Arabic shadow play

The Arabic shadow play ( Arabic خيال الظل chayāl az-zill , DMG ḫayāl aẓ-ẓill al-ʿarabī 'Fantasy of Shadows') belongs to the Asian tradition of shadow play and is mentioned for the first time in a written source in the 11th century. It is to be distinguished from the Arab theater ( chayāl ) with costumed human character actors ( chayālī ),which has been known since early Islamic times.

In the three surviving pieces by the Cairo- based poet Muhammad ibn Dāniyāl (1248–1311), a distinct form of shadow play in Egypt can be recognized. The texts are written as poems and rhyming prose ( maqāma ). The main character in the first play wants to start a middle-class family after a vicious life that has been described in great detail. In the second piece, jugglers, trick thieves and other dodgy characters appear one after the other, and the third piece is about a homosexual love affair with all sorts of excesses, which, after the protagonist's repentance, comes to a moral end with a "just punishment". The shadow plays with figures made of dried animal skin dealt with everyday life in Cairo and enjoyed great popularity among all strata of the Egyptian people until their gradual disappearance after the 16th century. They probably influenced the Turkish Karagöz theater , the oldest piece of which has been handed down from the 16th century.

In the 19th century European explorers reported of undemanding, often obscene performances in the cities of the Maghreb , the content and characters of which were flattened adoptions of the Turkish shadow theater that had become famous in the areas of the Ottoman Empire . Its main character has been called Karagöz since the 17th century. In the Maghreb this popular entertainment was banned by the French colonial authorities in 1843, but it was maintained in its coarse language until the beginning of the 20th century.

In the second half of the 19th century, the Egyptian shadow play was revived by Hasan el-Kaschasch, who took up pieces from the time of Ibn Dāniyāl and presented them in a modified form. By the middle of the 20th century, this renewed Egyptian shadow play was practically non-existent.

origin

Everyone agrees that shadow play was invented in Asia; however, where and when is not certain. “I am only my shadow, soon only my name” ( Friedrich Schiller : Wilhelm Tell ). The twofold “only” refers in the common notion to the subordination and the merely derived existence of the shadow of a person or an object. For the viewer who is deeply immersed in the shadow play, on the other hand, the shadow appears as the actual actor in a world of its own and the shadow-casting figure as only secondary. This idea and its playful implementation may have come up at different times in several places. The tradition has always been passed down orally and can therefore only be traced back to a limited extent in literature.

The oldest literary sources in which puppet and shadow theater are mentioned include the Indian epic Mahabharata (recorded in writing from the 4th century BC) and that around 80 BC. Written Buddhist work Therigatha . The shadow play, which is still cultivated in several variations in South India today, possibly came from India in the first centuries after Christianity to Southeast Asia, where the wayang kulit is particularly well known in Indonesia. According to another opinion, the wayang kulit is an independent Indonesian invention.

The Chinese shadow play has a different shape and history , which can only be historically proven from the 11th century, but anecdotally referred to as its origin to an event in the Han dynasty (206 BC - 220 AD) . A Taoist magician would have made the soul of a deceased wife of Emperor Wu (156-87 BC) appear again with the help of lamps on a curtain. At least that's what the Han Shu dynasty history says . Playing with reality and an otherworldly world is a thematic link between East Asia and India, which was part of the lecture of bailiff singers who presented scrolls. According to the orientalist Georg Jacob (1930), singers wandering around with picture scrolls on which pictures of Hell could be seen represent a possible preliminary stage for the Chinese shadow play. There were those, yamapata (from Yama , god of death, and Sanskrit pata , " Canvas "," Curtain ") called picture scrolls in India since the early Middle Ages. In West Bengal they are part of the Patua storytelling program . Their equivalent in Japan, which Buddhist beggars showed up until the beginning of the 20th century, was called yemma yezu ( yemma, emma, corresponding to yama, yezu, "image"). In Indonesia, scrolls used to illustrate stories are known as wayang beber .

The anecdote from the Han dynasty about the origin of shadow play in China is still present because it was repeated several times by a Chinese historian in the 11th century and later. Georg Jacob makes a connection with a similar story from the Middle East. One night in Kufa a Jew named Batruni performed a magic piece of magic. In the “shadow play” a famous Arab king appeared on his horse riding through the mosque courtyard. The performance ended tragically for Batruni, he was accused of witchcraft and executed.

In favor of the basically accepted eastern origin of the Arabic shadow play, which can be proven in Egypt from the 11th century, very different routes of propagation are considered possible. According to Bill Baird (1973), Turkic peoples traveled through Central Asia before the 11th century with a puppet theater they called kogurcak ( kolkurcak, meaning "puppet figures that appear behind a curtain"). Following the example of the Scythians , who had cut figures out of animal skin in pre-Christian times, cattle nomads could have projected shadow figures onto tent walls with the light of a fireplace. Figures cut out of animal skin, paper, fabric or bark had a magical meaning among the Manchu in northeastern China and were part of shamanic rituals. In the historical region of Turkestan , the shadow play is said to have been known as çadır hayal ( çadır, Turkish “tent”, hayal , “fantasy”, meaning “presentation in a tent”). But maybe then as now, çadır hayal meant puppets . In any case, Turkestan is considered to be the region of origin of hand puppets (Turkish kol korçak ) and marionettes (cf. the Afghan goat puppet buz bazi ). The path of the shadow play from Central Asia directly to Anatolia seems unlikely, because nothing has been handed down from the Turkish Karagöz before the 16th century. This was preceded by puppet shows in Anatolia. Nevertheless, some Turkish researchers lead the Karagöz undeterred to Central Asia and back to the Hittites .

In addition to the long land route through Central Asia, it was proposed to spread the shadow play along the shipping routes from the South China coast through the islands of Southeast Asia to Egypt, i.e. on similar routes that the Dutch East India Company later sailed. The argument put forward is that at least the delicate Chinese celadon porcelain reached Egypt by sea in the 11th century.

Metin And (1987) considers it probable, due to the similarities of the characters and the course of the performance between Karagöz and wayang kulit , that Arab traders first brought the shadow play from Java to Egypt, from where it later came to Anatolia. Arab coin finds on the west coast of Malaysia have been evidence of Arab maritime trade via Southeast Asia with China since the 9th century. In the centuries that followed, Arab emigrants settled on Indonesian islands and shaped the local culture. A striking match is the Javanese figure of the tree of life and world mountain gunungan ("mountain", "mountain-like"), which belongs to the ceremonial opening of a Javanese piece and corresponds in its function to the Turkish figure göstermelik . Only when certain music has played does the shadow player remove the göstermelik with his hand and the performance begins.

Finally, numerous similarities in the design of the figures speak for a direct connection between the Indian shadow plays and the Egyptian. Here, as there, there are large, richly ornamented figures that are mostly rigid, although there are considerable shadow play traditions that are still cultivated in southern India (including Tholpavakuthu in Kerala , Tholu bommalata in Andhra Pradesh , Togalu gombeyaata in Karnataka and Chamadyache bahulya in Maharashtra ) Differences there.

Research history

The Arabic sources provide information about the earlier performance practice of the Arabic shadow play in Egypt. The North African variant of Karaguz has only been known since the 19th century through reports from French and German travelers. Hermann von Pückler-Muskau shares Semilassos penultimate world course. In Africa (1836) his disgust with the obscenity of a shadow play performance in Algiers . Moritz Wagner also reports on the shadow play in Algiers in Journeys to the Regency of Algiers in 1836, 1837 and 1838 (1841). Accordingly, the characters fought on the shadow theater from start to finish and made rough jokes. The language was a mixture of Arabic and French, the latter to entertain the Europeans present. Wagner too expresses his disgust at the profanity against which the French colonial administration would do nothing. The French writer Ernest Feydeau ( Alger, Paris 1862, pp. 128–130) stayed in 1844 in Algiers. The traveler and writer Heinrich von Maltzan spent his three years in the north-west of Africa (travels in Algeria and Morocco, Leipzig 1863) during Ramadan in Algiers, where he watched the nightly entertainment program, which was more moderate than in Constantinople . Here he experienced the shadow play as "the only noisy Ramadan pleasure". In Constantine , he visited a "booth in a dark alley where this buffoon from the Bosphorus was doing his being". After all, he found a few hundred visitors there, a “raw public” that was made laughing by the jokes.

