Khyal (theater)

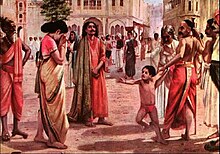

Khyal , also Khayal , is a popular folk dance theater in the northern Indian state of Rajasthan , which consists of a sequence of dialogues, dances and poetic songs performed in prose and whose style developed in the 18th and 19th centuries from the tradition of swang . The entertainment program, which is mostly performed in the open without a stage, took over many content and scenic elements from professional parse theater. The themes come mainly from the popular Rajasthani legends and heroic stories.

history

The word khyal is derived from khel (“to play”, “to act”, “to act” in the general sense) and also denotes - without any connection to it - the style of singing kyal in classical music in northern India. It is possible that the origin of the Khyal theater lies in the poems about historical and mythological figures that were written in the Agra area in the 17th century . At the beginning of the 18th century, these poetry recitals were transformed into a drama in Rajasthan, at least since that time in Rajasthan a mixture of drama, dances and songs known as khyal has been known. In the first performances the emphasis was on poetry contests and less on dramatic scenes.

None of the regional Indian folk theater styles can be traced back further than the 16th century. Khyal is part of a broad tradition known as swang , from which several independent styles have developed: nautanki in large parts of northern India, sang in Haryana , bhagat in Uttar Pradesh and tamasha in Maharashtra . Some in Madhya Pradesh , jatra in Bengal and yakshagana in Karnataka are examples of similar theater styles.

Parallel to the development of the older swang to nautanki and the other regional styles, a stage was added to individual productions by Khyal. A distinction is made between four types of stage in such popular theaters: The simplest performance location consists of a flat surface in the open air, where the audience can sit outside in a circle. The actors move in such a way that they take turns speaking in all directions. A new development of the Nautanki style and some khyal performances is a curtain as a stage background, in front of which the audience sits on three sides and behind which the performers prepare. Next there is a canopy ( mandap , like the Indian temple vestibule mandapa ) resting on four posts , which is open on all sides except for the rear curtain. In the fourth stage of development, a multi-storey building ( attalika ) was created as a stage and backdrop, called mahal ("palace"), with a stage platform in front of the rear construction. Such professionalization was strongly influenced by the European-oriented Parsen theater.

Since the second half of the 19th century, khyal has been divided into the three variants Alibuxi, Shekhawati and Kuchamani . Alibuxi khyal was introduced into Alwar by Ali Bakshi (Alibux), the Nawab of Mandawar . He was a Rajput of the Chauhan dynasty who had converted to Islam , but he was enthusiastic about the ras lila dances and songs in honor of Krishna, which are part of the Hindu bhakti tradition . Ali Bakshi composed a few pieces himself and created a religious form of khyal, consisting mainly of song and dance, which, however, was only cultivated by a few performers after his death and has practically disappeared today. Alibuxi khyal is stylistically similar to nautanki , the dances are related to the north Indian kathak .

Shekhawati khyal is performed by the Mirasis Muslim musicians in Chirawa ( Jhunjhunu District ), who practice a classical style of singing. As Rajputs, they used to sing at the royal courts. Kuchamani khyal in Nagaur district is a more folk style that is about religious or historical narration.

Performance practice

Each style of khyal theater is preceded by a corresponding prelude ( purvaranga ) in the form of a religious homage. Usually theatrical performances begin with the invocation of the good luck god Ganesha . In one type of purvaranga , a man first enters the stage with a broom and sweeps the floor, followed by the water sprinkler ( bhisti ), which sprays water so that the dust settles. Both make their action entertaining by singing and dancing songs on the side. This used to be the usual procedure for preparing theater performances in the ruling houses. Next, the director announces the sequence of scenes and the actors come on stage, ask various gods for assistance in a greeting known as vandana and begin with the actual performance.

Kuchamani khyal , which is rooted in folk music , is the only style that has remained popular to this day, some performers have become known nationwide through dissemination in the mass media and the performances, which are mass-tasted with business interests, attract visitors from further afield. The classic Shekhawati khyal style has taken a back seat .

The performances mostly take place in the open air, a wooden platform ( takhat ) about one meter high serves as the stage . The audience sits on three sides. If a temporary theater building ( mahal ) is erected, it can reach a height of up to six meters. Covered balconies ( jaroka s) protrude from the palace wall , representing different locations of the action. Actors who are temporarily not needed sit down with the musicians at the edge of the stage.

All characters, including women's roles, are portrayed by men. When the troops used to go on tour for months and roam around in camel caravans, the wives accompanied their husbands. Some traveled from Rajasthan to the north of Gujarat .

As in most folk theaters, the accompanying music, which in the khyal consists of kettle drums ( nagārās ) and a harmonium , plays a major role in the staging . Further instruments are a popular variant of the string sarangi , the cone oboe shehnai , a flute, the double-headed barrel drum dholak or the similar dholki and the frame drum dafdi (derived from daf ). Classical ragas are used in the songs of Shekhawati khyal , while the singers of Kuchamani khyal use melodies from folk music.

The plays appear in a similar selection in the Parsen Theater, mostly about the legends of the brave heroes numerous in the Rajasthani folklore. Stories about Amar Singh Rathore, a Rajput who worked at the court of Mughal Shah Jahan in the 17th century, are popular . His will for freedom, when he got into an argument with the ruler and fled the palace by jumping on his horse, is honored in many ways in the traditions.

The love story Dhola-Maru is highly valued in the western part of Rajasthan and in Gujarat and has been told in numerous variations since the 16th century . The poems are performed there by Manganiyar singers or performed throughout the state as khyal. It's about Princess Maru from near Bikaner and the young Prince Dhola from Gwalior . Although they were promised each other since their early childhood, they do not meet until many years later and have to flee into the forest on a camel, where Dhola is fatally bitten by a snake. In the end, through divine providence, they come together.

Other legends surround King Bharathari, who lived in the 1st century BC. BC reigned in Ujjain before he renounced the world together with his nephew Gopichand and became a saint ( Gopichand-Bharathari ).

literature

- Keyword: Khyāl. In: Late Pandit Nikhil Ghosh (Ed.): The Oxford Encyclopaedia of the Music of India. Saṅgīt Mahābhāratī. Vol. 2 (H – O) Oxford University Press, New Delhi 2011, p. 556

- Darius L. Swann: The Folk-Popular Traditions. Introduction. In: Farley P. Richmond, Darius L. Swann, Phillip B. Zarrilli (Eds.): Indian Theater. Traditions of Performance. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1990

- Manohar Laxman Varadpande: History of Indian Theater. Loka Ranga. Panorama of Indian Folk Theater. Abhinav Publications, New Delhi 1992, pp. 162f

Web links

- Khyal, Indian Folk Theater. Indian Net Zone

Individual evidence

- ↑ Swann, p. 241

- ↑ Varadpande, p. 162 f.

- ↑ Swann, p. 241.

- ↑ Lowell H. Lybarger: Hereditary Musician Groups of Pakistani Punjab. (PDF; 1.1 MB) In: Journal of Punjab Studies . Vol. 18, 1 & 2. Center for Sikh and Punjab Studies, University of California, Santa Barbara, Spring 2011, pp. 97–130

- ↑ Varsha Joshi: Rajasthan. A Mosaic of Culture . In: Vijay S. Vyas, Sarthi Acharya, Surjit Singh, Vidya Sagar (eds.): Rajasthan: The Quest for Sustainable Development. Academic Foundation, New Delhi 2007, ISBN 978-8171886210 , p. 357.

- ↑ Varadpande, p. 163.

- ↑ Khyal, Indian Folk Theater. Indian Net Zone