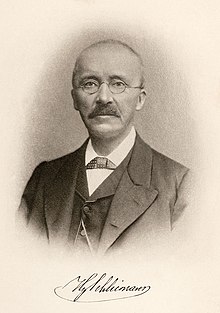

Heinrich Schliemann

Johann Ludwig Heinrich Julius Schliemann (born January 6, 1822 in Neubukow , † December 26, 1890 in Naples ) was a German businessman , archaeologist and pioneer of field archeology . He was the first researcher to carry out excavations in Hisarlık, Asia Minor, and found the ruins of the Bronze Age Troy that he and other researchers, above all Frank Calvert , suspected to be here .

Life

Adolescence

Heinrich Schliemann was born in Neubukow in the (partial) Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin as the fifth of nine children of pastor Ernst Johann Adolph Schliemann (1780-1870) and his wife Louise Therese Sophie Schliemann (1793-1831), daughter of the future mayor of Sternberg , born. Because his father took over the lucrative pastoral position in Ankershagen in May 1823 , Schliemann grew up in that village in East Mecklenburg and spent his childhood there until he was ten years old. In 1828 he received, according to his own account in his autobiography, published in 1879, as a Christmas present Die Weltgeschichte für Kinder from Georg Ludwig Jerrer , from which his father read to him. According to his own statements, this gave rise to his decision to search for the ancient city of Troy.

Heinrich Schliemann's mother died in 1831, nine weeks after the birth of the ninth child; therefore Heinrich came into the family of his uncle Friedrich Schliemann (1790–1861), who was pastor in Kalkhorst near Grevesmühlen at the time, in January 1832 . When Schliemann's father was relieved of his office due to significant differences with his parish in Ankershagen and was unable to pay the school fees for the Carolinum grammar school in Neustrelitz , Heinrich Schliemann had to break off the Abitur after just three months and switch to the Neustrelitzer Realschule, which he - as was customary at the time - visited until he was 14 years old. At Easter 1836 he began an apprenticeship as a commercial assistant to two merchants in Fürstenberg / Havel , who ran the same grocer there one after the other. After completing his apprenticeship at Easter 1841, Schliemann was determined to leave Fürstenberg and emigrate to North America with a school friend. He was no longer interested in job offers in Fürstenberg and by Johannis 1841 Schliemann was unemployed. He visited his father, who was now his second marriage and lived in Rostock-Gehlsdorf, and used his stay in Rostock to attend a commercial school and to cure his lung disease in a hydropathic institute.

Commercial career

In September 1841 Schliemann left Mecklenburg for good and tried his luck in Hamburg , but despite several letters of recommendation he was only able to get one job as a warehouse worker and fell seriously ill. Completely impoverished, like many contemporaries, he now thought of emigration , took a job in La Guaira in Venezuela and set out on November 28, 1841 in bad weather with the three-master Dorothea . However, the ship ran aground on 11/12. December off the Dutch island of Texel . On December 20, he arrived in Amsterdam , at the end of the year he got a job as a clerk at the trading house Hoyack & Co. and began to learn foreign languages, which apparently was extremely easy for him. Within a year he learned Dutch, Spanish, Italian and Portuguese.

In 1844 he got a position in Hamburg at BH Schröder & Co. as a correspondent and accountant, later head of the correspondence office, and began to learn Russian - probably due to the close commercial ties between his employer and the Russian Empire. In 1846 he was sent to St. Petersburg as an agent for the trading house renamed Schröder Gebrüder & Co .; a year later he opened his own trading house there on Nevsky Prospect and acquired Russian citizenship (February 15, 1847). In St. Petersburg he stayed in the palace of Count Sievers and was already keeping a servant. Schliemann was particularly successful in trading with so-called colonial goods , namely dyes (especially indigo ) and luxury foods, as well as with industrial raw materials.

The correspondence with his brother Ludwig, who was a gold prospector in California , drew Schliemann to America from 1850 to 1852. He founded a gold trading bank in Sacramento and began successfully investing in American railroad projects. Back in Europe, he married the Russian merchant's daughter Yekaterina Petrovna Lyschina (1826-1896) in the St. Isaac's Cathedral on October 12, 1852 according to the Russian Orthodox rite, thereby consolidating his social position. The marriage had the three children Sergei (1855–1941), Natalja (1859–1869) and Nadeschda (1861–1935).

