Bad Kissingen

| coat of arms | Germany map | |

|---|---|---|

|

Coordinates: 50 ° 12 ' N , 10 ° 5' E |

|

| Basic data | ||

| State : | Bavaria | |

| Administrative region : | Lower Franconia | |

| County : | Bad Kissingen | |

| Height : | 206 m above sea level NHN | |

| Area : | 69.93 km 2 | |

| Residents: | 22,443 (Dec. 31, 2019) | |

| Population density : | 321 inhabitants per km 2 | |

| Postal code : | 97688 | |

| Primaries : | 0971, 09736 | |

| License plate : | KG, BRK, HAB | |

| Community key : | 09 6 72 114 | |

| LOCODE : | DE BKI | |

| City structure: | 9 districts | |

City administration address : |

Rathausplatz 1 97688 Bad Kissingen |

|

| Website : | ||

| Lord Mayor : | Dirk Vogel ( SPD ) | |

| Location of the city of Bad Kissingen in the Bad Kissingen district | ||

Bad Kissingen (before April 24, 1883 Kissingen ) is a large district town in the district of the same name and the seat of the district administration. The Bavarian State Bath is the fourth largest city in the Lower Franconian administrative district and has been a joint regional center with Bad Neustadt since 2016 . Bad Kissingen is the location of the Bavarian state authorities and, in its central location, is a popular conference and event location. The spa town lies in the valley of the Franconian Saale , on the south-eastern edge of the Rhön . A wide range of indications is treated as a mineral and mud spa .

Since the 18th century, Kissingen was developed into a world bath in competition with Karlsbad and Baden-Baden . It has the oldest spa garden (1738) and the largest ensemble of historical spa buildings in Europe, which was built under the aegis of the two Bavarian rulers Ludwig I (1825–48) and Prince Regent Luitpold (1886–1912). In addition, the spa town is the oldest graduation site in Europe and the second most visited spa in Germany, after Bad Füssing .

According to a representative Emnid survey is Bad Kissingen well tester spa town in Germany , also one of eleven traditional European spa towns, in addition to Baden-Baden, Karlovy Vary, Spa , Vichy , Bath and other than Great Spas of Europe (English: Famous spa resorts in Europe ) an entry aspire to be a UNESCO World Heritage Site .

geography

location

Bad Kissingen is centrally located in Germany, in the Main-Rhön region . The spa town is easily accessible by car, with junctions on the 7 and 71 autobahns . Accessibility by train has also improved. Berlin can be reached from Schweinfurt main station (30 train connections per day from Bad Kissingen, from 22 minutes) in under three and a half hours, Munich from 2:33 hours and Hamburg from 3:57 hours, and Schweinfurt will also have a direct IC connection in 2028 . Despite being easily accessible, Bad Kissingen is in a quiet location.

Kissingen is the capital of the Bavarian spa region, with a total of five spas. These include the other two state spas, Bad Bocklet and Bad Brückenau, as well as Bad Neustadt and Bad Königshofen . Bad Kissingen has the classic low mountain range for central European spas. It is located on the southern edge of the German low mountain range , east of the Spessart and on the edge of the Rhön biosphere reserve , 20 km from Kreuzberg (928 m). 20 km east of the spa town are Ellertshäuser See and the Haßberge Nature Park . The international winter sports resort Oberhof in the Thuringian Forest can be reached in a good hour's drive .

Viticulture was once practiced on the mountain slopes around the town . The Franconian wine country begins south of the outskirts with the northernmost wine town of Franconia Wirmsthal .

City structure

Bad Kissingen is divided into the core city and eight other districts, which were created in 1972 as a result of the Bavarian regional reform through incorporations (population in brackets as of January 1, 2016):

|

|

|

Natural space

The large district town of Bad Kissingen largely belongs to the main unit South Rhön, the south-eastern remainder to the Wern-Lauer-Platte.

climate

The spa town is located on the border of Franconia and not far from the winter sports region of the Rhön. Due to the Saale, the Kissinger mixed forest and the relatively low location in the slipstream of the Rhön, the climate is low in precipitation, relatively mild in winter and warm in summer.

Salt pans, healing springs and spa districts

Mineral and salt deposits from the Zechstein Sea form the basis for the mineral springs in the South Rhön and their medicinal baths . Originally only used for salt production, they have also been used for therapeutic purposes at least since the early modern period .

From the Kissinger spa district to the north, along the Franconian Saale salines and healing fountains, over the district of Hausen to the spa suburb of Bad Bocklet for 8 km. After the Kissinger spa district in Hausen, the Lower Saline , which was 1200 years old, followed with a graduation tower , and then the Upper Saline (Royal Saline) from 1763. In historical times, graduation works for salt production stretched almost 2 km here. Then follows in the Kleinbracher Saaleschleife the former small monastery Brachau ( St. Dionysius , documented 823) which was probably also involved in salt extraction (see picture: Middle Ages ). Finally, at the current city limits of Bad Kissingen, but already in the Bad Bockleter area, two more healing wells form the end of the healing spring area, which is functionally part of Kissingen.

The historic spa district was created at the mineral springs located immediately southwest of the Kissingen old town. It consists of four large Belle Epoque complexes . Three of them are located on the eastern bank of the Saale around the spa garden: Regentenbau , Arcadenbau and Wandelhalle , with a fountain hall in the west wing. All buildings are connected to one another. According to the motto of the builders, that you should plan a spa district for bad weather, because it works anyway when the weather is nice and the arcades also offer protection from the heat. A spa of unprecedented size was built within 79 years . A tour through all the permanently open and accessible arcades, halls, reading and gaming rooms, the sophisticated Kurgartencafe, walking hall and fountain hall covers one kilometer.

In addition, on the other (western) bank of the Saale is the huge complex of the former Luitpoldbad , with the Luipold Casino .

See also: Kurbauten

- Historic spa district

Regentenbau

with Ludwigstrasse

Healing fountain

Functionally, seven medicinal springs belong to the spa town today , all of which are in the Saale valley. The first three mentioned below are the classic sources at the spa garden. The next two are to be found further north, in Hausen, which was incorporated in 1972. After all, Luitpolsprudel “old” and “new” are located in the far north, right on today's city limits. This runs here in the middle of the Saale, but the sources are on the bank belonging to Bad Bocklet, on the Großenbracher district.

- The Rakoczy fountain in the foyer is best known and has become a synonym for the spa town ( Rakoczi festival , Rakoczy horse show) . The spring was discovered in 1737 when the halls were relocated and named after the Hungarian national hero Ferenc II. Rákóczi, who was popular at the time . From the iron-containing sodium chloride - Säuerling ( mineral drinking water ) is the addition of magnesium sulfate and sodium sulfate, and the Kissinger bittern prepared. The rakoczy water tapping points are in the fountain hall, the closed arcades to the north and in the foyer at the entrance to Kurhausstrasse . The tapping point for the Kissinger bitter water is in the fountain hall.

- The Maxbrunnen (also: Sauerbrunnen ) in the well temple in the spa garden is the oldest Kissingen healing well and was first mentioned in 1520. The fountain has been named after it was revised under King Max I Joseph of Bavaria in 1815. The sodium chloride acid (drinking cure) has extraction points at the Max Temple in the spa garden and in the fountain hall.

- The Pandur fountain (previously also: Scharfe Brunnen , Badbrunnen ) in the lobby has been known as the spa fountain since 1616. It got its current name in the 18th century after the infamous Pandur Corps, which was a topic of conversation among spa guests. The iron-containing sodium chloride sourling (drinking cure) has the same extraction points as the rakoczy fountain.

- The round fountain is located at the graduation tower. The little-known fountain under a glass dome is the most interesting and can be observed. It intermittently , so from time to time it surges violently and then sinks again. The brine spring was discovered in 1788, developed for salt extraction and has also been used therapeutically since 1841. It is an iron-containing sodium chloride acid ( spa treatment , inhalation ).

- The Schönborn-Sprudel is located in what is now the Hausen district, on the main street, by the Hausen monastery . The thermal spring (spa treatment) was developed for salt production in 1764 and only used therapeutically a good 100 years later. Its name goes back to the Würzburg prince-bishop Johann Philipp von Schönborn . Today with the Schönbornsprudel u. a. KissSalis Therme and the Hotel Kaiserhof Victoria .

- The Luitpoldsprudel "old" on the Saale loop north of what is now the Hausen district was drilled in 1908 and made accessible to the spa in 1913. His name pays tribute to Prince Regent Luitpold II of Bavaria, who had just passed away . The iron-containing sodium-calcium-chloride- hydrogen carbonate - sulphate- acid (drinking cure) has extraction points in the fountain hall, in the foyer at the entrance to Kurhausstraße and the open vestibule and from April to October directly on site.