In 1853 Richard Francis Burton experienced a shadow play on his pilgrimage to Mecca in the great Esbekiye Square in Cairo ( Personal narrative of a pilgrimage to El Medinah and Meccah, London 1855). Another European visitor to a shadow play in Cairo was Crown Prince Rudolf of Austria-Hungary . In his honor, among other things, “Turkish shadow plays” were performed in the Esbekiye Garden, as mentioned in Eine Orientreise from 1881 (Vienna 1885). Georg Jacob (1906) gives an overview of the general literature on shadow play up to 1900 .

In the middle of the 19th century, the Munich orientalist Marcus Joseph Müller (1809–1874) made a partial copy of a manuscript of Ibn Dāniyāl's pieces. The first monographic description of the North African shadow play comes from Max Quedenfeldt (1890). Georg Jacob deals with the origin of the North African shadow play from the Karagöz for the first time in The Turkish Shadow Theater (Berlin 1900). In this he sees only slight relationships between the Turkish and the Maghrebian shadow play, with regard to the influence from one to the other, he tends in the wrong direction. His pioneering work The History of Shadow Theater in the Orient and Occident from 1907 appeared in a second, significantly expanded edition in 1925. It contains on pages 227–284 a summary of the Arabic shadow play and the first detailed description of the three pieces by Ibn Dāniyāl. At Jacob's request, the orientalist Paul Kahle took on the task of continuing his work. Kahle researched a fragmentary piece that he considered to be the oldest known shadow play from medieval Egypt and compared it with contemporary performances ( The Lighthouse of Alexandria, 1930, previously The Crocodile Game, 1915). Otto Spies wrote an article in 1928 about shadow theater in Tunisia. The Israeli orientalist Jacob M. Landau wrote Shadow plays in the Near East in 1948 as the successor to Georg Jacob. Other authors focus on the Turkish shadow play, for example Metin And ( A History of Theater and Popular Entertainment in Turkey, Ankara 1964).

The Egyptian Ibrahim Hamada published an Arabic text edition of Ibn Dāniyāl's three pieces in Cairo in 1963, but it is based on only one of the four existing manuscripts and has been so heavily revised that about half of the text is missing. Nevertheless, it formed the basis of several subsequent studies.

Medieval Egyptian shadow play

God as the supreme puppeteer, the eternal first mover ( muharrik ), who directs people's fate, is a metaphor that occurs frequently in the poetry of the late medieval Sufi poets. In the puppet show they saw "... the symbol of God's actions in the world." The expression chayāl az-zill , ("dream / fantasy of the shadows") appears for the first time in a philosophical verse by the legal scholar asch-Schāfiʿī (767-820) . In it he observes how human beings and spirits come and go, which he recognizes as transitory and only their ruler as permanent. The existential truth expressed here is also to be found in a verse by the poet Abu Nuwas (757-815), in which chayāl az-zill is described as a light form of entertainment, which includes wine and music. The scholar Ibn Hazm (994-1064) gave a technical description of what was perhaps understood by chayāl az-zill at that time: a kind of magic lantern in which figures mounted on a wooden wheel turned in a circle at high speed. At the same time, Ibn Hazm's philosophical analogy of passing and disappearing figures with successive generations of people, which ultimately goes back to Aristotle 's God as the "immobile mover", formed the starting point for the symbolism of the Sufis.

Az-zill, "shadow" versus an-nūr , "light", is a pair of opposites that often occurs in Islamic metaphysics : the derived versus primary existence. The local world ( ad-dunyā ) is the shadow of the absolute for Ibn ¡ Arab∆.

Cultural environment

During the Caliphate of the Fatimids , who ruled the newly founded capital Cairo from the 10th to the 12th centuries, the Shiite rulers attached particular importance to shining their faith with their Sunni predecessors through lively construction and the development of cultural activities spread. This included the introduction of festive events for the entire population, especially the festival for the birthday of the Prophet, Maulid an-Nabī . The innovations also included the generous use of figurative images according to the Shiite tradition, which is expressed in depictions of humans and animals framed by landscape or architectural details in book illumination and in handicraft production. For the Maulid festival, to the delight of the girls, dolls made of icing were introduced, which are surrounded by an umbrella-like structure made of folded, colored paper. Boys got a horse made from sugar paste. Both figures refer in their symbolism to pre-Islamic times.

The visitors to the large markets in the late medieval Islamic cities were the audience for acrobats, dancers and musicians. There were storytellers ( qās ), Muslim preachers ( chatīb ), heralds of the biography of the prophets ( as-Sīra an-Nabawīya ), storytellers ( hakawati ) and improvising singers ( munshid ) at the religious meeting places and in the coffee houses . The singers maintained the epic storytelling tradition ( sīra ) and accompanied each other on the one-stringed fiddle rabāba . Another poetic style of singing is the mawwāl (plural mawāwīl ), which was accompanied by rabāba and wind instruments. The mawwāl often contained jokes directed against the authorities. The hākī ( hākiya ) was a storyteller or pantomime character actor who slipped into various roles. His stories ( hikāya ), which belong to the area of popular culture , may have influenced the courtly poetic genre maqāma and his performances could have been a model for shadow play ( chayāl az-zill ). According to Shmuel Moreh (1992), the names chayāl, maqāma, risāla (“message” to God), hikāya, muhāwara (“dialogue”, “conversation”), munāzara have been used for both narrative and dramatic genres since the 11th century ("Debate") and hadīth ("narration"). Narrative lecture and a type of staging belonged inseparably together in all cases.

Under the strict Mamluk Sultan Baibars I, a climate of oppression prevailed in Egypt. Unpleasant pleasures and the consumption of alcohol were strictly forbidden. This only changed with the death of Baibar in 1277, when a kind of general carnival mood arose. The court seemed to want to distract itself from the constant internal power struggles and the wars against the Mongols through parties and public festivals with comedies and masquerades. Ibn Dāniyāl takes over the exuberant atmosphere in his pieces.

The shadow play remained unaffected by prohibitions even with a strictly religious authority and thus differed from other depicting arts. According to a certain Islamic tradition of the prohibition of images , no pictorial representations of people should be made in order not to compete with God as the only Creator. According to this point of view, lifelike dolls may not be shown directly, but their shadows may. In the Ottoman period, holes were cut in the figures so that the spirits could escape from them, which also made the shadow play an art form acceptable to the Islamic clergy.

Word meaning

In the pre-Islamic and early Islamic times, chayāl was understood to mean "figure" or "statue". In a Naqā'id (poem form of the counter-speech) between Jarīr and al-Farasdaq (late 7th / beginning 8th century), the Arabic word chayāl once denotes a scarecrow ( kurradsch ) to keep wolves away from the flock of sheep, and another time a hobby horse . In a somewhat more comprehensive sense than a “hobby horse”, chayāl becomes a “play” in which fights are represented and musically accompanied by wind instruments and frame drums ( daf ). In this word meaning as “drama” and “imitation”, chayāl occurs in the 9th century and is synonymous with the verbal noun hikāya , which originally meant “imitation”, which later became “narrative”, “story”.

Since the 8th century, chayāl has meant in the general sense a fantasy of the beloved who appears in a dream at night, or the idea of a ghost, a shadow and the illusion of a human figure. In the Lisān al-ʿArab of the scholar Ibn Manzūr (1233-1311) chayāl occurs with the vague description as a phantom figure. With the meaning of “imagination”, chayāl found its way into the Urdu and Hindi languages . In India, a classical music style is called khyal and a theatrical style is also called khyal . The addition az-zill ("the shadow") came up with the introduction of shadow theater in the 11th century to distinguish it from the performances with human actors, which are still called chayāl . Both actors and the presenters of the shadow play figures were now called chayālī or muhāyil , with actors also being delimited as arbāb al-chayāl . The change in meaning of chayāl led from "figure", "fantasy" and "shadow" to "drama".

Origin and Distribution

The already mentioned Batruni from Kufa led in 7./8. Century with his chayāl perhaps continued an acting tradition from pre-Islamic times. Only a few plays are known from the Arab Middle Ages, for example from the time of the Abbasid caliph al-Mahdi (r. 775–785). Ibn Shuhaid (992–1035), Ibn Quzmaz (1078–1160) and Ibn al-Hajj (1250 / 56–1336) mention, among others, plays. Abd al-Baqi al-Ischaqi († 1660) wrote the only completely preserved text for an Arabic play.

