Franz von Lenbach

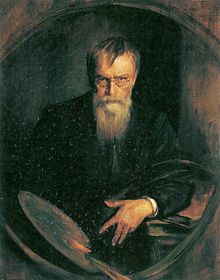

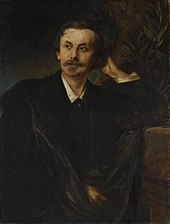

Franz Seraph Lenbach , Knight of Lenbach since 1882 , (born December 13, 1836 in Schrobenhausen , † May 6, 1904 in Munich ) was a German painter .

He became known for his portraits . Among those represented are Otto von Bismarck , the two German Emperors Wilhelm I and Wilhelm II , the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph , Pope Leo XIII. as well as a large number of prominent figures from business, art and society of the late 19th century. He himself was one of the most famous artists in Germany and Austria during his lifetime.

Because of his outstanding social position and his lifestyle, he is referred to in public and by art historians as the “Munich painter prince ”.

Life

Childhood and youth

Franz was the fourth child from the second marriage of the Schrobenhausen master mason Franz Joseph Lenbach to Josepha Herke. The father, a bricklayer foreman who immigrated from South Tyrol, originally wrote himself “Lempach”. In 1820 he was awarded the position of master mason and thus the management of an independent construction company. Since the city expanded rapidly from 1840 onwards, the company was well utilized with orders for house and road construction, both in the city itself and in the surrounding area. Despite having a large number of children, the family achieved civil prosperity and was able to build a stately two-story house.

The father's two first marriages resulted in a total of 17 children, of which only 11 lived until 1844. Franz's mother died in 1844; the father married Elisabeth Rieder in 1845. The only child from this third marriage died 18 days after his birth in 1845.

In October 1848 Franz Lenbach graduated from the six-year elementary school with excellent results, ten times excellent and one very good . His further training initially followed the intention of having him participate in his parents' construction business. He worked early on in his father's business with bricklaying and drawing work. From the end of 1848 he attended the trade school in Landshut, which he graduated with an overall grade of very good in August 1851 . From November 1851 to March 1852 he was training with the building sculptor Anselm Sickinger in Munich.

The father died on April 8, 1852. Joseph, the eldest half-brother from his first marriage, took over the management position in the construction business and the father role in the large family. Franz now worked harder there, trained and was acquitted a year later as a bricklayer .

Training as an artist

From the autumn of 1852 he attended the Royal Bavarian Polytechnic School in Augsburg to take lessons in figure drawing. He graduated with excellent in August 1853 . He used his free time for his own painting experiments. On Sundays he painted oil paintings in nature, in the remaining free time he devoted himself to copying studies in galleries in Augsburg. In 1853 he became friends with the Munich academy student Johann Baptist Hofner . He moved into the attic of his house in Aresing . Together they painted townscapes and made portrait and figure studies in the vicinity.

In January 1854 he was accepted into the Munich Academy of Fine Arts . He completed three semesters in basic drawing before he entered the technical painting class of Hermann Anschütz in 1856 .

During his studies he continued his leisure time painting. He was in Aresing as often as possible to paint with Hofner and later with other academy students. The Aresinger painting school finally gained a certain reputation in Munich, and Lenbach was able to earn a living with his work: his works were often bought for festive and family occasions. A mundane but important source of income for him were so-called shooting pictures: round paintings of the right size that were mounted on the target at shooting festivals. Some of these discs have been preserved, some with a large number of holes.

His peasant genre paintings reveal a rapid development from practitioner to artist: his technique became more secure, his objects became more lively. His work at that time by no means reveals the later portrait painter; rather, they show an independent style of painting that broke away from the conventions of academy painting. In this respect, despite stylistic differences, it is comparable to the open-air painting schools that flourished in France at the same time.

In 1856 Karl Theodor von Piloty was appointed to the academy led by Wilhelm von Kaulbach . Associated with this was an artistic renewal. Piloty countered the literary classicism with drawn through-composed pictures with a conception of art that set accents with an effective color scheme that modulates the mood. This style of painting suited Lenbach; he applied for admission to Piloty's painting class and was accepted there in November 1857.

First successes

Piloty focused on historical and literary subjects in large format images. His student Lenbach tried to meet his requirements and at the same time to use the experiences he had tried and tested in Aresing. With this approach he was successful. In 1858 he was able to exhibit his picture Country People fleeing from a storm at the German Historical Art Exhibition in the Munich Glass Palace and sell it for 450 guilders. He was also granted a state scholarship.

Equipped with these resources, he went on a study trip to Rome from August to November 1858 together with his teacher Piloty. One result of this trip, the painting of the Arch of Titus , he was able to sell to Count Pálffy in 1860, possibly through the mediation of Piloty . He had completed this picture at home in Aresing; for the figurative decoration, young people from Aresingen were his models.

In the summer of 1859 he painted The Red Screen , which critics praised as an early work of German Impressionism . There is an autonomy in the coloring that goes far beyond what Piloty taught him. Despite his growing artistic independence, he remained connected to Piloty and continued to let him advise him with suggestions and suggestions for corrections.