He became very rich through large deliveries of ammunition raw materials (lead, sulfur and saltpeter ) to the tsarist army in the Crimean War (1853-1856) while skilfully bypassing the sea blockade by land. In his economically most successful year (1855), Schliemann was listed on the Petersburg Stock Exchange as a businessman with the highest trading turnover and a business volume of 1 million thalers .

Researcher life

1864 to 1870

From 1856 he learned Latin and ancient Greek and wanted to retire from business life. He only succeeded in doing this in 1864; that year he went on extensive study trips to Asia and North and Central America. In 1865 he wrote his first book: La Chine et le Japon (China and Japan). With its precise, factual description, the book is a good source of knowledge about the premodern everyday life in these two countries. From 1866 on he studied languages, literature and archeology at the Sorbonne in Paris.

In April 1868 Schliemann began his first research trip to Greece. He traveled to Corfu via Rome and Naples and looked for traces of the Phaeacians , where Odysseus, according to Homer , was stranded and whose land Scheria was often equated with Corfu. On July 28, 1868, he reached Ithaca and spent nine days looking in vain for the palace of Odysseus described in the Iliad . For the first time he tried his hand at digging and hired local helpers. After brief stays in Corinth and Athens , he reached the Troad for the first time on August 9th and carried out intensive research on the presumed location of the legendary city of Priam . After long, detailed on-site visits, he shared Frank Calvert's opinion that the castle should be hidden under the Hisarlık , and applied to the Sublime Porte for excavation permission .

In September 1868 Schliemann traveled back to Paris and wrote his book Ithaka, der Peloponnes und Troja , which he presented to the University of Rostock as a dissertation in 1869 together with his publication La Chine . In the same year he traveled to St. Petersburg and the USA, where he received American citizenship on March 29 and obtained a divorce on June 30, his Russian Orthodox marriage, which was indissoluble in Europe at the time. At the same time he was absent from the Philosophical Faculty of the University of Rostock as Dr. phil. PhD . The doctoral certificate was issued on April 27, 1869 in Latin.

At the same time, he had his friend Archbishop Theokletos Vimpos from Athens send him photographs of Greek marriage candidates and, after his return to Greece, married the 17-year-old Sophia Engastroménos on September 24, 1869 according to the Greek Orthodox rite in the Meletios Church in Kolonos , his birthplace of Sophocles (now part of Athens). After a honeymoon through Italy and a stay in Paris, the Schliemann couple returned to Athens in early 1870 and bought a villa in Odos Mouson near Syntagma Square . In the same year the Greek Philological Society in Constantinople elected him as a corresponding member.

1870 to 1873 (Troy)

In the spring of 1870, the Ottoman government's excavation permit had still not been received, but Schliemann drove again to Troy and from April 9-22 dug a 20-meter-long and up to 3-meter-deep search trench with unskilled workers, which had already led to the discovery of several layers of settlement . In December he made a trip to Constantinople and made an unsuccessful attempt to obtain permission to excavate from the Ottoman authorities in person. During these three weeks he learned Turkish . On May 7, 1871, his daughter Andromache († 1962) was born in Athens. When he was in London in the summer to buy parts of the excavation equipment, he received a letter from Constantinople on August 12 with the excavation permit.

Back in Troy, the local provincial administration only recognized the permit for the part of the Hisarlık that belonged to Frank Calvert, which would have prevented an overall cut through the hill. After the intervention of the American embassy in Constantinople, the excavation campaign could begin as planned on October 11, 1871 and quickly unearthed ancient, Bronze and Stone Age settlement layers until the excavations had to be ended on November 24 because of the onset of winter. The second campaign began on April 1, 1872 and on June 13 led to the discovery of the most significant find to date, the so-called Helios metope from the triglyph frieze of the Hellenistic Temple of Athena (today part of the Berlin Collection of Antiquities in the Altes Museum ).