An assumed literary reference to a shadow play in Egypt in the 9th century is not very informative. The first reliable mention of the shadow play - albeit without the name chayāl az-zill - comes from the mathematician and astronomer Alhazen (around 965-1039 / 40), who speaks of translucent figures in his scientific work Kitāb al-Manāzir , who are a demonstrator moved in front of a canvas so that the shadows of these figures can be seen on the canvas and on the wall behind it. Alhazen lived in Egypt around the same time as the Andalusian Ibn Hazm (994-1064), for the chayāl az-zill (in his work Kitāb al-Achlāq wa 'I-Siyar ) the already mentioned, rotating lanterna magica was. Under the title Chayāl Ja'far ar-Rāqis ("The Dancer Jafar's Game"), al-Hafaji mentions a possibly third type of shadow play in Shifa 'al-Ghalil , in which an actor moved along a curtain onto which the light fell a lamp cast its shadow. In the 11th century there seems to have been a shadow play with figures in Egypt, which is often mentioned in the 12th and 13th centuries under the name chayāl az-zill . Emphasizes an anecdote about Saladin (1137-1193), who convinced his rather hesitant Grand Vizier Qādī al-Fādil in 1171 to watch a shadow play with him. The vizier, who had not been to a shadow play before, probably expressed religious concerns at first, but was impressed because so many people had appeared and disappeared again and after removing the curtain he was surprised because there was only one man behind it hid. The anecdote shows that shadow play under the Fatimids in the 12th century must have been a respectable and sophisticated form of entertainment that even a pious man could expect. Obviously there was an audience enjoying teachings on religion and morals as a drama. The Egyptian Sufi poet Ibn al-Fārid (1181–1235), who recognized the shadow play as a metaphor for the illusory nature of human existence and in his mystical poem Nazm as-sulūk (“The order des Weges ”) explains its symbolic meaning: The shadow figures represent the sense organs, the curtain represents the human body and the game leader the divine soul. Ibn al-Fārid gives the oldest traditional description of the content of the Arabic shadow play. Heavily armed armies rose in the scenes and fought on land and in the water; there were supernatural beings, wild lions, and simple fishermen. The characters portrayed heroic stories as well as everyday life. All this evoked strong emotions in the audience.

According to the historian Ibn Iyas (1448 - after 1522), shadow play was widely known in Egypt in the 15th century . By that time, Egypt had established its own shadow play tradition , which goes back to the Mosul- born ophthalmologist ( al-kahhāl ) Shams ad-Dīn Muhammad Ibn Dāniyāl (1248-1311). Ibn Dāniyāl, who may have been a Christian, settled in Cairo around 1267, at the time of the Mamluk Sultan Baibars I (ruled 1260-1277). With the Sultan's official permission, Ibn Dāniyāl ran a medical practice at Bab al-Futuh in the old town. He also served several regents as court poet (after Baibars I, among others, the Sultan al-Ashraf Chalīl , ruled 1290–1293, and the Emir Sayf ad-Dīn Salār, † 1310) and acted as a presenter of shadow plays. Of the pieces he wrote for the shadow play, three have survived that date from Baibar's time. They represent the oldest known Arabic shadow plays. Their language was a classic Arabic and - depending on the character of the characters involved - sometimes colloquial and interspersed with personalities or in fine prose.

After the 13th century, isolated references to the Arab shadow play emerged. Ibn Iyas, who mentions shadow plays several times, also reports that Sultan Jaqmaq (1438–1453) ordered all shadow play figures to be burned and that a devout Muslim was not allowed to see the performances. In the course of the 16th century, the shadow play seems to have lost its importance in Egypt, but the Turkish Karagöz developed at the beginning of the same century . In 1517 the Ottoman Sultan Selim I conquered Egypt. It is reported that Selim saw a shadow play in Cairo in which the execution of the last Mamluk sultan, Tuman Bay, was re-enacted. Selim is said to have been so enthusiastic that he took the demonstrator with him to Istanbul. This story is cited as the beginning of Karagöz . In the piece, the rope on which Tuman Bay is hung breaks twice effectively. Such performances aimed at the audience's greed for sensation were probably the reason for Sultan Jaqmaq to forbid the shadow play as a whole because of “immorality”.

The Karagöz has been part of the courtly entertainment culture in the Ottoman heartland since the 16th century and gradually spread to the areas conquered by the Ottoman Empire. In the Maghreb it existed in the 19th century and regionally until the beginning of the 20th century as a crude popular entertainment. The renaissance of the Egyptian shadow play in the second half of the 19th century was a development independent of the Maghreb countries that lasted until the middle of the 20th century.

Performance practice

In the 13th century, the poet Ahmad al-Bayrūtī referred to the box on the right-hand side, in which the figures are kept ready at the beginning of the performance, as the womb, and the box on the left-hand side, which is used to hold the discarded figures, as the coffin. Through this metaphor he elevated the shadow play to the stage of the world. This arrangement was also used by Ibn Dāniyāl, who kept his figures not in boxes but in baskets ( safat, plural asfāt ). The shadows of the thin figures made of dried animal skin were thrown against a white curtain ( sitāra , also sitr, izār or shāsch ) with the light of a flickering oil lamp ( fānūs ) or candle ( shamʿ ) . Temporary stages for outdoor performances required at least one larger box in which the puppeteer ( muqaddim ) acted invisibly. Stationary stages had a wide curtain that separated the audience and the projectionist. In the 18th and 19th centuries, there were makeshift stages outdoors in marketplaces, in coffee houses, occasionally in private homes or in palaces. The shadow images only work when the surroundings are completely dark.

The Ottoman figures of the 18th / 19th centuries Century are about 30 centimeters, the older Egyptian figures over 60 centimeters up to half life size. They are cut out of thick animal skin dyed black and decorated with dashed lines and geometric patterns. In some valuable figures, some cut-out areas are backed with a thinner, painted skin in order to create translucent, colored areas. Since the thin, colored areas are much more sensitive, they were often lost in older figures. Around 1900 the figures were held against the curtain with playing sticks about one meter long (made from the ribs of palm leaves). The tips of the rods are inserted in the figures in circular holes that are reinforced by pieces of leather sewn on both sides. You can move in all directions. A very large figure or a figure with moving parts needs two holes to hold in place. Moving parts are tied together by threads.

The preface to the first of the three pieces Ibn Dāniyāl received says that the author wrote it because his friend - a shadow play demonstrator - complained that people had complained that the shadow plays were all so boring and repeated over and over again . The introduction also shows that a shadow player creates his own figures and arranges them in the box in the order in which they appear. Poems from the 15th century suggest that women (once a slave is mentioned) also performed shadow plays in front of a male audience.

Three pieces from Ibn Dāniyāl

The book with the three pieces ( bāba , Pl. Bābāt ) Ibn Dāniyāls is known under the title Kitāb tayf al-chayāl and is preserved in four manuscripts. The pieces appearing in this order in all manuscripts are called Tayf al-Chayāl ("The Shadow Spirit"), ʿAdschīb wa-Gharīb (two proper names, "the startling preacher and the stranger") and al-Mutayyam wa al-Daʾiʿ al- Yutayyim. The latter is a burlesque about love-hungry Mutayyam, who is drawn to the handsome younger Yutayyim. The external framework of the three pieces is the same: They are set in Cairo in Ibn Dāniyāl's time and revolve around everyday things about which the narrator ( ar-Rayyis, “captain”) reports in the form of the puppeteer. The narrator advances the action as an outside commentator, and by interpreting, he may be expressing the writer's opinion. Occasionally, he also actively intervenes in what is happening. The protagonists are all selected from the lower classes of society because - as Ibn Dāniyāl once had the narrator say - there is a hidden truth in each figure. Ibn Dāniyāl speaks of the representativeness of the theater. The shadow play figures belong to the realm of illusion and are real at the same time, because each could contain a real person. The audience is attuned to this special atmosphere and recognizes the hidden invitation to draw parallels between the characters and the outside world.

The 828 AH (1424 AD) oldest, dated Istanbul manuscript (A) is the most extensive with 364 pages in a wide font and contains sections that do not appear in the other copies. It served as an essential basis for Kahle. The Escorial manuscript (B), dated 845 AH (1441/42 AD), is narrower and consists of 126 pages. The undated Taymurya manuscript (C) from Cairo, probably from the 16th century, with 134 pages has numerous gaps in the text ( Lacuna ). The fourth manuscript (D), dated 998 AH (1590), was discovered by Jörg Krämer in the Azhar library. In this more than half of the second and third pieces are missing.