- The Luitpoldsprudel "new" in the same place was found in 1986 in the course of the new development to preserve the "old" Luitpoldsprudel. It is an iron-containing sodium-calcium-chloride-hydrogen carbonate-sulphate acid (spa treatment).

Surrounding mountains

The spa town is surrounded by seven more striking mountains. The closest is the Altenberg and borders directly on the spa district, while the Scheinberg is the farthest at 4 km. The Franconian Saale flows precisely from the north into the city and out again in the south-west between Scheinberg and Altenberg.

| Staffelsberg | Sinnberg | |

|

Osterberg | |

| Altenberg |

Finsterberg Scheinberg |

Station mountain |

- The Altenberg (formerly: mons antiquus ; height: 282 m) is a circular mountain around which the Saale once ran to the west, via today's Marbach and Westring to the south bridge. On the mountain there is a prehistoric ring wall , probably from a Celtic refugee castle . Furthermore, the weather shelters Walhalla (garden temple), round temple and sun salette . During her spa stays, the Empress Elisabeth of Austria-Hungary , known as Sisi , liked to go for a walk here; In her honor, the Empress Elisabeth Monument was erected there in 1907 .

- The Staffelsberg (short form: Staffels ; height: 382 m) got its name from the former, rectangular vineyards with a staggered edge (see right picture). On the mountain there is the Ludwigsturm , with an antenna from the Schweinfurt radio station Radio Primaton (90.5 MHz), a training center for the St. George scouts and the cafe and restaurant Jagdhaus Messerschmitt .

- The name of the Sinnberg (height: 370 m) possibly comes from Asin Syn . On it are the Bismarck Tower , Cafe Sinnberg and a Madonna sculpture on the slope . From 1928 to 1965 there was a ski jumping hill on the mountain.

- The Osterberg (height: 375 m) in the district of Winkels indicates its location east of the city by name. Its northern part was formerly called Schleglsberg . The Friedenskapelle lies on the north slope .

- The Stationsberg (height: 351 m) is located in front of the somewhat more inferior, but neither known nor incisive Winterleite (height: 356 m). The Kissinger Kreuzweg , created around 1895, leads to the Stationsberg from the north . An older way of the cross began at the foot of the mountain, at today's Kurtheater , and led along today's Von-der-Tann-Strasse . It was sold to Poppenroth in 1892 . At the northern end of the Stationsberg there is a cemetery of honor and a memorial on the occasion of the German War and the Degenberg Clinic in the south . The Botenlauben castle ruins are located on a small knoll at the southern end of the mountain .

- The Finsterberg (height: 328 m) in the Reiterswiesen district also indicates its location by name, with its shady northern slope towards the old town. On top of it was a ski jumping hill that collapsed in a storm in 1968 and was then torn down, and the Ballinghain , which was created by the spa doctor Franz Anton von Balling , of which remains are still present. The terrace swimming pool , built in 1954, is located on the western slope .

- On the Scheinberg (height: 401 m) in the Arnshausen district stands the Wittelsbach Tower , which was built to compete with the Bismarck Tower on the Sinnberg, and a mountain inn with a private brewery. On a hill to the north of it lies the Eiringsburg , a castle stables from the 9th century .

See also: Parks and Natural Monuments

Surname

etymology

The origin of the place name Kissingen is almost unclear in historical research. The affiliation suffix "-ing", which denotes the dependence of a settlement on a liege lord or the like, is secondary in this place name. A consistent spelling with the ending can only be found from the 18th century. Possibly the first part of the name consists of the Celtic personal name "Citus", which was derived from the Celtic suffix "acum".

Earlier spellings

Earlier spellings of the place from various historical maps and documents:

|

|

history

Beginnings

In prehistoric times, the Bad Kissingen area, in contrast to the neighboring area around Schweinfurt to the south , was only populated to a very limited extent. The location of a Neolithic settlement in the Steingraben corridor in the north of Bad Kissingen is now built on. In addition, there were only a few finds such as flint tools in today's districts of Arnshausen and Garitz, as well as a stone hatchet and a stone ax.

Kissingen was first mentioned in a document on June 21, 801 as a chizzicha in a deed of donation that has since disappeared, in which a nobleman named Hunger assigned his property in Kissingen to the Fulda monastery . In the 9th century the abbot Rabanus Maurus made a copy of the document in a cartular . This copy has also been lost (since the Thirty Years' War ), but the contents of the cartular have been preserved because the monk Eberhardus of the Fulda Monastery included it in his Codex Eberhardi .

middle Ages

In the Middle Ages , Kissingen was still an insignificant place, smaller than the two neighboring cities of Münnerstadt and Hammelburg . The development to the authority town of the surrounding small towns started late (see: Bavarian Kingdom ).

For the period between the 10th and 12th centuries , little source material has survived relating to Kissingen. It is certain that the Fulda monastery lost power in favor of the margraves through a donation of church property to the vassal Rudolf, an ancestor of the margraves of Schweinfurt , initiated by King Otto I. later this should pass to the Henneberg family . In 1057 Judith, a daughter of Margrave Otto , the last Margrave of Schweinfurt, married Count Boto of Carinthia. Through this marriage, various properties in and around Kissingen went to Boto. When he died with no descendants, his sister-in-law Gisela (Judith's sister) inherited his property. After her death, this went to the Andechs-Meranier family , to whom the Henneberger Poppo VI. married Sophia came from Istria. Their son Otto von Botenlauben later lived with his wife Beatrix von Courtenay in Botenlauben Castle, which was first guaranteed for 1206 in what is now the Reiterswiesen district ; its name goes back in all probability to Boto von Carinthia. According to a theory by Reinhard von Bibra, the name may also come from a landowner named Boto, who owned the Botenlauben estate below the castle (which later became the hamlet of Unterbodenlauben , which grew together with Reiterswiesen) and who gave it to the Fulda monastery in 797 . This estate would have been created before the castle and would have been the inspiration for its name when it was built.

The Eiringsburg , located south of today's golf course , can be identified in 822 . The owner of the castle, called Iring , issued a deed of donation in which it went to the Fulda monastery. In 823, the small monastery Brachau , located in the Kleinbracher Saaleschleife, was first attested, today known as St. Dionysius monastery . The Bremersdorf settlement, which was first authenticated for 1122, was near the Klaushof wildlife park . As early as 1394, the settlement was no longer mentioned in the Auraer Central Order , as it was probably already deserted. In addition to the ground plan of a church, traces of agricultural use can still be found in the deserted area of Bremersdorf.

Despite the sale of the messenger arbor by Otto von Botenlauben to the Würzburg bishop Hermann I von Lobdeburg , Kissingen remained in the possession of the Hennebergers, which was now affected by the disputes between them and the Würzburg clergy. During this time, Kissingen was first mentioned in a document in 1279 as an oppidum ( city ), then in 1293 as castrum cum oppido (camp with a city) , and most recently in 1317 as a stat . The city charter was finally Kissingen 1296 by the later Emperor Louis IV. Of Bavaria and was in 1396 by the Bishop of Wurzburg Gerhard von Schwarzenburg confirmed. In 1309 and 1319 the conflict between the Hennebergers and the church made reconstruction clauses necessary for Kissingen; the cityscape that was created in 1319 did not change for the next few centuries. In 1394 Duke Swantibor III sold. from Pomerania Kissingen to the Würzburg monastery , whose wife Anna had inherited Kissingen from her parents in 1374.

In the 15th and 16th centuries , a regular city life developed in Kissingen in administration with the official cellar as the representative of the bishop, in trade with the development of fairs and in the judiciary with the exercise of judicial rights, whereby in difficult cases the city court of Münnerstadt as Example served.

Early modern age

In the course of the Peasants' War of 1525 , many angry peasants also gathered in Kissingen and received support from the Kissingen pastor Johannes Wüst. Her anger was directed against Prince-Bishop Konrad II von Thüngen , who had to flee to Heidelberg at times . The Hausen Monastery , the Aura Monastery , the Frauenroth Monastery and the Aschach Castle were devastated ; the messenger arbor became a ruin. The uprising was put down when Konrad II carried out a criminal court in the bishopric, in the course of which Pastor Johannes Wüst was beheaded.

Kissingen was best known for its medicinal springs, which were already proven in 823 . The first verifiable spa guest was recorded as early as 1520, and in the same century the reputation as a health resort was strengthened. The played salt production in Hausen an important role. The negotiations between Prince-Bishop Friedrich von Wirsberg in 1559 about the salt boilers there with Kaspar Seiler from Augsburg and Berthold Holzschuhmacher from Nuremberg as tenants failed. In contrast, the negotiations between Prince-Bishop Julius Echter von Mespelbrunn in 1576 with the Münnerstadt citizen Jobst Deichmann had long-term success. In the same year, Echter issued new city regulations. As one of several prominent spa guests, Count Georg Ernst from Henneberg visited the city several times between 1573 and 1581 .