The third and most successful excavation campaign began in January 1873. Schliemann discovered a city gate (in his interpretation the Scaean Gate of the Iliad), from which a wide street leads to a house he interpreted as the palace of Priam , near which on May 31st the so-called Priam's treasure was found. Schliemann declared Troy had been found and his task had been fulfilled. Nevertheless, the German scientists continued to refuse him the desired professional recognition, in particular the German archeology luminary Ernst Curtius , with whom Schliemann competed (unsuccessfully) for the excavation rights for Olympia . Only in Great Britain did the find attract a lot of attention in the professional world; the Society of Antiquaries of London invited Schliemann to a highly acclaimed lecture at Burlington House , where he was greeted with a laudatory speech by the British statesman William Ewart Gladstone .

1874 to 1876 (Mycenae)

At the beginning of 1874 Schliemann traveled to Mycenae to continue researching for traces of the people and places mentioned in Homer's Iliad , in particular for the grave of Agamemnon , which he suspected to be in Mycenae. For six days he had twelve workers dug a five-meter-deep search trench on Acropolis 34 until the illegal excavation was ended by the authorities. In the same year Schliemann was sued by the Hohe Pforte for the surrender of half of his Trojan treasures in an Athens court; the trial ended with a settlement in which Schliemann against payment of 50,000 gold francs to Priam's Treasure legally acquired.

While waiting for the excavation permit for Mycenae, pulled Schliemann in 1875 to lecture and museum tour of Europe and led excavations at Alba Longa (in Roman mythology was founded by Ascanius , son of the Trojan prince Aeneas from the Iliad ) and formerly Phoenician Mozia by .

In the summer of 1876 the excavation permit was available for Mycenae, so that he and his wife Sophia, who for the first time independently led partial excavations here, officially began the extensive campaign with 63 workers on August 7th. On September 9th they came across a meeting place mentioned in the Iliad consisting of two concentric rings made of upright, flat, polished stone slabs with an outer diameter of around 30 meters. During test excavations at this point, simple grave steles and grave attachments came to light. On October 9th the work was interrupted due to the announced visit of the Brazilian Emperor Dom Pedro II and the emperor was received on October 25th at the excavation area. From the end of November, well-furnished graves came to light in the middle of the stone circles, and finally five magnificent shaft graves with golden death masks and valuable grave goods, e. B. a life-size silver cow's head with golden horns. On November 28th, Schliemann telegraphed the Greek king that he had found the grave of Agamemnon and his family. It wasn't until the next day, however, that he found the largest and most elaborate golden death mask, which has come to be known as the gold mask of Agamemnon . He continued the excavations until December 3rd. By then he had lifted 13 kilograms of gold treasures. These were stored by the Greek authorities in the State Bank of Athens and can be seen today in the National Archaeological Museum .

The grave goods also included numerous artifacts in which amber was used. Schliemann had the amber examined by the Danzig pharmacist Otto Helm , who came to the conclusion that it was Baltic amber. This led to a discussion, which has not yet been fully completed, on the age, the course and the ramifications of the trade routes between the peoples who settled in the Baltic Sea region and the ancient cultures in the Mediterranean (see Amber Road ) as well as on the question of the geographical origin of amber can be reliably determined from archaeological excavations.

1877 to 1890

In November 1877 Schliemann brought his Priam's treasure to London, exhibited it in 24 showcases for three years in the South Kensington Museum and became an honorary member of the Society of Antiquaries of London . Now scientific and public interest in Schliemann's work in the German Reich increased. In March 1878 his son Agamemnon († 1954) was born.

In 1878/79 Schliemann carried out new excavation campaigns in Troy, with his sponsor Rudolf Virchow being present from 1879 onwards. At the same time, Ernst Ziller built the neoclassical residential palace Iliou Melathron for Schliemann in Athens . In 1880/81 Schliemann dug in Orchomenos (whose people, according to Homer, took part in the war against Troy under their king Ialmenos ) and found the so-called treasure house of Minyas , the legendary founder of the city. In 1881, through Virchow's mediation, Schliemann gave his collection of “Trojan antiquities” to the German people and became an honorary citizen of Berlin and an honorary member of the Berlin Society for Anthropology, Ethnology and Prehistory . He published his research results under the title Ilios and his autobiography.

In 1882 his sixth excavation campaign began in Troy with the assistance of the young master builder Wilhelm Dörpfeld . In the same year he was appointed a foreign member of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences . In 1883 Schliemann was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of Oxford and an honorary member of Queen's College .