First piece

The first piece, which gives its name to the entire trilogy, is the longest and most mature. Tayf al-Chayāl is the name of the main character, like the title, who, according to her name, promises a story from the shadowy realm and at the same time from the Cairo of that time in the prologue. Tayf al-Chayāl greets the narrator, performs a dance customary for shadow theater and thanks God with a conventional prayer. In the next scene, Tayf al-Chayāl turns to the audience, tells of his vicious life so far, which he has now renounced and that he came to Cairo to find his friend Amir Wisal, whom he knew from earlier times in Mosul . He says that Sultan Baibars ruthlessly acted against all pleasures in life and forbade the consumption of wine. The Satan responsible for the sins is now dead, Tayf al-Chayāl believes, which is why he sings a long homage to Satan ("our master Iblis ") and in it expresses his longing for the forbidden things. Iblis is given the role of spiritual leader in the underworld, as an underworld counterpart to the “ sheikh ” of a tarīqa . It is the motif of a perverted religious sphere that shows up in other places in the text as a struggle between two opposites. Amir Wisal is now called, who promptly appears as a soldier ( jundi ). Amir Wisal talks extensively about his wild past, about love adventures with both sexes and without leaving out a slippery detail. He advises Satan to leave Egypt in order to avoid punishment from the severe sultan.

Amir Wisal now decides to give up his previous dissolute lifestyle and start a household. Because Amir Wisal appears as a (pseudo) prince, he has a secretary who takes care of his finances (a Copt ). The secretary adds up his property and property, which consists only of graves and the ruined area of Old Cairo. It becomes clear that Wisal is a foolish anti-prince. When Tayf al-Chayāl hears the change of heart, he is dismayed at the decision, which also calls into question his own dissolute life. Umm Raschid, an elderly matchmaker, is called in to find a wife for Amir Wisal. Umm Raschid explains that she has just the right woman ready: young, pretty, divorced from her violent husband - and lesbian. Wisal's problem is to get the money together for the wedding. When Tayf asks him where his many horses, camels and donkeys have gone, Wisal says in rhyming puns that he spent all of his fortune on alcohol. Even his only remaining horse fell ill and died of exhaustion. Well, says Wisal, he wants to get married in order to escape the prostitute and to become an honest citizen.

Umm Raschid shows up without being called, announces the big wedding party and warns Wisal to have the money ready for the chapel. The bride has traveled with her entire family, including a boy who turns out to be her grandson and possessed by the devil. So the bride is that old and incredibly ugly, as Amir Wisal discovers when he lifts the veil and she gives a donkey scream. A lot of obscene details adorn the activities. The deception was the mediator's revenge against the men in general for their bad behavior and against Wisal in particular. The enraged Wisal threatens to use his military authority and demands the punishment of the mediator and her husband Aflaq. Aflaq is summoned, a miserable, forgotten old man who can only remember his youth and who dyed his hair to look younger. Aflaq can report that his wife just died at the hands of the incompetent doctor Yaqtinus. Doctor Yaqtinus is summoned, confirms the testimony and adds that Umm Raschid died in a brothel. The death of Umm Raschid causes the two friends Wisal and Tayf al-Chayāl to show repentance and go on a pilgrimage ( Hajj ) to Mecca.

The plot around the central character Prince Wisal is organized in a somewhat dramatic way. The arrival of Wisal in Cairo represents a turning point in his life and historically coincides with the seizure of power by the Mamluken Baibar. The staging follows a simple pattern in which the characters appear at Wisal's request to Tayf and then at Tayf's request. Only Umm Raschid comes by itself (undesirably). The characters are depicted in a more complex way, especially Umm Raschid. She is a puff mother with a passion for her business, a talkative matchmaker and at the same time keen on her material advantage. The language dialect is carefully tailored to the characters.

The complete abandonment of moral categories is also characteristic of medieval European literature on fools, which is often accompanied by physical and moral deficits. In a coarse form, jokes paired with obscenity appear in early Greek literature and in a more refined language, for example in the novel Satyricon by the Roman Titus Petronius in the middle of the 1st century AD. In Arabic literature, this phenomenon is characteristic of the period between the 9th and 14th centuries.

The piece does not move only in the lower sphere of worldly pleasures. The aspect of death sounds subliminally with the naming of the graves in the enumeration of the - nonexistent - possessions of Wisal. The death of Umm Raschid causes the two main characters to go on a pilgrimage to Mecca. This is where the religious and moralizing component of shadow theater becomes apparent.

Second piece

In contrast to the first, the second piece ʿAdschīb wa-Gharīb almost completely dispenses with an action. It consists of a sequence of scenes with characters embodying different characters and activities and linked by the figure of Gharīb. The names ʿajīb and Gharīb stand for two different social groups. After a short prologue by the narrator, Gharīb (“the strange one”, “stranger”) appears, whose name is a play on words and denotes his belonging to the lower class of beggars , crooks and charlatans of all kinds, who formed the fringe group of the Banū Sāsān in the Islamic Middle Ages . The Banū Sāsān - "descendants of the Sasan" because they traced their ancestry to a legendary Sheikh Sāsān - were a community of like-minded people who roamed about as tramps. Banū Sāsān have been handed down as a subject in early Islamic and medieval Adab literature. Gharīb, looking back wistfully, tells in all details of his enjoyable life, which mainly consisted of alcohol and sex. He explains why, for lack of alternatives, he and his allies have become con artists who have to make a living this way.

To make his methods clearer, he gives the narrator some disguises with which he succeeds in relieving people of their money. These include demonstrations with dancing bears , dogs, monkeys, goats, elephants and appearances as snake charmers , tightrope walkers, sword swallowers, quacks , amulet dealers, teachers and preachers. Gharīb is now withdrawing to provide a stage for those characters. Each of these traders introduces themselves and gives an insight into their work in the language that is typical for them. The preacher appears first, a certain ʿAjīb (ʿAjīb ad-Dīn, "the strange, amazing one"), as a well-known preacher was probably called at that time, followed by all the others. A camel guide concludes. Gharīb closes the piece with an epilogue.

The characters appearing are typical of the literature on the Banū Sāsān from the 13th century, as Clifford Edmund Bosworth (1976) notes. They paint a lively picture of everyday market life in Cairo. The characters' language levels are very different: while the elephant handler and the lion tamer get by with a stanza of four verses, the snake charmer and the astrologer, for example, explain their refined persuasion skills over several pages. The figures move up and down without interacting. Together they represent the aspect of the foreign: They are outsiders of society who, as Banū Sāsān, have found their own identity together. If the last line in the prologue, which consists only of the repetition of the word gharīb , has a meaning, it should refer to the topic of strangeness. ʿAjīb represents the educated class and in this respect corresponds to Hacivat, the partner of the popular, uneducated Karagöz. ʿAjīb - Gharīb and later Karagöz - Hacivat are opposing characters in comic roles who have found a number of successors in the Arab theater. These include the master Sayyid and his servant Farfur in Egypt (in the play al-Farafir by Yusuf Idris , 1964) and in Syria the comedy by Husni and Ghawar (formally based on Laurel and Hardy ).

Third piece

The play al-Mutayyam wa al-Daʾiʿ al-Yutayyim (for example, “The man in love and the lost who awakens passion”) has a plot that is difficult to reproduce because several manuscripts have survived that differ greatly in text. After the narrator has greeted the audience, a desperate Mutayyam appears, who tearfully recites his lovesickness as a poem. Then, turning to the audience, he reports that he has come from Mosul and tells of his love for a young man with whom all other men are in love because of his beauty - which he recognized in the public bathhouse ( hammam ). This is followed by a love poem ( muwaschschah ) to the young man. When he finishes this, a misshapen man appears, making unsavory noises, who claims to be the former lover of Mutayyam from Mosul. He accuses Mutayyam of leaving him. Mutayyam declares the relationship has long since ended and asks him whether he has seen Yutayyim or his servant Bayram by chance, without revealing his passion for them. Mutayyam tells of the first encounter with Yutayyim in the hammam, how he fell on the floor and Yutayyim helped him up.

The young Bayram tries with words of praise to interest Yutayyim in the loving Mutayyam: Both have in common an enthusiasm for animal competitions. When Mutayyam heard this, he was delighted and began to sing. Yutayyim soon appears and joins the singing. In alternate chants they praise the advantages of their fighting cocks, which inevitably leads to a cockfight that Yutayyim's cock loses. The subsequent fight with billy goats also loses Yutayyim's animal, but his ox wins in the next fight. Mutayyam has his inferior ox slaughtered and a feast of wine and delicacies prepared for a large number of men who, on the occasion, engage in all kinds of sexual activities until they fall asleep drunk. The angel of death appears in the middle of the action, waking the sleepers and sobering them. Time for Mutayyam to repent and humbly ask God for forgiveness. The play ends with Mutayyam's funeral. With his death, Mutayyam paid the highest price for his immoral way of life. Because of the morality expressed in this ending, Muhammad Mustafa Badawi (1982) recognizes a parallel between the third piece - as well as the first - to the moralities that were performed in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries.