In the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), the Swedish King Gustav II Adolf came to the neighboring, Protestant imperial city of Schweinfurt in 1632 , where the General Field Marshal of the Swedish Army Karl Gustav Wrangel set up his headquarters. After three years of interim Swedish government over the Würzburg monastery , the situation was temporarily defused by the return of Prince-Bishop Franz von Hatzfeld in 1634. Nevertheless, the Swedes stood in front of Kissingen in 1636 and could only be dissuaded from the destruction of the city by paying a ransom of 3,000 Reichstalers . The legend of another successful defense against a Swedish attack in 1643 in the Kissinger bee battle has not been historically proven.

In 1611 a third of the Kissingen population fell victim to the plague with 284 deaths, and the Thirty Years' War claimed more. A directory of the whole citizenship from 1650 only contains 110 names. Then the population recovered to 152 citizens in 1682. The handicrafts in the city were promoted by the guild regulations issued by the prince-bishop . The Kissing bakery trade, for example, flourished to such an extent that bakers from neighboring Neustadt an der Saale saw their trade threatened. In addition, the Kissingen economy was supported by the increasing number of spa operations.

Ascent to the world bath

Friedrich Karl von Schönborn-Buchheim , Prince-Bishop of Würzburg and Bamberg (1729–1746) “ wanted to create a health resort that could be compared to Karlsbad. “Kissingen should have a place in the game of the great world pools. In 1737 the sovereign commissioned his master builder Balthasar Neumann , who fortunately was also a town planner, to relocate the Franconian Saale to the southwest. The east bank was dangerously close to the Pandur fountain . In the course of the construction work, the Rakoczi spring in the old river bed was (re) discovered, exposed and captured. The pharmacist, city councilor and temporary mayor of Kissingen, Georg Anton Boxberger, was a co-discoverer of the spring, analyzed the chemical composition and recognized the healing power of water. The Boxberger-Neumann monument in the rose garden commemorates this collaboration, which was crucial for the further development of the spa.

The space gained by relocating the Saale away from the city was to be used as a central spa area and was raised by two meters to protect against flooding and surrounded by retaining walls (see picture: Kurbauten ). This major and key project, completed in 1738, enabled the subsequent extensive spa buildings and the development of Kissingen into an international bathroom.

Bavarian Kingdom

Bad Kissingen is structurally shaped by the Kingdom of Bavaria like hardly any other city. The spa town owes its rise from the province to a global spa, which eventually gained importance throughout Europe, solely to the location in Bavaria and the foresight of its rulers, with the talent for visionary urban planning , especially of Ludwig I of Bavaria .

At the beginning of the 19th century , as a result of the Napoleonic Wars, the Kissingen spa system experienced a setback. In 1806 the reign of Ferdinand III began. Archduke of Austria-Tuscany over the Grand Duchy of Würzburg , to which Kissingen belonged. As part of Ferdinand's efforts to stimulate an upswing in the Kissingen region, the Horch medical council prepared an expert report in which Kissingen turned out to be a provincial spa that could not meet the requirements of the spa at the time. The situation did not improve until 1814 with the integration of Franconia into the Bavarian kingdom and the investments made possible by the Wittelsbach family .

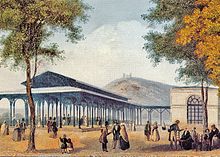

In 1824 the brothers Peter and Ferdinand Bolzano became tenants of the spa. In the 19th century , Kissingen became a fashionable seaside resort and was expanded during the reign of Ludwig I. The number of spa guests multiplied from 173 in 1814 to 2,200 in 1836. The famous Bavarian court architect Friedrich von Gärtner built the arcade building from 1834 to 1838, which is still characteristic today . In 1839 a new jug magazine was created , from which clay jugs with Kissinger healing water were sent all over the world. The softening of the city made it possible to expand into a spa town around today's Ludwigstrasse .

During the Main Campaign as part of the German War , on July 10, 1866, in the battle of Kissingen, there was a dogged battle between Bavarian and Prussian troops , also in the middle of the spa district. Numerous graves and monuments commemorate the battle. In battle, the Bavarian army was weakened by major logistical deficiencies. The Kissingen business people were successful when they made King Ludwig II aware of the need for a train station for Kissingen. In 1871 the railway line between Schweinfurt and Kissingen was opened.

Reich Chancellor Prince Otto von Bismarck , who came to Kissingen several times for a cure, barely escaped an attack here in 1874 , perpetrated by Böttcher journeyman Eduard Kullmann in today's Bismarckstrasse 16 . The motif was Bismarck's fight against the Catholic Church in the Kulturkampf (see: Well-known spa guests in Bad Kissingen ). In 1883 the city magistrate and the curcommission applied to the Kissingen district office to raise Kissingen to the bathroom , so that “the main meaning of Kissingen would appear appropriately” and to avoid the confusion of names with the places Kitzingen in Franconia and Vlissingen in the Netherlands . King Ludwig II complied with this request on April 24, 1883. From 1890 Bad Kissingen was the first town in Bavaria to have all its houses connected to the sewer system. The Kissinger example was groundbreaking for Bavaria. In 1907 the number of spa guests rose to 28,000, with only 5,000 residents. 1908 Bad Kissingen circle immediate (county-level) city. In 1909 there was a flood of the century . Between 1910 and 1913, the Munich architect Max Littmann built , building on the architecture of Friedrich von Gärtner, the foyer and the Regentenbau .

Weimar Republic

The First World War ended the Belle Epoque suddenly . With the decline of the Kingdom of Bavaria , the German Empire , the Habsburg Monarchy and the Russian Empire , with the German and Russian revolution , communism and new republics.

This led to a social turning point with far-reaching consequences for international spas like Kissingen. The heyday of the nobility and the bourgeoisie, and thus the typical guests who had previously shaped spa life, was over. Since then, Bad Kissingen has been a former world bath. The English also stayed away, but the Schweinfurt English came , as the Kissing people dubbed the Schweinfurt day tourists. Thanks to advances in technology, long-distance travel became more convenient for the upper class and classic Central European destinations became less important. All these developments led now and in the following decades to the closure of luxury hotels; This is also the case in Bad Kissingen, for example from Kaiserhof Victoria , Grand Hotel ( Haus Collard ), Fürstenhof , Hotel Krosse , Café Messerschmitt (hotel) or Ballinghaus . While elsewhere, such as For example, in Wiesbaden , where grand hotels were converted into apartments or in Switzerland some of them are still vacant and are in disrepair, many closed Kissinger (spa) hotels retained their hotel-like character through later use by social insurance companies or by private health resorts and sanatoriums . Several houses have since been (partially) converted back into hotels, such as Kaiserhof Victoria, Bristol or Dappers Hotel (see: Present ).

After the First World War there were even more spa guests than before, but different ones; from a new social middle class such as politicians, bankers, civil servants, senior employees and privateers . As a result, the number of spa guests rose to a new high of 36,486 in 1922.

With the end of the German Empire and the Bavarian monarchy, the Bad Kissingen magistrate constitution was replaced by a city council in 1919; the mayor has held the title of mayor since 1928 . Since the administration of the growing city needed more space, the New Town Hall was opened in 1929 in the Heussleinschen Hof . The old town hall is used today as a community center.

National Socialism

During the National Socialist era , many foreign spa guests stayed away from the city. In order to give the economy new impetus, Lord Mayor Max Pollwein tried to settle military in the city. In 1937, after a year of construction, the 8.2 hectare Manteuffel barracks , named after Field Marshal Edwin Freiherr von Manteuffel , was opened. On April 1, 1940, Bad Kissingen lost its district immediacy , but regained it on April 1, 1948.

After the Catholic Pallottinerpater Franz Reinisch in the Manteuffel-Kaserne the oath of allegiance to Hitler refused, he was in 1942 in Brandenburg prison-Gorden in an der Havel Brandenburg murdered. This is indicated by a memorial stone on Pater-Reinisch-Weg on the former barracks site.

During the Second World War , Germany's most violent aerial battles broke out over neighboring Schweinfurt due to the rolling bearing industry , a key industry that is important for the war effort . The Swedish ball bearing factories therefore relocated parts of the administration from the local plant to Bad Kissingen. For the same reason, the telecommunications office was relocated from Schweinfurt to the spa town (where it remained until it was dissolved in 1995), as indicated by Bad Kissingen's shorter phone code (0971) compared to Schweinfurt's (09721) to this day.