From March 17, 1884, he carried out very successful excavations in Tiryns together with Dörpfeld. Sixty workers removed the rubble from the Acropolis, where Cyclopean walls had already been discovered in 1876 , which now turned out to be the foundation walls of a Mycenaean royal palace with a large arcade courtyard , altar and frescoed rooms, bathroom and megaron . The discovery of the palace gave science a profound knowledge of the extent, heyday and fall of the Mycenaean era.

In 1886 Schliemann and Dörpfeld finished the excavations in Tiryns and went to Knossos on Crete , which was then still Ottoman , to buy excavation site and obtain an excavation license, but could not agree on a price with the landowner. In 1886/87 Schliemann, suffering from severe health problems, went to Egypt to first relax on a Nile cruise with his own yacht and from January 1888 to dig for Alexander's grave with Virchow at the Ramleh station in Alexandria . His project was supported by Johannes Schiess .

In 1889/90 Schliemann initiated and led two scholars' conferences in Troy. After the seventh campaign in Troy, Schliemann died - after an ear operation carried out in Halle / Germany that was not completely cured - on December 26th in Naples / Italy - from the consequences of a long-standing cholesteatoma . His body was transferred to Athens by friends and buried there in the magnificent neoclassical mausoleum designed by Ernst Ziller in the First Cemetery of Athens .

In his will, he paid particular attention to his children from his first marriage, who inherited his houses in Paris, and from his second marriage, who received property in Greece. But his living German relatives also received generous inheritance shares.

Excavations

Troy

Heinrich Schliemann was not the first to suspect the remains of the city of Troy (also Ilion, hence the name of Homer's epic Iliad ) under the hill called Hisarlık in Troas . The British traveler Edward Daniel Clarke came up with this idea at the beginning of the 19th century. In 1863 the journalist Charles McLaren published the same idea, which was then taken up by the British Frank Calvert . Calvert carried out the first excavations, but did not condense his hypothesis into an assertion. Schliemann wrote openly about what he owed Calvert: "... I fully share Calvert's conviction that the plateau of Hisarlık marks the site of ancient Troy".

In 1869/70, Schliemann verified Calvert's assumptions on the basis of the sometimes very exact description of the scenic location of the city by Homer and subsequent ancient writers, and carried out the first exploratory excavations . During the first three excavation campaigns (from 1871) Schliemann had his workers drive a 40 meter wide and over 15 meter deep trench through the middle of the hill in the hope, according to Ilion , to find Priam's castle . Important traces of settlement from all layers were irretrievably destroyed. In the following years and during excavations in other places, he therefore enlisted the help of a specialist ( Wilhelm Dörpfeld ) and went to work much more cautiously.

In 1873 Schliemann announced to the public that he had found Troy. The real breakthrough to fame, however, came with the discovery of the so-called treasure of Priam in the same year. In 1874 Brockhaus published Schliemann's “Atlas of Trojanischer Antiquities”, for the first time in the history of archeology, consistently with photo documents from the excavations.

There are convincing indications that armed conflicts have repeatedly been waged around this strategically and trade-politically significant settlement. Archaeological proof that Homer's Trojan War actually took place around this very settlement (this was Schliemann's core thesis) has not yet been provided - neither by him nor by his successors. Despite the lack of evidence, it is now undisputed among experts that the site excavated by Schliemann is actually Troy / Ilion. The excavations and research have been continued since 1988 by the Institute for Prehistory and Archeology of the Middle Ages at the University of Tübingen and the Department of Classics at the University of Cincinnati.

Schliemann was the first to discover a Bronze Age settlement outside of Egypt and Mesopotamia , thus opening up a completely new field of work for ancient studies.

Mycenae

Schliemann first visited the early historical ruined city of Mycenae in 1869. In contrast to others, he was looking for the burial place of Agamemnon (the legendary king and commander in chief of the Greek armed forces before Troy) not outside, but inside the castle walls. He started the excavations in 1876. The largest find was the so-called gold mask of Agamemnon from Mycenae, which, according to current knowledge, cannot, however, be attributed to Agamemnon, as it dates from an era around 300 years earlier.