In the late summer of 1859 he went on another study trip that took him to Stuttgart, Strasbourg, Paris, Brussels, Liège, Aachen and Cologne. During this trip, another picture of him found a buyer: his Bavarian farmer , which was exhibited at the Münchner Kunstverein and was created in 1860, was acquired by Albert Havemeyer from New York for 250 guilders. The first commissioned portraits were probably made in 1860 or the year before.

Even while he had become independent as a successful young artist, Lenbach remained solidary to his family. He supported his siblings with errands and cash advances. His younger brother Ludwig's watchmaking business served him as a point of contact through which he could keep in touch with his customers when he was not in Munich. He mediated in the conflict between the older half-brother Franz, who fulfilled his role as head of the family and entrepreneur rather brusquely and authoritarian, and the younger siblings, especially those from the father's second marriage. In 1866 he hired his two unmarried sisters, who were living in dependent positions under difficult circumstances, to run his household.

Teaching and artistic reorientation

Professorship in Weimar

Lenbach's further life benefited from two circumstances: On the one hand, the general upswing in the arts in Bavaria in the middle of the 19th century, supported by the kings Ludwig I and Maximilian II , but also by the artistic sense of the nobility and the upper class. In the middle of the century, a number of art associations and galleries emerged, and works of art met with lively interest and sales. On the other hand, Lenbach, like many of his fellow students, benefited from the support of his influential teacher Piloty, who, with the help of his good connections, was able to put many of his students in good positions.

The Grand Duke Carl Alexander also promoted the arts in Saxony . In June 1860 Lenbach was appointed professor at the newly founded Grand Ducal Art School in Weimar , together with the Piloty students Arthur von Ramberg and Georg Conräder and the Swiss Arnold Böcklin . Lenbach often went out with his students and practiced open-air painting with them, following the Aresinger model. The art historian Walter Scheidig even sees Lenbach as the founder of Weimar landscape painting, which flourished a few years later.

Lenbach became friends with Arnold Böcklin and Reinhold Begas, who was later appointed professor in Weimar . They agreed to meet to study portraits together. Lenbach readily learned from the older Böcklin, adopted methods of contrasting and color grading as well as the art of systematically applied hardness. In doing so, he developed his own portrait style, which placed the personal individuality of the person depicted in the foreground - in contrast to the style practiced at the time, which paid great attention to the social role of the person through carefully arranged items of clothing, accessories and symbols.

Study of the old masters and Schack's copy collection

In April 1862 Lenbach left the Weimar Art School at his own request. In his own assessment, later expressed, he had more to learn than he could teach. He was aiming for another study visit to Italy. “I only stayed in Weimar for a year and a half. The realization that I first had to learn instead of teaching drove me away, as did my longing for Italy. ”When he ended his work in Weimar, he also gave up his landscape painting once and for all.

First he turned to Munich, where he turned to the old masters in copy studies, whose works were exhibited in the Pinakothek . In Munich he met the baron and art collector Adolf Friedrich von Schack . He wanted to supplement his art collection with high-quality copies of works by the old masters - a common practice at the time among wealthy art lovers in Germany and even more so in France. For example, many of the most famous names of the time are in the Louvre's copy registers . The Schack copy collection of 85 paintings, for which Lenbach laid the foundation with 17 works, was one of the most important of its kind, for example alongside the even more extensive, but dissolved collection of Bernhard von Lindenau , the Potsdam collection of Raffael copies and Charles Blancs Paris Musée des Copies .

In November 1863 Lenbach was finally able to leave for Italy, provided with an annual salary of initially 1000 guilders, which was later increased to 1400 and finally to 2000 guilders. By March 1865 he made copies of the Heavenly and Earthly Love of Titian , the Madonna of Bartolomé Esteban Murillo and of Titian's painting Salome with the head of John the Baptist . The choice of the last picture went back to Lenbach himself; Schack also frequently accepted Lenbach's suggestions for later copies.

In April 1865 Lenbach moved to Florence, together with Hans von Marées , who was also supported by Schack and whom Lenbach took into his care at his request. There, in the same year, copies of an individual and a group portrait of Titian, the so-called Young Englishman, and the concert were made . It is assumed that these two pictures had a particularly formative influence on Lenbach, as they create an effective impression of the people portrayed with economical pictorial means. The selection of other pictures that he copied, namely three further portraits by Titian and a self-portrait by Peter Paul Rubens , indicated his incipient predilection for portraits. Only after repeated urging by Schack did he also paint a copy of the Venus of Titian.

Schack valued Lenbach's work very much. Both he and many of his contemporaries even considered them equal to the originals. In the Schack'schen Galerie they hung on an equal footing with contemporary originals, whereby the copies were not listed under the name of the copyist but under the name of the model. If the originals and the copies are placed directly opposite one another, the copy sometimes does not quite come close to the color strength and depth of the original. However, Lenbach often had to copy in cramped conditions and in poor light, and he did not use the same colorants as his role models.

New start in Munich and a trip to Spain

In June 1866 he returned to Munich, rented a studio on Augustinerstrasse and tried to gain a foothold as a portrait painter. He already had good connections with high society, but the order situation was rather precarious. He eagerly advertised to potential customers to sit with him for portraits, worked from early in the morning until late at night; however, paid jobs were the exception rather than the rule.