During the war, many of the war wounded were cared for in Bad Kissingen, mainly from Schweinfurt. In 1945 there were 3,000 wounded in 30 hospitals . Since Bad Kissingen was not declared a hospital town, which would have precluded direct war measures under the Geneva Conventions , Colonel Karl Kreutzberg, with the support of General Hans von Obstfelder , initiated the surrender of Bad Kissingen without a fight, which took place on April 7, 1945. The city was spared major war damage; contemporary witnesses only report a few bombs that fell near the slaughterhouse . The greatest war damage was the partial demolition of the Ludwigsbrücke , which was rebuilt after the end of the war, a few hours before the handover.

post war period

After the Second World War, Bad Kissingen was subordinated to the American military government under Captain Merle A. Potter following a constituent meeting on July 17, 1945 . The Manteuffel Barracks was renamed Daley Barracks , where US Army soldiers were stationed. The American nickname for Bad Kissingen was analogous to LA (for Los Angeles ) BK (pronounced: bikey ).

In 1946, during the talks about the future structure of Germany, which ultimately led to the formation of the bizone , Bad Kissingen was also discussed as a meeting place for the cross-zonal state council, but was ultimately not given a chance.

On January 27, 1947, the first free local elections were held. From this, the CSU emerged victorious with 12 seats in the Bad Kissingen city council; In 1952, she appointed Hans Weiß , the city's mayor for decades, who shaped the entire post-war period.

The Americans withdrew from the spa zone in order to enable the spa operations to start again (among other things, the lobby was used to store and repair war equipment). With the structural help of US soldiers, what was by far the most modern terrace swimming pool at the time was opened on Finsterberg in 1954 , as a park with over 10,000 roses. In the opening year, the 66th German Swimming Championships took place with more than 1,000 athletes. Many expellees also came to Bad Kissingen, which is why special construction programs began in 1950. Business start-ups by displaced persons created numerous jobs.

The spa guest profile had shifted (see: Weimar Republic ). The social insurance agencies set up health clinics, and the guests who had been admitted were now called social guests . Baden-Baden , on the other hand, did not allow any social security houses and was now overtaking Bad Kissingen, which slipped into provinciality and lost part of its upper class clientele. However, the social insurances brought the advantage of the year-round spa operation, while in the 1950s the spa district was still deserted in winter, with the iron blinds on the shops down. The large new buildings of the social insurance did not shape the cityscape, but kept in the background, as the spa district was completely built up in historical times.

After the Bavarian King Ludwig I closed the Kissinger Spielbank, founded in 1830, in 1849, the Bavarian state opened the new casino in 1955, which was moved to its current location in 1968, the Luitpold Casino in the north wing of the Luitpoldbad . Club Twister , launched in 1961, served as a springboard for later well-known artists. Udo Lindenberg performed here several times a week in 1969 with his first band Free Orbit . The Almstedt luxury restaurant in Ludwigstrasse closed around 1965 and Kissingen lost its first restaurant .

Around 1970 there was a building boom that still shapes the image of the city periphery in several places. In addition to health clinics from social insurance companies , large (health) hotels, also in the luxury segment, have now again been built as a result of funding , but all in peripheral locations. The number of overnight stays finally exceeded the two-million mark. As in the time after the First World War, some large (spa) hotels were closed again, such as on Staffelsberg , and put to another use (while the trend reversed again in the 21st century , see: Present).

present

Since the complete withdrawal of the US facilities from Bad Kissingen, which last belonged to the US Army Garrison Schweinfurt in 1993, the Daley Barracks u. a. the municipal music school and a cinema. The health structure reform of 1996 brought drastic savings in social security cures , which led to greater job losses. The number of overnight stays fell from 1.9 million (1995) to 1.4 million (1997 and 1998) with 140,000 guest arrivals. With the KissSalis Therme , the spa town got a large spa area in 2004, the thermal water of which is fed from the Schönborn spring. The team from Ecuador stayed in the city for the 2006 World Cup . After a strong flood in 2003, a flood protection system was completed in the spa area in 2007. In 2011, the 6th Day of the Franks took place in Bad Kissingen under the motto Singing, Sounding Franconia . In 2012, Bad Kissingen was awarded the title Rose City by the Society of German Rose Friends .

Classic spas with a historical ambience have become more popular again with private guests, including younger people. Since the number of social guests had fallen sharply at the same time as a result of the health structure reform , several insurance companies and sanatoriums became ( wellness ) hotels. After the conversion of the formerly state spa administration and the communal bathing company into the privately-owned Bayerisches Staatsbad Bad Kissingen GmbH , it was therefore possible, as it did until the 1950s, to attract more private guests in the upscale segment again. In 2003 the new record was 1.55 million overnight stays with just under 190,000 guests. In 2008 there were 1.48 million overnight stays with 220,000 guests, with the general trend of increasing guest arrivals and shorter stays. In 2018 the spa town again had over 3,000 hotel beds and the number of hotels rose to 27.

additional

Well-known spa guests in Bad Kissingen

Crowned heads led the Kissingen guest lists, such as King Otto I of Greece , Emperor Franz Joseph I , Empress Elisabeth of Austria (also called Sisi ), Tsar Alexander II , King Ludwig I of Bavaria and the fairytale king Ludwig II of Bavaria .

Well-known politicians such as Chancellor Prince Otto von Bismarck , Theodor Heuss and Franz Josef Strauss also took cures in the Weltbad ; Writers such as Theodor Fontane and Leo Tolstoy ; Composers such as Gioachino Rossini and Richard Strauss ; Painters like Max Liebermann and Adolph Menzel ; Fashion designers like Heinz Oestergaard ; Architects like Walter Gropius ; Archaeologists like Heinrich Schliemann ; Inventors and business people such as Alfred Nobel , Graf Zeppelin and the American ketchup manufacturer Henry John Heinz .

Bismarck visited Kissingen several times for a cure. Here he wrote the Kissinger Dictation in 1877 , in which he outlined his foreign policy concept. During his first stay at the spa in 1874, he barely escaped an attack on what is now Bismarckstrasse , perpetrated by the journeyman cooper Eduard Kullmann . The motif was Bismarck's fight against the Catholic Church in the Kulturkampf . Nevertheless, between 1876 and 1893, Bismarck came to Bad Kissingen for a cure 14 times. During these spa stays, however, he lived in the Upper Saline in today's Hausen district . The building now houses the Obere Saline Museum with the Bismarck Museum department . In 1885, on the occasion of his 70th birthday, Bismarck became an honorary citizen of Bad Kissingen (see: Otto von Bismarck as an honorary citizen ).

During the second Moroccan crisis in 1911, the head of the Foreign Office, Alfred von Kiderlen-Waechter, received the French ambassador Jules Cambon for a political discussion. In 1912 Kissingen was again the scene of talks between Kiderlen-Waechter and Jules Cambon and the ambassadors of Italy and Austria-Hungary.

Federal President Heinrich Lübke came to the spa town ten times. During his spa stay in 1966, he and his wife Wilhelmine Lübke received the Thai royal couple Bhumibol Adulyadej and Sirikit here . During his stay at the spa in 1964, he met Herbert Wehner (SPD) in Bad Kissingen , where both of them agreed on Lübke's re-election as Federal President and in favor of a grand coalition.

Richard Strauss tried in vain the Kissinger Kurorchester to get them, even Mozart and Schubert to play. Heinz last took a cure in Bad Kissingen in 1914, when he was surprised by the First World War and was no longer allowed to leave the hotel. Nevertheless he managed to escape via Holland and return to the USA. This was his last visit to Germany. The founder of the Bauhaus Walter Gropius took a cure in Bad Kissingen in the year the Bauhaus was founded in 1919.

Development of the Kurviertel since 1945

With the exception of a few bombs at the slaughterhouse, the spa town survived the war completely unscathed. The entire ambience of the Belle Epoque , the heyday of the spa, was preserved in the spa district until the end of the 1950s . With the social guests , kitsch and mass operations then found their way into shops and restaurants, with concentration on the Balthasar-Neumann-Promenade at the Rosengarten, the so-called bazaar . While the upscale fashion shops and jewelers typical of luxury spas continued to dominate the spa garden.

In the 1960s and 1970s, historical ambience in public spaces and in private houses, as in many places in West Germany, was often removed, purified or modernized. The spa district and old town had lost their charm due to countless pinpricks and style breaks. From the 1990s on, there was a rethink. So were u. a. the two modern fountains in front of the arcade building and the street lamps in Ludwigstrasse were replaced in their original form. The renovation of the lobby and the Regentenbau were completed in 2000 and 2005, respectively. The spa district, with the exception of the bazaar , shone again in its old splendor and the former world spa continued for five years almost unbroken to the charm of bygone days. Until the Steigenberger Kurhaushotel is closed and demolished (see: Steigenberger Kurhaushotel ). The changes in retail did not pass the spa town by either, with owner-operated shops being replaced by branches .