Other archaeological sites

Schliemann also undertook extensive excavation campaigns in Orchomenos (treasure house of Minyas), Ithaka and Tiryns .

Appreciation

His carefree and thus initially unscientific approach to the first excavations in Hisarlık drew Schliemann a lot of criticism at the beginning. It was overlooked that he could not rely on role models. The fact that he fundamentally changed his methods made him (next to Flinders Petrie and especially Wilhelm Dörpfeld ) one of the pioneers of archeology as field work and the scientific-methodical excavation technique, which until then only consisted of the treasure-hunted excavation of valuable individual objects, but not the now systematic Uncovering an excavation area existed.

The following new research methods devised by him are still in use today: | October 11, 1990

- Preliminary investigation of the site by means of probes (search trenches);

- Excavation down to the natural ground;

- Observance of the stratigraphy (sequence of layers);

- Search for the lead ceramic (“lead fossil ”) for the individual layers;

- interdisciplinary collaboration with other sciences, including Anthropology, paleontology, paleography, topography and chemistry.

Through his numerous publications, he has decisively promoted public interest in serious archaeological research. His reports on the connections between Tiryns, Mycenae and Crete first brought these sites into the consciousness of historical scholarship. In professional circles, Schliemann is rightly recognized as the "father of Mycenaean archeology".

Rudolf Virchow said of him:

“Today it is an idle question whether Schliemann assumed correct or incorrect assumptions at the beginning of his investigations. It was not just success that decided in his favor, the method of his investigation has also proven itself. It may be that his assumptions were too bold, even arbitrary, that the enchanting picture of immortal poetry enticed his imagination too much, but this flaw of mind, if one may call it that, also contained the secret of his success. Who would have undertaken such great work, continued over many years, expended such enormous resources of his own possession, dug through an almost endless seeming row of piled-up rubble layers down to the primeval soil lying deeper than a man who was secure, even enthusiastic about one Conviction was permeated? Even today the burnt city would rest in the secrecy of the earth if the imagination had not guided the spade. "

Today the Heinrich Schliemann High Schools in Fürth and Berlin, the Heinrich Schliemann Neubukow Regional School and the Heinrich Schliemann Institute for Classical Studies at the University of Rostock bear the name Schliemanns. In Schwerin there has been a bust monument by Schliemann on Pfaffenteich since 1895, created by the sculptor Hugo Berwald , which was stolen at the end of August 2011. A bronze cast based on a plaster cast of the original bust has been in the same place since May 2012.

His parents' house in Ankershagen has housed the Heinrich Schliemann Museum since 1980 . Among other things, ceramic and bronze original finds and replicas from Mycenae and Troy are presented there. The Heinrich Schliemann Memorial in Neubukow has also been providing information about the city's most famous son since 1972 and exhibits original finds and replicas. The asteroid (3302) Schliemann and a moon crater on the back of the moon was named after Heinrich Schliemann.

In 1990 the Deutsche Bundespost and the Greek Post issued "ELTA" a special stamp as a joint issue on the occasion of Schliemann's 100th anniversary of his death. In the same year, the German Post of the GDR issued a special stamp with its own motif.

Works (selection)

Digital versions of numerous writings by Schliemann are available from the Heidelberg University Library (see web links).

-

La Chine et le Japon au temps present . Librairie centrale, Paris 1867

- Journey through China and Japan in 1865 . Translation into German, Konstanz 1984.

- Ithaca, the Peloponnese and Troy . Archaeological research, Giesecke & Devrient, Leipzig 1869, ( online - Internet Archive )

- Trojan antiquities. Report on the excavations in Troy. FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1874, ( digitized and full text in the German text archive )

- Mycenae . Report on my research and discoveries in Mycenae and Tiryns. FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1878, ( online - Internet Archive )

- Ilios . City and Country of the Trojans. Research and discoveries in the Troas and special at the construction site of Troy. FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1881 ( online - contains an extensive autobiography).

- Orchomenos . Report on my excavations in Orchomenos in Boeoti. FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1881 ( online - Internet Archive )

- Journey in the Troad . Leipzig 1881 ( online - Internet Archive )

- Troy . Leipzig 1883

- Tiryns . Leipzig 1886 ( online - Internet Archive ).

Film adaptations

- 1981: Priam's treasure - with Tilo Prückner as Schliemann.