The third piece is the shortest, although it features around 22 people and a few animals. Cockfighting was a popular pastime at that time, which was pursued on the street and in arenas. The audience also has the opportunity to take sides with one of the fighters during the shadow play animal fights and the game captain has the opportunity to improvise. The great structural differences of the three pieces show Ibn Dāniyāl's endeavor to counter the existing shadow plays, which the audience was bored with, as much new as possible. The combination of rhyming verse and prose speaks for the development of Ibn Dāniyāl's shadow play from the Arabic prose form maqāma . In the opening of the third piece, the narrator refers accordingly to the figure Ibn Hammām, the educated narrator in al-Hariri's (1054–1122) rhyming prose. Ibn Hammam's partner is the vagabond Abu Said, who gets by with a lot of wit and little virtue. The models of the two characters are the aesthetic al-Hisham and the crook Abu l-Fath in the stories of Al-Hamadhani (968-1007). Stage directions are integrated into the text, which in its structure corresponds more to a narrative divided into long speeches than to a drama. Since shadow plays from the 11th / 12th We can only speculate whether similar popular vagabonds as in the shadow plays of Ibn Dāniyāls and the Maqāmāt already played a role. Richard Ettinghausen (1962) was the first to notice a relationship between the two literary genres. The Maqāmāt of al-Hariri, like the derived shadow plays, often contain a satirically exaggerated consideration of society and a moral conclusion.

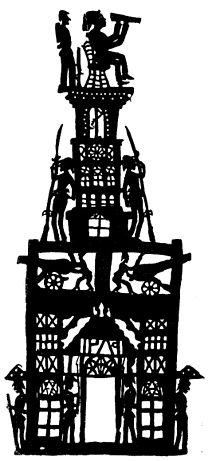

In addition to the literary relationships between al-Hariri's Maqāmāt and shadow play poetry , the shadow play figures also had an influence on the book illustrations. The educated and well-to-do upper class, with whom al-Hariri's work was very well received, created a demand that kept many copyists and illustrators busy. For some, the shadow play figures made in Mamluk Egypt served as the basis for their elaboration of al-Hariri's texts. The people of the Maqāmāt (Austrian National Library, Vienna), dated 1334, are located within a frame that is reminiscent of a theater stage with side curtains. The figures themselves are stylized and filled in as an ornamental surface within a sharp contour. The most famous maqāmāt illustrator al-Wasiti used a more plastic style . His miniature for the twelfth maqāma shows a pub scene typical of the 13th century. Al-Harith can be seen standing upright in profile in the right center of the picture. His posture with an outstretched hand is reminiscent of a shadow play figure, while the other equipment details belong to the canon of illumination. From the middle of the 12th to the middle of the 13th century, Persian ceramic bowls have also survived, on which jumping male figures are painted in profile with black paint on a turquoise or light background, presumably based on the model of shadow play figures. Typical similarities that can be found in Persian ceramics and in book illuminations include an unusually long nose, a narrow forehead, protruding frizzy hair or long, tapering hair.

Alexandria lighthouse

Ibn Dāniyāl's introductory remarks on his three pieces show that his shadow plays were not the only ones back then, but that there must have been shadow plays for a long time before him, of which nothing has been handed down. According to Paul Kahle (1930), a manuscript from Cairo could contain a fragment of a shadow play created at the same time or an even older shadow play. Paul Kahle acquired this manuscript in 1907 from Dervish el-Kaschasch, the son of the shadow player Hasan el-Kaschasch, translated and analyzed the pieces it contained. The manuscript consists of 240 sheets, which were obviously worn out from use in demonstrations.

The title of the first sheet is dīwān kedes ("shadow play collection"); According to the date on the last page, the manuscript was completed in 1707. The compilation of the collection was probably done by the named Raʾīs Dāʾūd al-ʿAttār from the village of al-Manāwi south of Cairo (called Dāʾūd al-Manāwi). A large part of the poems Dāʾūd wrote himself, the rest are from other authors, of whom he names two. From the context it follows that one of the authors named, of whom eleven poems are included, was Dāʾūd's teacher. Paul Kahle believes it is a given that Dāʾūd did not make the copy of 1707 himself - then the stated authors must have lived in the 17th century, but lived at the time of a Sultan Ahmed mentioned. Of the three Turkish Sultan Ahmeds, only Ahmed I (r. 1603–1617) comes into question because under him the vizier Öküz Mehmed was Pasha of Egypt from 1607 and was appointed admiral of the Turkish fleet at the end of 1611. On June 30, 1612, Öküz Mehmed Pascha celebrated his wedding with great pomp in Constantinople . Presumably there were also some shadow actors among the ambassadors from Egypt who beat kettle drums ( naqqāra ) and acted as jokers during their performances and processions . Kahle also concludes that Dāʾūd, as a master of shadow play, belonged to the Egyptian delegation in Constantinople and thus spent most of his life in the second half of the 16th century. His teacher must therefore have been active around the middle of the 16th century. As a result, some of the poems built into the shadow plays come from this period. Kahle believes that the lighthouse game contained in the collection is even older because of its content, as it contains a vivid description of Pharos of Alexandria , who was largely destroyed by an earthquake between Ibn Battuta's first and second visit (1326 and 1349) has been. This suggests that the first version of the piece existed before the mid-14th century.

According to Paul Kahle, the around 80 shadow play figures belonging to this lighthouse game, which he acquired in Cairo in 1909, allow a further time determination. Some have a specific Mamluk coat of arms that was only used between 1290 and 1370. For the shadow play figures, some of which were preserved from the first half of the 14th century, Kahle recognizes a corresponding piece from this time, whose origins could be in the 12th or 13th century.

Kahles early dating of these shadow play figures is called into question by a tiny detail of one of the figures. The figure represents a Nile ship ( Dahabije ) with passengers. One of the passengers, the Pasha seated in the middle, leads a hose to his mouth, which ends at the bottom in a vessel that is clearly recognizable as a water pipe. The tobacco plant only became known in the Old World with the discovery of America. In Islamic countries, smoking utensils have appeared in archaeological finds since the end of the 16th century. Until then, hashish and other intoxicants were chewed or taken as liquids. Smoking is only mentioned in literary sources from the Ottoman period. Consequently, this figure could be an Ottoman imitation of an older model, which makes the dating of the figures uncertain overall. It is also unclear whether they all date from the same period. Kahle met the objection with the tobacco smoker as early as 1911: water pipes with tobacco did not appear until the middle of the 17th century, but hashish was smoked at least in Persia. Kahle believes it is most likely that, in accordance with Chinese tradition, it is an opium smoker, because hashish was consumed by the common people rather than by a pasha. Opium was grown in large quantities in Upper Egypt, as has been reported since the 6th century.

The play "The Lighthouse of Alexandria" ( Li'b al-Manar ) plays its alternative title "The war against the foreigners" ( Harb al- Ajam ) corresponding to a time when the Christian crusaders a threat to Muslims in the Levant constitute . Specifically, as a historical experience, it can only be the crusade against Alexandria carried out under King Peter I of Cyprus in 1365, which was processed in the shadow play.

After an only fragmentary preface, the narrator ( al-Hāziq ) describes the beauty of the lighthouse (Section 3. B, classification by Paul Kahle, 1930) and immediately gets into a comic dialogue with ar-Richim (the clown), who Shout appears. The narrator jokingly calls the fearful ar-Richim a lion who drives away enemies and devours their hearts. The person addressed in this way honestly admits that he will hide behind the door of the house during the next fight. The narrator continues (in 4. Ba) with the detailed description of the architecture of the lighthouse and then moves on to a patriotic homage to his own fighters, who are vastly superior to the attacking unbelievers (Christians). This is done in the form of 24 stanzas of four verses each. The first three verses of each rhyme with each other, while the fourth verse ends in the overall rhyme -āh . The last four stanzas are largely missing.