Steigenberger Kurhaus Hotel

The Hotel Royal de Bain was built by Balthasar Neumann in 1739 , later expanded to become the Royal Kurhaus Hotel and finally run as a Steigenberger Kurhaushotel . The hotel was closed on October 31, 2010 after 271 years of operation, when the Free State of Bavaria withdrew from the lease contract due to the 30 million euros required to modernize the building due to fire protection regulations . The Free State and Kissinger City Council wanted a new five-star hotel on the property. Feuring Hotelconsulting GmbH prevailed among the applicants and suggested a partial renovation while preserving the listed building structure. In 2012, the Bavarian State Parliament made available nine million euros to close the funding gaps. Since Feuring did not present a suitable concept, the decision to demolish the hotel was decided and implemented in 2014.

Incorporations

As part of the Bavarian territorial reform of 1972, the then city councilor and later district home administrator Werner Eberth was given the task of supervising the community and handling the regional reform through incorporation contracts. As a result of the reform, eight villages were incorporated: the five nearby suburbs of Arnshausen , Garitz , Hausen , Reiterswiesen and Winkels, some of which have merged with the city center, and three more distant places that do not form a functional unit with the spa town: Albertshausen , Kleinbrach and Poppenroth . In this way, Albertshausen and Poppenroth were able to avoid incorporation into Oberthulba . A few other places that wanted to be incorporated into Bad Kissingen had to join other communities: Waldfenster and Stralsbach were incorporated into Burkardroth because they were too far from the spa town , Wirmsthal went to Euerdorf and Großenbrach to Bad Bocklet . Bad Kissingen grew in July 1972 from 12,429 to 21,916 inhabitants and the area of the city increased enormously to 69 km². While for example not a single place was incorporated into Schweinfurt for purely political reasons and since then the spa town has twice the area than its large neighbor.

However, Bad Kissingen lost its district freedom as part of the regional reform , but was given the newly created status of a large district town . As a result, the Lord Mayor (then Hans Weiß ) was not downgraded to Mayor .

Population development

In the year 1829/1830 the first reliable Kissinger population statistics were compiled, which showed 1,263 inhabitants; In addition to a Catholic majority, this number also included 202 Jews and 2 Lutherans. At the census of December 1, 1910, the district of Bad Kissingen had an area of 12.36 km² and had 5,831 inhabitants. In the census on May 9, 2011 , the city had 20,993 inhabitants.

Religions

The religions in Bad Kissingen differ in their history from other cities in their spectrum, with the typical characteristics of a world bath, comparable to Baden-Baden . Traditionally, the Roman Catholic Church is predominant in Bad Kissingen . Today's Protestant church was only built in the 19th century as a result of the increasing number of Protestant spa guests. For the same reason, an Anglican and a Russian Orthodox Church were established at that time . Bad Kissingen had the first Jewish residents in the 13th century .

Catholic Church

The exact beginnings of the Catholic community in Bad Kissingen are in the dark. The existence of a Kissingen pastor named Symon is proven for the year 1206. There is an almost continuous chronology from him to the current pastor (in the main article above). When Pastor Symon ignored a summons from the papal judges in 1207, he was excommunicated. Thereupon he made an admission of guilt in front of the judges and, among other things, successfully asked for his absolution by providing a guarantee.

From an archaeological point of view, today's Kissingen district of Kleinbrach was home to the St. Dionysius monastery , which was first guaranteed for the year 823, and the floor plans of this monastery were reconstructed during archaeological excavations by the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation between 1989 and 1991. Traces of a church can also be found in the Bremersdorf desert, first mentioned in 1122 and abandoned in 1394 . The Premonstratensian Monastery of Hausen, which was founded by Count Heinrich von Henneberg and is still preserved today, but no longer used as a monastery, was built in the then village and today's Bad Kissingen district of Hausen . The first concrete trace of a Kissingen parish is a document from the year 1286, which speaks of a newly built church; however, it is unclear whether this information refers to the Jakobuskirche or the Marienkapelle . The first reliable evidence for both church buildings date from 1341 for the Jakobuskirche and 1348 for the Marienkapelle. In 1394 the parish came to the Würzburg Monastery and from 1429 was part of the Archdeaconate Münnerstadt.

Due to the increasing number of Catholic spa guests, the Herz-Jesu parish church was built at the end of the 19th century . The status of the parish church passed from the Jakobuskirche to the Herz-Jesu Stadtpfarrkirche .

Protestant church

For a long time there were only a few evangelical citizens in Kissingen. For the year 1578 a "Protestant deacon" named Nicolaus Nicander is guaranteed. The secularization that began in 1803 enabled the evangelical community in the village to grow , also supported by the health resort.

Encouraged by the increasing number of Protestant spa guests, King Ludwig I , who was married to the Protestant Princess Therese von Sachsen-Hildburghausen , commissioned the architect Friedrich von Gärtner , who had built the spa district with the arcade construction in the 1830s on behalf of the king , also with the construction of the Erlöserkirche, consecrated in 1847 and expanded in 1891 . From March 1, 1850, Kissingen was a vicariate ; this became independent six years later and on June 28, 1864 by King Ludwig II raised to a parish. Today the evangelical parish of Bad Kissingen and the surrounding area has around 8,000 members.

Anglican Church

In the second half of the 19th century, due to numerous spa guests from Great Britain, the first plans to build an Anglican church were made. In 1862, the Anglican Church , financed by donations, was inaugurated in Salinenstrasse . The First World War caused a slump in the numbers of spa guests coming from Great Britain. In 1953 the church building was bought by the evangelical community; a year later it was turned into a makeshift parish hall. Due to damage to the foundation, it was demolished in 1968; the Protestant parish hall now stands in its place.

Russian Orthodox Church

The first plans to build a Russian church in Kissingen were made in 1856, but these came to nothing; they wanted to give the building of the church to the Russian Tsar Alexander II on the occasion of his visit to the city, but it did not materialize. As the number of Russian spa guests had increased due to two subsequent spa stays by the tsar in the spa town and a railway line between Russia and Germany, the foundation stone for the Church of Sergius von Radonezh was finally laid on July 20, 1898 .

The First and Second World War brought the Russian community life in Bad Kissingen to a temporary standstill. After the Second World War, the Russian charity "Brotherhood of the Holy Prince Vladimir" moved its headquarters to Bad Kissingen in 1961. Russian religious life in the spa town experienced an upswing through the immigration of ethnic Germans from the former Soviet Union after the fall of the Iron Curtain .

Judaism

There were first Jewish residents in the 13th century . Since the rintfleisch pogrom of 1298 they lived as protective Jews in Kissingen, u. a. of the noble family von Erthal , which led to the ghettoization . The situation only improved with the Bavarian Edict of Jews in 1813 . In 1839 the district rabbinate of Bad Kissingen was established . The Old Synagogue was built in 1851/52 as a replacement for the Jewish house of God built in 1705 . In 1902 the New Synagogue was built on Promenadestrasse as a representative building to host Jewish spa guests. The old synagogue was demolished in 1928. In 1925 the community was one of the ten largest Jewish communities in Bavaria with 504 members .

In 1934, the swimming pool affair caused an international stir when the city council refused to allow Jews to enter the city's swimming pool, as a result of which numerous Jewish spa guests stayed away from the city. The New Synagogue was damaged during the November pogroms in 1938 . Despite repairable damage, the Bad Kissingen city council had it demolished in 1939. In 1942, Jewish residents were deported to Izbica and Theresienstadt , killing 69 Jews from Kissingen.

After the end of the war there were no more residents of the Jewish faith, and the community ceased to exist. Later, 25 Jews lived in the village again. In 1959 a prayer room was built in Promenadestrasse and in 1993 in Rosenstrasse with the Eden-Park health resort, the only kosher- run guest house in Germany.

In 2008, the Bad Kissingen city council decided to lay stumbling blocks in the spa town as part of the Stolpersteine project to commemorate the victims of National Socialism . The Bad Kissinger Stolpersteine citizens' initiative was then formed . In 2009 the first stumbling blocks were laid.

politics

City council

The following were elected to the Bad Kissingen City Council on March 15, 2020 for the 2020 to 2026 electoral period:

|

|

In May 2020, three members of the CSU parliamentary group switched to the DBK, so that the CSU only has six members in the city council, while the DBK has seven.

City leaders

| Surname | Official title | Term of office |

|---|---|---|

| Donat foot | City Council | 1847-1854 |

| Gerhard Linhard | 1854-1865 | |

| Carl Fleischmann | Voluntary interim city council | 1865-1866 |

| Valentin Fuchs | Legally qualified mayor | 1866-1869 |

| Gottlieb Full | 1869-1878 | |

| Josef Feldbauer | 1879 | |

| Carl Prince | 1879-1882 | |

| Theobald von Fuchs | 1883-1917 | |

| Eduard Bauch | 1917-1919 | |

| Max Pollwein | 1919-1939 | |

| Adalbert Wolpert | Lord Mayor | 1939-1944 |

| Franz Meinow | 1945-1946 | |

| Franz Rothmund | 1946-1947 | |

| Karl Fuchs | 1947-1952 | |

| Hans White | 1952-1984 | |

| Georg Straus | 1984-1990 | |

| Christian Customs | 1990-2002 | |

| Karl Heinz Laudenbach | 2002-2008 | |

| Kay Blankenburg | 2008-2020 | |

| Dirk Vogel | from 2020 |

coat of arms

Blazon

In silver a red gate-castle with three tinned towers, the middle one with a blue helmet and covered with a shield divided by black and silver; in it a cut off griffin claw in mixed up colors. The claw comes from the Henneberger family in Bad Kissingen.