- 2007: The mysterious treasure of Troy - with Heino Ferch as Schliemann.

literature

- Carl Schuchhardt : The excavations of Schliemann in Troja, Tiryns, Mykenä, Orchomenos and Ithaka . Brockhaus, Leipzig 1890. 2nd edition 1891 ( online ). Reprint: Leipzig 2000.

- Alfred Brueckner : Schliemann, Heinrich . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 55, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1910, pp. 171-184.

- Emil Ludwig : Schliemann. Story of a prospector . Introduction Arthur Evans . Zsolnay, Munich 1932.

- Ernst Meyer : Heinrich Schliemann. In: The ancient world . 16th volume, 1940.

- Heinrich Alexander Stoll : The Dream of Troy. Leipzig 1956; New edition: 2002, ISBN 3-356-00933-8 .

- Leo Deuel : Heinrich Schliemann. A biography. Hanser, Munich / Vienna 1979, ISBN 3-446-12730-5 .

- William M. Calder III , DA Traill (Ed.): Myth, Scandal and History. The Heinrich Schliemann Controversy and a First Edition of the Mycenaean Diary. Wayne State University Press, Detroit, 1st Edition 1986, ISBN 978-0814317952 .

- Wolfgang Richter : Heinrich Schliemann . Leipzig 1992, ISBN 3-379-00533-9 .

- Philipp Vandenberg : Priam's treasure - How Heinrich Schliemann invented his Troy . Gustav Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1995, ISBN 3-7857-0804-1 .

- Wilfried Boelke : Heinrich Schliemann. A famous Mecklenburg man. Demmler, Schwerin 1996, ISBN 3-910150-36-5 .

- Justus Cobet : Heinrich Schliemann. Archaeologist and adventurer. Beck, Munich 1997.

- Manfred Flügge : Heinrich Schliemann's way to Troy. The story of a mythomaniac . Deutscher Taschenbuch-Verlag, Munich 2001, ISBN 3-423-24292-2 .

- Wilfried Boelke, Reinhard Witte : Heinrich Schliemann Museum Ankershagen / Mecklenburg. Guide to the permanent exhibition . Ankershagen 2003 (with a detailed bibliography).

- Danae Coulmas : Schliemann and Sophia. A Lovestory. Piper, 2007, ISBN 3-492-23699-5 .

- Stefanie Samida : Heinrich Schliemann. Francke, Tübingen & Basel 2012, ISBN 978-3-8252-3650-2 (UTB Profile) review

- Irving Stone : The Greek Treasure. The life novel by Sophia and Heinrich Schliemann . Rowohlt, Reinbek 2004, ISBN 3-499-23533-1 .

- Justus Cobet : Schliemann, Heinrich. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 23, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-428-11204-3 , pp. 83-86 ( digitized version ).

- Reinhard Witte : Heinrich Schliemann. Looking for Troy . Frederking & Thaler, Munich 2013, ISBN 978-3-89405-992-7 .

- Stefanie Samida: The archaeological discovery as a media event. Heinrich Schliemann and his excavations in public discourse 1870-1890 , Waxmann, Münster 2018 (Edition Historische Kulturwissenschaften, Volume 3), ISBN 978-3-8309-3789-0 .

- Leoni Hellmayr: The man who invented Troy. The adventurous life of Heinrich Schliemann. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2021, ISBN 978-3-534-27349-2 .

- Frank Vorpahl: Schliemann and the gold of Troy. Myth and Reality . Galiani, Berlin 2021, ISBN 978-3-86971-245-1 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Heinrich Schliemann in the catalog of the German National Library

- Works by and about Heinrich Schliemann in the German Digital Library

- Works by Heinrich Schliemann in the Gutenberg-DE project

- Heinrich Schliemann in the Internet Archive

- Literature about Heinrich Schliemann in the state bibliography MV

-

Search for Heinrich Schliemann in the online catalog of the Berlin State Library - Prussian Cultural Heritage . Attention : The database has changed; please check result and

SBB=1set - Self-biography at zeno.org

- Digital copies of Schliemann's books ( memento from May 20, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) of the Heidelberg University Library

- The Heinrich Schliemann Museum Ankershagen is a center for international Schliemann research

- Theodor Kissel : archaeologist, visionary and influencer Spektrum.de , December 26, 2020

Individual evidence

- ^ Gustav Gamer : Frank Calvert, a forerunner of Schliemann. In: Ingrid Gamer-Wallert (Ed.): Troia - a bridge between Orient and Occident. Attempto, Tübingen 1992, ISBN 978-3-89308-150-9 , p. 42.