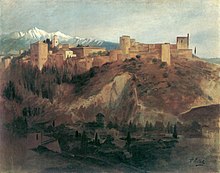

At the world exhibition of 1867 in Paris Lenbach received a gold medal III. Class. In September of the same year he traveled to Spain via Paris to make further copies for Schack. He used this trip to paint copies of two famous representative portraits of rulers. First he dedicated himself to the portrait of King Philip IV of Spain in a hunting costume, painted by Diego Velázquez around 1632 . Then he copied the equestrian portrait of Charles V by Titian. The mighty portrait format picture, 3.36 × 2.80 m in size, was created in 1548 during the Reichstag in Augsburg . As the embodiment of the emperor's claim to power, it is one of the politically most important portraits of its kind; echoes of this model can be found in the baroque portraits of rulers by Rubens and Velázquez. For Schack, this portrait was the first monumental painting in his collection.

While he was copying for Schack in Italy and Spain, Lenbach also worked on his own works with Schack's consent. In June 1868 he returned to Munich.

Rise as a portrait painter

Artistic models

When Lenbach returned to Munich, he began his career as a portrait painter in the narrower sense. According to his own statements, made at a later stage in his life, he followed a firm artistic ideal: In contrast to the classicist painting of his teachers, it was important to him to tactfully depict the individuality of the person depicted. “To do art means to practice tact. With tact, the size, the format of the execution ... is to be selected and recorded ... In life, too, tact is the basic condition of an artistic relationship between people, so to speak. The people who have tact are the true aristocrats of mankind… ”In a sense, the portrait had the task of ennobling both the person portrayed and the artist. This view excluded naturalistic representations of ordinary living conditions and explains Lenbach's departure from his early years. What the French realists such as Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet put into the picture, depictions of poverty and hard drudgery, did not come into consideration as an object of artistic representation for him.

The old masters were decisive in his painting style. Painters like Peter Paul Rubens and Titian were the models who, in his opinion, best portrayed the individual personality. He strove for them to the point of complete imitation of their style. In this backward-looking sense he even saw himself as a revolutionary, he had “nothing less than to throw all modern art over the heap, to at least bring about a revolution in the whole world of painting”.

Social and economic advancement

This was accompanied by his striving for social advancement and his pronounced sense of gain. "In Berlin, I hope, my career begins, 5,000-10,000 florins a year (provided I stay healthy) will probably not be difficult for me to take from the rich ox there." Gradually he was able to gain a foothold; won reputation and orders. The breakthrough came with the international art exhibition in Munich's Glaspalast in 1869, at which leading French artists such as Camille Corot , Gustave Courbet, Charles-François Daubigny and Jean-François Millet were represented. Lenbach received a gold medal.

Lenbach's style of painting met the needs of the emerging upper middle class. In the boom years in Germany and Austria around and especially after 1870, enormous fortunes were created; the bourgeoisie strove for reputation and glamor that could rival that of the nobility, and spent large sums of money on art purchases. Pictures by Lenbach or Hans Makart , which put both the person and their rooms in a noble light, were the preferred choice for many.

In Vienna, the expansion of the Ringstrasse brought with it a great blessing of public and private commissions for artists, from which Lenbach also benefited. In 1870 he stayed in Vienna for several months. This stay brought him an expansion of his relationships; Among other things in the form of long-term friendship with and orders from the Wertheimstein and Todesco families. Via those upper-class families, the doors to the very highest, the so-called first society, finally opened for him : the high nobility up to the imperial family. During those months he also became friends with Hans Makart. He repeated his several months' stay in Vienna every year until 1876. In 1872 he stayed in Berlin for several months.

At the world exhibition in Vienna in 1873 Lenbach was represented with portraits of the two Emperors Wilhelm I and Franz Joseph . The portrait of Emperor Franz Joseph from 1873 is a joint work with Hans Makart and Arnold Böcklin. In terms of its representation, it closely follows a portrait made by Franz Xaver Winterhalter in 1864 , which was very popular at the time. However, critics consider it to be one of Lenbach's less successful works: the indecisive expression and the stiff posture of the person portrayed as well as the unclear room situation and accessories - in contrast to Winterhalter's model - creates an unclear, weak visual message.

Artist community and private life

In 1873 his position was so solid that even the stock market crash on Black Friday , May 8th, and the economic crisis that followed, could not harm him. However, it was during this time that the first criticism from painters and art lovers was also raised. The art writer Adolf Bayersdorfer condemned the Vienna World Exhibition in a series of newspaper articles, denouncing “academism and theater, archaisms and phrases” and “conceitably renowned chic”. Also Anselm Feuerbach judged critically Lenbachs exhibits at the World Expo, "Lenbach in some sound, but it is believed plastered old pictures to see much purpose." In the same year it came to the break with his longtime friend Arnold Böcklin, who in Unlike Lenbach, it had been badly hit by the economic crisis.

