himself to be the more worthy lover. Chosrau Farhad sends the wrong message that Shirin has died, and the gullible, desperate Farhad throws himself into the ravine, where he is found dead by Shirin. Schirin had a dome built over his grave to serve as a memorial for faithful lovers. The figure of Farhad became the central figure in many imitations of the epic and literally for superhuman achievement. Even Soviet propaganda used the "worker" Farhad.

The love between Chosrau and Schirin, however, continues. Chosrau sends the famous musician Barbad to her to woo Shirin after the death of his first wife . At the end of the story, Shirin kills himself after Chosrau has been murdered in a dungeon initiated by his son.

Nezāmi's epic can also be read on a metaphorical level. On this, Schirin is the symbol for love itself, and Chosrou must have erotic (his first wife, the Byzantine princess Maryam) and aesthetics (his second wife Schakkar, "sugar") as precursors to true love (Schirin, "sweet") detect. On a stylistic level, the sunrises and sunsets are particularly famous, the way in which the poet portrays them gives a premonition of what will happen next.

The epic served as a model for numerous Persian, Turkish and Indian poets. Some key scenes, such as the scene in which Shirin falls in love with a picture of Chosrau, and the one in which Chosrau meets the naked Shirin at a spring and the two run away from shame without having recognized each other, are popular motifs of the Persian Miniature painting . Around 1860 Johann Gottfried Wetzstein recorded the Arabic shadow play The Lovers of Amasia in Damascus , in which the story of Farhad (Farhād) and Schirin is combined with the main characters of the Turkish Karagöz theater .

Under the Turkish name Hüsrev ü Şirin, the epic forms the narrative frame of the novel Rot ist mein Name (1998) by the Turkish Nobel Prize winner Orhan Pamuk , who took the form of a historical Islamic picture dispute in the late 16th century as a result of the use of perspective painting in European art Detective novels u. a. processed with the inclusion of fantastic elements .

expenditure

- Chosrou and Schirin. Trans. V. Johann Christoph Bürgel. Manesse, Zurich 1980, ISBN 371751590X .

See also

- Wīs and Rāmīn (11th century) from Fakhr-od-Dīn Ās'ād Gorgānī

- Persian literature

literature

- Stuart Cary Welch: Persian illumination from five royal manuscripts of the sixteenth century. Prestel-Verlag, Munich 1976, 2nd edition 1978 ( ISBN 3-7913-0388-0 ), p. 57 (Diwan des Nawa'i ) and 80-87 (Chamsa des Nizami).

- Peter Lamborn Wilson , Karl Schlamminger: Weaver of Tales. Persian Picture Rugs / Persian tapestries. Linked myths. Callwey, Munich 1980, ISBN 3-7667-0532-6 , pp. 46–77 ( Die Liebesdichtung ), here: pp. 46–49 and 58–67.