In the following, fragmentary poem (5th C and 6th Ca), the narrator asks the clown to climb the lighthouse to look for the enemy. Its despondency annoys the narrator. In ten stanzas of five verses each (7th B), the narrator again admiringly describes details of the lighthouse, the fighters gathered there and their weapons. So it goes on in the next twelve stanzas of four short verses each (8th Ba). The arrival of a Moroccan (13th D), a merchant who had been trading in Venice and has now come to warn the Muslims of an impending attack by the crusaders, brings new content. The narrator then calls his brother Maimūn to lead the men into battle (15. E). A messenger from the Christians appears in a short, strophic fragment, trying to persuade the Muslims to give up without a fight (17. F). In addition, the Christian messenger tries in vain to persuade ar-Richim to overflow by promising him riches and his daughter Būma ("owl") to wife (24th J). But since ar-Richim is hungry, he lets himself be lured onto the Christian ship with the promise of good food, where he meets the brave fighter Herdān, who was taken prisoner (27th L). The Christians refuse to release Herdan in exchange for a reward offered by ar-Richim. Herdān asks to be forcibly set free. Then it comes to the fight for his release. A scene written by Dāʾūd al-Manāwi consists of 18 stanzas of eight short verses each. Verses 1–3 and 5–7 rhyme with each other, verses 4 and 8 end with the main rhyme (28th La). A variant of this scene by an unknown author has the same meter (29th La). The Muslims won the battle (30th M), the Banu al-Asfar (Byzantines, in Mamluk times generally infidels, crusaders) are all in chains. The piece ends with verses in which the victory over the Christians is celebrated and the lighthouse is praised again (33rd C).

Throughout the text, incoherent sections are repeatedly interspersed and the main story is held up by numerous repetitions. This may be due to the missing parts and the fact that scenes from several authors and from different times were put together. Nevertheless, the piece thrives on the interplay between the proud proclamations of the heroes and the fearful posturing of the fool. The joke also includes the pronunciation errors of the foreign, Christian characters. On the other hand, the differentiated handling of different levels of language and a finer representation of character that exist in Ibn Dāniyāl's pieces are missing.

The crocodile game

"The crocodile game" ( Liʿb et-Timsāh ) belongs to the more than ten medieval shadow games that the Egyptian scholar Ahmad, along with "The Lighthouse of Alexandria", "The Boat", "The Pilgrimage", "The Bath House" and "The Coffee House" Taymūr in one volume (Cairo, 1957). According to Taymūr, the crocodile game was particularly popular because of its old age and the fine dialogues in the poem form Zadschal . After the shadow play collection ( dīwān kedes ) acquired in 1907 , Paul Kahle came into possession of two further manuscripts in 1909 that contain fragments of shadow plays. One manuscript with several shadow play poems on 128 sheets was probably written by its author Dāʾūd al-Manāwi himself at the beginning of the 17th century, the other manuscript with 25 sheets comes from an ʿAlī an-Naggār, of whom nothing is known. Both manuscripts contain poems on some pages that belong to the crocodile game. Each zadschal at the beginning of a shadow play scene consists of an opening chorus ( matla ) of two verses, followed by stanzas of five double verses each. The penultimate stanza usually contains the praise ( medih ) of the prophet and the last stanza the name of the poet.

The characters appearing include the narrator (al-Hāziq), the clown (ar-Richim), the cat father (Abuʾl Qitat), a Fellache named az-Zibriqāsch with his wife and child, another clown, a fisherman named Sheikh al-Maʿāsch , a black security guard, a Moroccan magician with his companion as well as several fish and a crocodile. After the narrator's prologue, the Fellache answers and asks for forgiveness for his sins. He has given up farming and stumbled upon fishing while looking for another source of income. Because he is so clumsy about it, he falls into the water and has to be rescued by the narrator, who obviously has already had similar experiences with this fisherman and is now starting a dialogue with him. Through the narrator's mediation, the fisherman and the fellah meet. The fisherman tries to teach the farmer how to fish properly. The next time the fishing rod is cast, a crocodile comes and swallows the would-be fisherman, with only the head sticking out of the crocodile's mouth. Now ar-Richim appears and begins a pitiful, comical dialogue with the Fellachen. The Fellach's wife and his little son soon join in the complaint. The fisherman chases the woman away and finds help, initially in the form of the black guard, who only manages to be swallowed by the crocodile himself. Then comes the Moroccan magician who, with the help of another Moroccan and by asking Allah and his prophet for assistance, and with smoking incense and his magic, gets the fellahs and blacks out of the crocodile's belly. With that the piece ends happily. The two Moroccans march away with a triumphant song and the crocodile on their heads. The Fellache is a good-for-nothing and at the same time a pitiful person who can only be saved with supernatural powers. The audience has enough room for interpretation for hidden allegories.

Egyptian shadow theater at the end of the 19th century

In the Ottoman period, the widespread shadow play in the Arab countries was called Karaguz ( karagūz ), in the Egyptian colloquial language Aragoz ( araʾōz ), derived from Turkish karagöz ("black eye ", because of the gypsy origin of the main character) or from Qarāqūsch, one because of its dictatorial Hardship feared minister in Cairo under Saladin or his uncle Schirkuh in the 12th century. The new shadow play figures of the 19th century in Egypt are influenced by the Turkish, they sometimes wear European clothing and fight with European weapons. What was performed in Istanbul in the 19th century, however, was not actually a Turkish shadow play, but corresponded to the cultural mix of the multi-ethnic state, which was reflected in the various dialects, language and social levels of the characters.

The pieces listed under the name Aragoz in Egypt in the 19th century originally came largely from the Turkish repertoire. Only the Ottoman shadow play figures had developed into hand puppets in Egypt . The Egyptian Aragoz is therefore a stage play with hand puppets without a screen, which mainly delighted children until the 1970s. In the early 1990s, hand puppetry came back into fashion at children's birthdays for wealthy Egyptian families.

From the time of Ibn Dāniyāl to the 17th century, no shadow plays from Egypt have survived, although it is proven that shadow plays were also performed in the centuries in between. After the subsequent decline of the genre in the Arab countries, where it only appeared as Karaguz in the lower classes of the population, a revival of the Egyptian tradition followed in Egypt in the second half of the 19th century, independently of the Turkish shadow play, which the shadow player Hasan el- Kaschasch († 1905) is to be thanked. He looked for the remains of old shadow plays in the area of the Nile Delta and found a manuscript from 1707, which he used as an essential basis for his performances. This manuscript (with the name dīwān kedes in the title) was acquired by Paul Kahle in 1907 from the hands of his son Dervish el-Kashash. Hasan el-Kaschasch brought the pieces contained therein into a version that seemed appropriate for the audience of the 19th century.

Alexandria lighthouse

Kahle wrote down the text of Hasan el-Kaschasch's new version of the lighthouse play in 1908 after the performance of his son and in 1914 after the dictation of the shadow player Ali Muhammad, who was a student of Hasan. There were considerable differences in content. The attackers in the new version are no longer crusaders, this time the word ʿadscham in the title Harb al-ʿadscham is understood as a Persian . Since the Persians from the east could not attack across the Mediterranean, the lighthouse from Alexandria is moved to the Red Sea in front of the city of Suez . There, the lighthouse in the text has become a high scaffolding, the character of which nevertheless resembles the historical lighthouse. This lighthouse was built by a tower keeper ( nadurgi ) named Adama, a European in the service of Egypt. The lighthouse, one of the oldest figures in modern Egyptian shadow play, was built in 1872. The figure shows that a pre-Islamic monument still had a religious significance in the 19th century and was considered a shining symbol of Islam.

Adama is also the supervisor for the construction of a warship, the main scene in the play. The lazy craftsmen, who cleverly avoid any work, take care of the humor. As soon as the cannon sounds for lunch break, they lie down to sleep next to their work. For Adama, who speaks Arabic with a European tongue, keeping the workers engaged is a special task. Finally the ship was finished. Six Persians now appear one after the other and recite a poem in order to gain entry into the city. They correspond to the Moroccan of the older piece, who came to warn the Alexandrians of the approaching Crusaders. But these strangers come with hostile intent. As soon as they are in town, they destroy the warship. In the next scene, a sea battle takes place, at the end of which an Egyptian ship named "The Victorious Raven" ( al-ghorāb al-mansūr ) defeated the enemy ships.

Not all figures match the modified content of the piece. Although two Muslim parties are fighting against each other, one of the ships carries Christian crosses on the masts and the other Muslim crescent moons, as they belonged to the text versions of the 16th century. The old lighthouse can still be seen in the outline of the figure, although the text speaks of a scaffold. The content is essentially presented in poems with different numbers of stanzas. The poems in Hasan's pieces do not always fit together seamlessly, as he adopted them from different authors from different times. The beginning ( matla ), which consists of two verses with the main rhyme , is followed by stanzas whose first verse has a special rhyme and the last verse has the main rhyme. The penultimate stanza serves to praise the prophet, in the last stanza the poet gives his name. Often a song sung follows a poem spoken. The melody and rhythm of the song are usually given at the end of the previous poem. The language is vulgar throughout. There is also a special language used by the builders, who say, for example, when they want to convey "the employer has come to us": "the strangler is on the lookout".