However, friendship and recognition prevailed among artists and intellectuals. In addition to the aforementioned Hans Makart, his friends included the couple Cosima and Richard Wagner, Lorenz Gedon , his teacher Piloty, Wilhelm Busch , Paul Heyse , Reinhold Begas , Friedrich August von Kaulbach and Paul Meyerheim , to name just a few.

With his Munich-based friends of opinion among the artists and art lovers, Lenbach joined forces in 1873 in the artist society Allotria , which emerged as a spin-off from the long-established Munich artists' cooperative . Lenbach became its president in 1879. The allotria quickly became a determining factor in Munich's art and social life, and an institution for maintaining contact between artists and well-off art friends. One could not enter the allotria; one was introduced. In addition to visual artists, musicians and theater people, it included civil servants, officers, lawyers and bankers.

From June 1875 to March 1876 Lenbach traveled to Egypt with Hans Makart and other Viennese art lovers. He enthusiastically wrote home his impressions of Cairo street life. “Cairo is fabulous beyond all expectation, one of the 500,000 inhabitants is stranger than the other. ... In the streets, which are countless, it goes on in all the costumes of the world, like an anthill, in Paris or Naples one has no idea about life ”. Two special pictures of this trip have survived: on the one hand, the portrait of an Arab , it shows a relatively young man with a decidedly exotic charisma, proud, presumably stylized facial features and a closed look, and on the other hand, an architectural image that is unique to Lenbach; in warm brown tones with charming light and shadow effects, it shows a palace interior in Cairo .

On the other hand, he was not very lucky in love relationships until well into midlife. Nothing is known of love affairs before his late marriage. Hints in his letters suggest that he also stayed in Vienna so often because he had an affection for Countess Marie Dönhoff, née Principessa Camporeale , an outstanding pianist who was unhappily married to the Prussian diplomat Karl Graf Dönhoff. Lenbach's hopes, however, were not fulfilled; Countess Dönhoff married the later Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow after their marriage had been divorced at the end of 1885 .

At the peak of success

Success in the upper class of society

In 1874 he met Otto von Bismarck , through the mediation of Laura Minghetti and other influential women in society, in Bad Kissingen . This was the beginning of a lifelong bond between the painter and the Reich Chancellor, which has shaped Bismarck's public image to the present day.

In 1882 Lenbach received the Knight's Cross of the Order of Merit of the Bavarian Crown and, as a Knight of Lenbach, was raised to the personal nobility . Lenbach was now a leading figure in Munich's artistic life. As a portraitist recognized and sought after in the upper classes of society, he had achieved prosperity through his art and his skillful interaction with people.

In 1883 he traveled to Rome again, rented a floor in the Palazzo Borghese and set up an apartment and studio there. He was also a fixture in social life there. Lenbach maintained an iron work discipline throughout his life, but a fixed part of his time was now devoted to representing and receiving guests. To do this, he furnished his apartment with precious carpets and furniture, statues and room decorations and employed two servants. On May 1, 1883, on the occasion of the performance of Richard Wagner's Ring des Nibelungen in Rome, the German embassy held an official reception in Lenbach's palace.

In 1885 a portrait of Pope Leo XIII was created. Since the Pope could not or did not want to take the time for lengthy model meetings, Lenbach made use of a photographic template made for this purpose - a technique that he later came back to frequently. The picture is seen by the critics as one of the highlights of Lenbach's work due to the painterly quality and the expressive rendering of the face. For the portrait, Lenbach evidently dealt with the portraits of the Popes by the old masters, namely Titian's portrait of Paul III. , Raphael's portrait of Julius II and especially Velázquez's depiction of Innocent X. were his sources of inspiration. The picture was publicly exhibited in Munich, Berlin and other cities with great attention. Lenbach then donated it to the Munich Church Building Association, which sold it to the Bavarian state government a short time later. In addition to this knee , a number of other portraits of the Pope were created, which were also very well received by critics and the public.

Lenbach stayed in Rome in winter and spring until he gave up the palace apartment in 1887.

Lenbach's Bismarck portraits

According to the Thieme-Becker artist lexicon , Lenbach created around 80 paintings by Bismarck by 1897, as well as a vast number of sketches and drafts. He must have tried hard to get the first meeting in Bad Kissingen mentioned above, as one of his letters to Josephine von Wertheimstein shows. A drawing from 1877, a half-length portrait, is probably one of the first portraits of the Chancellor that Lenbach made. In 1879 he stayed at the Bismarck house for eight days. On this occasion the famous, much replicated portrait was created, which was bought by the German National Gallery in Berlin in 1880 and which was destroyed in World War II. In the course of time Lenbach became a frequent guest in the Bismarck family; he was included in family life and came to visit for Christmas parties and birthdays.

Lenbach's depictions of Bismarck are characterized by a rich variety, both in terms of the situational environment and the nuanced states of mind depicted. While other painters, for example Anton von Werner , show Bismarck exclusively as a politician, as a speaker in the Reichstag or in historical pictures, Lenbach also depicted Bismarck as a private citizen - in knees, half-portraits and half-length portraits. Bismarck is dressed in uniform, frock coat, coat or hunting suit. Most of the time, the image is focused on his face emerging from the dark. Sometimes the picture shows a relational object in Bismarck's hand. An example of this is a finely worked picture from 1884, which shows him reading a document that he brought close to his eyes. A well-known picture of this kind from 1890 shows him presenting his resignation with a resigned but open look.