- ↑ http://www.lomonossow.de/2009_01/1_09_schliemannbild-heute.pdf

- ↑ His teacher was initially the businessman Ernst Ludwig Holtz, who died in December 1836, after which he learned from the brother of his daughter-in-law, Theodor Hückstädt (1812-1872), who continued the general store and later made a name for himself in the 1848 reform movement.

- ↑ Wilfried Bölke: Heinrich Schliemann. A famous Mecklenburg man. Demmler Verlag, Schwerin 1996, pp. 72–82 (with many more details on this period of life).

- ↑ More details: C. August Schröder: Heinrich Schliemann and the trading house Schröder , in: Verein für Hamburgische Geschichte (Ed.): Geschichts- und Heimatblätter 12th vol., 1992, p. 217ff. ( Digitized version . The businessman mentioned there and referred to as the “discoverer of Schliemann's genius” was Johann Heinrich Schröder (1815–1890) (Deutsches Geschlechtbuch 128, 10th Hamburg Volume, Starke, Limburg 1962, p. 167), not to be confused with the Johann Heinrich Schröder of the same name , with whom Schliemann was also connected).

- ↑ C. August Schröder: Heinrich Schliemann and the trading house Schröder , in: Geschichts- und Heimatblätter 12th vol., 1992, p. 220

- ↑ a b Prof. Dr. Joachim Mai: On the legal situation of Heinrich Schliemann in Russia from 1846 to 1864. In: Messages from the Heinrich Schliemann Museum Ankershagen. No. 5, 1997, pp. 57-62.

- ^ Justus Cobet : Heinrich Schliemann. Archaeologist and adventurer. Beck, Munich 1997, pp. 55f.

- ↑ German Archaeological Institute: Archäologischer Anzeiger 1 . 1889, p. 31 .

- ^ Wilfried Bölke: PhD at the Rostock University . In: Bölke 1996, pp. 160-168; Richter 1992, pp. 165-178.

- ^ Justus Cobet : Heinrich Schliemann. Archaeologist and adventurer. Beck, Munich 1997, p. 68.

- ↑ Carl Schuchhardt : Schliemann's excavations in Troja, Tiryns, Mykenae, Orchomenos, Ithaka in the light of today's science. FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1891, p. 9. ( online )

- ↑ inter alia: U. Erichson and W. Weitschat: Baltic amber. Ribnitz-Damgarten 2008

- ^ Gabriela Walde: Heinrich Schliemann and death in the "Grand Hotel" in Naples. January 19, 2016, accessed May 20, 2020 .

- ↑ Flügge 2001, p. 149

- ↑ Flügge 2001, p. 154 ff.

- ↑ Flügge 2001, p. 176

- ↑ Flügge 2001, p. 212 f., P. 220

- ^ Peter von Becker : Finale in the Grand Hotel. “Death in Naples”: The Neues Museum in Berlin commemorates the rise and end of the legendary magnate and archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann. In: Der Tagesspiegel , January 7, 2016, p. 20.

- ↑ Stefanie Samida : Heinrich Schliemann. UTB (= 3650), A. Francke, Tübingen 2012, ISBN 978-3-82523-650-2 , p. 54 f.

- ↑ Heinrich Schliemann Museum: Schliemann's lasting life's work ( Memento from September 12, 2010 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Rudolf Virchow: Preface. In: Heinrich Schliemann: Ilios, city and country of the Trojans. Brockhaus, Leipzig 1881, pp. IX – X ( online ).

- ↑ Schliemann the-moon.wikispaces.com, accessed 20 March 2012

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Schliemann, Heinrich |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Schliemann, Johann Ludwig Heinrich Julius (full name); Schliemann, Henry (anglicized form of name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German archaeologist |

| BIRTH DATE | January 6, 1822 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Neubukow |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 26, 1890 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Naples |