Coat of arms history

Kissingen received city rights during the rule of the Counts of Henneberg before 1280, who had owned it since 1234. There are no known seals for the period before the 16th century.

The oldest known seal already shows today's coat of arms: a gate castle with a closed gate and three towers, the middle tower is covered with a shield with the coat of arms of a branch line of the Truchsesse von Henneberg . At this time Kissingen was already part of the Würzburg Monastery , which it had come to in 1394 through Count Swantibor from Pomerania and the Burgraves of Nuremberg and which remained until the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1803. Details of the coat of arms representations changed over the centuries. The coat of arms of the Truchsesse von Henneberg was a black hen foot on a golden background. This coat of arms led the city until 1927.

In 1927, the main mint in Munich added the similar coat of arms of the Lords of the Kehre, a shield divided by black and silver with a hen foot in confused colors, to the city seal without a resolution by the city. The bug was not noticed. Since then, the city has had the coat of arms in this form.

Town twinning

Bad Kissingen maintains city partnerships with:

-

Austria : Eisenstadt , approx. 700 km away

Austria : Eisenstadt , approx. 700 km away -

Italy : Massa , approx. 900 km away

Italy : Massa , approx. 900 km away -

France : Vernon , approx. 800 km away

France : Vernon , approx. 800 km away

Culture and sights

Bad Kissingen, with its spa buildings and spa facilities, the valley of the Franconian Saale and the wooded mountains of the Vorrhön, forms an almost intact overall picture.

The spa has extensive parks and numerous buildings from two stylistic epochs: classicism and the typical architectural style of European spas of the Belle Epoque , historicism . In the small, historic city center from the Middle Ages , north of the spa district, many old buildings on the main fronts have also been replaced by larger historic buildings. As a result, there are hardly any medieval structures left and almost the entire place has the character of a traditional spa town.

Museums

-

Museum Upper Saline

- Department "Bismarck Museum"

- "Toy World" department

- Department "Salt and Salt Production"

- Department "Heilbad Kissingen"

- Department "Weltbad Kissingen"

- Cardinal Döpfner Museum in Hausen Monastery

- Heimatstube Reiterweise

- Permanent exhibition "Jewish life in Bad Kissingen" in the Jewish community center

orchestra

Spa orchestra

The first beginnings of the Kissinger Kurmusik lie in the dark and are first attested in the 17th century . Prince-Bishop Johann Philipp von Schönborn had his own ensemble from 1642 and also traveled with them to Kissingen. The year 1899 brought a turning point for the Kissinger Kurmusik with the engagement of the Kaim Orchestra, the later Munich Philharmonic , under Franz Kaim . In the summer months, the ensemble provided the spa orchestra with 45 members until in 1905 the Bavarian Ministry of Finance found itself unable to pay the musicians, so that from 1906 the Wiener Konzertverein , the predecessor orchestra of today's Wiener Symphoniker , took over its function. In 1919 the Munich Philharmonic returned as the orchestra of the Munich Concert Society. From 1952 to 1979 the Hofer Symphoniker took the spa orchestra to new heights. Since then, with 13 musicians in permanent employment all year round, it has been one of the largest spa orchestras of all 350 German spa towns. In 2012 it got an entry in the Guinness Book of Records for the orchestra with the most appearances per year with 727 annual appearances . In 2018 the spa orchestra was renamed Staatsbad Philharmonie Kissingen .

Youth Music Corps

The youth music corps of the city of Bad Kissingen is a figurehead of the spa town. It has already had many international appearances, including overseas, and has often marched with the Oktoberfest parade in Munich and even led it in 2014. The wind orchestra consists of over 80 young people between the ages of ten and 20.

Buildings

overview

The existence of a superioris salina is known as early as 823 at the location of today's Lower Saline . The castle ruin Botenlauben , built around 1180, towers over the town (see picture: Middle Ages ). In 1738, master builder Balthasar Neumann drew the general view of the late medieval Kissingen with a thick city wall and 14 towers on a square of 240 by 240 meters.

Today, the old town and the spa district form two very different urban dimensions: the medieval settlement that was expanded into a town in the 13th and 14th centuries and the adjoining spa district on the Bruchbtrett, which was planned from the 18th century . The dividing city wall between the two areas, which ran along the south side of Grabengasse to the fire tower, disappeared completely here. Before that, Ludwigstrasse was laid out as the new main street of the town that had been expanded into a spacious spa town. In addition, many old houses on the main fronts within the old town were replaced by large historicist buildings during the Wilhelminian era . So go both areas since its own symbiosis and are available as pooled ensemble of buildings under monument protection .

Spa buildings

The spa district developed through the location of the fountains at the southern exit of the old town main street (today's Untere Marktstraße ). The largest ensemble of historical spa buildings in Europe was built in three stages by three master builders under the aegis of the following three rulers:

- Friedrich Karl von Schönborn-Buchheim , Prince-Bishop of Würzburg and Bamberg (1729–1746)

- Ludwig I , King of Bavaria (1825–1848)

- Luitpold of Bavaria , Prince Regent of Bavaria (1886–1912)

First stage from 1737 to 1738 by Balthasar Neumann :

The Franconian Saale was relocated, the new spa garden created and the conditions for the entire subsequent structural development of the spa district created (see: Ascent to the Weltbad ). However, at the same time Neumann planned a very petty Kurhaus, which was sharply criticized by contemporaries and was later demolished and replaced (see: Königlichen Kurhaushotel ).

Second stage 1834 to 1842 by Friedrich von Gärtner :

As a result of the new spa garden, the Saale bridge had to be relocated to the north, using the new Ludwigsbrücke (1836–1837). The arcade building in the style of the Florentine early Renaissance (1834–1838) with the associated Rossini hall , 200 m long in development, was the first building on the platform created by Neumann. Then the jug magazine (1839) and finally the open fountain hall (1842), in sharp contrast to the southern end of the arcade building, which impressively illustrates Gärtner's architectural development. It was the first civil engineering structure in Bavaria and at the same time one of the first cast-iron skeleton structures in Germany.

Third stage 1910 to 1913 by Max Littmann :

The foyer (1910–1911) was built in the classic Art Nouveau style south of the arcade after a long break in construction . With a length of 90 m and an area of 2,640 square meters, it is considered the largest foyer in Europe. With its cross-shaped floor plan and a nave , with an interior divided by rows of columns, it was laid out in the manner of a basilica . The innovative building was built in just eight months using a modern reinforced concrete construction, with a revolving stage for the spa orchestra, usable for both the interior and the spa garden (see photo: spa orchestra ). The new fountain hall was integrated into the west wing, replacing the first one that was demolished in 1909.

The Regentenbau (1911–1913) north of the arcade building, in neo-baroque style , was built in place of a spa park and became the town's landmark. Littmann completed the huge building ensemble in the spa district with the classically elegant social and event center, which today also serves larger congresses, with a vestibule , large hall (Max Littmann hall) , green hall and white hall . The guests' carriages and automobiles can still drive into the open lobby. In a broader sense, the Regentenbau also includes a jewelry yard , reading and gaming rooms and a spa garden cafe.

West Saale-Ufer 1868 to 1906:

The Luitpoldbad (originally: Aktienbad ) in neo-renaissance by Albert Geul (1868–1871, added 1902–1906) is 130 by 80 meters. The north wing (1878–1880) was completed by Heinrich von Hügel and Wilhelm Carl von Doderer . Today the Luitpold Casino of the Bavarian State Casinos is located in it . Around 1900 the Luitpoldbad with its 236 bathing cabins was the largest bath in Europe. At the beginning of the millennium, Hilton showed interest in converting the huge, vacant complex into a hotel, which failed because of immense costs in connection with monument protection . In 2018, the general renovation was completed for a new use of the Free State as an event location and administrative center for 39 million euros.

- Arcades and halls of the regent building

For more pictures of the spa buildings, see: Salt pans, mineral springs and spa district

More profane buildings

From the city wall, which was built around 1350, a section at Eisenstädter Platz and a corner tower have been preserved, the fire tower from the 15th century . The old town hall (1577) on the market square is a renaissance building . The Heussleinscher Hof (1709) on today's Rathausplatz by Johann Dientzenhofer was a baroque aristocratic seat, and since 1929 the New Town Hall . The Upper Saline (1763) was built by Prince Bishop Adam Friedrich von Seinsheim for salt production.