The portraits can be grouped by type according to the time they were created. In the 1880s the portraits show the Chancellor predominantly as a statesman in civilian clothes, in a frock coat and waistcoat or in a coat. From 1890, depictions of him in uniform increased. It is possible that Lenbach, who was violently indignant about Bismarck's dismissal in 1890, wanted to emphasize his combative nature. An example of this is the picture from 1894 in Friedrichsruh that Lenbach donated to the Museum of Fine Arts in Leipzig . From the mid-1890s, Lenbach finally created several versions that show Bismarck as the old man in Sachsenwalde , as a visionary former statesman without office who continues to take part in political events. An example of this type, from 1893, is exhibited in the Hessisches Landesmuseum in Darmstadt .

Lenbach made a pastel drawing of Bismarck on his deathbed.

"I am pleased to see myself immortalized by Lenbach's brush, as I would like to be preserved for posterity," said Bismarck during his visit to the Munich art exhibition in 1892. The connection between Lenbach and Bismarck was useful for both: Lenbach secured her reputation and economic success; respected personalities in society considered themselves to be painted by the Bismarck painter . For Bismarck, the portraits were a guarantee that his picture would be disseminated as he imagined it - with success, because reproductions of Lenbach's Bismarck portraits were widespread in bourgeois apartments. The effect continues to this day, because nowadays such reproductions illustrate history books, Bismarck biographies and the editions of his diaries. Even the first edition of the “people's edition” of his memoirs from 1905 showed one of these Lenbach portraits on the first page of the first volume.

The Villa Lenbach and the first marriage

In 1886 he acquired a plot of land in Munich, on the corner of Luisenstrasse and Brienner Strasse, in a close relationship opposite the Propylaea on Königsplatz . His Munich city villa, the Lenbachhaus , was built there in joint planning with Allotria member Gabriel von Seidl . The villa in the eclectic Italian Renaissance style , including the garden, is comparable to an Italian palazzo in terms of its dimensions and furnishings. However, the L-shaped floor plan is atypical for such a palazzo. Possibly he orientated himself in this point on the residence of Peter Paul Rubens in Antwerp , which he was able to visit in 1877. Lenbach also deviated from the original stylistic features of the Italian Renaissance in many other details.

On June 4, 1887, he married Countess Magdalena Moltke . In October 1888, the studio wing of Villa Lenbach was ready for occupancy. A comfortable apartment on the ground floor was planned for the couple, with the artist's workrooms above it. In 1890 the large, even more representative main building was finally completed. In spite of its classic appearance, the villa was equipped with the most modern technical comforts for the time. There were baths and steam heating. A power generator and special, day-bright studio lighting ensured that the artist could paint in the dark evenings.

Class and mass

Lenbach was heavily indebted for the construction and furnishing. The great need for money that he now had to cover with the income from his painting was not without consequences for his art. In the 1890s he created a veritable mass production. Working from photographs became the standard method. Lenbach used various tracing and copying methods for this purpose: he projected slides onto a screen and traced them by hand, or he wrote the projection with the help of a stylus. He traced photo enlargements on the painting surface. He used the so-called photopeinture , in which the projection was carried out on a light-sensitive, pre-prepared painting surface.

The use of photography as a tool was quite common and only condemned by a few critics. The majority of the public and the critics allowed the painters to use modern tools. Photography also suited Lenbach's eyesight, which declined with age. He preferred to work with the photographer Carl Hahn. In studio sessions he tried to create a relaxed atmosphere in which the model could present itself in an unconstrained manner. A number of photographs were taken during the session. He painted the actual portrait in the absence of the model. He often used not just a single photo from the meetings as a template; he often combined characteristic features from several photos into a portrait.

Lenbach's works of those years, however, often degenerated into quick painting. He often made little effort to hide the traces of the tracing. A few colored brushstrokes and highlights, that had to be enough to finish another picture of his hand.

In 1893 an embarrassing scandal broke out for Lenbach when a large-scale forgery affair was exposed. An employee had embezzled the painter's discarded sketches and drawings and passed them on to art dealers. These were the drawings of penniless art student colorize a little, partly wrong sign, and drove with these Lenbachs trade. In the 1895 trial, Lenbach was confronted with hundreds of these forgeries that covered the walls of the courtroom.

In general too, around 1890 criticism of Lenbach's conception of art increased. In 1887, the Swiss painter Karl Stauffer-Bern judged Lenbach: “... he is really an extraordinarily talented person who is lavishly endowed by nature, but who has managed to thoroughly mimic. Too much parlor frenzy and too little self-criticism from the man ... What has not been copied from nature ... and is related to cause and effect ... is virtuosity, not art in the true sense, and Lenbach's last works tend to be virtuoso. Since he has ... only to do with emperors, kings and popes, he has not had the time for serious work. "

When it mattered to him, however, he also created first-class portraits in those years. At the world exhibition in Chicago in 1893 , a major exhibition in Stockholm in 1897, at the Venice Biennials in 1897 and 1899, his pictures were highly valued contributions. Some of his portraits of Theodor Mommsen are also highly regarded , in which he concisely worked out the piercing gaze that is supposedly characteristic of the scholar.