The crocodile game

In the modern version of the crocodile game, the narrator ( muqeddim ) speaks an introductory poem and in the next scene leads a comical dialogue with the fellah. The Fellache is called Zibriqāsch as it used to be, an ambiguous name. Zibriqāsh wants to catch fish, so the narrator leads him to the Nile. There he casts the line, but unfortunately he is pulled into the water by a large fish and almost drowns. The narrator calls in the fisherman el-Hajj Mansur because he thinks the Fellache should learn to fish first. Zibriqāsch complains to the fisherman of his suffering, who in turn accuses Zibriqāsch of trying to practice a craft without having learned it beforehand. Under certain conditions, the master fisherman agrees to explain how to fish to the Fellach. Zibrikasch agrees to all conditions and throws the fishing rod into the Nile again. A crocodile comes and devours Zibriqāsch until only its head is hanging out. The clown Richim listens to the suffering, speaks of patience and trust in God, but does not want to get involved. After all, he calls Zibriqāsh's wife and her son. This is chased away by the master fisherman, who now takes care of help. He asks a Nubian what his mission would cost. During the price negotiations it becomes clear that the Nubians are considered limited for Egyptians. The fisherman conducts further negotiations with a Moroccan who has entered. Arguing between the Nubians and the Moroccans leads to a dispute in which both of them call in a compatriot on their side. The Moroccans resign to leave the liberation to the two Nubians. They agree on a secret language so that the crocodile cannot understand them. The action goes wrong and one of the Nubians is swallowed by the crocodile. So the Moroccans are being brought back. Their advantage is that they know magic. With their help, a long mantra and incense, they stun the crocodile and pull the two men out of his stomach with ease. On their heads they carry the sleeping crocodile across the canvas.

The last stanza in which the poet mentions his name is:

“And this shadow play had disappeared from our Cairo, until your servant

Ḥasan Kaššâš made his fortune among the men , but he was a servant of the educated, forever.

When your servant Ḥasan Kaššâš loved the art of shadow play, he used to

travel around and he brought it here, you people, he opened the papers, by the truth of God,

the original manâuī on the arts, until my own name became famous and gained prestige. "

The shadow play brought back to Cairo by Hasan el-Kaschasch was continued by some of his students. Around 1950 it finally had to give way to Arab entertainment cinema.

Ottoman shadow theater in Syria and Lebanon

The individual scenes ( fasl , plural fusūl ) of the shadow theater performed in the evenings in the Syrian and Lebanese coffee houses followed the Ottoman tradition up to the 19th century. Their protagonists were called Karaguz and Haziwaz (Aiwaz). The stereotypical opening of each piece and the beginning of the dialogue ( muhavere ) between the two read, spoken by Haziwaz:

"Welcome to my brother Karakôz, the noble son,

whenever you think of him, he appears."

The length of the scenes was very different, short scenes were stretched by inserting mini-scenes ( gharzah , “sewing stitch”) as a dialogue between the two. A manam ("dream") of the Karaguz could be added at the beginning and a niktah was a mostly obscene joke. Karaguz was, as generally, the foolish, simple type and Haziwaz the educated. The few female characters were limited to mothers, wives or prostitutes.

An example of a play with other protagonists is “Das Malerspiel”, published by Enno Littmann in 1918. It is based on a manuscript written around 1900 in the Ottoman dialect of Aleppo (and at Littmann's request in the Armenian script for better transferability ). The characters appearing are the painter (modeled after Haziwaz), his assistant named Ibisch (as a comical figure similar to Karagöz, there is a figure called İbiş, abbreviated from Ibrahim), the painter's daughter, her lover, two customers and two fishermen. Although the conversation between the painter and his assistant is similar to that between Karagöz and Hacivat, there are linguistic and formal differences, especially because the Karagöz typical song interludes are missing. Littmann therefore recognizes a merely indirect connection via the detour of the Turkish folk theater and the folk tale , to the latter the figure of the narrator, actually the praiser of meddah, is a link.

An unusual combination of Ottoman and Persian tradition is a piece that Johann Gottfried Wetzstein recorded and translated into Syriac-Arabic during his time as Prussian consul in Damascus around 1860 , and which was only published one year after his death in 1906. In “The Lovers of Amasia” there are witty dialogues with descriptions from the life of the gypsies, which are similar to the collection of stories The Thousand and One Nights . At the center of the plot is a tragically ending love story, which is a version of the story about Farhad and Shirin in the Persian epic Chosrau and Shirin . Farhad and Shirin feel united in love after they met by chance while Shirin was on a falcon hunt. In order to win Shirin, the daughter of the Sheikh of Amasya (in Anatolia), Farhad has to cope with an almost impossible task as a demand from Shirin's father: break through a rock wall that prevents a body of water from flowing into the city to the dehydrated inhabitants can. Umm Shkurdum, an angry old woman who, as a reward for her mediation services, demands that Farhad be allowed to be close to him as a second wife and is rejected by him, takes revenge for the rejection. When Farhad managed to hit the rock face with his hoe and thus Farhad was welcomed into Shirin's house, the old Shirin's mother said that Farhad was a good-for-nothing and murderer, which the amazed mother believed. Next, she lies to Farhad, claiming that Shirin died. Farhad then takes his own life with his hoe in order to be united with Shirin in the afterlife. Shirin steps up, sees the dead Farhad lying on the ground, recognizes the intrigue, first stabs the old woman, then himself with a dagger, and collapses over Farhad.

Karaguz from the Turkish shadow play is there, together with Ewaz (Hacivat) and two other characters from the milieu of the traveling people. Even if Karaguz and Ewaz repeatedly warn, sometimes jokingly, point out the true character of the ancients, they do not succeed in preventing the misfortune. After all, Karaguz makes sure that the old woman doesn't get away alive in the end. There are some song and dance interludes as well as a final fight between Karaguz and Ewaz, which nevertheless comment on the whole reflected. That the old man, known as the notorious liar, is so easily believed is psychologically improbable and a weak point of the plot.

In addition to the Ottoman repertoire in Syria, stagings of stories by the pre-Islamic Arab poet Antara ibn Schaddad (525–608) were added. Antara emerged from the relationship between a noble Arab and a black slave. He achieved fame as a heroic fighter of his tribe in the Arabian desert and at the same time because of his poetic works in which he depicts the heroic battles. His deeds and the love affair with his cousin Abla Bint Malik were embellished in numerous legends ( hikayat ). In order to be able to marry the Abla as the son of a slave, the “black hero” first gains respect in battle and then obtains permission, for which he has to endure difficult trials. The episodes from Antara's life are gathered in the epic Sīrat ʿAntar , which has been standard literature for storytellers over the centuries until today. After the enthusiasm of European orientalists for the work, which had been inflamed at the beginning of the 19th century, it served as material for Arab writers at the beginning of the 20th century, and later Antara became the forerunner of Arab nationalism. Battle scenes, as they occur in this and other Sīrat from pre-Islamic times, usually formed the end of a shadow play performance immediately before the epilogue.

Shadow players and storytellers ( hakawati ) were preferably part of the entertainment program in Ramadan . They used obscene language at weddings and circumcision celebrations. The verses of Antara were recited in classical Arabic, otherwise the characters spoke the respective regional slang. Both entertainers had to be able to imitate voices and linguistically slip into different roles, even if the language levels were not as sophisticated as in the plays of Ibn Dāniyāl. In the shadow theater, socio-political issues could also be addressed in a satirical way. The socially critical scenes mostly dealt with the poverty of the population, for which the Ottoman rule was held responsible. Turkish soldiers have always been ridiculed. A related satirical medium is the popular farce al-fasl al-mudhik . While storytellers still occasionally appear in the coffeehouses of the cities, the shadow players with their more elaborate equipment disappeared almost completely after the middle of the 20th century.

The Syrian folklorist Zouheir Samhoury saw a performance by the shadow player Abū Sayyāh in Harasta, a northeastern suburb of Damascus, in 1969 or earlier. He claimed to be the last living shadow player ( mumaththil , in dialect mumassel ) of the Karaguz in Syria. All of his professional colleagues died without having trained a student. Until then, the tradition was mostly passed on from father to son.