The Collard house (around 1835) at the Kurgarten is a classicist hotel building that became a Grand Hotel around 1900 under Gustav Collard (today a commercial building). The Hotel Kaiserhof Victoria across from the Wandelhalle was created by combining two classicist hotel buildings: the Hotel Victoria (1836, in the south) by Johann Gottfried Gutensohn and the Kaiserhof (1840, in the north). The long hotel front from the Biedermeier period characterizes the main street of the Kurviertel. The Ballinghaus in Martin-Luther-Straße and the Westendhaus in Bismarckstraße were both built in 1840 in the classical style by Gutensohn. The station (1874) in neo -renaissance is by Friedrich Bürklein . The Bismarck monument (1877) in the Hausen district by Heinrich Manger was the first monument to be erected in honor of the Chancellor. The Kleinbracher arch bridge over the meadow in the Franconian Saale has 18 arches. The Villa Messerschmitt (1894) at the spa garden in historicist style with a magnificent decor by Karl Weinschenk was built as a coffee house with a hotel. The Dapper Sanatorium (1894, today: Dappers Hotel ) in Menzelstraße, in neo-renaissance with different colored sandstone , was designed by Carl Krampf (see picture: Bavarian Kingdom ). The house at Marktplatz 18 (1897) in the Flemish - Baroque style also comes from Weinschenk. The Villa Montana (1897, today: Haus Bethania ) by M. Renninger in Menzelstraße has massive roof shapes that are otherwise untypical for the Neo-Renaissance. The so-called Peters Burg (1898) is a neo-renaissance villa by Krampf on Maxstraße. The former sanatorium Dr. Dietz (around 1900) in the neo-renaissance style is equipped with iron balconies typical of spa hotels. The Neo-Renaissance Villa Hailmann (1903) in Kurhausstrasse was designed by Antony Krafft . The Kurtheater (1905) in Art Nouveau style was planned by Max Littmann, who built the foyer and regent building. The house Marktplatz 10 (1907) by Krampf is a sandstone building in Art Nouveau style, which, in contrast to the Wilhelminian era, aims for a plastic effect. The Wittelsbach Tower (1907) on the Scheinberg in the style of a monumental monument is also by Krampf. The Hotel Krosse (1908) in Ludwigstrasse in the Baroque Art Nouveau style by Anton Eckert is an example of the urban Art Nouveau that replaced the Biedermeier in Bad Kissingen. The Littmannhaus (1908) is a residential and commercial building in the classicizing Art Nouveau style that Littmann planned in the context of the subsequent, neighboring Regentenbau. The house Marktplatz 8 (1910) in Art Nouveau style, by Adolf Gögel , forms an assembly group with the neighboring house Marktplatz 7 . The house at Hartmannstrasse 26 (around 1910) by the Berlin architect Heinrich Möller is a four-storey Art Nouveau apartment building with elements that are characteristic of houses in large cities. The market square 17 (1912) in the classifying Art Nouveau by Krampf is another example of the structural development in the old town, especially on the market square, where smaller houses were replaced by larger buildings in the period after 1900. On the Sinnberg , the construction of the massive Bismarck Tower by Wilhelm Kreis dragged on from 1914 to 1926 due to the interruption of the First World War . The Städtische Schlachthof (1925) by Joseph Hennings , popularly known as the Ox Cathedral , which has not been in use since 2001 , has incorporated elements of New Building and Art Nouveau. A subsequent use as a market hall was under discussion. The Kurhausbad (1927) in the Prinzregentenstrasse, in the classical style, by Littmann, was the largest such facility in Europe when it opened. In the meantime, like all structures previously listed under monument protection standing terrace swimming pool (1954) on Finsterberg of Anton Koller and Hans-Joachim Haberland has granted a pane of glass in the pool wall, outsiders a peek under water and Kissingen first modern landmark, because Café Pavilion . The second modern landmark of the spa architecture followed with the KissSalis Therme (2004) in the Garitz district by Kenéz + Jaeger (see picture: present ).

- More profane buildings

Churches

- The Catholic Church of St. Jakobus (vernacular: Jakobi Church ) was the old Catholic parish church in Kissingen. The tower dates from the 14th century, the square nave (1772–1775) was built by Johann Philipp Geigel in the classical style.

- The Catholic parish church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus was built in neo-Gothic style in 1882 by Andreas Lohrey . Its tower is 67 meters high (see picture: Catholic Church ).

- The choir and tower basement of the Marienkapelle in the chapel cemetery date from the 15th century . The nave was built in the 18th century according to Balthasar Neumann's plans . The baroque interior was designed by Benedikt Lux from Bad Neustadt .

- The Evangelical Lutheran Church of the Redeemer was built in 1847 according to plans by Friedrich von Gärtner and expanded in a neo-Romanesque style by August Thiersch in 1891 .

- The Russian Orthodox Church of St. Sergius von Radonezh (1901) in neo-Byzantine style by Viktor Schröter (St. Petersburg) was built under the supervision of Carl Krampf for the then very numerous Russian spa guests. The church is supported by the brotherhood of the Holy Prince Vladimir (see picture: Russian Orthodox Church ).

In addition to the churches in the city center, there are other places that were incorporated in 1972.

Parks and natural monuments

- Klaushof Wildlife Park , four kilometers northwest

- Picture oak near Albertshausen

- Fragrance Forest (Bad Kissingen)

- Cascade Valley

- Luitpold Park

- rose Garden

- Ballinghain with Finsterberg

- Liebfrauensee with chapel cemetery (cemetery park)

- Path of reflection

- Eiringsburg

- Wichtelhöhlen (Euerdorf)

See also: Seven Mountains

Sports

Bad Kissingen has the classic sports profile of a spa town. Football plays a subordinate role, while equestrian sports and golf have shaped sporting life for 100 years, and more recently ice hockey too .

- Bad Kissingen Golf Club . It was founded in 1910 and is the second oldest golf club in Bavaria with the oldest golf course in the Free State (1911). It is located in the Saale valley south of the spa town.

- Bad Kissingen equestrian club . He had his domicile in Tattersall from 1930 (with the war interruption) to 1987 . In the 1920s, a tournament building with a 100 m long spectator stand was built in the Oberen Au for riding and driving tournaments. Racing was not resumed after the Second World War. The RV Bad Kissingen organizes the annual Rakoczy horse show here . After the war, the Bad Kissingen airfield was also built here, and since then there has been a combined tournament and airfield.

- 1. FC 06 Bad Kissingen . It is the city's top football club (Lower Franconia District League).

- Gymnastics and Sports Club Bad Kissingen 1876 e. V. It has (as of 2018) 1,051 members and over 15 departments.

- Tennis Club Rot-Weiß Bad Kissingen. It has 10 sand and 2 indoor courts; top-class team are the men 50 (Bayernliga).

- Rifle club Edelweiß Reiterswiesen (with air pistol ). He is in the Bayern League.

societies

There are a number of associations in Bad Kissingen, including:

- the boy scouts with their youth work

- the Catholic young community with its youth work, especially the annual summer camp with the acolytes

- there is also the Mfg-Bad Kissingen e. V.

- The Bad Kissingen section of the German Alpine Club founded on December 7th, 1906 with 2,400 members (as of December 31, 2018) looks after the Bad Kissinger hut in the Tannheimer mountains and the DAV climbing hall Bad Kissingen "No Limits".

- The Rhönklub has a branch in Bad Kissingen which will take place on 5./6. August 1876 was founded. This has (as of: 2019) 347 members, operates the hiking trail: Hochrhöner which is 135 km long, the Kissinger hut (not to be confused with the Bad Kissinger hut). The fire tower in Bad Kissingen is also part of the section.

Regular events

- The Rákóczi festival is the classic of Kissingen, a historical city festival with a parade on the last weekend in July.

- The Kissinger Sommer is a four-week international music festival from mid-June to mid-July. In order to give the city's cultural activities new impetus, the Kissinger Sommer took place for the first time in 1986 as part of the zone border funding . The music festival, in which artists like Cecilia Bartoli , Lang Lang or David Garrett mainly give classical concerts, has acquired a worldwide reputation over the years.

- The Kissinger Winterzauber was created in 1999 as a counterpart to the Kissinger Sommer. The four-week music festival of the same kind takes place from the beginning of December to the beginning of January.

- The Kissinger Piano Olympics is an international piano competition for young talents in September and October.

- The free & outdoor music festival for the younger generation takes place in June.

- Minnesang and Schwerterklang is a medieval knight spectacle on the castle ruins of Botenlauben on the third weekend in September.

- The ZF Sachs Franken Classic is an annual vintage car rally at Whitsun.