Social prestige and social conflicts

In 1891 Lenbach was a member of the 75-member founding board of the Pan-German Association . In the summer of 1892 he arranged a glamorous reception for the dismissed Chancellor Bismarck in Munich - against the initial resistance of the Bavarian government, which feared entanglements with Prussia. He ordered a special train for Bismarck at his own expense, and from the balcony of the Lenbachvilla Bismarck received the homage of a crowd of enthusiastic Munich residents.

A few weeks after this event, a memorandum appeared in the Münchner Neuesten Nachrichten : Munich art had missed international developments and was out of date. The art market is based on Paris and not Munich. In the years before, from 1888, there had been disputes and public press feuds over the artistic direction. Commercial failures of exhibitions by Munich artists in the years from 1888 onwards caused bitterness and fueled the dispute. This culminated in the founding of the Munich Association of Visual Artists , which more than 100 artists joined, and the formation of the Munich Secession . Lenbach held against it: in 1893 he took over the presidium of the congress of the German Society for Rational Painting Methods in the Munich Glass Palace. There he gave demonstrations in painting technique in front of an audience and gave lectures in which he expressed himself disparagingly about the low level of art practice and understanding of art and the “irreverent conceit” of a “brazen art youth”.

He also played a key role that was prone to conflict in the dispute over the new building of the Bavarian National Museum . Until 1892, the Bavarian government had construction plans made without a public tender. The Munich Architects and Engineers Association then requested a public tender in a submission to the Ministry of Culture; Lenbach joined this demand. When the government did not respond to this, Lenbach publicly criticized the procedure in the press, demanding an increase in the building site and a more grandiose design that could stand alongside the buildings erected under Ludwig I and Maximilian II . So he was finally able to prevail. However, there was no public tender, instead the architects Gabriel von Seidl, Georg von Hauberrisser and Leonhard Romeis were invited to the competition.

Not least because of Lenbach's committed vote, the commission decided in favor of Seidl's draft after a controversial discussion. The foundation stone was laid in September 1894, and the inauguration was celebrated in September 1900.

Failure of the first marriage

The marriage with Magdalena was childless for a long time. In March 1888 the wife was given birth to a dead child. In January 1892, their daughter Marion was finally born. Lenbach was a proud and enthusiastic father; again and again he painted pictures of the pretty adolescent girl. However, the marriage, also for reasons of class, failed. Lenbach and his wife had completely different interests, she had nothing to do with painting, and in their free time they both had different relationships and pursued different occupations. In 1893 the wife suffered another miscarriage, and when the second daughter Erika was born in March 1895, Lenbach was plagued by the suspicion that the father was not he, but the previously trusted friend and family doctor Ernst Schweninger . In July 1896, Franz and Magdalena von Lenbach's marriage was divorced by amicable agreement. The daughter Marion stayed with her father, Erika came to live with her mother, who some time later actually married Ernst Schweninger.

The last few years

In October 1896 Lenbach married Charlotte (called Lolo) von Hornstein , born in 1861 , daughter of the composer Robert von Hornstein . Lenbach had already met her in her childhood as a frequent guest in her parents' house and later supported her as a mentor and proofreader when she was studying painting. The second marriage, this time of a common interest in art and mutual affection, went off harmoniously. His second wife took an active part in her husband's work and supported him with the arrangements for his portrait sessions and with his work on his gallery of famous contemporaries consisting of self-painted pictures . Their daughter Gabriele was born in 1899. The marriage of this daughter to Kurt Neven DuMont resulted in two daughters and two sons - the publishers Alfred Neven DuMont (1927–2015) and Reinhold Neven DuMont (* 1936).

In December 1896 Lenbach was elected President of the Munich Artists' Cooperative. In the years from 1897 onwards he tried other motifs, in particular painting people in nature, but without directly connecting with his early years. All the years before he had mostly portrayed men - now he painted almost exclusively portraits of women and occasionally nudes. He also gave up the harsh rejection of his own early work and allowed a portfolio of early works by him to be published in 1899. His style of painting also changed. Instead of the brownish gallery tones that were characteristic of his portraits for many years, he used lighter colors, the application of paint became thinner and less opaque, and sometimes he even used pure colors. His brush application became easier and quicker; he now preferred the alla prima painting instead of the glaze technique .

In 1897 Lenbach paid a visit to his home town of Schrobenhausen for the first time in 35 years. In 1898 Schrobenhausen made him an honorary citizen after he had given the city a picture of the Prince Regent. He supported his hometown financially, ideally and through his relationships with the new construction of the town hall, completed in 1903, for which Gabriel von Seidl was hired as architect.

Around 1900 he designed collector's pictures for the Cologne chocolate producer Ludwig Stollwerck for a fee of 6,000 marks.

Shortly before his death, Lenbach made a number of similar self-portraits. One of these pictures that he gave to his daughter Gabriele Neven du Mont, b. Lenbach bequeathed it is privately owned.