North African shadow theater

Decline

The North African shadow theater in the Maghreb countries Libya , Tunisia , Algeria and Morocco is related to the Turkish one after a founding legend spread in Tripoli at the end of the 19th century . According to this, a shadowplayer once showed the sultan the mismanagement of his ministers in one piece, whereupon the sultan elevated the man to vizier and the people adopted the illuminating invention of shadowplay. Behind the legend lies the high reputation that a shadow player had at the Ottoman court and the knowledge about the origin of the shadow play, which was widespread among the people of North Africa. In Benghazi at the beginning of the 20th century, ʿAsker Sūsa (literally “soldier of Susa”) was referred to as a dirty word for the former Turkish military and was also the nickname of Karaguz in the sense of “tramp”, “drifting around”.

It is not known when the Turkish Karagöz came to North Africa. Until the 19th century, there were no reports of shadow games in the Maghreb by either locals or travelers. Hermann von Pückler-Muskau first noticed a shadow play in Algeria in 1835. In the second half of the 19th century, other European travelers discovered shadow play performances in coffeehouses and - for example Heinrich von Maltzan (1863) - in shabby stalls in the big cities . Max Quedenfeldt (1890) found six shadow play booths alone on Halfawin Square in Tunis . In 1905, Georg Jacob saw only one shadow player and one more in another part of the city. Rudolf Tschudi met an old shadow player in Tunis in 1936.

The reason for the general decline of the shadow play in the Maghreb was the colonial policy in the French territories , against which the presenters of the shadow play turned with satirical criticism. With some political comments, the screenings in North Africa were a kind of anticipation of the daily newspapers. The French authorities pronounced a general ban on shadow games in 1843, the justification being directed against the obscene content. But it went against the “notorious degradation of the French, whose reputation as the 'occupying power' was undermined by the means of shadow theater.” The main criticism was that children, who mainly comprised the audience, were brought up morally.

A similar ban was issued by the English administration in Egypt in 1908 in order to suppress the discontent expressed there in the shadow plays against the colonial rulers. The ban initially had only moderate practical effects and only led to the disappearance of the shadow play from the public in the individual cities years later and at different times. In Algiers there were only private screenings in 1858, in Constantine a public shadow play is documented in 1862, in Tripoli in 1889 and again around the middle of the 20th century. In Benghazi it was abolished before 1937. In 1955 Wilhelm Hoenerbach found the “last Libyan shadow player” in Tripoli, whom he had his ten-piece repertoire performed.

Performance practice and characters

Like the colonial administration, the explorers of the 19th century complained about the profanity of the language and generally saw the performances in a basement, a shabby booth, and in a filthy neighborhood of the city. According to the descriptions, it was typically a performance space like the one Wilhelm Hoenerbach found in a vault in Tripoli in 1955. This offered space for 15 spectators on wooden benches. The screen was about 50 × 70 centimeters. A candle was used as lighting instead of the usual oil lamp.

According to descriptions from the 19th century, the shadow play figures are 20 to 30 centimeters long and are mostly cut from untanned cowhide, maybe from camel skin and sometimes from cardboard in simple shapes. Some limbs are flexibly bound by threads. The outlines are described by European observers as so rough that the individual figures can only be distinguished by their way of speaking. Only Karaguz can be recognized by his long phallus in figures from the 19th century, like his Turkish model . At the beginning of the 20th century, the quality of the figures seems to have gotten even worse. The costumes correspond to the Maghrebian clothes and clearly distinguish the figures from the Turkish ones. Karaguz and Sleyman (the Turk) wear a jacket and trousers, the other figures wear a cloak ( jallabiya ). Haziwaz (Hacivad, the opponent of Karaguz) wears a crown cap. The particularly high cap of a Haziwaz figure that Hoenerbach saw in Tripoli in 1955 is reminiscent of a Turkish pointed hat ( külah ) and points to a corresponding connection that is otherwise not recognizable in the forms. Other male figures wear a fez , women a pointed hood. The Jew has wrapped a cloth around his fez. The hash smoker holds a pipe upright in front of his torso. Most of the figures are monochrome or have little paint left over.

The Turkish opening figure ( göstermelik ), introductory music, introductory dialogue ( muhāwere ), song and praise of God are missing in the Maghreb. The narrator explains in a few words the first character who sings a melody mostly without text and after a short time gets into the first beatings scene. Karaguz initially names the game to be expected, which is ended after a quarter of an hour by the cleaner Baba Chwaneb, who eliminates all pieces. A continuous plot has been lost in the strong streamlining of the original content. The individual, loosely linked scenes can mainly be assigned to two specific patterns of action. Type A: Karaguz practices a trade that Haziwaz can persuade him to do (gardener, bath house supervisor, rental of swings, fisherman). Type B: Karaguz is on the forbidden paths, he is after the property of other people or a strange wife. In one play, for example, Karaguz wants to penetrate a women's bath.

Characters

As with the Turkish role model, the more deliberate Haziwaz stands behind his moderately clever, often simple-minded and ultimately clumsy partner Karaguz, but the differences are less clearly defined. As there, there are also some special types that differ in terms of physical deviations, speech impairment or foreign origins. The mute just babbles and has some physical ailments as well. The opium smoker sleeps all the time, and because he shares this quality with other characters, he must also be hunchbacked.

The types from the people include, depending on the shadow theater, an Arab, Moor , Maltese (correspondingly Turkish: Christian), Jew, Black (musician), Bedouin (cheater), man from Djerba , European madāma , Turkish soldier or Egyptian : types mainly originating from the Turkish game, which were replanted according to the region. Including some servants, other staff and animals, a set of figures adds up to around 20 to 25 parts.

Karaguz is interested in the common things of everyday life, he likes to eat, is also otherwise concerned about his well-being, flees from danger and uses the fecal language. His phallus, which he used as a stick in a fight, had disappeared at the beginning of the 20th century, but he kept his bald head. Rubbish and beatings are the social lapses that are always described. A comparison of older and younger pieces shows that obscenities and roughnesses are softened. In the older version of the play “Das Badehaus”, for example, the attendant runs her bathing establishment as a brothel and in the revised version she simply manages her bathroom in a messy way. By twisting words, which lead to misunderstandings, in some cases a somewhat more subtle comedy emerges, which, however, is less polished than in the Turkish pieces. Karaguz is not stupid in such cases, but acts stupid to his advantage. After the ban in 1843, shadow theaters that were still tolerated were reluctant to deal with current political issues.

repertoire

Many pieces are based on the principle of row formation, as in the piece “The Swing”, which Georg Jacob saw in Tunis at the end of the 19th century. It is a version of the Turkish piece Salıncak . Karaguz has a seesaw swing and wants to rock the customers. An old man comes and sits on one end of the swing, Karaguz on the other. When it comes to paying, the old man hits Karaguz instead and disappears. Karaguz wants prepayment with the next customer, a soldier. The soldier refuses, swings and hits Karaguz with the side of the saber as he leaves. Such a ranking is also the basis of the "Spiel vom Badehaus" (recorded in 1927). Haziwaz's wife runs a bath house as a brothel. The Arabs, the Indians, the Maltese and finally the Jews are admitted as visitors. Karaguz is unsuccessful and fails when he hides behind the Jew and complains about his disadvantage. The play ends with a beating scene.

In the "Game of the Hindāwi" (recorded by Max Quedenfeldt in Tunis in 1889) the Hindāwi (possibly an Indian) enjoys his wife's singing in the garden. Karaguz comes by and claims this is one of his wives. The Hindāwi chases Karaguz away after the woman denies ever knowing Karaguz. Later Karaguz comes back, kidnaps the woman and takes her to his house. Again he returns to the Hindāwi, who has so far not noticed his wife's absence, and innocently asks about her. The Hindāwi sees through the kidnapping and furiously sends his helpers to bring the woman back. When they reach Karaguz's house, Karaguz hits them all in turn and chases them away. One after the other, the servant, the opium smoker, the mute, the black and the Maltese try to get into the house, but are repulsed by Karaguz, who beats them with his phallus or blows the ashes of the opium smoker's pipe. Only the Algerian manages to use a trick to get into the house, where he doesn't free the woman, but has fun with her. The last to be sent to the house is the seven-meter-long giant Og ben Oniok. He asks Karaguz where Karaguz is. Karaguz realizes the chance of getting away undetected, tells the giant that the Karaguz is inside the house. The giant reaches through the window with his hand, pulls the woman and the Algerian out and carries them away.