- Adventure & Allrad is the largest off-road trade fair in the world. It has been organized by the company pro-log GmbH since 1999 on the former missile base of the US Army in the Reiterswiesen district , with over 200 exhibitors and over 50,000 visitors.

- The Bad Kissingen Triathlon is an open triathlon event in the spa gardens at the beginning of September.

- The Kissinger Easter Sounds are a series of events with concerts, plays, readings and thematically conceived church services by the Protestant and Catholic Church.

Culinary specialties

The Kissinger is a buttered Danish pastry in the shape of a croissant with a jam or hazelnut filling . Taking the healing water in the spa facilities before breakfast gave the Kissinger bakers the idea of offering specialties like Kissinger . Fine bakers (Meisner, Memmel, Messerschmidt and Zoll) set up stalls in the spa garden.

The Kissinger wafers have been around since 1928 and have been made by the Zintl family since 1937. The family company was founded by Alois Zintl. Originally the wafers from Karlsbad come as Karlsbad wafers . The Kissinger wafers are less sweet than their models from the Bohemian spa triangle .

Economy and Infrastructure

traffic

Bridges and footbridges

Bad Kissingen has, including areas in which the city limits run in the middle of the river, five road bridges and twelve footbridges over the Franconian Saale. Two of these are on the golf course, one of which is not open to the public. The footbridge at the Swiss house was specially designed for horses (non-slip).

Road traffic

The B 286 (Schweinfurt - Bad Brückenau ) and the B 287 ( Hammelburg - Münnerstadt ) run through the city . The next motorways are the A 7 ( Kassel - Fulda - Würzburg ) and the A 71 ( Erfurt - Schweinfurt).

air traffic

The airport Bad Kissingen is located on the Upper Au , one kilometer north of the spa.

Public transport

Stagecoach

From April to October the only stagecoach line from Bad Kissingen to Bad Bocklet still in operation by Deutsche Post in Germany exists .

bus

In addition to several regional bus routes that lead into the district, several city bus routes open up all parts of the city. The lines are used by the KOB and the OVF . The tourist card is valid as a ticket on the city bus routes throughout the city. Eight city bus routes and two additional routes are privately operated by the Weltz company.

shipping

The Saaleschifffahrt GmbH operates a passenger ship between Rosengarten and Unterer Saline .

rail

The Bad Kissingen Train Station is a railhead on the Franconian Saale Valley Railway and provides connection to the transport network of the Deutsche Bahn and the Erfurt train . The trains from Bad Kissingen in the direction of Ebenhausen all continue to Schweinfurt Hauptbahnhof or even further to Schweinfurt Stadtbahnhof. From Schweinfurt Hbf there is a regional express connection to the two neighboring ICE stops in Würzburg and Bamberg . There are also direct regional express connections between Bad Kissingen and Würzburg. In Gemünden there is a connection in the direction of Frankfurt or Fulda, in Ebenhausen in the direction of Meiningen and Erfurt.

Public facilities

In Bad Kissingen there is a branch of the medical service of the health insurance and an office of the office for food, agriculture and forestry . Furthermore, the central cash desk of the Bad Kissingen tax office is located in Bad Kissingen, which collects taxes for the Bad Kissingen, Bad Neustadt an der Saale , Lohr am Main , Obernburg am Main and Aschaffenburg tax offices . The central cash desk is located around the newly built Luitpoldbad.

Established businesses

- pro-log with the off-road trade fair Adventure & Allrad

- Franken Brunnen with the mineral water Bad Kissinger

- Saale-Zeitung (Kissinger Verlagsgesellschaft), subsidiary of the Oberfranken media group since 2010

- Heiligenfeld Kliniken , group of companies with several specialist clinics

- Laboklin , laboratory for clinical diagnostics

RS (Dr. Rudolf Spitaler) was a company for model railway construction and in the 1950s a well-known brand name for model construction for model railway systems of the H0 gauge .

education

- KISSori learning center - children's house, elementary school, high school http://www.kissori.de/

- Anton Kliegl secondary and middle school

- State secondary school Bad Kissingen

- Jack Steinberger High School

- State vocational school Bad Kissingen with vocational school for hospitality professions

- Rhön-Saale start-up center (RSG) with a bachelor's and master's degree in health management

Personalities

See also

- Boxberger Prize Bad Kissingen

- Kissingenviertel

- Kissinger (pastries)

- Theresienspital Foundation

- Salt production in Hausen

- Otto von Bismarck in Bad Kissingen

literature

(in chronological order)

- Johannes Wittich : Aphoristic extract and brief report of the mineral Sauerbrun in Kissingen, in the Principality of Francken, of its strength and effects. (Provided by Iohannem Wittichium Reipublicæ Arnstadianæ Medicum). Georg Baumann printing works, Erffurdt (Erfurt) 1589.

- Johannes Bartholomäus Adam Beringer : Thorough and most correct examination of their Kißinger Heyl and health fountain. Würzburg 1738 ( digitized version ).

- Franz Anton Jäger: History of the town of Kissingen and its mineral springs. Ingolstadt 1823 ( digitized ).

- Johann Adam Maas: Kissingen and its healing springs. 2nd increased edition. Franz Bauer, Würzburg 1830 ( digitized version ).

- JB Niedergesees: Description of Kissingen and its surroundings. Bad Kissingen 1844 ( digitized ).

- Franz Anton von Balling : The healing springs and baths in Kissingen for spa guests. 3. improved edition. Verlag August Osterrieth, Frankfurt am Main / Kissingen 1850 ( digitized version ).

- FJ Reichardt: Kissingen address book. With a brief history of Kissingen. Self-published, Kissingen 1865 ( digitized version ).

- Albert Guttstadt: Hospital Lexicon for the German Empire. The institutional welfare for the sick and the infirm and the hygienic facilities of the cities in the German Empire at the beginning of the twentieth century. Reimer, Berlin 1900, pp. 575-576 ( digitized in the Internet Archive ).

- Kissingen . In: Meyers Großes Konversations-Lexikon . 6th edition. Volume 11, Bibliographisches Institut, Leipzig / Vienna 1907, pp. 75–77 .

- Anton Memminger : Kissingen - history of the city and the bath. Memminger brothers, Würzburg 1923, DNB 575068221 .

- Walter Mahr: History of the City of Bad Kissingen. City of Bad Kissingen, Bad Kissingen 1959, DNB 453180302 .

- Ernst-Günter Krenig: A bathing trip to Kissingen in 1811. In: Frankenbund (Hrsg.): Frankenland - magazine for Franconian cultural studies and culture. Born in 1965. Frankenbund, Würzburg 1965, ISSN 0015-9905 , pp. 150–159 ( digitized version ).

- Franz Warmuth: 100 Years of the Herz Jesu Parish Bad Kissingen - Contribution to the history of the Parish Bad Kissingen. Bad Kissingen Catholic Parish Office, Bad Kissingen 1984, DNB 99534597X .

- Hans-Jürgen Beck, Rudolf Walter: Jewish life in Bad Kissingen. City of Bad Kissingen, Bad Kissingen 1990, DNB 911057900 .

- Winfried Schmidt: Bad Kissingen and its guests - rather irrelevant verses. Schachenmayer, Bad Kissingen 1992, ISBN 3-929278-00-6 .

- Denis André Chevalley, Stefan Gerlach: City of Bad Kissingen. (= Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation [Hrsg.]: Monuments in Bavaria . Volume 75, 6/2). Karl M. Lipp Verlag, Munich 1998, ISBN 3-87490-577-2 .

- Werner Eberth : Bismarck and Bad Kissingen. Theresienbrunnen-Verlag, Bad Kissingen 1998.

- Georg Dehio , Tilmann Breuer: Handbook of German art monuments . Bavaria I: Franconia - The administrative districts of Upper Franconia, Middle Franconia and Lower Franconia. 2nd, revised and supplemented edition. Deutscher Kunstverlag, Munich / Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-422-03051-4 , pp. 68–72.

- Gleb Rahr : One hundred years of the Russian Church in Bad Kissingen. Kunstverlag Fink, Lindenberg 1999, ISBN 3-933784-04-2 .

- Thomas Ahnert, Peter Weidisch (eds.): 1200 years Bad Kissingen, 801–2001, facets of a city's history. (= Festschrift for the anniversary year and volume accompanying the exhibition of the same name / special publication from the Bad Kissingen City Archives). Verlag TA Schachenmayer, Bad Kissingen 2001, ISBN 3-929278-16-2 .

- Peter Ziegler: Celebrities on promenade paths. Emperors, kings, artists, spa guests in Bad Kissingen. Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh, Würzburg 2004, ISBN 3-87717-809-X .

- Birgit Schmalz: Salt and salt production. (= Bad Kissinger Museum Information. Issue 1). Verlag Stadt Bad Kissingen, Bad Kissingen 2008, ISBN 3-934912-09-5 .