In 1902 he received the Commander's Cross of the French Legion of Honor . In the same year, on October 12th, on his return from an excursion to Schrobenhausen, he suffered a stroke . In December 1902 his health deteriorated further. He died on May 6, 1904 in his Munich villa. At the funeral procession, the people of Munich lined the streets in dense rows; a large number of prominent mourners from the arts and politics gave speeches and laid wreaths. He was buried in the Westfriedhof in a grave of honor provided by the city, grave no.81 on the wall on the left .

Reception in posterity

Lenbach's esteem in his time continued for a few years after his death until a commemorative exhibition in 1905–1906. In the new building of the Schack'sche Galerie , built in 1909 , Lenbach's works came into the largest and most magnificent hall on the first floor. There were both his originals and copies of the old masters made in the 1860s. Interest in Lenbach ebbed, however, and artists preferred, who were ascribed more originality. In 1922, with the reorganization of the gallery under Ludwig Justi , Lenbach's pictures had to vacate the hall of honor in favor of Anselm Feuerbach . His large-format copies were taken into the depot; the majority of Lenbach's copies have not been shown in public exhibitions since then. Since the renovation, redesign and reopening of the Schack Collection , some of his copies have shared what is known as the "Copy Hall" with copies by August Wolf . Lenbach's own works are housed in a neighboring hall.

On his 100th birthday in 1936, his work was again brought into public interest as part of the art policy of National Socialism . In connection with an anniversary exhibition in Schrobenhausen, numerous publications appeared in newspapers and magazines.

It was not until the late 1960s that an academic review of the entire work began, beginning with two exhibitions by Josef Adolf Schmoll called Eisenwerth in 1969 and 1970. This was followed in 1972 by Sonja Mehl's dissertation, later married name of Baranow, and in 1973 by a monograph by Siegfried Wichmann . Sonja von Baranow processed the holdings in the museum catalogs of Schrobenhausen and the Lenbachhaus in Munich according to modern art-scientific criteria. In 1986 the two biographies of Sonja von Baranow and Winfried Ranke appeared.

Exhibitions

- In 1986, on the occasion of his 150th birthday, Schrobenhausen, the city of birth, organized a large exhibition in the rebuilt Waaghaus with works by the artist that are in the possession of the major museums in Munich, Schweinfurt, Hamburg and Weimar, but also in private collections. A book by Dieter Distl / Klaus Englert was also published, which was devoted to the “Schrobenhausen boy” and also contains an interesting reproduction of the correspondence with his sisters: Franz von Lenbach, published by Verlag Ludwig, Pfaffenhofen / Ilm

- In 2004, on the 100th anniversary of Franz von Lenbach's death, the Neue Pinakothek and the Schack'sche Galerie dedicated a large anniversary exhibition to him.

- 2014: Prince painter , together with pictures by Franz Xaver Winterhalter and Heinrich von Angeli : Schloss Fasanerie near Fulda.

- 2016: On the occasion of the 180th birthday of the “great son of the city” and honorary citizen Franz von Lenbach, the city of Schrobenhausen is holding a comprehensive exhibition in autumn that will deal with the importance of Lenbach in the 21st century.

Museums

Today the Städtische Galerie is located in his former city villa in the Lenbachhaus in the state capital of Munich. In addition to many paintings by Lenbach and other 19th century painters , it houses an important collection of paintings by the Blue Rider .

The Neue Pinakothek , the Schack Collection in Munich and the museum in the house where he was born in Schrobenhausen have other extensive collections of Lenbach pictures .

literature

- Sonja von Baranow (under the maiden name Sonja Mehl): Franz von Lenbach (1836–1904). Life and work. Dissertation, Munich 1972

- Sonja von Baranow: Lenbach, Franz. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 14, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-428-00195-8 , pp. 198-200 ( digitized version ).

- Sonja von Baranow: Franz von Lenbach. Life and work. DuMont, Cologne 1986, ISBN 3-7701-1827-8 .

- Reinhold Baumstark (Ed.): Lenbach. Sun images and portraits. Pinakothek / DuMont, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-8321-7409-5 .

- Dieter Distl, Klaus Englert (eds.), Reinhard Horn: Franz von Lenbach - Unknown and Unpublished. Ludwig, Pfaffenhofen 1986, ISBN 3-7787-2080-5 .

- Brigitte Gedon : Franz von Lenbach. The search for the mirror. Nymphenburger, Munich 1999, ISBN 978-3-485-00825-9 ; Revised New edition DuMont, Cologne 2011, ISBN 3-8321-9410-X .

- Winfried Ranke: Franz von Lenbach. The Munich painter prince. Kiepenheuer & Witsch, Cologne 1986, ISBN 3-462-01783-7 .

- Lenbach, Franz von . In: Hans Vollmer (Hrsg.): General lexicon of fine artists from antiquity to the present . Founded by Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker . tape 23 : Leitenstorfer – Mander . EA Seemann, Leipzig 1929, p. 43-44 .

- Siegfried Wichmann : Franz von Lenbach and his time. DuMont, Cologne 1973.

- Wilhelm Wyl: Franz von Lenbach. Conversations and memories. Stuttgart and Leipzig 1904.

Web links

- Literature by and about Franz von Lenbach in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by Franz von Lenbach at Zeno.org .

- Lenbachhaus

- Lenbach Museum

- Video at ARD-Alpha, 16 min. (Online until April 20, 2022) Stories of Great Spirits: Red Carpet for Art Franz von Lenbach (1836–1904 / painter), Paul Heyse (1830–1914 / writer and Nobel Prize winner for literature) and Sophie Menter (1846–1918 / pianist) discuss on a stage in the old southern cemetery.

References and comments

- ^ Ranke: Franz von Lenbach. Pp. 9 and 10. In general, this article is based on Ranke's monograph, unless other sources are expressly stated.

- ^ The painters Franz von Stuck and Friedrich August von Kaulbach are also referred to as "painter princes". This should not lead one to lump these very different artistic personalities together.

- ↑ ahnen.ubuecher.de: Franz Joseph Lenbach + Josepha Herke ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ online-ofb.de Josepha Herke .

- ↑ For this section cf. the very detailed account of Lenbach's early biography in Ranke: Franz von Lenbach. Pp. 13-56.

- ↑ For this section cf. z. B. Ranke: Franz von Lenbach. Pp. 69-78.

- ↑ Examples see in Ranke: Franz von Lenbach. P. 35.

- ^ Baranow: Franz von Lenbach. Pp. 90-91.

- ^ Baranow: Franz von Lenbach. Pp. 92-93.

- ^ Ranke: Franz von Lenbach. P. 94.

- ^ Herbert W. Rott: Old Masters. Lenbach's copies for Adolf Friedrich von Schack. In: Baumstark (Ed.): Lenbach. Pp. 55-76.

- ↑ the authorship of the latter was long disputed, in Lenbach's time it was not attributed to Titian but to Giorgione (Herbert W. Rott: Alte Meister.Lenbach's copies for Adolf Friedrich von Schack. In: Baumstark, p. 62).

- ↑ cf. Rott: Old masters. Lenbach's copies for Adolf Friedrich von Schack. In Baumstark (ed.): Lenbach. Pp. 65-67.

- ^ Wilhelm Wyl: Franz von Lenbach. Conversations and memories.

- ↑ a b Lenbach in a letter to his sisters, 1876, according to Ranke, p. 145.

- ↑ on Lenbach's portraits of rulers see Jürgen Wurst: Lenbach and the ruler portrait. In: Baumstark (Ed.): Lenbach. Pp. 121-148.

- ^ Ranke: Franz von Lenbach. P. 243.

- ↑ a b Ranke: Franz von Lenbach. P. 247.

- ↑ A detailed description of the diverse relationships between Lenbach and other personalities of contemporary cultural life can be found in von Baranow: Franz von Lenbach. Pp. 24-33.

- ^ Von Baranow: Franz von Lenbach. P. 132.

- ^ Von Baranow: Franz von Lenbach. Pp. 130-131.

- ^ Jürgen Wurst: Lenbach and the portrait of the ruler. In: Baumstark (Ed.): Lenbach. Pp. 131-134 and p. 141.

- ↑ The presentation in this section follows Alice Laura-Arnold: Lenbach's Bismarck portraits and replicas. In: Baumstark (Ed.): Lenbach. Pp. 149-168.

- ^ The drawing is owned by the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus , Munich.

- ↑ Munich Latest News, June 27, 1892, p. 4.

- ^ Otto Fürst von Bismarck: Thoughts and memories. Volks-Ausgabe, first volume , JG Cotta'sche Buchhandlung Nach shorter, Stuttgart and Berlin 1905. (Fig. P. 1: F. v. Lenbach pinx (it). ) → Illustration in the book .

- ↑ The current three-wing floor plan was not created until 1929, when the architect Hans Grässel built the north wing opposite the studio on behalf of the City of Munich. Helmut Friedel: Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus and Kunstbau Munich. Munich 1995: Prestel, ISBN 978-3-7913-1466-2 .

- ↑ Von Baranow: Franz von Lenbach. P. 63.

- ↑ Quoting from Ranke, p. 328.

- ↑ Michael Peters: " Alldeutscher Verband (ADV), 1891-1939 ", in: Historisches Lexikon Bayerns .

- ^ Ranke: Franz von Lenbach. P. 295.

- ↑ Detlef Lorenz: Reklamekunst um 1900. Artist lexicon for collecting pictures , Reimer-Verlag, 2000, ISBN 978-3-496-01220-7 .

- ↑ On this section cf. von Baranow: Franz von Lenbach. P. 6.

- ↑ Rott: Old Masters. Lenbach's copies for Adolf Friedrich von Schack. in Baumstark (Ed.): Lenbach. P. 69.

- ↑ Tour of the Schack Collection. In: pinakothek.de. Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, accessed on February 12, 2020 (upper floors, halls 11 and 12).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Lenbach, Franz von |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Lenbach, Franz Seraph Ritter von (full name); Lenbach, Franz Seraph |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German painter |

| DATE OF BIRTH | December 13, 1836 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Schrobenhausen |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 6, 1904 |

| Place of death | Munich |